The recent news about an ocean on Enceladus had me thinking over the weekend about a trip my wife and I took years ago to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. There we had rented a cabin for the week on the shores of Lake Superior, twenty miles from the nearest town, unless you counted the small grocery store, art gallery and scattered houses up the highway as a town — if so, it was a tiny one. Looking out across the silver and gunmetal gray waves of Superior, you could imagine it an ocean, a cold, frothing place of treacherous currents and, that October, raw winds.

Lake Superior appears as the comparison in many of the reports on the Enceladus findings as they sketch out what appears to be a sea just as large, perhaps ten kilometers deep covered by an ice shell four times as thick. Given that the well known plumes of Enceladus are already known to contain organic molecules in addition to salty water, the inevitable question arises: Could some form of life exist beneath this frozen surface? There’s no way to tell as yet, but the imperative to probe still further into the tiny world (504 kilometers in diameter) continues to grow.

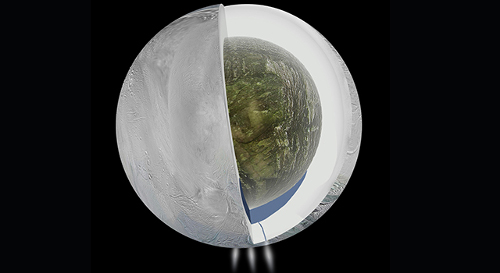

Image: This diagram illustrates the possible interior of Saturn’s moon Enceladus based on a gravity investigation by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft and NASA’s Deep Space Network, reported in April 2014. The gravity measurements suggest an ice outer shell and a low density, rocky core with a regional water ocean sandwiched in between at high southern latitudes. Views from Cassini’s imaging science subsystem were used to depict the surface geology of Enceladus and the plume of water jets gushing from fractures near the moon’s south pole. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

What we have in the latest work is the result of three Cassini flybys, two of them over the southern hemisphere, one over the north. The tiny deviation of the spacecraft from its trajectory — the velocity change was 0.2-0.3 millimetres per second — could be detected in Cassini’s radio signals, helping us measure variations in the gravity of the tiny world. The payoff is explained by Luciano Iess (Università La Sapienza, Rome), lead author of the paper in Science:

“By analysing the spacecraft’s motion in this way, and taking into account the topography of the moon we see with Cassini’s cameras, we are given a window into the internal structure of Enceladus. The perturbations in the spacecraft’s motion can be most simply explained by the moon having an asymmetric internal structure, such that an ice shell overlies liquid water at a depth of around 30-40 km in the southern hemisphere.”

These measurements are extraordinarily fine, but analysis of the Cassini signal can detect changes in velocity as small as 90 microns per second, according to this JPL news release. Although the southern polar region has a surface depression that affects the local pull of gravity, the magnitude of the gravitational dip is less than it ought to be given the size of the depression, which leads to the finding that a high density feature beneath the surface is the cause. Denser material, probably liquid water, compensates for the missing mass. This water may or may not be the source of the south pole plumes Cassini has observed in the past, but that possibility certainly exists.

Meanwhile, I’m recalling an earlier encounter with Enceladus. Freeman Dyson was talking about the moon as a target for the Orion spaceship in the late 1950s, and in a twelve-page report in 1958 called “Trips to Satellites of the Outer Planets,” he made the case for visiting the gas giant moons. Decades later, he would explain his thinking to his son George, as recounted in the latter’s Project Orion: The True Story of the Atomic Spaceship (Henry Holt, 2002):

“We knew very little about the satellites in those days. Enceladus looked particularly good. it was known to have a density of .618, so it clearly had to be made of ice plus hydrocarbons, really light things, which were what you need both for biology and for propellant, so you could imagine growing your vegetables there. Five-one-thousandths g on Enceladus is a very gentle gravity — just enough so that you won’t fall off.”

Amazing to recall that, at least for a time, the motto of Project Orion was “Saturn by 1970.” But it’s clear from everything we’ve learned about this moon since that Enceladus remains a primary object for study, even if we’ve now moved into the realm of astrobiology. What a surprise that would have been to the Orion team back in the 1950s!

The paper is Iess et al., “The gravity field and interior structure of Enceladus,” Science Vol. 344, No. 6179 (4 April 2014), pp. 78-80 (abstract).

A surface grazing probe equipped with a gas/liquid chromatograph and a mass spectrometer to sample the plumes seems like an obvious way to go to determine if there is any possibility of life beneath the surface by analyzing the organics. If the plumes have been active for a long time, we might also expect material to have accumulated on the surface, despite the weak gravity. Instruments to analyze that material, either from the grazing orbit, or on the surface would also be worthwhile.

I am skeptical that such an energy poor environment will support life, but I would welcome a surprise. Perhaps a relatively inexpensive probe might contribute to answering that question.

In the final quote Freeman Dyson presumably means the density of Enceladus is 1.618g/cm^3 (the correct figure), someone who just reads the quote probably would think it means 0.618 g/cm^3

Seems that our solar system’s habitable zone may extend to Saturn now :)

If someone ever writes a book titled ‘Amazing things that never happened’, one of the first chapters should be about the Orion nuclear-pulse spacecraft

The stuff dreams are made of, Paul… Thanks for the inspiration! Nice save from the precipice of overwhelming sadness felt in reading the findings of the climate change report. Been out of the loop for a while/finally have internet again after 17 months. It’s snowing in Fairbanks, Alaska this morning with temps near freezing after a week or so of intense sunshine and rapid snow melt. We’re back to long days after too many months in the dark. Eyes are still adjusting. I’m enjoying a stiff cup o’ joe & celebrating my return to the internet at Centauri Dreams~*

(I have a lot of reading to catch up on)

Kari, what a surprise! A pleasure to have you back.

I have always thought the moon had a dense core and due to inertia differences grinds against the outer more mobile ice sheath which generates heat. The interesting thing here is not only heat and liquid water but also nutrient rich material most likely mixed with organics. Quite a nice place for a microbe don’t you think. Landers please!

Depressing. Unless there’re some major breakthroughs most of us will probably die of old age before we learn much about either Europa or Enceladus. If only Orion hadn’t been shelved.

david lewis: if only. George Dyson has 300 cassette tapes of Orion interviews of people now gone. I asked him for a chance to transcribe them, but he passed on that. Had the political climate been different and an exception made for “peaceful” use of space in the atmospheric nuclear test ban treaty, we might have had crews to Saturn and back on 2nd or 3rd generations of the design by now. We might have a deep space communications network and propellant depots. Sure, we would have had radioactivity in the atmosphere, but Fukushima, Chernobyl, and Three Mile Island make it clear that we get that benefit over time anyway as reactor accidents occur.

Given that Enceladus is in a much more benign radiation environment, and its plumes seem to be more active than Europa’s, I would think it would be the top spot for exploration.

David Lewis Time we began to think seriously about living longer then!

And another thing, E/m communication latency over long distances is already an inconvenience.It will be a considerable handicap to communications over even greater distances unless we can overcome the light speed limit . there has to be another way!

@Czuba

Sir – I’d suggest that you go ahead and try again with Mr. Dyson. I imagine that those 300 tape recordings are quite valuable and would do a lot for history of science if they were transcribed. If I was you I would approach him again, and if need be again and again stressing the importance of what he has. Are at least try before he has a chance to erase them.

More on a possible sample return mission to Enceladus:

http://online.liebertpub.com/doi/full/10.1089/ast.2014.1158

I’ve been mocked for asking this on the BAUT forum but no one actually responded to the question so I’ll try here: Should we petition Caroline Porco or someone with the clout to redirect Cassini, at the end of its mission of course, to fly through the Encedalian(sic?) plumes in an effort to adsorb some brine? If enough fuel could be saved to then point the probe back towards Earth…they seem so good at slingshot mechanics. Wouldn’t it be worth trying to get a crude sample back to near-Earth space? We could worry about a mission to scrape and collect later. How completely insane would that be?

Alex Tolley says “I am skeptical that such an energy poor environment will support life ”, and I must disagree.

In this system much material is cycled through the E-ring, and returned to the moon as high energy compounds. Currently, life has much more potential than Europa, the true problem being how long these energy intensive geysers could keep up their current levels of activity. Currently, the smart money would be on ‘not nearly long enough’

“Seems that our solar system’s habitable zone may extend to Saturn now :)”

Well, that is because, quite frankly, there is no single zone. Environmental conditions create habitable zones in multiple instances, it is not just about the right distance from a star. Every sizable body creates a respective niche. A galaxy core does (by creating conditions for stars with planets where life may be possible), stars do (due their Goldilocks zone) and also planets do (due to gravitational influence on their lunar system). Comets may also be viable candidates respectively when considering microbial life. Maybe it is time to come up with some calculations constraining the limits for these niches.

There are two known niches in the known solar system around the outer planets (Saturn and Jupiter respectively). However, even that may just be the tip of the iceberg. There has been considerable debate about larger bodies in the Oort cloud (Nemesis, Tyche, etc) because all observations seem to indicate a certain necessity for “disturbator” in the Oort cloud with respect to comet frequency, geological record and quite frankly mass extinctions. Usually the idea is quickly waved away, but with the discovery of Sedna and quite recently the dwarf planet Biden and their quite unexpected orbits there is already talk about an object of about 10 Earth masses out there. If it exists, it is likely to harbor its own lunar system and with it also the possibility for another niche ~1-1.5 light years from the sun.

One can imagine photos of ET fish or other animals gracing the front cover of National Geographic magazine. What a valuable sensation that would be! We should definitely send an ice melter to have a peak into the ocean. At 0.005 G, the pressure will not be too great at depth.

I’ve always been fascinated by the notion of plant like animals or blends of plants and animals. It is indeed interesting to speculate on the current ongoing phase change of our universe, the emergence of life. We know for sure that it has happened at least on one planet which is our present home planet, Earth .

@Tulse

Regarding radiation’s effects on Europa, this article is well worth reading if you haven’t seen it already: http://www.astrobio.net/exclusive/3010/hiding-from-jupiters-radiation

In summary although the huge radiation from Jupiter is very problematic, it may actually provide a vital energy source for an oxygen-depleted ocean, also, the leading hemisphere, which is less radiated, also has a coating of up to 3m of regolith due to micrometeorite bombardment – so it’s thought there may be some sweet spots

A few years back, radio astronomer and 3D artist Rhys Taylor was so fascinated by the Dyson interest in an Orion drive mission to Enceladus that Mr. Taylor made an illustration of it

http://www.rhysy.net/OrionGallery2/index.php?gallery=.&image=Enceladus%201970%202.jpg

@coacervate April 7, 2014 at 19:48

‘Should we petition Caroline Porco or someone with the clout to redirect Cassini, at the end of its mission of course, to fly through the Encedalian(sic?) plumes in an effort to adsorb some brine? If enough fuel could be saved to then point the probe back towards Earth…they seem so good at slingshot mechanics.’

There is not enough fuel even with slingshot maneuverers to get out of Saturn gravitational field.

@Lionel April 8, 2014 at 9:25

‘Regarding radiation’s effects on Europa, this article is well worth reading if you haven’t seen it already: http://www.astrobio.net/exclusive/3010/hiding-from-jupiters-radiation‘

There is an error in the article, the magnetic field is 10 000 times stronger than the Earths, not 10.

@swage

Nice reply

The reasoning about niches within the lunar systems for an Oort cloud gas giant easily is extended to rogue planets too. I’ve noticed rogue planets are almost always described as having been ejected during early stages of star formation, but there is another stage of ejections during the later stages of stars lives / deaths. At whatever stage it happens, some proportion of ejected planets would retain their moons

I see that the first candidate exomoon for a rogue planet was announced in Dec 2013 … http://arxiv.org/abs/1312.3951

“There is not enough fuel even with slingshot maneuverers to get out of Saturn gravitational field.”

Can we fire a beam at it to accelerate it into a slingshot maneuver that does?

Regarding what is done with Cassini, I have been wondering whether using Titan’s atmosphere to aerobrake and enter into a stable orbit around Titan might be better than crashing the probe into Saturn. Wikipedia’s Cassini-Huygens Retirement page shows that during a 2008 review, Cassini aerobraking into orbit around Titan was considered possible, whether it remains possible with diminished fuel I don’t know. Titan is such a dynamic place that I think an orbiting probe would yield so much science… and it’s going to be a very long time before we have another chance at a Titan orbiter

(Also regarding comments about, the same Wikipedia page shows that back in 2008 there was still enough fuel to leave the Saturnian system and move over to Jupiter. If this was the case then probably it was even possible to eventually get an Enceladus brine sample back to Earth by following the Interplanetary Transit Network ‘tunnels’ between Lagrange points. How long this would take I don’t know… and the organics in the sample probably would be long long gone due to radiation

I have been trying to find a list of journey times via the Interplanetary Transit Network but haven’t tracked one down, has anyone seen one? I just remember between Earth and Mars takes about 10,000 years but some other destinations are perhaps ten or less.)

@swage April 9, 2014 at 5:50

‘Can we fire a beam at it to accelerate it into a slingshot maneuver that does?’

If only, firstly it is too small a target, secondly it has little protection against a fast particle beam and thirdly Saturn’s magnetic field would make targeting difficult even if the beam was neutral.

So clearly the rule for habitability should not be “follow the water” but “follow the letter E”. Earth, Europa, Enceladus…

;-P

I’d like to see the solar system criss-crossed with a mesh of petawatt beams for propulsion and power, courtesy of old sol. Last I checked we could build mirrors.

Andrew Palfreyman:

When have you last seen a petawatt beam made with mirrors? Turns out this is not possible.

@Andrew Palfreyman:

‘Last I checked we could build mirrors.’

We will be riding on particle beams to the stars.

I’m more optimistic that we could send a sample return mission to Enceladus in the near term. First of all to get to the subice ocean we could travel through the vents:

A look at Enceladus’ plume.

http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/cassini/multimedia/cassini20080207.html

Secondly, NASA is considering the possibility of using the SLS for a sample return mission from the outer planets’ moons:

SLS capability touted for Europa Lander capability, Enceladus sample return

January 6, 2012 by Chris Bergin.

http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2012/01/sls-capability-europa-lander-capability-enceladus-sample-return/

Bob Clark