While Rod Hyde, Lowell Wood and John Nuckolls were working on laser-induced fusion to drive a starship back in 1972, the range of options for advanced propulsion continued to grow. One we haven’t talked about much in these pages is the use of gravitational slingshots in exotic settings. We’re used to the concept within the Solar System because spacecraft like Voyager and Galileo have used a ‘slingshot’ around a planet to alter course and accelerate. But interstellar visionaries like Freeman Dyson have looked further out to imagine other uses for such techniques.

In a 1963 paper, Dyson speculated on how an advanced civilization might use a binary star system made up of two white dwarfs. Send a spacecraft into the system for a close pass around one of the stars and, depending on the mass and orbital velocity of the stars, it is thrown out of the binary system at velocities as high as 3000 kilometers per second. But Dyson took the idea even further. His paper, which appeared as a chapter in a book called Interstellar Communication (New York: Benjamin Press, 1963), described not just white dwarfs but the creation of a binary neutron star system as an engineered launch platform.

I can’t, in a quick search of the office this morning, find my copy of this book, but David Darling has the numbers in his Encyclopedia of Science. Two neutron stars, each with a diameter of 20 kilometers and a mass of one solar mass — and a combined orbital period of 0.005 seconds — would provide a departure velocity of 0.27 c, which works out to 81,000 kilometers per second. The concept has worked its way into the literature as the ‘Dyson slingshot,’ an artifact produced by an advanced civilization for flinging things from star to star. See Gregory Benford’s The Stars in Shroud (1978) for possible uses of such a system.

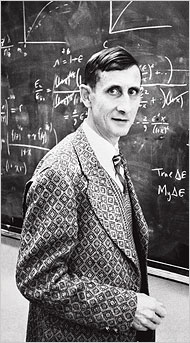

Image: Freeman Dyson pushed gravitational maneuvers to an extreme. Will future civilizations be able to manipulate neutron stars? Credit: New York Times

All this was in the air at a time when the very existence of neutron stars was in doubt (it would not be until five years later that Jocelyn Bell and Antony Hewish discovered the first radio pulsars, for which Hewish shared the Nobel Prize). Why get into all this in a book titled Interstellar Communication? Because Dyson also noted that a close binary system of neutron stars would decay in short order until the two components plunged into each other, creating a burst of gravitational waves that could be detected over millions of parsecs. Dyson thought it worth looking for events like this using some form of gravitational wave detection instrument.

But back to gravitational maneuvers to speed up spacecraft. Writing in the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society in 1972, German propulsion engineer Krafft Ehricke proposed using a gravitational slingshot to push a spacecraft out a tenth of a light year from the Sun. These days the plan would sound more familiar than it did when Ehricke wrote it: The probe would be sent first to Saturn for a propulsive maneuver as it moved behind the planet that would send it into a retrograde orbit, taking it near Jupiter for another slingshot toward the Sun.

Ehricke’s vehicle would close to within 1.6 million kilometers of the Sun, being flung around it and accelerated to 600 kilometers per second, which would take it to 6320 AU in 50 years. The engineer thought a mission like this could be useful as we learn about the interstellar medium and the outer system, but he believed 600 kilometers per second was about as much as he could wring out of the method. Actual interstellar missions would need breakthroughs of the kind Hyde, Wood and Nuckolls were examining at Lawrence Livermore, or perhaps antimatter.

I’m not clear on whether Ehricke was aware of the 1960s work of Robert Forward, George Marx (Roland Eötvös University, Hungary) and J.L. Redding (Bishop’s University, Quebec) on laser beaming to large space-based sails, but I haven’t yet found any reference to it in his work. He did, however, develop expansive ideas about our species’ role in the cosmos that I’ll be looking at shortly.

The Dyson paper is “Gravitational Machines,” in A.G.W. Cameron, ed., Interstellar Communication, New York: Benjamin Press, 1963, Chapter 12. Krafft Ehricke’s paper on gravitational assist is “Saturn-Jupiter Rebound: A Method of High-Speed Ejection from the Solar System,” JBIS 25:10 (October, 1972), p. 561.

Freeman Dyson is amazing… two years ago I emailed him with some thoughts and he responded almost immediately. He obviously doesn’t procrastinate, wish I could learn that lesson!

So Ehricke’s slingshot to get a telescope to the gravitational lensing position within 10 years or so? What sort of hardware could withstand such a close approach to the sun?

The idea seems feasible but implausible.

1. How would they obtain the neutron stars?

1.1 Traveling to them and towing them back would require some serious spacefaring technology

1.2 Creating them would require serious technologicy, period.

1.3 Where would they park the binary and how would they move it to that location?

Seems to me that a civilization that has the technology to accomplish any of this would already have solved the problems of interstellar travel.

A couple of issues here. One, high-velocity gravitational slingshots are great for launching but not for stopping at a destination. Unless of course the destination is also, say, a binary neutron. Second, to do better than the mentioned solar slingshot requires that one first reach a suitable binary star system. But if you can reach it you don’t need it.

So using Ehricke’s slingshoot idea as the First Stage what could you use for a Second Stage, would deploying a solar sail and beamed lasers provide even more velocity?

Extreme gravitational slingshot would work perfectly for a tiny robot probe, but what are the tidal forces for anything larger? Given that this neutron star propulsion would be so expensive to engineer, we would want to use it on very large ships, and how much spin would it impart to these? Would they need the power of a nuclear engine just to cancel this, and would it be easy to maintain the integrity of the hull?

Such problems must have already been worked out in detail, and I’m wondering if anyone here knows the answers offhand.

Dyson originally submitted the paper to the Gravity Research Foundation’s essay contest. A scan is available online at the GRF website. Dyson did note that a binary neutron star system had a very brief moment before it collapsed from loss of orbital energy via gravitational waves if it was orbitting so rapidly. Thus not a practical device. The white dwarf binary also would only last 40,000 years in the configuration needed to reach 2,700 km/s.

“-more than 100,000 KBOs over 100 km (62 mi) in diameter are believed to exist.[7]”

With Thorium reactors manufactured on the Moon and beam propulsion to start the journey, a gravity assist to the Kuiper belt and bomb propulsion to slow down upon arrival is probably the way to get out there and start colonies.

There is kind of a muddled history on Wikipedia about the history of gravity assists, seems the real physics was first done by the Russian Friedrich Zander in 1925.

It kind of kicked around in astronautics for years , but was famously proposed by Gary Flandro of JPL to do the Grand Tour for the Voyagers , after it was thought the Grand Tour was dead!

As to Dyson’s paper he does not give any references from astrodynamics papers or books, I think it had appeared in 1961 somewhere by Michael Minovitch. (Zander would have been hard to find.)

Never mind… it’s a good sophomore physics exercise in physics and would have been trivial for Dyson.

One thing to note, we have two known neutron star binaries PSR J0737-3039 and the famous PSR B1913+16 … thus there should be a number of neutron-neutron star binaries. We have even more black hole- black-hole binaries… one nearby , NGC 6240, those all these a galactic nucleus babes.

I don’t know of any cases of stellar mass black hole-black hole binaries, but there are a bunch of black hole – star binaries , the famous Cygnus X-1 being one. So probably stellar mass black hole – black hole binaries we have not seen yet.

It’s odd I thought I had a further paper by Dyson, or comment or something about using black hole – black hole binaries for gravity assist… but I can find it.

As is known to the really high speed assists… have worry about systems that don’t decay so fast by gravitational radiation they collide.

Not so handy for us, but other civilizations may be using them right now.

While photonic sail with laser beaming can accelerate, it wont help the breaking problem. Solar sail can do both. If we can use powerful lasers to beam energy and travel along these beam highways, and use captured interstellar atoms as fuel (accelerate them through engines) for ionic propulsion we might be able to both accelerate and decelerate.

The key points are

a) Do not carry fuel – get it along the way through beaming

b) Continuous steady acceleration and deceleration throughout the journey. Even 1g acceleration can take us to stars in our lifetimes. Pinpoint beaming across inter-stellar distances would be a hell of an engineering challenge. We might also need lasers of variable wavelengths to compensate for red shift

This slingshot idea is fundamentally flawed at least in the case of a single star and no use of a propulsion system at the point of closest approach.

For single sources of gravity, slingshots only work as a ‘free’ speed increase when the thing being slingshot from (eg. Saturn or Jupiter) is moving relative to your frame of reference – the incoming & outgoing speeds relative to it are the same but the speeds in your reference frame are not. Any star will be moving at an insignificant speed relative to the starting point (compared to 600 km/s) so the slingshot gains you neglegible speed.

Reason :

Conservation of energy implies that the spacecraft’s speed of motion relative to the star will (in the absence of a propulsion system or some other gravity well) be precisely equal before and after the slingshot, at the same distance from the star. Hence if it reaches “6320 AU in 50 years” then it would have reached “6320 AU in 50 years” (in some other direction) if just fired sent off from the same orbital radius in the direction opposite its starting direction.

Or put another way : it will lose the same speed travelling back away from the star, as what it gained on the way in.

The story will be more complicated for two stars or where you have a powerful propulsion system however (eg. rocket propulsion to accelerate in direction of travel at point of closest approach to the star gains you more speed when you go far from the star, than what you would have gained firing the propulsion at that place far from the star, but this is not a slingshot effect as such).

After a few more years we are going to want more data on the nearest star systems. We’ll have just enough to know that there are probable planets probably in this range or that range. So we may as well start sending the sling shot probes out now to begin the long journey to Epsilon Eridani, Barnard’s Star, Alpha Beta Centauri etc.. They won’t have to stop there, but rather just gather the essentials and send it back home to us. By the time we get the confirmations or not, we may be at a level to send colonial ships.

Has anyone considered using an actual giant slingshot located on, say, a planetoid? What kind of material could hold a large mass yet be flexible enough to be stretched and then released? How much velocity could we actually attain if this was used to launch a standard space probe say around the size of Cassini?

Yeah, yeah, you’ll be claiming you thought of it first when the numbers do work out.

@ljk Funnily enough I was thinking something very similar today. Suppose you have a long tether, with some sort of mechanism, e.g. rockets at each end. If the tether takes on a triangular shape, and the rockets “pull” the tether into a straight line, a projectile at the apex is accelerated to a velocity multiple of that of the rockets. I doubt this makes any practical sense, although definitely easier than creating close binary neutron stars. :)

Developing the drive system to travel interstellar distances is obviously the key element in interstellar travel, whether we “fly” there the hard way or “pop” there by means of some trick of physics. But which one? A propulsion system to fly there would be easier to design but the transit would take too long, while the “pop there” system would be a reasonable trip but to design it would take too long. And we could all grow old and die before we even decide which one to invest our time in. So in the meantime, why don’t we set a short term goal of getting a human-made object one light year from Earth by some technology that we have at or disposal today. Something that will produce concrete results in our lifetimes, and gravitational assist is it. I envision something like Voyager, except without the science stay-overs at planets yet with a lot more gravity assist from those planets to get out of the solar system ASAP. Then, once out of the solar system, that vehicle flings into interstellar space a series of small devices that are designed to do two things only, (1) go as fast as we can design them to go based on what we know now and (2) continuously transmit their position back to earth. If the launch system for these devices was well designed, maybe we could reach 5 percent light speed, which would get us out to one light year in, what, about 20 years? Then we can say we did it and learned what we had to do to get the travel time down. It could be a sub-project of 100YSS, “1ly” or “Onely” or “1ly project” or something.

I just had this great idea. Why not accelerate a probe with an actual slingshot? You can make it arbitrarily long, and it should the longer, the faster, no?

Well, I did the numbers, and guess what …. They don’t work out. Turns out, as the slingshot gets longer, it also gets heavier. Some simple math later, we get the maximum velocity gained from any sort of spring-like device as a small fraction of the square root of the elastic modulus divided by the density. Also known as the sound velocity, and for something as light and hard as diamond (or CNT), it comes out to about 12 km/s. Take a small fraction (the stretchability), end you end out with 0.5 km/s or so, at best.

Bummer, I would have so much enjoyed taking complete credit for this excellent idea of mine…. :-)

I wanted to add this great idea by Dr. Joseph Breeden to the mix, a proposal which seems a lot more practical than most of the ideas dealing with the use of gravitational slingshots for interstellar travel. Unfortunately, I have been unable to locate the original paper. Perhaps it will be published in the proceedings of the 100-Year-Starship conference.

“Participants at the event talked about a wide range of ideas, including how to prepare for and finance a century-long project like this. And though one may be wondering why such agencies are humoring such thoughts, perhaps Joseph Breeden, a physicist, puts it best, “The space program, any space program, needs a dream. If there are no dreamers, we’ll never get anywhere.” In fact, Dr. Breeden offered up the idea of an engineless starship.

Dr. Joseph Breeden’s Plan

Dr. Breeden remembered from his doctoral thesis that in a chaotic gravitational dance, stars are sometimes ejected at high speeds. He thinks that the same effect could work on starships. Dr. Breeden outlines the process as follows.

First, search for and locate an asteroid in an elliptical orbit that passes close to the Sun.

Second, put a starship in orbit around that asteroid.

If the asteroid could be captured into a new orbit that is close to the Sun, the starship would be hurled on an interstellar trajectory, maybe up to a tenth of the speed of light. “

Wile E. Coyote lied to us all….

Alex, you’ve effectively described a (large!) crossbow, albeit one with scaling issues for any known materials.

My apologies, Dr. Joseph Breeden and his wonderful idea was already noted in “The Joy of Extreme Possibility” by Paul Gilster on October 19, 2011. Oh my.

To my mind, Adam gives the key to how and under what circumstances a stage III supercivilisation would use a pair of close stellar mass objects, when he writes “Dyson did note that a binary neutron star system had a very brief moment before it collapsed from loss of orbital energy via gravitational waves if it was orbitting so rapidly”.

Surely the logical inference then is that an incredibly close pair of dense massive objects would only be used to decelerate trillions of tons of material from relativistic velocities each second, and deliver them into a very small (torus around the galactic core) just a few thousand AU width from the path of their COM. Why was anyone here even thinking of using it for acceleration when they knew that usage could not prevent collapse?

It seems to me that Dr. Joseph Breeden didn’t think his slingshot all the way through. If he had, ho probably would have had to go with Dyson and others before him that realized that it takes two heavy bodies to produce the effect by gravity alone. The sun and an asteroid would be no good. There just isn’t enough interaction between the asteroid and the ship. Unless you want to use a mechanical “bump”, an elastic collision of some sort. But in that case, we run into the same material limitation as with the cosmic crossbow, see above.

@Ron S. Yes it is the same mechanism as a bow, just replacing the spring of the bow with rockets. But we also don’t want to call momentum transfer with a tether a trebuchet either, do we? ;)

@Eniac If the probe and asteroid are tethered, you can get a good slingshot as the asteroid’s energy is transferred to the probe.

Eniac et al. “It seems to me that Dr. Joseph Breeden didn’t think his slingshot all the way through. If he had, he probably would have had to go with Dyson and others before him that realized that it takes two heavy bodies to produce the effect by gravity alone. ”

I’m at a disadvantage here because I haven’t read the paper. I’m unsure if anyone on this site has (if so, speak up!). Until that time I am thinking that Breeden has a fascinating idea (likely an application of the 3-body problem where the mass of the starship is negligible compared to the asteroid, and the mass of the asteroid is negligible compared to the sun); one that it we should be open to exploring. 3-body problems have a history of amazing and counter-intuitive solutions — because chaos is involved. So until someone catches Breeden with his decimal-points down, he strikes me as credible.

Let me add the following which may have bearing on Breeden’s idea and why I am unwilling to dismiss him out of hand. Donald G. Saari (Distinguished Professor of Economics and Mathematics) is a remarkable fellow who has done work with his students on the N-body problem, economics, and voting paradoxes. He explains his work in “The Power of Mathematical Thinking: From Newton’s Laws to Elections and the Economy,” (one of the courses offered by The Teaching Company.) If you are tempted to snicker at this time, don’t. This stuff is not trivial! Saari is a first-rate thinker and communicator. He and colleagues have examined aspects of the N-body problem yielding results that are astonishing. Moreover, all of his work is of that caliber and has bearing on interstellar exploration (did you even wonder how a society in a world ship is going to maintain its political stability? Election rules are part of the problem. So is economics.). So I am urging people to acquaint themselves with Saari’s work. It’s a true eye opener.

Note: I do not know if Saari and Breeden have any connection.

johnq:

I am not sure there even is a paper, my impression is it was more of an off-hand remark that got amplified in the press. I may well be wrong. In any case, my point was that the idea has been explored, by the likes of Dyson. It be far from me to suggest we should not be open to new ideas, just that we should first make sure they have not already been dealt with and (rightfully) dismissed in prior work.

Alex Tolley:

Sure, but only within the material-based restrictions of tethers, which are in the neighborhood of 2-5 km/s. The same “speed of sound” limit discussed above with respect to the slingshot or crossbow. You could, however, take advantage of the Oberth effect with tethers, same as with rocket propulsion.

@Eniac: In any case, my point was that the idea has been explored, by the likes of Dyson.

Really and truly? I guess you’re sure. I’m not. Link(s) please, but of course no one has seen Bardeen’s paper and that’s a problem, admittedly. Maybe it is forthcoming. I don’t know. I do know that one of the the biggest idea killers around is the line, “Oh, that is just like idea X, which was refuted by Dr. Y long ago.”

As for Dyson, I love and respect the man and his work, and he may well be the go-to guy for all your gravitational assist questions, but he is not the last word. So I’m sticking for now with my adamant position of wait-and-see.

johnq:

Yes, that and “Oh, this won’t work because of Z”. In this case, we have both, which makes this one of the deader ideas. Luckily, ideas are plentiful, like grains of sand. It is spotting the rare idea that might work what is most important. The others must and deserve to be killed.

The ability to sling shot around the Universe is engineering that is truly fascinating. A few comments went with, if you can use binary stars ‘no need’ to go to them. Considering ‘really big’ long-term projects… such as the milky way & Andromeda collison….you might want to use ‘the low end’ resources to ‘prep’ your Type III civilization for a multi-billion year real estate turn-over. If you had to organize a 100 million self-replicating probes, you might want to save on the energy budget by sending down a ‘slingshot pathway’ for positioning across the galaxy?