We become so bedazzled by the assumptions of our time that we can forget how things looked in different eras. 1973 wasn’t all that many years ago in the cosmic scheme of things, but the early ’70s were a time of surprising optimism when it came to our future in space. As we saw yesterday, physicist Robert Forward laid out a plan for interstellar expansion to a subcommittee of the U.S. House of Representatives in 1975, even as a thoughtful Michael Michaud worked out his own concepts in a series of papers in the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. But nudging ahead of both men by a few years was G. Harry Stine.

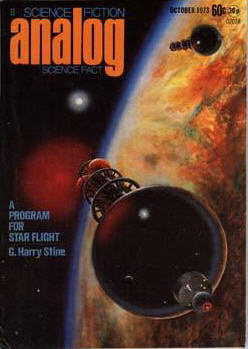

Already making a name for himself as a science fiction writer under the pseudonym Lee Correy, Stine was a futuristic thinker who fired readers’ imaginations with a cover article in the October, 1973 Analog, an issue whose artwork I reproduce here. Rick Sternbach’s cover caught my eye when I first saw this issue while toiling as a grad student that year, but it was the Stine article, “A Program for Star Flight,” that made me move the magazine to the top of my ‘must read’ list, even though I had little time for reading outside my class work.

Stine wanted to examine starflight by starting with “what we know now or with things that are amenable to engineering development.” This is Bob Forward’s spirit being channeled by Harry Stine, a look for solutions within known physics that pushed engineering as hard as it could be pushed, assuming that future developments would allow the production of the huge amounts of energy demanded. Stine didn’t want to pick up science fiction tropes he considered over the top, like faster-than-light travel or cryo-preservation. He thought in terms of huge ships and trips that lasted for generations.

In most respects, we’re still in the Stine era, in the sense that while we’ve learned a great deal about the stars around us and have made huge advances in computer technology, our basic methods of reaching space — chemical rocketry — are still in place despite the intervening 40 years. Project Icarus exists partly to look at what changes have occurred in this period to make starflight a more practical proposition, but it’s a daunting fact that we’re still trying to light fusion in a sustainable and productive way and we certainly don’t have it yet for propulsion.

Image: Rick Sternbach’s cover art depicting an Enzmann starship, as discussed in Harry Stine’s article.

But it’s interesting to look at Stine in another way. For in this article he lays out a basic justification for going to the stars that emerged at a time when the Apollo program had triggered serious blowback from those who wanted all our resources to be applied to Earth’s problems first. So let’s look at Stine’s list and see how his own rationale for starflight stands up from our vantage point today. I’ll go through all eight of his points in the order presented.

- Species survival. Stine worried about two things, the most likely being that through our own actions, we might destroy our ecosystem and have to find a new home. The other possibility was that the Sun might show signs of becoming unstable. Today we’d relegate that latter point to a distant future, one far enough out (at least a billion years) that it wouldn’t demand action in the near future. And more than solar instability, we’d be worried about the Sun simply playing out its normal life sequence, warming and eventually swelling into a red giant rather than going nova. On the question of planetary protection from space debris as a motivator for deep space technologies, Stine has no comment.

- Information. Just before the dawn of the personal computer revolution, Stine believed that information was the key to survival, and that the more of it we had, the better able we would be to thrive as a culture. I tend to think in terms of information being its own reward, with the quest for knowledge being simply hard-wired into our species, but Stine was a more hard-headed individual who saw accumulating data as an insurance policy against future catastrophe.

- Life search. Stine’s view was that our exploration of the Solar System might reveal life, and that this would be a driver for making us want to search around other stars. Conversely, finding no life might equally become a driver as we looked for further evidence that we were or were not alone. Today we still have no proof of life elsewhere in the Solar System, but we certainly have more targets than Stine did — beyond Mars, we’re looking at Enceladus, Titan, Europa, and even distant Triton, among other possibilities — and a growing understanding that life may be able to emerge in conditions that in Stine’s day would have seemed impossible.

- Intelligence search. Still no confirmed signal from SETI, and I suspect that Stine would have thought one was likely by now. But he opines that it may take going out to the stars and looking to discover whether or now other civilizations exist. Remember, too, that his was a time without the proliferating population of exoplanets we’re finding with our new tools and techniques, one in which there was still some thought that sending a probe was the only way to observe the planets around other stars. Today we’re expanding SETI to include searches for large-scale engineering (Dyson spheres and more) and each day seems to bring a new exoplanet discovery.

- Lebensraum. Here it’s hard to say whether Stine sees a crowded and choked Earth getting population relief from starflight — an unlikely scenario — or whether he means that future colonists will have all the room they could imagine for future growth. The latter is obviously true and we can envision substantial settlements moving into the outer system and beyond, but my assumption is that problems of overcrowding on Earth will demand Earth-based solutions.

- Sociological research. I like this one because Stine is envisioning generation ships with thousands of inhabitants and the ‘laboratories’ of social change they will provide. The point is well-taken, for long before we think about human colonists to the stars we may be looking at large space colonies in artificial habitats. The more of these that appear the greater the spread of human interactions in settings that will become isolated as they move further from the Sun.

- Ideological reasons. Harking back to the settlement of New England, Stine notes that people are willing to endure hardships to support their various ideologies. Viable colonies in space and, eventually, generation ship possibilities will become a powerful inducement for people to follow their own notions and establish communities that exemplify them.

- Economics. Here I can imagine several researchers I know who’ve looked hard at the cost of interstellar travel choking — aren’t we talking about trillions of dollars at this point to send spacecraft to the stars? Well, there are somewhat cheaper alternatives, and of course we’re looking for technology advances that can lower the astonishing cost of the energy we’ll need. But when Stine wrote, the profit motive keyed off the history of exploration on our planet and seemed a rational possibility. Today we’d say that turning a profit on an interstellar voyage is perhaps the least likely reason for constructing a starship.

Here’s Stine’s take on the eight items:

These are general reasons, and I won’t attempt to assign priorities to them or even try to guess which one, if any, will be the final justification used. I refuse to do this because I have a built-in cultural bias. I am an American who speaks and thinks in the English language and who has an Anglo-Hellenic cultural heritage. Star flight may be accomplished by another culture for reasons that would seem absurd to Americans. In other words, don’t assume that star flight won’t be done because we have lost our nerve, drive, or ambition — because you are speaking strictly of our culture. When it comes time to go, those who man the starships may be from a renascent culture on the make with fire in their guts.

My own take on Stine’s list is that the earlier items are the main drivers we can identify with today. I’ve mentioned the quest for knowledge for its own sake, a seemingly essential component of human nature. But that needs coupling with species survival. Stine doesn’t go into the matter but I’ve advocated in these pages that building our space infrastructure as a means of planetary protection will inevitably lead to deep space technologies that will boost our expansion beyond the Solar System. If so, our exoplanet discoveries — and particularly finding biomarkers in exoplanet atmospheres, which we may do within a matter of decades — would constitute a compelling reason to put a payload around another star to continue the investigation up close.

The huge costs of a star ship using known technologies make many of the historical analogies flawed. Recall that we were looking at hundreds of years of continued economic development (assuming this is possible) to afford to build a ship at the national or global level. Ideological/religious groups are not going to be able to afford one, unless development continues.

It seems more likely to me that habitats dispersed around the solar system will satisfy most of those demands. They may even be part of the economic expansion that will allow affordable starships, as trade in physical objects is viable in terms of time and energy, and information trading can be done within months, even as far out as the Oort cloud.

Which makes me wonder who, or what, will attempt star travel, and how. For example, if we posit that uploaded minds (c.f. Robert Sawyer’s SF stories)/human level AI is possible, then I would think that a good way to go is:

Send out very small probes (starwisp sized?) that can reach target destinations determined to be suitable by telescopes. Each can contain one or more seeds with the mind transference data, plus a way to construct printers to construct the [bodies of the transferees]/[robots for the AIs] at the destination.

The intelligence thus perceives the journey as instantaneous, and the artificial bodies/robots can live on any suitable world, not requiring the right biological conditions, nor contaminating any local biology if there is any.

It is a very big speculation, but it allows us colonize the galaxy without massive world ships, without 1000+ year environment recycling and stable socio-political systems, without massive energies for propulsion, without incubators for embryos or adult cryonics and revivication, etc, etc.

This allows relatively low cost colonization. If the bandwidth is sufficient, a successful probe can receive new minds and print bodies with light speed transmission.

Low cost means earlier trips, perhaps within the next century, with colonization of the nearer suitable extrasolar planets within a century after that. All this well before a human cargo or large unmanned probe as currently envisaged can even be built.

If such technologies are possible, then the various propellantless propulsion techniques , augmented with beamed energy seem like viable approaches. I would even go with bombs as propulsion if that made the outward bound acceleration and final velocity higher, with propellantless systems primarily for deceleration at the target.

Is it feasible? I would think that well within 50 years, brain simulation experiments and brain augmentation devices will indicate whether this is possible at all. I am not even sure I care whether the transferred mind is “you” or not, as long as it is recognizably human in behavior and can work in advanced synthetic bodies. Advanced AI would be fine too, although not quite as satisfactory. (I suspect that these are not mutually exclusive approach, and that synergies are very possible)

My assumption is that problems of overcrowding on Earth will demand Earth-based solutions.

Its already happened. Fertility outside of Sub-Saharan Africa is around replacement. Now we got people, mostly of a social conservative persuasion, writing books about the opposite problem. That there won’t be enough young people, or people in general, in the future.

I say we call problem solved and all go home.

Lebensraum is still necessary, not for over crowding reasons, but to build new societies free from the regulation and constraints of Earth-based governments and political ideologies.

Some of the trends toward the future envisioned in 1973, that have since

reversed somewhat.

1) The population Bomb will turn out to be bust by 2050.

2) Economics. The scarecity economies of natural resources has been

shown to be very tractable to solve in a free maket economy. Once a resource becomes scarce, technology adaps to create subsitutes (and rather fast). This is why I woould not invest in asteroid mining yet, unless you can find Ag,Au,U, in concentrated veins inside of them.

And a new trend that is not noted on Mr Stine’s list.

3) The view Humanity is nothing special, and other species needs are just

as important. That we would ruin other worlds by colonizing. I ve seen it written enough in blogs to know this is not just an inadequate 13 year olds rantings. You can occasionaly discern that some important agents capable

of moving opinions hold this view too. These are the same folk that argue

that a vast reduction in human populations is needed.

What was missed in the original list is that medical technology is pretty soon

grant lifespans of 200 HEALTHY and fertile years. I think that it might

result in a resurgence in population growth later in the 21st century. That

will reignite the Lebensraum drive.

What are the chances we can use Titan as a non-renewable energy source?

So far the energy solutions I have read about fall in two boxes: 1) Solar energy gathering. 2) Self-propulsion, using fuel produced with Earth resources (nuclear, conventional or otherwise).

But I have seen nothing published about using energy resources gathered from around our solar system.

I can picture us installing an array of beamers (for laser sails) in Titan’s orbit, with the added benefit of having a natural coolant medium on the ground.

Assuming we can deliver payloads to Titan (which we already did, with success) the main problem to solve would be transmitting/transporting the needed energy and/or fuel from Titan’s atmosphere to Titan’s orbit for the beamers array to do its job.

Have any of you guys read about similar ideas? Maybe I’m just unaware of them.

If somebody wrote about related ideas, I would like to read about it, any pointers will be appreciated.

I just found this nice article on Fox:

http://www.foxnews.com/tech/2013/05/14/warp-speed-scotty-star-trek-ftl-drive-may-actually-work/?intcmp=features

Didn’t know if anyone here had read it, but it is nice to see space articles on such a widely read site.

I’m sorry to say that the moral majority of humanity who are more concerned about the rights of alien species are never going to the stars. They will stay on Earth and go extinct like every other species before them.

As Stine noted it will more likely be outcasts like the early settlers of America who settle the stars. When we have habitats, there are going to be some groups who despise everything mainstream humanity believes in. They wont want to be part of it and wont hesitate a moment before following the generation ship approach using asteroid habitats… but bear in mind they’ll be nothing like humanity when they arrive at their destinations

Wishing Kevin F. Long would realize cheering on Space X doesn’t betray Centauri Dreams…Those destined to go into near space to work, study, and play are the ones who will travel to Earth II as only Mankind can….We should try to go to the stars while America endures…We The people won’t last forever…..Harry G. Stein’s words ‘fire in the gut’ had better be burned into all our flesh….Stein mentions a new culture vastly braver than thee may surprise billions living on all the continents by together reviving the mythic Atlantis….Not the Atlantis of the past….An Atlantis able to retrace the path that led to Altair IV…..That black swan day approaches….America’s replacement in the next century and beyond may surprise billions….The word is unprecedented…The fusion work in Europe may yet give us an engine to take us to the stars…Going to the stars may begin in Geneva….not Washington…Keep going….write more….Just do it….

Horatio Trobinson:

What energy? There is hardly any energy at Titan, compared to hereabouts. Now, Mercury, there we are talking….

Eniac says “There is hardly any energy at Titan, compared to hereabouts.”

Really how does he know? We used to think that Titan had huge deposits of ethyne. Sure, current data might suggest that some ET corporation has got there before us and mined it all, but what if it is just buried under a thin layer of sediment? In that case we could have kilograms of easily extractable stuff per square metre of surface, compared to Earth’s c300g of hard to get to stuff. Since burning oil in oxygen only gives two or three times as much energy as turning that acetylene into methane plus graphite, Titan could well stand far the better.

As for all that free sunlight on Mercury, to me the only really good place to use it would be at the poles where their if no cooling problem. I imagine that that particular real-estate would get crowded rather quickly.

Rob Flores writes “medical technology is pretty soon grant lifespans of 200 HEALTHY and fertile years” and I agree. But his conclusion about what “pretty soon“ means and how that will effect our immediate future misreads the situation badly in my opinion.

One of the leading reasons to believe that antagonistic pleiotropy sets longevity in humans is that life expectancies keep increasing linearly with time, in response to medical research’s exponential increase in knowledge. Another is that all theories that hold one factor dominating longevity in humans keep failing. The biggest clue of all is that calorific restriction seems to increase longevity right up to starvation levels, and that no singe reason for this phenomenon can be found.

To those unfamiliar with the antagonistic pleiotropy theory of aging, that last one works because starvation turns off hundreds of pathways that allow vigorous activities, so, even though starvation might only have a bad impact in itself, some of those pathways should slightly accelerate aging (though, by the precepts of the theory each impact is only allowed to be very low, or it would never have had selective advantage).

So, it is most likely that aging has so many causes, and that addressing them head-on will weaken us so much, that they can only be alleviated slowly after much research. Some won’t even be worth addressing before they have been unmasked by others.

The good news is that these are being addressed at one hell of a rate, such that, if medical research can continue its same exponential expansion of knowledge, your prediction might come true in just 600-800 years.

Oops Eniac, my ethyne reaction has five or six times less power not “two or three”, sorry.

However my conclusion still stands the same!

Rob Henry, I tend to agree that aging is not a one bullet cure.

As matter of fact I keep expressing doubts to one of my relatives about

calorie restricition’s ultimate results. What no one mentions is that calorie

restricted test animals live in a reduced state of awareness and they heal very

slowly, and (i don’t have a clinical study proving this) are more prone

to infections.

I do think that we will find multi methods of staving off aging, but it will

be in a very Frankestinan mode in this early part of this century. I expect

the 22nd century 2oo years of lifespan will be standard with little fuss.

Harry Stine was also one of the founders of the National Association of Rocketry in 1959 and it’s main driving force in it’s first few years of existence. His book, the “Handbook of Model Rocketry” is now in its 7th edition. He along with Vern Estes, Lee Piester, and Orville Carlisle started the model rocketry hobby and founded the first companies to market the hobby.

Does society want people living 200-300 years and maintaining the birth-death rate that we have now? Three humans born every second in the world, while only one dies every sixteen seconds.

And who gets to live that long? Will the treatment be for everyone or just the rich and powerful, as usual?

I remember an old quote from the Usenet about how there are people who want to live forever who don’t know what to do with themselves on a rainy Sunday afternoon.

Death may be scary, but extending lives where one still ends up in a slow misery of wasting away in their final years is worse. And if we have not solved problems like Alzheimer’s disease by then, will living longer be worth it?

@ljk

So: Even with complete and perfect immortality for everyone, our growth rate would increase only by about 2 percent (1 person saved every 16 seconds, vs 48 born in the same period). That hardly strikes me as a cause for concern. Are you sure your numbers are correct?

I am not sure what you mean by “as usual”. Most life-saving medications and treatments are very much available to everyone, within certain practical limits that many good people are working on surmounting, frantically.

Two points: 1 Why not convince MR. Bill Gates to begin serious work on nanobots? He has the money he only needs to be convinced.

2 The human race needs to know all that there is to know about the workings of the muon lepton; there is so much that we do not know about this subatomic particle and it needs to be investigated.

LJK, I must side with Eniac in thinking that the nature of your anti-longetivy anti-rich comment has the illogic typical of many tirades, however I leap to your defense in the following respect. Lifespan increases will favor the rich.

This modern mindset of encouraging equality as a goal in itself is set more by our Neolithic origins whereby we have use of a sense of envy if we are to compete with others to pass on our genes. We also need a sense of our own entitlement and revenge to help society grow through reciprocal altruism.

In that regard, mitigating differences in income Gini makes sense, and progressive rates of income tax do little harm. Trying to address wealth differences is harder, as our society is built on the capital of chronic savers, and limiting their savings would destroy the base for economic growth. The problem might be intractable, since some people will spend all their money no matter how much you give them.

Now people who are chronic savers should be able to double their real savings (by compound growth alone) every twenty odd years, so giving them 200 such years will make the wealth gap between the average saver and spender roughly a thousand times more than it is today for those on equivalent incomes (at least it should by the time they die).

That is a pure envy problem in itself, but a true problem is that some savers are far better investors than others. Those clever enough to double the average double the typical rate of return would have the problem of that gap exasperated a million fold. So, ljk how do we stop all societies wealth ending up in so few hands that it creates problems that are not just the product of primitive human psychology?!

Eniac – in this world for various political reasons , there are huge numbers of people for whom life-saving medications and treatments are very much not available to everyone. Brazil ignored US drug patents and provided AIDS drugs to its people while South Africa blocked the distribution of such life-saving drugs for years all done concurrently.

I suspect that life extending treatments will go to the rich and powerful first. Most future humans may never go into interplanetary space much less interstellar space. However, I do believe that the crews or migrants who will make the leap to the stars in what I think will be STL speed vessels (warp drives/FTLS and wormholes are not likely to happen) will be longer lived augmented humans – of a very diverse and somewhat unified humanity.

Yes, William f collins, some medical treatments do go first to the rich and powerful, for which they pay handsomely. Importantly, the effects of that on longevity is low in rich countries, such that other effects are far stronger. Things like genetic makeup or gender. I am pretty sure that you will find that, in the USA, poor female Asians have always outlived rich black men by at least a decade.

In the Star Trek universe, humans seem to have the same lifespans as they do today. I suspect that lifespan extension/human augmentations – hopefully without the accompanied dementia and other forms of impairment – are more likely to emerge in the future vice FTL/warp drive/wormholes.

The last time I checked, the rich and powerful did not give a flying fig about my viewpoints. Or the poor for that matter. So life and human society shall carry on as it usually does, stumbling forward but forward nevertheless, with lots of debris and bodies dumped off to the side of the road along the way. Either to the stars or in technological cocoons that no one wants to leave – or maybe both.

As a child of the Cold War, I am still amazed that we did not have an all-out nuclear conflict back in the day, considering how many people on both sides were just itching to push that proverbial button. Read about Curtis LeMay as just one real example of someone high up in the US military who badly wanted to take out the Soviets in a first strike. He also advocated attacking Cuba during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, which we now know would have brought devastation to much of the United States had it happened, as 44 nuclear missiles were aimed at Cuba’s neighbor to the north with orders to be launched should the island nation be invaded or otherwise attacked.

And now a quote from that great SF novel, A Canticle for Leibowitz, by Walter M. Miller:

“In conclusion,” he said, “a brief outline of what the world can expect, in my opinion, from the intellectual revolution that’s just beginning.”

Eyes burning, he looked around at them, and his voice changed from casual to fervent rhythms.

“Ignorance has been our king. Since the death of empire, he sits unchallenged onthe throne of Man. His dynasty is age-old. His right to rule is now considered legitimate. Past sages have affirmed it. They did nothing to unseat him.”

Tomorrow, a new prince shall rule. Men of understanding, men of science shall stand behind his throne, and the universe will come to know his might. His name is Truth. His empire shall encompass the Earth. And the mastery of Man over the Earth shall be renewed. A century from now, men will fly through the airin mechanical birds. Metal carriages will race along roads of man-made stone. There will be buildings of thirty stories, ships that go under the sea, machines toperform all works.

“And how will this come to pass?” He paused and lowered his voice. “In the same way all change comes to pass, I fear. And I am sorry it is so. It will come to pass by violence and upheaval, by flame and by fury, for no change comes calmly over the world.”

He glanced around, for a soft murmur arose from the community.”It will be so. We do not will it so. But why? Ignorance is king. Many would not profit by his abdication. Many enrich themselves by means of his dark monarchy. They are his Court, and in his name they defraud and govern, enrich themselves and perpetuate their power. Even literacy they fear, for the written word is another channel of communication that might cause their enemies to become united. Their weapons are keen honed, and they use them with skill. They will press the battle upon the world when their interests are threatened, and the violence which follows will last until the structure of society as it now exists is leveled to rubble, and a new society emerges. I am sorry. But that is how I see it.”

The words brought a new pall over the room. Dom Paulo’s hopes sank, forthe prophecy gave form to the scholar’s probable outlook. Thon Taddeo knew the military ambitions of his monarch. He had a choice: to approve of them, to disapprove of them, or to regard them as impersonal phenomena beyond his control like a flood, famine, or whirlwind.

Evidently, then, he accepted them as inevitable–to avoid having to make a moral judgment. Let there be blood, iron and weeping. . .How could such a man thus evade his own conscience and disavow his responsibility–and so easily! The abbot stormed to himself.

But then the words came back to him. For in those days, the Lord God had suffered the wise men to know the means by which the world itself might be destroyed. . .He also suffered them to know how it might be saved, and, as always, let them choose for themselves. And perhaps they had chosen as Thon Taddeo chooses. To wash their hands before the multitude. Look you to it. Lest they themselves be crucified.”

william f collins said on May 20, 2013 at 8:23:

“In the Star Trek universe, humans seem to have the same lifespans as they do today. I suspect that lifespan extension/human augmentations – hopefully without the accompanied dementia and other forms of impairment – are more likely to emerge in the future vice FTL/warp drive/wormholes.”

Star Trek has never been as progressive as one might think at first glance. Recall how many times Kirk talked an Artilect into self-destruction. Even Picard did not trust his own starship computers on several occasions in TNG.

Improve humanity? Heavens no, we will get Khan Noonian Singh and his eugenic superpeople! They will only use their superior smarts and physical strength to conquer the rest of us.

Most every alien intelligence is humanoid and hardly ever behaves in ways we would call truly alien. Even the nonhumanoid ones act in ways we recognize: The horta is ultimately a mom protecting her eggs. Trelane and Q act more like the petulant, selfish human-made gods of old than the supposedly far superior noncorporeal entities they are.

FYI: Even if most of the residents of the Milky Way galaxy in the Star Trek universe did come from one species long ago as depicted in the TNG episode “The Chase”, their genetics would drift after a while, especially in a few billion years, so they should all be quite diverse from the original beings. But no. Heck, in some cases, we have worlds that almost match Earth and humanity except for a few small differences!

If FTL travel was not required in the ST universe to keep things literally moving along at a fast pace, Roddenberry et al would have banned that, too. Oh wait, there was an episode of TNG where warp drive *does* negatively affect the cosmic climate and thus a Warp 5.5 speed limit was imposed. At least this misguided attempt at environmental messaging was ignored later on and has clearly been forgotten in the reimaged Star Trek films.

It’s probably not Star Trek’s fault. After all, it came from an era where incredible technological advances were expected in just the next few centuries (if not by The Year 2000 A.D.), but if you look at most of the depictions of the future from the 1950s and early 1960s (see Paleofuture), the future people look just about the same and gender roles are still of the man works and explores, woman stays home to cook, clean, and raise children status quo.

The original Star Trek series was guilty of that last trope numerous times, including the very last episode aired in 1969 where it was stated more than once that women were not allowed to command Starfleet starships. It only took until 2004 and well into the 24th Century for that to change in the Federation, at least on a regular TV series basis.