by Kelvin F.Long

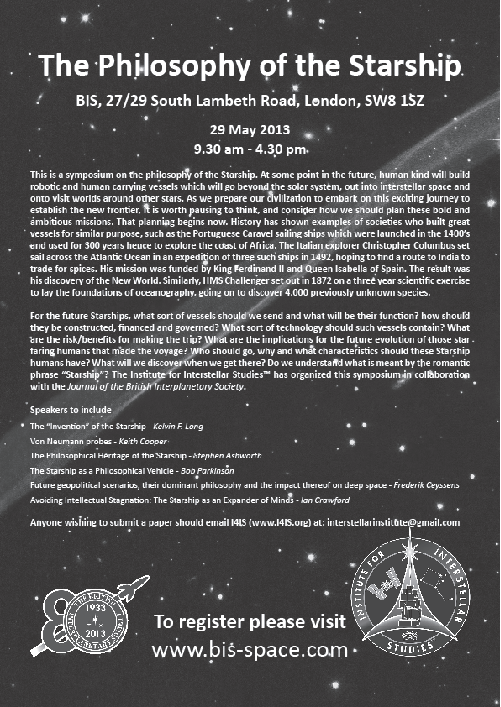

The executive director of the Institute for Interstellar Studies here gives us his thoughts on Star Trek and the designing of starships, with special reference to Enrico Fermi. Kelvin is also Chief Editor for the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society, whose latest conference is coming up. You’ll find a poster for the Philosophy of the Starship conference at the end of this post.

Like many, I have been inspired and thrilled by the stories of Star Trek. The creation of Gene Roddenberry was a wonderful contribution to our society and culture. I recently came across an old book in the shop window of a store and purchased it straight away. The book was titled The Making of Star Trek, The book on how to write for TV!, by Stephen E.Whitfield and Gene Roddenberry. It was published by Ballantine books in 1968 – the same year that the Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C Clarke 2001: A Space Odyssey came out. What with all this and Project Apollo happening, the late 1960s was a time to have witnessed history. Pity I wasn’t born until the early 1970s when the lunar program was winding down. I digress…

In this book, one finds the story of how Roddenberry tried to market his idea for a new type of television science fiction show. It is clear from reading it that Roddenberry was very much concerned for humankind and in the spirit of Clarke’s positive optimism, he was trying to steer us down a different path. In this book we find out many wonderful things about the origins of Star Trek, including that the U.S.S Enterprise was originally called the U.S.S Yorktown and that Captain James T.Kirk was originally Captain Robert T. April. He was described as being “mid-thirties, an unusually strong and colourful personality, the commander of the cruiser”.

The time period that Star Trek was said to be set was sometime between 1995 and 2995, close enough to our times for our continuing cast to be people like us, but far enough into the future for galaxy travel to be fully established. The Starship specifications were given as cruiser class, gross mass 190,000 tons, crew department 203 persons, propulsion drive space warp, range 18 years at light-year velocity, registry Earth United Spaceship. The nature of the mission was galactic exploration and investigation and the mission duration was around 5 years. Reading these words today, we see that what Roddenberry was doing was laying the foundations for many future visions of what starships would be like.

To Craft a Starship

What I found absolutely fascinating about reading this book however, was the process by which Roddenberry and team actually came up with the U.S.S Enterprise design. Roddenberry met with the art department and in the summer of 1964 the design of the starship was finalised. The art directors included Pato Guzman and Matt Jefferies. Roddenberry’s instructions to the team on how to design the U.S.S Enterprise were clear:

“We’re a hundred and fifty or maybe two hundred years from now. Out in deep space, on the equivalent of a cruise-size spaceship. We don’t know what the motive power is, but I don’t want to see any trails or fire. No streaks of smoke, no jet intakes, rocket exhaust, or anything like that. We’re not going to Mars, or any of that sort of limited thing. It will be like a deep-space exploration vessel, operating throughout our galaxy. We’ll be going to stars and planets that nobody has named yet”. He then got up and, as he started for the door, turned and said, “I don’t care how you do it, but make it look like it’s got power”.

According to Jefferies, the Enterprise design was arrived at by a process of elimination and the design even involved the sales department, production office and Harvey Lynn from the Rand Corporation. The various iterations produced many sheets of drawings – I wonder what happened to those treasures? The book shows some of the earlier concepts the team came up with.

Today, many in the general public take interstellar travel for granted, because Star Trek makes it look so easy with its warp drives and antimatter powered reactions. But for those of us who try to compute the problem of real starship design, we know the truth – that it is in fact extremely difficult. Whether you are sending a probe via fusion propulsion, laser driven sails or other means, the velocities, powers, energies are unreasonably high from the standpoint of today’s technology. But it is the dream of travelling to other stars through programs like Star Trek that keeps our candles burning late into the night as we calculate away at the problems. In time, I am sure we will prevail.

Fermi’s Enterprise?

There is an element of developing warp drive theory however that is usually neglected and I think it is now time to raise it – the implications to the Fermi Paradox. This is the calculation performed by the Italian physicist Enrico Fermi around 1950 that given the number of stars in the galaxy, their average distance, spectral type, age and how long it takes for a civilization to grow – intelligent extraterrestrials should be here by now, yet we don’t see any. Over the years there have been many proposed solutions to the Fermi paradox. In 2002 Stephen Webb published a collection of them in his book If the Universe is Teeming with Aliens…Where is Everybody? Fifty Solutions to the Fermi Paradox and the Problem of Extraterrestrial Life, published by Paxis.

One of the ways to address this is to ask if interstellar travel was even feasible in theory, and as discussed in my recent Centauri Dreams post on the British Interplanetary Society, Project Daedalus proved that it was. If you can design on paper a machine like Daedalus at the outset of the space age, what could you do in two or three centuries from now?

But even then travel times across the galaxy would be quite slow. The average distance between stars is around 5 light years, the Milky Way is 1,000 light years thick and 100,000 light years in diameter. Travelling at around ten percent of the speed of light the transit times for these distances would be 50 years, 10,000 years and 1 million years respectively. These are still quite long journeys and the probability of encountering another intelligent species from one of the 100-400 billion stars in our galaxy may be low. But what if you have a warp drive?

The warp drive would permit arbitrarily large multiple equivalents of the speed of light to be surpassed, so that you could reach distances in the galaxy fairly quickly. Just like Project Daedalus had to address whether interstellar travel was feasible as an attack on the Fermi Paradox problem, so the warp drive is yet another question – are arbitrarily large speeds possible, exceeding even the speed of light?

If so, then our neighbourhood should be crowded by alien equivalents of the first Vulcan mission that landed on Earth in the Star Trek universe. To my mind, if we can show in the laboratory that warp drive is feasible in theory as a proof of principle, and yet we don’t discover intelligent species outside of the Earth’s biosphere, then of the many solutions to the Fermi paradox, perhaps there are only two remaining. The first would be some variation on the Zoo hypothesis, and the second is that we are indeed alone on this pale blue dot called Earth. Take your pick what sort of a Universe you would rather exist in.

As to the point that life extension and “uploading” will make us more patient to travel long distances: I seriously doubt that. Our day to day impatience and demand for instant gratification has very little to do with the fact that we may die in a few decades. Our (lack of) patience is related much more to the speed of thought than length of life. Uploading, for one, is going to work in the opposite direction, making thought faster and individuals less patient…

Of course I agree with A.A. Jackson that we cannot predict our future. There are certain things though, that we can know about the future. The laws of physics as we know them seem pretty safe, at this point. The persistence of life is another pretty safe bet. The possibility of interstellar travel is another, that we mostly agree on. When talking about the future, the important thing to realize is that the only thing amenable to prediction is principles, never specifics.

One such specific prediction “it’s going take a long long time before the economics for even robotic stellar flight are possible.”, for example, may turn out entirely wrong in just a half century, depending on how things develop in automated manufacturing and robotics. The energy and resource are out there. If the machines that harvest them can build themselves, star flight can be as cheap as we want to make it. The very concept of “economic limits” may be overthrown completely.

Perhaps, but maybe that’s because we’ve paid so much attention to recreating the Enterprise’s propulsion, phasers, tricorders, etc. that we’ve forgotten to recreate Roddenberry’s vision of a pluralistic 23rd century society. We need to get social scientists as involved in space exploration as the physical scientists otherwise the best laid plans of physicists and engineers will fall apart because of humans’ inabilities to tolerate each other.

I would think that opening up the space frontier so that everyone can go their separate directions is the solution to peoples’ inabilities to tolerate each other. No social engineering necessary.

What say you?

Ok I go to reformulate my Argument: there is a possibility of warp drive be possible and Alien species already capable of interstellar travel visit us,but don’t care for us, beyond study us,because in space they have enough natural resources,and everything to survive without conquest here, they don’t need nothing from this solar system so they come here just for study,nothing else like made a official contact with a specie that are not capable of interstellar travel like the Humankind

It’s similar to the Vulcan on star trek before humans reach the warp drive they don’t care for us humans

That is what I think that could happen right now is a possibility

The Fermi paradox is based on the assumption that an ETI that could travel the stars would go everywhere. I don’t see any reason to assume they would, why bother?

It is possible that there is ETI who can travel about our galaxy, but don’t contact us because we are not interesting. After all what have we done? Just sent twelve people to our own moon and sent out a few simple probes that have not even left our solar system. It might make more sense to wonder why no ETI’s are visiting if we had done something to look interesting to them.

We need to make more of an effort ourselves.

railmeat:

Easy question. We can safely assume they procreate. We may also assume that some of them will want to go where no-one has gone before. A few million years of that, and such places will run short even in the largest of galaxies. As a consequence, they are everywhere, whether they wanted it or not.

I’m surprised that no one has said this yet, but surely the purpose of the Enterprise, its design, and so forth are pretty much direct steals from “Forbidden Planet”? That used a flying saucer (the Enterprise is a flying saucer with rockets), travelled by “time warp”, had the vessel revisit a forgotten colony on a world once inhabited by a now extinct civilisation. (That was also an adaptation of Shakespeare’s “The Tempest”, which Trek also did. And for all the “new worlds” stuff, they found a world with Zephram Cochrane (so not new to someone), a world where Brahms (who’d also been half the DWEM geniuses) lived: “Requiem for Methuselah”) and so on. In fact, wherever they went, the Enterprise kept finding white people who spoke English.

See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Forbidden_Planet#Plot The ship is a cruiser; it travels 16 light-years (hence range 18, anyone?). “Leslie Nielsen as Commander John J. Adams” note middle initial. There’s a droll ship’s doctor, and the captain gets the one (leggy) female. Only thing missing: he doesn’t get beaten up by a Gorn.

What does Trek add to this? Really, not a lot.

That’s not to say that Roddenberry hadn’t started something: “Devil in the Dark” was mentioned above, and that was classic Trek where they find a solution better than shooting the bad thing.

Brett Bellmore: “And it’s not just all our eggs in one basket, it’s all the galaxy’s eggs. We owe it to the universe to spread out, so that intelligent life will not perish when the next extinction event happens on Earth, as it inevitably will.”

This is probably the best and most important point anyone has made and anyone can make. This should be like a new gospel, a mission for humankind. I wish we had more visionaries, who would concern themselves about these long-term issues rather than the delusions of the moment.

railmeat: further to Eniac’s good argument, I strongly disagree with you for another reason;

no matter what we humand have achieved in terms of space faring capability, we are indisputably an advanced intelligence and a technological civilization, and we may even be expected to be able to reach interstellar capability within a few centuries or a millennium, a blink of an eye in cosmic terms.

Furthermore, our planet is full of complex life, which is probably rather rare in the galaxy anyway.

More than sufficient reason for any advanced civilization to want to study us and keep us under close surveillance.

I am fully convinced that, if any advanced civilization, capable of interstellar travel, exists in our galaxy, they will be highly, highly interested in us.

Railmeat wrote “The Fermi paradox is based on the assumption that an ETI that could travel the stars would go everywhere. I don’t see any reason to assume they would, why bother?”

And though Eniac has already shown the obvious problem with that, I found it of great interest that, in a previous discussion, A.A. Jackson attempted to bolster the above argument by pointing out how poor our knowledge is is of the “phase space” of ETI mindsets. But what really interested my was what that implied…

Someone of Jackson’s background making a serious suggestion that imbedded the concept that (with respect to parameters that determine expansion) ETI that are star-travel capable show far less diversity than the pre-starship civilisations within our one species. There might be no tail to that curve that is sufficient to allow a tiny fraction of them to expand. How can that be explained?

I have thought long and hard about it, and the plainest solution is that Vinge’s singularity is INEVITABLE BEFORE startravel, and this synchronises ETI outlook in some mysterious. Of, there are other far more complex solution if we ignore the penultimate clarifying sentence placed in the last paragraph. Unfortunately they all look to require significant fine tuning of that phase space.

“-they will be highly, highly interested in us.”

I am sure they will have a book on how to prepare Man.

Danangel said on May 4, 2013 at 21:11:

“Gary Church, I read the entire Hornblower series in the 5th grade and wanted more. C.S. Forester led me to feel the ocean spray on my face and the salt breeze in my hair. I’ve read them all again and more than once, but found that they are not available in the public or school libraries these days. Sad, really.”

My local Barnes & Noble has two – two – entire bookcases devoted to the subject of… Teenage Paranormal Romance.

I believe we may now be able to pinpoint the precise location and date of the decline of human civilization.

railmeat said on May 5, 2013 at 14:34:

“It is possible that there is ETI who can travel about our galaxy, but don’t contact us because we are not interesting. After all what have we done? Just sent twelve people to our own moon and sent out a few simple probes that have not even left our solar system. It might make more sense to wonder why no ETI’s are visiting if we had done something to look interesting to them.”

Ya gotta start somewhere. It would be far worse if we never even accomplished this much, though note how after our initial burst of intense space exploration we have sent no humans to the Moon since 1972 and only one probe on an interstellar course (only as a by-product of its main mission) since the Pioneer and Voyager probes in the 1970s. Everything else is on the proverbial drawing boards, if that, and NASA recently said they had no intention of manned lunar expeditions for the forseeable future.

Another reason advanced ETI may not know about us: Our various electromagnetic transmissions from Earth make a sphere roughly 200 light years in diameter, which is rather small compared to the 100,000 light year wide Milky Way galaxy.

This diagram will give you some idea how small our cosmic “footprint” is:

http://www.geekosystem.com/human-radio-broadcasts/

Yes advanced ETI with really big space telescopes could detect our radio noises, at least the stronger ones like military radar beams, or observe our planet well enough to see continents and perhaps more, but when you have 400 billion star systems to scan, that could take some time even for the really advanced species. And one should assume there are things much closer and more interesting for them to investigate first.

Tying in Star Trek and the theme of who would or would not conduct interstellar travel, the Star Trek: The Next Generation episode “The Nth Degree”, which introduced the Cytherians. A very advanced species living near the center of the Milky Way galaxy, they explore space by sending out probes that “adjust” (enhance) other species so they can travel to the Cytherian home world. They ended up doing this to Lt. Barclay, whose heightened intelligence creates a way for the Enterprise to travel faster than warp speed to the Cytherians. There the two species spend ten days exchanging information before the Federation starship is sent home.

http://en.memory-alpha.org/wiki/The_Nth_Degree

Two things to note: The Cytherian probe originally tried to uplift both a giant space radio telescope called the Argus Array and a Federation shuttlecraft, assuming both were intelligent species, even though the brief view we have of an actual Cytherian looks awfully humanoid (or maybe they project a relatable image to the species they have “invited” to their world).

I would also think that involuntarily enhancing and transporting an alien species to their home world could be a rather dangerous thing to do for the Cytherians, though it is easy to get the impression they could handle most threats.

Still, the Enterprise crew was pretty much less than thrilled with the situation as Barclay mysteriously got smarter and reengineered the Enterprise for its journey, which the starship crew was unable to stop. I can image other less enlightened species being even less happy with such a situation regardless of the Cytherians’ peaceful intentions.

In any event, it is a different way to explore deep space and perhaps an alien species might do some kind of variation of this. We can argue the points of how dangerous it might be and how this is basically kidnapping, but an alien mind and culture is an unpredictable thing at present, especially if one species views others as unequals.

This reasoning only applies to those advanced ETI that remain stuck in or near a single home system for REALLY long periods of time. I have the feeling that there may not be many of those.

@Dave Weeden

Forbidden Planet is a odd bird.

No film had ever done canonical prose science fiction Space Opera until 1956.

(I mean Space Opera in the sense that John Campbell, he had put a hard stop on BEMs and Brass Bras -Flash Gordon-and-Buck Rogers stuff in 1938.)

He discovered Robert Heinlein, Issac Asimov , A.C. Clarke, and a treasure trove of dozens of other writers who had, really on their own, discarded pulpy SF of the 20’s and 30’s. Prose SF became more sophisticated space opera , explorations of other ideas were in favor by Campbell, as long as the story telling was good. The beginnings of Hard Science Fiction.

On the page SF prose form it has never gone back to Gernsback days.

William Shakespeare’s “The Tempest” is there mainly as a vainer, the basic underpinning of the plot is good ol prose SF , really from the 1940’s. The Krell and the Super Science are due to Campbell’s boys. The story is by two writers Irving Block and Allen Adler. Both interested in modern SF prose.

I don’t have the reference at my finger tips but my understanding is that it was Irving Block who was the SF prose reader and basic underlying super science , warp drives to ‘the knowledge of the Krell’ were from him. Cyril Hume wrote the screenplay , I have the suspicion he was an SF reader too, he must have agreed with Block and Adler.

I can tell you an odd thing, MGM produced some promotion spots , aired on TV in 1956 before the movie opened, the content of which was “MGM has made a good science fiction film for release this summer”. I don’t know what other people thought but us SF fans had an inkling from the production clips and stills.

And so it was, its kind of a quasi-big-thinks* SF film, the Krell and all.

Some awkward cliche’s , but a good cast, Walter Pidgeon (a very respected actor ), Anne Francis seems dressing, but she’s ok in the film, Leslie Nielsen (way way long before he did comic stuff) and the respected Warren Stevens.

As a film , for the late 50’s it is an anomaly. VFX work by Disney generally worked, but this was long long before digital stuff.

Dr. Morbius’s tour of the abandoned Krell underground city is still a stunner.

To correct something, yes Star Trek didn’t do anything exactly new from Forbidden Planet , but it was Space Opera brought to TV (it was not the first good TV SF, OUT THERE and the better known TALES OF TOMORROW, were that, but they did more than Space Opera). Once again space opera borrowing from prose SF.

In fact after Forbidden Planet Hollywood did not touch space opera for another 21 years! with Star Wars.

The only step that Hollywood could take in the Space Opera direction would be to go super sophisticated and do Poul Anderson’s Technic History, especially the Dominic Flandry stories. A giant step beyond Star Trek and Star Wars … but I don’t think we will ever see it.

*We did not get a BIG THINKS SF film till 2001.

I have never heard what Kubrick thought of Forbidden Planet.

Boy, let me say in advance that I’m sorry to come back to what is surely a minor point (and I’m hoping not to get myself banned here.)

I think the disconnect is that, in the original post, the author really meant to say something like “the average distance from any star in this galaxy to its nearest neighboring star is about 5 light years” but I instead took him at face value when he said “The average distance between stars is around 5 light years”. (Later in the comments he added a “in the Milky Way galaxy” to this.) If that were really true, then the number of stars within a 5 ly radius of an ‘average star’, times the difference between each of their distances from that star and 5 ly, absolute value of those, summed, would have to be on the order of the sum of the differences of distances of all those stars which are over 5 ly away, from 5 ly, abs val, summed. That can’t be possible (unless maybe if you had a really really small galaxy?)

The number of stars that are farther than 5 ly away from an ‘average’ star, I submit, is vastly vastly greater than the number of stars that are less than 5 ly away.

You get what I’m saying, right? I’m very happy to be corrected, if I’m thinking wrongly about this issue.

Chris: both astronomically and mathematically you are, of course, right.

However, this is merely a matter of semantics. What the author, again of course, meant to say is that (in our MW galaxy) the average distance between two *neighboring stars*, or the average distance from any star to its nearest neighbor star is about 5 ly.

I think this is about right, at least in the galactic disk. The average stellar density there is about 0.002 per cubic ly, or about 1 star per 500 cubic ly. This works out as a bit less than 5 ly between each two neighboring stars, on average. Including the galactic core the density is a bit higher and average distance may go down a bit, maybe to 3 ly or so. I don’t know about the galactic halo.

But overall, for most of the galactic disk, including our own corner, this estimate looks about right.

The last paragraph of the article really sums it up…

The Fermi Paradox is a HUGE problem.

The only ways for it to not be a huge problem would be for humans to be the only ones around, or that space travel in general turns out to be basically unfeasible in interstellar terms.

Either alternative does not bode well.

Hopefully, there is some angle or answer or direction that no one has thought of yet. Fermi was the smartest guy on the block, and if he calculated that “Houston, we have a problem”, we really have one.

When I first read about the universe as a simulation theory, I discounted it. But with things like the speed of light being only observed and not derived, and there being no signs of life “out there” when it should be bustling with travelers, I have to pause and go, hmmmm.

Paul W:

The speed of light is not a “real” number, it is just a meaningless conversion factor between time and distance units. Strictly speaking, then, it is indeed derived. There are very few real (i.e. dimensionless) numbers out there, a famous example being the fine-structure constant. This dearth of variables in our cosmological model is the crowning achievement of theoretical physics, an incredible advance from the days of the periodic table and the associated zoo of unexplained facts and numbers before the advent of the Standard Model.

I am not sure where you are getting the “should” from. There is nothing ordinary about life. Even the simplest imaginable organism capable of autonomous self-reproduction is incredibly complex. The genesis of the first such organism is shrouded in mystery, and there are not many clues about how likely it is to occur spontaneously. The Fermi question is the strongest evidence, and we all know which way that points. To me, rare life is the default assumption, anyway, because of the obvious immense gap between non-living and living.

Eniac wrote: “One such specific prediction “it’s going take a long long time before the economics for even robotic stellar flight are possible.”, for example, may turn out entirely wrong in just a half century, depending on how things develop in automated manufacturing and robotics. The energy and resource are out there. If the machines that harvest them can build themselves, star flight can be as cheap as we want to make it. The very concept of “economic limits” may be overthrown completely.”

Thanks for this. Interesting claim. I am one of those who you are criticising. Yes indeed, the energy is out there. I think with me it’s a case of once bitten, twice shy: it was once promised that nuclear energy for civil power supply would be too cheap to meter, yet in practice it’s no cheaper than fossil fuels. Like Athena Andreadis and Calvin Johnson, I detect a slowing down in the rate of technological innovation: we are not on an exponential curve leading to a technological singularity, but a logistic curve leading to a technological plateau.

So you could be right, but you could be wrong: it’s perfectly possible that the self-assembling robots will suffer from drawbacks that make them only a small improvement over current methods of energy production and infrastructure assembly. Some of them, for example, might turn into predators that attack the others (hardware incarnations of present-day computer viruses), leading to costly defensive systems. For the present, I prefer to project the future based on what appears feasible today, rather than on “magical” (Arthur C. Clarke’s sense) things which would transform society but may or may not be possible in practice. The same goes for the science fictional warp drive as well, of course.

Stephen

Oxford, UK

Eniac, totally agree with you about the immense gap between non-living and living, and the key point that we have no knowledge about the genesis of the first living organism. This undermines one side of the Fermi “paradox”, making it no paradox, but simply an unanswered question.

However, your point: “Even the simplest imaginable organism capable of autonomous self-reproduction is incredibly complex.” does suggest that your self-assembling robot factories may not be very easy to develop…

Stephen

Astronist:

Good observation. Consider, though, that the machines we build today are also incredibly complex, and many already surpass some of the simpler autonomous microbes in complexity.

Depends, of course, on how you define complexity. Number of distinct parts seems like a good first crack at it. Simple, yet autonomous microbes work with just a few thousand different molecules (most of them proteins). A typical automobile has about 30,000 parts (roughly the number of human genes), and “The most complex machine ever built, the space shuttle has more than 2.5 million parts” (http://wiki.answers.com/Q/How_many_Parts_in_a_space_shuttle)

So, since a decade or two, the only thing we are lacking is the right design, and I think that will not take longer to come up with than a few more decades. After all, we know that it is possible. Von Neumann reasoned it, and those microbes are showing us.

I don’t think so. It is considerable cheaper. Or rather, its cost is low, with the price inflated by a gigantic profit margin. The companies operating reactors love them and can’t get enough. The reason the energy is not sold for cheaper is that the supply of reactor capacity has been severely restricted since the seventies, for various reasons, not many of them rational.

Eniac, I have never seen the current cost of nuclear power generation put at the levels you posit, however the following interests me.

If paranoia over nuclear waste disposal abates, and we replace it instead with the criterion that on average a similar amount of radioactivity per joule is allowed to leak into the environment as per coal powered generation, then how low would its new cost of generation be?

If we compare the Star Trek universe with current TV SF offerings or even going back 10 years- there is nothing being offered about space travel per se. This year’s most interesting TV offering is “Orphan Black” essentially about cloning. On the big screen, the one stand out space travel movie “Prometheus ” the protagonist are threatened by all the ET’s that they encounter plus the malevolent head of the multinational(interplanetary?) corporation that runs the project. private enterprise has never fared very well in its portrayal within the TV/movie SF presentations.

DARPA may or may not be truly interested in interstellar space travel, but there is a strong possibility that a newer more diverse audience as well as a newer more diverse set of minds may come up with some interesting technological innovations whose consequences/benefits are yet to be seen. I believe that DARPA provided some initial funding to the cloaking device research which is on the cusp of reality albeit a militarized reality.

As for TV SF offerings, there are the few episodes of “Defying Gravity” with a remarkably realistic looking spaceship on a mission around the Solar system. Unfortunately it seems a lack of viewers canned it as a series.