J. G. Ballard (1930-2009) emerged as one of the leading figures in 20th Century science fiction. His fascination with inner as opposed to ‘outer’ space infused his characters and landscapes with a touch of the surreal, taking the fiction of the space age into deeply psychological realms. Christopher Phoenix here looks at the question of centuries-long journeys to the stars, with reference to a Ballard story in which a crew copes with isolation on what appears to be an interstellar mission. What we learn about ship and crew informs the broader discussion: If it takes more than a single generation to make an interstellar crossing, what can we do to keep our crew functional? And is there such a thing as happiness under these constraints?

By Christopher Phoenix

A few months back, Centauri Dreams ran Gregory Benford’s review of Kim Stanley Robinson’s novel Aurora. After reading that review and the discussion that followed, I began thinking about fiction that explores how starflight might fail. I hope that we will reach the stars someday, but it is always interesting to step back and explore the reasons why interstellar flight might not be an inevitable part of our future.

Perhaps due to science fiction’s roots in the pulp magazines of the 20s and 30s, many SF stories show an unwavering faith in humanity’s ability to overcome any obstacle. In most science fiction, it is a foregone conclusion that humanity will reach the stars. Space opera stories expect that the reader will accept the existence of a human interstellar civilization from the very first pages. Stories that dispute this assumption are much rarer.

One such story is James G. Ballard’s “Thirteen to Centaurus”. This short story takes place within a mysterious habitat known only as “The Station” by its thirteen-person crew. For generations, they have lived within the confines of the Station’s three decks. At the beginning of the story, one of the teenage members of the crew, a boy named Abel, suffers recurring nightmares of a burning disk. The only person who can tell him the meaning of these visions is Dr. Francis, the Station’s doctor, who lives alone on another deck.

Dr. Francis tells Abel that the Station is actually a starship traveling to Alpha Centauri and explains that the burning disk is a repressed genetic memory of the Sun he has never seen. When Abel asks Dr. Francis when they will arrive, he explains that the Station is a multi-generational spaceship. None of the current generation will live to see planetfall. Dr. Francis tells Abel that the rest of the crew cannot know this truth, as otherwise they will never be happy in their confined artificial world.

Soon, however, the story takes another twist. It turns out that Dr. Francis is lying, and the Station is in fact an Earth-bound experiment designed to test whether humans can survive a century-long flight to Alpha Centauri. In truth, Dr. Francis is one of the researchers posing as a member of the crew, sent to secretly observe them from among their midst. The Station’s planners believed that humans could not survive such a trip knowing that they are condemned to live their whole lives in a confined spacecraft. Generations of crew will never see the Earth where they came from or live long enough to reach their destination. To solve this problem, the researchers use hypnotic suggestion to eradicate memories of Earth and make the crew accept the Station as the only world that exists.

Image: Science fiction writer J. G. Ballard.

As the story continues, we see Dr. Francis leave the habitat to meet with his colleagues. To his horror, his superiors tell him that the project must be shut down due to lack of public support. They ask Dr. Francis how to transition the crew from their isolated life in the station to the outside world. Hoping to convince them to continue the simulation, Dr. Francis insists that the crew cannot survive having their worldview shattered in this way. The only way to humanely end the project is to stop the crew from having children and wait for the current generation to die out. His superiors are so desperate to end the project that they agree to take this extreme course of action.

As the experiment is gradually shut down, Abel begins to ask Dr. Francis awkward questions about the Station. Dr. Francis’s clumsy attempts to hide the true nature of the Station only seed Abel’s mind with further doubts. In a more disturbing turn, Abel begins showing an unhealthy interest in performing psychological experiments of his own devising on the other members of the crew and even Dr. Francis himself.

Unwilling to accept the termination of the project, Dr. Francis finally decides to seal himself inside the dome to complete the imaginary trip to Centaurus with the crew, knowing that no one will dare enter the habitat to remove him. Once within the habitat, however, he realizes just how monotonous the crew’s life really is. Unfortunately, he dares not leave, since entering the habitat without permission carries a mandatory 20 year prison sentence. At this point, Abel takes the opportunity to turn the tables on Dr. Francis, forcing him to participate in his psychological experiments as a subject. Abel has begun to run the Station like a minor tyrant.

In the end, Dr. Francis finds a hole in the outer dome through which the previous captain and Abel have observed supplies being brought into the habitat. He realizes that the captain knew the truth and choose to stay in the dome. Before he died, he told Abel, and Abel has chosen to feign ignorance and stay within the station so that he can be the de facto ruler of this tiny world.

Trapped in a Tin Can

Ballard questions whether humans can adapt to life in a multi-generational starship. In his story, the designers of the Station believe that people would find their life in such a ship so limited compared to life on a planet that they could never be happy. Their solution is to eradicate the crew’s awareness of any other possible existence. This one idea drives much of the design of the Station.

The Station’s planners attempt to achieve this goal by using hypnosis and subliminal suggestion. The crew only believe themselves to be happy because they are conditioned to do so. Subliminal messages have been embedded in educational tapes that the crew are required to listen to at regular intervals. The message that there is no life beyond the Station is constantly reinforced by these tapes. In addition to this regular conditioning, every aspect of the crew’s’ life is scheduled and controlled. They have no freedom of thought or action. Since they are supposed to believe that there is no life beyond the Station, the crew has no access to the books, art, and culture of Earth. Even though this sort of highly effective “mind control” doesn’t really exist outside of science fiction, Ballard presents a stark view of what life could be like in a multi-generational starship. Even if this scheme could work, it would only be at great psychological cost to generations of crew.

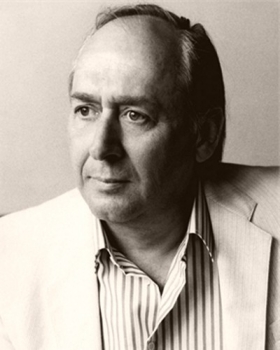

Image: “Thirteen to Centaurus” can be found in, among other places, The Complete Stories of J. G. Ballard (Norton, 2010).

Ballard is not alone in his opinion. If you mention multigenerational spaceflight, many people will tell you that it is incredibly unfair to condemn generations of people to life aboard a ship in interstellar space. The idea that it will be impossible to be truly happy in an artificial world that you cannot escape drives much of the criticism of multi-generational spaceflight. Ballard has clearly touched on a tender nerve.

In the story, however, Dr. Francis finds that not all is as it seems. After sealing himself in the simulator, he discovers that the late captain and the teenage Abel both knew that they were in a habitat on Earth, and yet they chose to remain. For Abel, staying in the habitat gives him the opportunity to dominate the other members of the crew and force them to participate in his psychological experiments.

Here, Ballard raises another disturbing question. In an enclosed habitat, might one ambitious individual or small elite group seek to control the rest of the crew? Aboard a starship in interstellar space, there would be no external checks on oppressive leadership, or any way to escape it. Because of this, choosing the right form of governance would be vital for a generation ship. Unfortunately for the inhabitants of the Station, the researchers put all their trust in their mind-control methods. They did not have any means to check someone, like Abel, who broke beyond their mental blocks.

This story reminds us that we must plan for the social and psychological factors of multi-generational trips as carefully as we do for the purely mechanical ones such as life support, radiation shielding, and propulsion systems.

Losing Enthusiasm

In Ballard’s story, the people running the century-long simulation decide to shut the project down midway. When the project was started, humanity was attempting to colonize the Moon and Mars. The public was enthusiastic about space travel, and many people believed that they would eventually build interstellar ships. So, it was decided to test social conditions on such a trip even before the technology to build a starship or a self-sustaining habitat was available.

When the story takes place, the Lunar and Martian colonies have failed. The public is no longer interested in space travel. Furthermore, they have begun to question the ethics of sealing generations of people in the simulator and observing their every move. Almost everyone wants to end the project.

Ballard suggests that humans will have difficulty maintaining focus and enthusiasm long enough to complete a prolonged effort like developing interstellar travel, which could take centuries. A case can be made for this argument by just looking at our history. Even though we reached the Moon, politicians chose to cancel the Apollo program. In the years that have followed, the numerous plans to return to the Moon and/or go to Mars have been not been carried out. Astronauts have not even ventured beyond low-Earth orbit since the Apollo missions.

Currently we don’t have a replacement for the space shuttle, or a coherent plan of what to do to follow up on our current space probe missions and the ISS. It often seems that ambitious plans to explore space are more likely to fail because of lack of political support than technological obstacles. Human civilization will need to develop a much longer planning horizon than we currently have to maintain the political will needed to develop interstellar travel.

Our lessons come from the journey, not the destination…

Ballard raises many interesting issues in this story. However, despite the melancholy ending of “Thirteen to Centaurus”, I’m still quite optimistic about the future of multigenerational space travel. Personally, I believe that it’s possible for humans to be happy aboard a generation ship in deep space, even knowing that they will not live to see their destination.

When a group of people set out on an interstellar journey that only their descendants will complete, the ship will become their home as well as the home of the generations between launch and planetfall. Therefore, I propose it is more important to plan for the interstellar journey than to fixate on the destination. We must plan the voyage so that the people who are born, live, and die on the spaceship have the opportunity to live full lives.

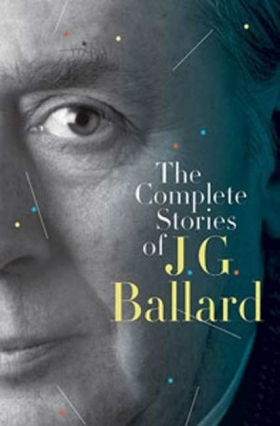

Image: Ballard’s work occasionally made it to other media, most notably in the 1987 Spielberg film Empire of the Sun. This is a shot from a TV adaptation of “Thirteen to Centaurus,” as presented on Out of the Unknown, a BBC science fiction anthology series broadcast between 1966 and 1971. Starring were Donald Houston, John Abineri, Robert James and Noel Johnston.

The common objection to multi-generational spaceflight is that the crew will not be happy with their lives aboard the ship, or that they will even “go mad” from the psychological strain. Why should the crew go mad on a generation ship? Ballard’s story suggests two main reasons. One is lack of space and forced lifelong contact with only a few people, and no way to escape someone you do not wish to know. The other is a feeling of deprivation from being born on a starship, not on a planet of your own.

The first problem can be solved by simply sending a more reasonably sized crew. In Ballard’s story, the Station’s population is a scant thirteen, not nearly enough! So far, most population size studies for starships have focused on genetic factors or maintaining specialized skill sets, not on social or psychological needs. I’ll make a stab and say that a crew size of at least a few hundred people, similar to a typical Medieval village, will provide ample choice in human contacts.

Earlier, I touched upon the issue of leadership. Since there will be no possible external checks on dictatorial behavior within an isolated starship, we must choose the right form of governance at the beginning of the trip and place what safeguards we can to avoid abuses of power. While a certain amount of centralized authority will be necessary to respond to emergencies, the people responsible for the day-to-day life of the crew should not be autocratic or oppressive. The leadership must be flexible enough to accept any changes that will become necessary during the course of the trip. This suggests the traditional military-style command structure used on all crewed spaceflights since the Cold War will not work for multigenerational spaceflight.

But what about lack of space? In “Thirteen to Centaurus”, the crew was confined to only three decks. I don’t think any crew could thrive, or even survive, in such cramped conditions. We must provide the crew with sufficient space. I am of the opinion that a sufficiently spacious ship-style interior could work for people who have adapted to life in space habitats. Garden spaces can be incorporated into the interior design, creating a more naturalistic environment, unlike the harsh mechanized interiors described in many science fiction stories. But it is also possible to create a starship large enough to contain an open Earth-like landscape.

The largest generation ship concepts are designed like traveling O’Niell colonies. Such “world-ships” can contain an Earth-like landscape on their interior, including an artificial sun, creating an environment almost like an inside-out planet in miniature. The main problem with such a scheme is constructing and launching such a gigantic structure, but such a craft can offer an Earth-like existence during a long flight.

But will the crew feel deprived living their entire lives away from any planet, as the researchers in Ballard’s story believe? I think Ballard misses the mark here. We neither choose nor tend to question the environment we are born into. The crew of an interstellar ship would accept their environment as normal, just as countless people throughout history have accepted their unique environment on Earth as “normal”.

To modern first-world people, the idea of living and dying within a relatively small area like a generation ship seems impossible, but the amount of mobility available to us is unusual compared to the lifestyles of earlier people. It is even possible that people who have lived their entire lives in space will think of living on a planet as something strange or even unpleasant. They may wonder how we put up with weather we don’t control, or a constant gravitational acceleration we can’t modify to our preference just by going to another deck. On the other hand, things we see as strange and maybe even frightening, like relying for our very survival on ship systems continuing to function, will be accepted as normal by them.

Only time will tell if human civilization can muster the energy and will to send starships to the potentially habitable exoplanets we discover around nearby stars. But if we do, I firmly believe that people will be able to live happily aboard those ships. Even though these voyages will realistically take centuries to complete, humans possess the flexibility and resilience to adapt to life in almost any environment. Certainly, the culture aboard such a ship would not be anything like modern life on Earth, but that does not mean that such a culture could not be as complex and fulfilling as any throughout human history.

Why should the crew be happy? What matters is that they should do their jobs and help get the generation ship to its destination. That is the goal to which everything else must be utterly subordinate. The culture on the ship does not need to be “complex and fulfilling”; what will only matter is that it works, and works reliably. In other words, it must be the opposite of “dysfunctional” – it must be functional.

There are two reasons why the crew’s happiness is important. One is ethical. Many people will not support interstellar flight if our plans include sealing generations of people in starships with the expectation that they won’t be happy. People no longer support systems and societies that strip individuals of what we regard as basic rights, and that will include a hypothetical starship in which the inhabitants are expected to do nothing more but breed in captivity and repair ship systems for generations.

More importantly, your plan won’t work. A society in which every generation is expected to sacrifice their personal happiness for “the good of the mission”, without even a by-your-leave, is exactly the sort of culture that will turn dysfunctional. For the first generation it might work. They will have chosen to sign up for a star mission, and they may regard it as important enough to soldier on even though they know they will die on the ship. This is more extreme than current space missions, but it still falls within the model of carefully picked astronauts doing a job they choose to do. It still might not work. Even professional astronauts can become fed up with the mission, as the tensions between the crew of Skylab 4 and Mission Control demonstrated.

But what about the later generations? They will not have chosen to be on the ship. Neither will they have been carefully picked to be psychologically compatible with each other and dedicated to the mission. Children rarely identify entirely with their parents, particularly when they are being told that their happiness doesn’t matter. The second generation will probably not want to comply with their parent’s vision, especially since no one ever asked them if they wanted to go. The second generation may entirely turn against the mission and blame their parents for having trapped them on this ship.

How will your culture deal with disobedience? I’m guessing that they will turn to coercion and punishment. A cursory look at our own history shows that governments that try to force people to comply with systems that they do not believe in rarely succeed. In a starship, there will be nowhere to escape from these tensions.

However, it will be easy for disaffected inhabitants to strike back at the ruling faction on a starship. Their environment is so fragile that all they need do is take over an environmental control section or other vital system and threaten to destroy it if their demands aren’t met. Such terrorist action could be deadly to all involved, but that will not stop desperate people. Sufficiently angry individuals may even choose this course of action as revenge against the people who confined them in a ship in interstellar space.

In a single generation, the rigid shipboard structure you describe will have become entirely dysfunctional. I believe that the only way to design a functional generation ship is to make sure that the inhabitants can live fulfilled lives aboard the ship. Most people will care more about their day-to-day life than about grandiose pronouncements about “the mission”. If they are expected to sacrifice personal happiness, personal relationships, and every last modicum of self-determination in the name of “the mission”, they will probably come to hate that mission.

So, by your own design criteria, I think that the starship must be designed to ensure the happiness of every generation from launch to planetfall. It must be a self-contained world in its own right, with its own language, cuisine, forms of entertainment, and all manner of activities that are not in any way related to “the mission”. This is the only way to ensure that each generation will take up their parent’s role and help the starship to its eventual goal. In a properly designed starship, there will be no conflict between helping complete the mission and and living a happy life.

You are extrapolating from the behavior of trained astronauts and explorers. The people who are loaded onto a generation ship to constitute the first generation will be of a completely different sort. Probably they will have been bred and modified specifically for the task. They certainly won’t have been taken from the general population. That simply wouldn’t work over the long term – and this is a very long-term project. And no, it won’t be ethical by your standards, in any shape or form. It is a human engineering project in the toughest sense.

The sort of modification you are describing isn’t even possible. You cannot use genetic engineering to modify higher order traits. Such things as personality emerge from innumerable factors and cannot be controlled by changing single genes. A mission based on your ideas has as much hope for success as a flight to Mars based on the Ptolemaic model of the solar system.

And even if you could “modify people for obedience” or something like that, such mindless drones would be entirely unsuitable for star travel. We must be as adaptable as possible to survive an interstellar journey, both intellectually and genetically. A rigid monoculture like you are describing would fail over any truly long-term timeframe. If the crew cannot think for themselves outside of a rigid set of rules set up by the creators of the ship, they will not be able to solve the problems they will encounter. If they are all of a single genetic type “modified for obedience”, a single disease could wipe them all out really quickly.

So, no, starflight cannot be a “human engineering project” in the sense you are describing. Such a plan could never work. Now, what I have said above only applies to the idea of controlling behavior by manipulation of such mythical entities as “sanitary engineer genes”. Genetic modification may play a vital role for adapting humans to life an extrasolar planets. But such changes will apply to our biological bodies, not give researchers the ability to make us good at basketball or music. Do you think that if we cloned Micheal Jordan, the clone would inevitably become an NBA star? It’s not just genes that make us what we are, but our upbringing, our unique experiences, and our choices (like pursuing sports). The clone might be terrible at basketball, or never even touch a ball. The world isn’t as simple as you think.

How do you know that in the future it won’t be possible to use genetic engineering to modify higher order traits? Obviously human-modification technology will evolve greatly over the coming decades and centuries.

You say “such things as personality emerge from innumerable factors and cannot be controlled by changing single genes.” Not single genes, no. But not innumerable, either. Just multiple. Nobody said that it would be easy! It’s not easy to build the ship either.

I disagree absolutely with the idea that “if the crew cannot think for themselves outside of a rigid set of rules set up by the creators of the ship, they will not be able to solve the problems they will encounter.” Thinking for themselves during the trip will be a recipe for disaster, because the ship will be a delicate and unchanging environment – or rather, any change will be for the worse, and probably disastrous.

Of course the psychological attitude required for colonizing the destination planet will be a completely different one. There, an intelligent, flexible, aggressive, combative, competent, and adaptable approach will be absolutely essential. Yes, the problem of the attitudinal switch when the last generation is to be produced is a very interesting one.

Because higher order traits do not emerge from genetics alone, but from innumerable other factors such as upbringing, personal experience, and the quirks of how our bodies develop. No amount of genetic tweaking can ensure that all individuals will turn out the same. It’s the same as with the clone of Michael Jordan. There is no guarantee that he will be an NBA star, just because he shares the same genetics.

There simply isn’t any simple relationship between single or even multiple genes and such things as obedience, musical ability, and so forth. You can’t do what you describe simply because the human body does not work that way. You might as well argue that we could ensure the crew behaved themselves by draining off some of the vicious humors with Medieval-style bleeding. The body simply doesn’t work in the simplistic way you describe. You can’t design a genetic technology off your flawed analysis any more than you could plan the starship’s trajectory using the Aristotelian laws of motion.

Here we have a strong difference in opinion. I think that trying to keep the society aboard the starship from ever changing will doom the mission to disaster. Look at societies on the Earth today. Human society is always changing, and it never goes well for people who would like to stand in the way of that. And it simply isn’t necessary – or even desirable – to prevent the shipboard society from ever changing.

And how can you be so sure that any change from what you envision will be for the worse? Can you foresee everything that will happen on the journey? And how can every conceivable change be for the worst? Maybe, a century into the mission, the crew decides to change how families are organized so more than two adults are involved in raising children. How will that doom the mission? Maybe the crew decides they want to change the interior decor. Will the starship instantly explode because of this? Maybe, because of new requirements, the crew wishes to shuffle around some of the partitions and divide interior space differently. How will this be a “change for the worst”? Perhaps the system of government set up at launch is no longer adequate to deal with some of the administrative problems. Therefore the inhabitants change some aspects of the constitution. Does this mean everyone will go and start smashing ship equipment, or that the starship will instantly plunge into the nearest black hole? Inevitably, the crew will begin using different words for new things and experiences and dropping old words that have little meaning to them. Will it harm the starship if the worlds “ski”, “snowball”, and “horizon” fall out of use among the starship’s youth?

I propose we do the opposite of what you describe. We can be sure that the society that is aboard the ship will change. Any effort to stop it from changing is doomed to fail, and will probably result in the failure of the mission itself. So we must ensure that the culture aboard the starship is free to change and develop new ways of thinking and doing things on their century-long voyage. Change doesn’t mean change for the worst.

Also, absolute governmental authority isn’t a good thing. It isn’t hard to imagine an Abel-like figure taking advantage of an authoritarian power structure aboard the ship to fulfill his own desires, which may not be good for the mission at all. The phrase “absolute power corrupts absolutely” comes to mind here. How are you going to ensure that the shipboard government continues to cooperate with your vision? My starship would have a system of checks and balances established to prevent misuse of authority, but yours could have none.

While switching from ship-board to planet-based life will be big change for those who decide to land on a planet, I do not believe it will require any big attitude shift like your describe. If they are as intellectually disabled as you insist they must be, they will not have survived the voyage.

Thomas Goodey, I’m not sure that there is such a dichotomy between a happy crew with a “complex and fulfilling” environment and a functional ship-culture that furthers the mission. Both components are necessary for success, one should think. After all, we aren’t talking about a submarine crew on a short-term deployment, here, but an entire micro-civilization that has to endure and develop over a period of centuries.

I disagree. If the crew is not happy; if all that matters is “doing their job” eventually they will mutiny.

Depends how it is set up. What’s certain is that a mutiny wouldn’t do them any good.

That may be but the pleasure of firing a tyrannical captain through an airlock into deep space maybe greater than the punishment…

It’s hard to see exactly what punishment would be possible with Earth two light years away.

What’s Earth got to do with it? A perceived-criminal could be executed, or imprisoned, or starved, or tortured, or just held up to public opprobrium (stocks, pillory, or the like).

Your vision of life aboard a starship is worse than Ballard’s! Violence and cruelty breeds anger, hatred, and more violence, so I hope we will have outgrown that before we try living in a fragile starship. We will have to be far nicer to each other on a arkship than we have been to each other on Earth. An arkship is far to fragile to survive a violent conflict.

But going on these lines, once the reigning authorities on the ship have all been herded into the airlock and ejected, no one will remain to punish the rebels. Or, rather, they will probably just shoot or stab their former leaders and recycle their bodies so as to not to waste their constituent elements. The rebels don’t have to worry about punishment after that.

I will point out here that it will not be possible to execute or starve everyone. If enough of the population is killed off, either by draconian punishments or in a ship-wide battle, the starship will be in real trouble.

I propose that we need a new social contract aboard a starship. Not one based on threats of violence and coercion, but on mutual cooperation and interdependence. Violence breeds violence, and we cannot afford to shoot holes in the hull of the starship. Can you name me any instance in history when the threat of violence or even death prevented insurgencies and terrorism? Nor do we need the threat of violence to ensure everyone wants to take care of their starship home. It is the source of all life for the crew. Taking good care of it goes hand in hand with the goal of living a happy life. It’s the same on Earth, we just haven’t quite accepted that our planet home can’t absorb any amount of damage yet.

Punishment, perhaps no more data transmission until the individuals are dealt with.

I agree with Christopher. People who lament about conditions within an ark fail to realize that in most ways the life will be far superior to most lives on Earth today. Even less realized is that for most Human Beings that have ever lived, the social constraints were no less than those on a starship. Most of these could no more have escaped their social straitjackets then you could step out of an airlock.

I do believe that we must design an ark to give those aboard it a chance to live a fulfilled life, and so avoid the situation described by Ballard, but you are quite right that life aboard an ark could be better than many people’s living conditions on Earth. Social constraints depend more on a society’s attitude than on where you are, I think, so they could be even freer aboard a starship than many Earthbound societies. Except about such things as blowing holes in the hull or polluting the atmosphere. Many things we do on Earth would seem unthinkable to starship inhabitants.

But what people really fail to recognize is that we tend to accept the environment we are born into as normal, with all its advantages and disadvantages. I think a generation ship’s crew really could regard life within their hull as both normal and perhaps even quite pleasant, even if us planet-dwellers could find things to lament. We may be uncomfortable with the idea of living somewhere where you can’t hop in your car and drive to the horizon. They might find the idea of a horizon equally hard to adapt to if they reach the surface of some planet. And so forth.

“People who lament about conditions within an ark fail to realize that in most ways the life will be far superior to most lives on Earth today. ”

My life is superior to most lives on Earth today, that doesn’t stop me complaining about trivialities! Telling someone that they shouldn’t complain about their life because there are six-year-old kids working in coal mines in the Congo never really seems to help.

The culture that develops in an ark will also set the blueprint for the culture of the colony that develops once planetfall occurs.

A well written piece…

Many unknowns along the way…we’d need artilects to help out…

There may be a good reason why the stars are so very far apart…

I think just getting to Alpha Centauri at one million miles an hour will require over 3,000 years… one way…I can’t imagine any human ship-born culture enduring for three thousand years…But could Aristotle have imagined flat screen television?…Maybe he could have…A crew of 1,000 might work…and a fleet of twelve ships…A lot would change in 3,000 years…Would America even be here 6,000 years from now hearing what happened when they arrived?

I agree. I think that the socio-engineering problems of getting to the stars in generation ships would/will be at least as great as the problems with the physical technology. After all, the longest any human institution has lasted so far is the twenty centuries the Catholic Church has endured, and even that grouping has changed beyond recognition several times. (Of course America won’t be here in 600 years, let alone 6,000…) By contrast, the society and the governance on board the ship will need to be absolutely rigid and unchanging – any change will spell inevitable death and failure. How this can be done, I have no idea; but I don’t think it will be ethical by our elevated standards.

I strongly disagree. That doesn’t follow at all. Rigid and unchanging structures lack the flexibility to deal with new challenges and new requirements that the voyagers will inevitably encounter. I think the only way that a generation ship’s society can remain stable is for it to be flexible enough to change and adapt to new situations. We cannot know what form of society will arrive at the distant star. We can only be sure that it will have changed dramatically from what we started with. In light of this, we should arrange a generation ship’s constitution to allow for peaceful changes to be made. To do otherwise would be to imply that the designers of the ship have the foresight to plan for everything, which is clearly utter nonsense.

The point I am trying to make is that a generation ship must contain a living, viable, self-governing culture to succeed. We are talking about a civilization in miniature, not a craft that can be run in rigid military style like a nuclear submarine. Nobody is coming back, and no one is going either because the ship will take generations to complete its voyage. It must be the home of everyone aboard it, and the goals of living a fulfilled life and continuing the mission must intersect so that each generation will responsibly care for their ship and pass it on to the generation after them. In many respects, it will not at all be unlike life on Earth.

Japan has had an emperor from a single family for far longer than 2000 years. Going back to 660 BC

Thanks! Generation ships can travel at a variety of speeds, from 10%>0.1% C depending. Anything much slower than that might be just too slow. Flights in the thousands of years are within the scope of recorded history, but are obviously outside the range of any spaceflight we have yet seriously considered. I imagine that even very, very nice humans in flawless ark-ships would have a hard time completing a mission that long! But we have thought about such trips before. Solar sail arks would take that long to reach the nearest stars.

If there is a limit on how long a starship society can endure between launch and planetfall, it would be worthwhile trying to determine this number. We can only guess, but if we know how long the ship can endure, we can figure out how far we can travel at any particular speed.

Perhaps, however, it will turn out that our Earth-based prejudices color our ideas too much. Perhaps even thousand-year voyages can be achieved in a sufficiently large ship. If that is so, we shall be able to expand our range of destinations quite a bit even with slower propulsion systems. At 0.0043 C, we can reach Alpha C in 1000 years. At the 0.12 C projected for Daedalus, we can travel a full 120 lys in a 1000 year flight, bringing a vastly greater number of stars within our reach. Remember that the volume accessible to interstellar travel goes up by the cube of the distance we can travel!

By picking a good route many stars can be reached just with little changes in direction, one starship could seed hundreds of star systems on a very long term journey, maybe AI will do this and we follow hundreds or years later.

Yes, I’ve heard of such multi-star trajectories. This might make for an interesting strategy for colonizing missions. Due to the difficulty of slowing down the entire starship at the destination with rockets, some people have proposed abandoning the main habitat and arriving in the system on a small dedicated deceleration/landing stage. This saves enormous amounts of fuel. The now defunct habitat would continue on its course and either erode away from collisions with cosmic dust or exit the galaxy – whichever comes first.

But perhaps we could instead equip the ship with multiple landing stages. When the ship flies past a destination star, a colonizing party shall leave the ship. The remaining crew will make a course correction and continue to the next promising destination, where another party may leave. Eventually, the last party will abandon the ship entirely. In this way, a single mission could colonize multiple destinations.

I’ll looking into this idea. The practicality of this concept will depend on just how massive these deceleration/landing stages must be. Carrying more of them will require more fuel. However, MIRVed starships may be much more efficient than either decelerating the entire habitat or just abandoning it. We don’t need the habitat when we wish to stop and land at a target exoplanet. It would be nice to have, but it is dead weight. But just abandoning it seems wasteful. I don’t know if anyone has ever proposed something like this before. If anyone has heard of anything like it, I’d love to hear about it! Otherwise I might have just had an original idea.

The landing stages could use magnetic sails, avoiding the need to bring propellant from Earth. These landing stages could also be aimed at asteroids and comets where habitats could be built as well planets.

A possible architecture could include a main ship based on Project Orion. After the ship attains maximum velocity, it is reoriented so that the pusher plate serves as a shield. Landing stages could be fabricated en route and use magnetic sails to decelerate.

I have thought about the deceleration of these probes or crew pods before in another post, if the ‘bus’ spacecraft passes the star it fires its engines once again. The probe/pods are ejected in the exhaust stream with the probes/pods creating a magsail around them which decelerates them in the exhaust plume. Non-organic probes can be decelerated quite heavily ~30 000 g but organic ones less so.

I dabbled a few years ago about using giant nanotubes with salt caps as housings for algae, we knit these housings on to thin nanotube sails and on passing a star they are ejected into the star systems as the main bus craft passes. The sails are slowed down by the ships exhaust which is subdued with other materials to prevent biological damage, the sails have AI that allows them to maneuverer in the star system using light from their sun to impact planets and seed them.

Maybe we are of such a pre-seeding of another alien race long gone ; )

Here’s hoping that a better way is found.

To launch such a huge enterprise would either require that the destination was an absolute “Sure Thing”, or an act of total desperation on the part of a very threatened earth. Because no more help would arrive anytime soon.

Or likely ever.

The “Where is Everybody” Fermi Paradox in itself is plenty of reason to feel uneasy about deep space travel. Even slower than light. I realize that everyone on this forum knows that if we find life in our own, rather harsh solar system, it would suggest that life in the galaxy is very common. All the more reason to wonder what the problem here is.

I’m a hopeful skeptic. But a person like me thinks “out there” is a calling that shouldn’t be resisted or denied. Climb the mountain because it’s there. The galaxy is too wonderful and too beautiful (and unfortunately too big) to be ignored.

I too hope a better way will be found. However, space is big, and even with propulsion systems thousands of times better than what we have today, it will take a long time to get anywhere. The a multigenerational approach is potentially liberating in the case that we never have warp drive (which sadly seems a likely possibility) or relativistic rockets.

Personally, I favor the Percolation Theory as an explanation of the “Fermi Paradox”. Aliens may have been spreading between the stars long, long before we ever turned our eyes to the sky, but it does not mean that their expansion will not leave gaps and voids unexplored. No wave of exploration was ever relentless in our own past. We might not notice if a civilization launched one starship, or ten, or even a hundred, and only a small fraction of the civilizations founded by those ships actually went on to launch starships of their own. All we can say is that whatever is going on out there, the probability of a planet like Earth being overtly visited during the 5000 years of human civilization is small enough that we have gotten by without being knowingly visited.

Percolation is a valid option to the paradox and I hope you are correct. However, I think we are living through one of the great filters and maybe no life form has been able to crack interstellar flight.

Since the 1960s we have been able to control fertility and rates have been coming down since then. There appears to be a direct relationship between education levels and fertility and no country has been successful in changing that dynamic and restoring fertility rates to replacement (around 2.1).

Japan, Singapore, EU and most western countries have fertility rates below 2. If this continues we will see world population falling from the end of this century and the fall could become rapid.

I find it hard to imagine large space based infrastructure being developed by a shrinking population – so I think we have at best 100 years to crack interstellar flight.

I favor a combination of the “rare earth” theory and the “just not practical” theory. Assume intelligent technological civilizations are rare in the galaxy. Also assume that all the technical and social problems described above in the discussion of Ballard’s story are very difficult to solve. Assume that warp drives, stable wormholes, and other FTL ideas just don’t work in the real world. This would explain why no aliens have ever come calling.

Except that you don’t need warp drive. Fermi observed that you could theoretically colonize the entire galaxy in a few million years, even if you never traveled faster than a small percentage of C. Since there are planets far older than Earth, this suggests that if aliens are common, some technological civilizations will be far older than Earth. With only a few million years head start, an expanding wave of colonization could in theory reach everywhere in the galaxy, no warp drives required. Thus, Fermi posed this deceptively simple question–where are they?

One obvious answer is that such an expanding wave of colonization may not infallibly reach every single star. Assume that interstellar colonization missions are slow and expensive, and they they tend to have a short maximum range (<15 lys? or some other number?). Not all such missions successfully colonize their target system, and of those systems successfully colonized, only a fraction send out further expeditions. Furthermore, not all colonies maintain forever. If this is the case, then such expansion will be more of a percolation than an unstoppable wave, and it will leave voids and gaps untouched which no one has reached. This "percolation theory" seems far more reasonable than Fermi's original assumption of an unstoppable, eternal wave.

Ironically, it is not too hard to fix Fermi's paradox if FTL is assumed. Science fiction authors naturally make up the details of their fictional stardrives, so they can set all sorts of strange limits. Perhaps Earth exists in a region of the galaxy inaccessible with standard methods of FTL, whether temporarily or permanently. Thus, everyone is too lazy to bother exploring our region of the galaxy because they are spoiled by the rapid travel afforded by hyperdrive or whatever. Have the action begin when humans reach a planet in the FTL-accessible portion of the galaxy and run smack-on into an alien empire or when the "hyperspace disruption" or whatever ceases and Earth becomes accessible. Or perhaps humans invent an unknown form of FTL that works in our portion of the universe and then run smack-on into the ancient empire once we travel outside our formerly inaccessible void. Pure space opera, of course, but it raises some interesting ideas.

Perhaps Earth has not been visited simply because we live in a region of the galaxy that is harder to reach using standard forms of galactic travel? Aliens may not bother going places that are hard for them to reach when more accessible star systems are available. One candidate for such a "galactic doldrum" (and this is pure speculation) might be the Local Bubble. The region of the galaxy we inhabit has neutral-hydrogen density of one-tenth the Milky Way's average ISM. If aliens use hydrogen ramjets, they may avoid such low-density regions. I'd love to run the numbers on this sometime and see how the density of the ISM affects the hypothetical performance of a ramjet (though, of course, ramjets have many difficulties to begin with). BTW, I am not going to christen this concept the "Galactic Doldrums" theory, unless someone has named it already. *grin*

On the other hand, low density regions could be helpful for exploration if you aren't looking to sweep up free fuel. At relativistic speeds, hydrogen atoms become an annoying flow of head-on cosmic rays. These can be shielded against, but the lower density of the ISM in the Local Bubble may favor exploration (though, this is the opposite of a galactic doldrums). But what about other particles? Even grains of dust can do quite a bit of damage at interstellar cruising speeds, and even a small meteoroid could be instantly fatal.

We don't yet know the size spectrum of interstellar matter between micron-sized dust grains and small stars in interstellar space, so far as I know. But if space is full of ice globules and other such debris, I can imagine the situation becoming precarious for interstellar travelers. Even if such impacts are rare, a single one could be deadly. Hopefully they will be very rare. But how might the density of interstellar matter vary from one part of the galaxy to another? Maybe aliens tend to turn back when they encounter areas of the ISM that are "filthier" than others, especially if they have developed relativistic travel and are unwilling to revert to slower methods of travel. Just some speculation, but it should be quite interesting to examine the assumption that all parts of the galaxy are equally accessible to advanced ETI, especially since the danger posed by impacts goes up the faster you travel.

It is also interesting to note that improved technology might in some cases limit the range of advanced starfaring aliens. Star-rammers may avoid voids like the Local Bubble, while future human relativistic rockets might consider the void an advantage- but perhaps nobody outside of our galactic boondocks would ever go back to the terrible mass ratios inflicted by such primitive technology as photon rockets. This may turn the direction of alien exploration away from Earth. Of course, we should look a lot longer and harder before we arrive at the conclusion that no starships have ever visited our vicinity!

We don’t know for sure that no aliens have ever come calling. We only know that possibility has never been officially recognized by those in charge. There are some in government and military circles who have quietly suggested they do exist and that the government hides that.

I favor what I call Tripartite Solution to the “Fermi Paradox.” This tripartite explanation is as follows: (i) life in the Universe faces enormous bottlenecks at each of the major transitions along the way to intelligent technological civilization, (ii) deep space travel and colonization are extremely difficult even for the handful of technological civilizations that even bother to embark on it in the first place, and (iii) FTL travel and/or communication violates physical law.

For all we know, the emergence of life from non-living matter may be a very rare chemical fluke, according to astrophysicist Paul Davies. Though I suspect Davies may take things to the extreme when he mentions in his book “The Eerie Silence” that he would not be surprised if the only life (period!) in the observable Universe is on Earth (maybe also Mars through interplanetary exchange), it could still be that the emergence of life from non-life only occurs, say, in 1 out of 1,000 large galaxies. Once life emerges, it also possible that the transition from unicellular life to multicellular life may be quite difficult such that this transition only occurs in 1 out of every 1 million galaxies. In turn, intelligent technological life may only occur in, say, 1 out of every 1 billion large galaxies. To keep the math simple, let’s assume that there are 100 billion large galaxies within the observable Universe; so, this would mean that there are only ~100 technological civilizations in the entire observable Universe each of which is separated by billions of light years. Once this level of scarcity is reached, the distances between islands of living matter—let alone intelligent matter—become so vast that detection becomes almost inconceivable unless some version of FTL travel and/or communication becomes possible; however, part (iii) assumes that FTL travel and/or communication violates physical law and is therefore impossible. These distances negate counterarguments that “all it would take is 1 civilization to colonize the entire Milky Way galaxy.” Well, if the nearest technological civilization, which mind you, may not even be space-faring in the first place is 3 billion light years away, then this substantially weakens the argument that “one of them could have done it and therefore we would have seen them by now.” I am not saying this is how things are in the real Universe, but the Tripartite Solution is among the most plausible solutions to the Fermi Paradox that I have come across.

I doubt they would be alone, although the receiver on the craft will remain the same the transmitter can get bigger and bigger over time in the home system allowing enormous amounts of data transmission. As for the volume of the craft that would be down to the mass-energy budget available, an O’Neil cylinder is limit to its diameter of about 7km but not limited to its length. I suppose we could design the craft so not all of it is available to see at the same time allowing a sense of exploration. I also doubt it will be boring, there is much to see in space, more exoplanet transits are available as time goes on allowing astronomy to go on. If telescopes are placed on the 7 km diameter edge or along the length it would allow great resolving power and allow a view of their future and home worlds Sun’s.

You are quite right, this is something I have been thinking about a lot myself. An interstellar mission does not have to be boring. From the standpoint of astronomy, the ship is an excellent platform from which to observe the universe, and many unique observations can be made from there. It may get quite close to passing stars, enabling detailed observations of conditions there. The craft is an excellent platform from which to observe the interstellar medium. I had not thought about how the ship’s moving vantage point will bring more exoplanet transits into view. That’s a very interesting point, and an excellent opportunity for the starship’s inhabitants to take advantage of.

Another interesting point – as the starship gets further and further from Earth, it will provide a longer and longer baseline for trigonometric parallax measurements of the distance to faraway stars. The inhabitants may pass the time on their long voyage mapping the universe to an ever-greater precision for the pioneers who will someday travel even deeper into the galaxy.

Perhaps the starship will get close enough to some stars to allow the crew to use more direct methods of exploration. If they have the mass to spare, the inhabitants could dispatch flyby probes to investigate passing star systems. Who knows? Perhaps a generation ship can have its own robotic space program!

The assumption here is small crew small spacecraft,

I prefer O,Niel or Rama sized wordlets with large crews and much longer travel times, as a back up this starship would also have AI and stored germplasm.But the first attempt would have a living ecosystem inside the rotating cylinder.Most likely a democratic university town with extensive forests.The cylinder walls would have refugiums in event of inability to maintain the ecosystem , this after all is close to the Rama idea.

Yes, “Thirteen to Centaurus” has many assumptions that don’t hold up when you examine them. Trading off speed for luxury and endurance is an interesting idea. We tend to think in terms of shortening the voyage as much as possible, but perhaps a slower worldship will be much easier to live on than a faster, less massive, and more spartan “sprinter” craft. If the voyage is already longer than a human lifetime, who cares about speed if it comes at the cost of comfort and safety? Perhaps we could even have the craft latch onto a small KBO, light up its engines for a slow passage to Centaurus, and mine the object for needed elements, fusion fuel, and remass on the voyage.

They will unlikely use a KBO for on-route fueling as the object is firstly not moving very fast and secondly it is in orbit about the Sun and unlikely to be going in the same direction as your spacecraft is. They could use it as a jump off point though using the fuel in the object and the materials to build the starship.

If anything, life aboard a world ship might be more fullfilling than here on earth. People will know their work counts for something, keeping the ship alive. For any hobbies, or personal interests, the opportunities would be just as great as here on earth in most aspects. A little less in some, say oceanography, while more if your interest is studying interstellar space. I would expect things like painting, gardening, and even rock climbling, to be possible hobbies in a world ship.

As for living space: I would expect personal space to quite luxorious, while public space might be rather less than what we’re used to. After all, in a world ship there shouldn’t be any reason you can’t build as high as you want, even to the far side of the ship, and fill it with living space. People would be able to modify their personal space to suite their tastes as often as they wished, and interior decorator would be a promising career.

Want to go diving, then you can in one of the water reserves that’s filled with kelp, shellfish, …. Want to go flying? Well you can do that as well, just rent a set of wings, unless you own your own, and find a low-g part of the ship.

Kid: Mommy, I want to go flying like they do in space.

Mommy: You can’t do that on earth honey.

Kid: That stinks.

I doubt that it’s going to be like that. It’ll be more like living in a lot of small metal rooms with safety doors between them. The danger of collision with even a very small grain of dust is very great at such high speeds. And of course luxury will be non-existent, because mass will be at a premium. All capacity that is not absolutely essential for the functioning of the craft will be taken up either for spare parts or for items that will be needed at the destination, such as farming equipment (or weapons).

I doubt that that will be the case. Collisions with even small pieces of debris can do damage, but Gerard O’Niell and his team showed that it would take days for the air to leak out of something like an Island 3 colony. There would be plenty of time to plug the hole. Also, I would expect such a ship to put some consideration into shielding.

I don’t see any “of course” about it. Even on modern spacecraft, astronauts are allowed to bring low-mass personal items and so forth. Even if we must make do with much less space and material than people are accustomed to on Earth, we can find more efficient ways to use what we have. I am sure that there will be some luxuries available on a ship that is designed to be the home of generations of people. And, honestly, luxuries will prove to be as essential for crew performance as any tool. It is weapons that will be (hopefully!) useless on a generation ship – the crew will not have anyone to use them on but each other!!

In the long run, I suspect that it may be wiser to build a larger, more massive, and slower ship than a faster but more spartan one. Having plenty of room, extra resources, and a larger population will make it easier to survive the journey. Collisions will still be a potential problem even at more sedate speeds, but we could put some of our extra mass into sufficient shielding. Endurance might trump sheer speed on a long journey.

Shielding will be a minor problem, there are active systems like lasers, ion beams and internal conduit mechanisms to remove dust/gas. There are also passive systems such as electrostatic, magnetic systems and physical shielding (stand off/nanotube deflection) to name a few.

While these are ideas are plausible, they require a quantum leap in technology. Anyone who has ever spent time on a submarine or on the ISS will tell you that living in a confined space with a recycled atmosphere is not luxurious, in fact it’s quite spartan.

Yes, everything we are discussing here requires incredible advances in space technology. However, judging the plausibility of a luxurious environment on a generation ship by the standards of the ISS is a bit like vikings discussing the future of ocean travel based on their experience in open longboats. The luxury represented by an ocean liner the the QE2 would have been utterly unimaginable to them.

Personally, I could never comdemn my children to life aboard a generation ship… Nor my grand children, and their children , or theirs… On infinitum… It would be an unending job rather than a life, and theyd never see the completion of the mission. Its something they would never have had the choice to sign up for… And as such , they would be equivalent to galley slaves, or shanghaied sailors. The worst thing is they could never have the choice of going back to earth. There has to be a better way… Hibernation, light speed propulsion…

We are already aboard a generation ship completing a lonely circuit 150 million kilometers from the sun– the Earth!! If life on board the starship offers the crew plenty of opportunity to live a full life, they can be happy aboard one just as we are on this planet. You speak of their life as being “an unending job” but that need not be so. There will be opportunity for all activities on a generation ship, not just work.

I would very much like for us to find a better way to travel between the stars than arkships. However, nature has no obligation to live up to our desires. We might be confined to slow methods of propulsion for a very long time to come. In that case, we won’t get to the stars by idly wishing for a breakthrough right out of space opera.

The situation for such a crew will be a lot worse than the situation for old-time galley slaves or shanghaied sailors, because there will be absolutely no prospect of escape.

Not really true.

Don’t think of a generation ship as a ship. Think of it as a colony that happens to be traveling. A reasonable sized comet would have enough resources to support many thousands of people in comfort for tens of thousands of years.

So, imagine that people start colonizing comets. Eventually somebody is going to decide that they’d rather not hang around the Solar system, and light off a fusion rocket at one end. Doesn’t change the lifestyle of the colonists much at all; Physical visits would have been rare, and communications with the solar system will still be feasible. A group of such colonies might settle on the same destination, and travel in formation.

Occasionally your comet colony will pass other objects in the Kuiper belt, and beyond. At those times, the colony might split, sending off it’s own colonies. That constitutes escape, doesn’t it?

In the mean time, where’s the escape from Earth? So, are we that better off.

Really fast ships would solve a whole lot of problems… go fast enough and time dilation on board would make the time spent a lot shorter…

As for hibernation systems, I cant believe that you could build automated machinery that would function for a thousand years… How could you even test such a system? Would you happily climb into one? Not me…

And, Im sorry, but you couldnt genetically modify humans to be submissive and peaceful… Nor would most people today allow such a thing… Nor would you want to… I mean, what exactly is the purpose of this project anyway? Would they re-engineer their children’s DNA back to the original pattern once they got there?

Religious sects arent any guarantee of social stabilty either… Its quite common for members of amish or hutterite comunities to leave the “fold.”

To be fair, the closest analogue i can see to a generation ship would be an island culture like Hawaii… The only difference is they never had to maintain life support systems…

The down side is an example like the easter island culture which destroyed itself with warfare and environmental damage. The RapaNui are estimated to have arrived between 300 and 1200 … They were in really bad shape by the 1800s … So there’s an example of a “generation ship” with a totally automated life support system and a singular social culture and it still failed… I guess the moral lesson is dont waste your time and resources building giant stone heads…

Don’t waste your time and resources building giant stone heads? That should be written down somewhere in the generation ship’s manual of instructions! *laughs* Though I have no idea where they would get the stone for it.

On a more serious note, we can be sure that there will be casualties when we send out real starships. It is simply unavoidable. From ecological catastrophe to civil war to collisions with cosmic debris, real generation ships will have to survive numerous dangers on a trip to another sun. Some of them will be unlucky. We can’t guarantee safety against all hazards, no matter how hard we try. Whatever cultures take to star travel, we can be sure they will not be risk-adverse.

I will point out that the Earth is not secure against all hazards on long time frames either. We can’t avoid danger by staying in the cradle and pulling the blanket over our heads, hoping that the universe will stay out.

Let’s get the first successful BioDome experiment under our belts first, shall we?

Yes, that’s an obvious requirement. We must try out the concept of a sealed and unescapable human environment exhaustively in a sealed space environment first, for centuries, before going to all the expense of launching it towards a star. Probably we should try out a number of differently-organized such environments, in parallel, to see which has a chance of working over the long term. I don’t think this is going to be practical under the good old American system of freedom and ethics. The research can’t even be started except under a totalitarian system that is tougher than anything known in human history.

The Out of the Unknown episode of “Thirteen to Centaurus” can be viewed here:

http://www.dailymotion.com/video/xxsxps_out-of-the-unknown-thirteen-to-centaurus-s1-ep11_shortfilms

The US production “Ascension” had a similar theme – a worldship launched in the 1960’s – albeit with different motives.

Ascension is available- either Amazon or Netflix as I recall.

An author should be free to argue any premise. I never read the Ballard story and I know he was a pessimist, but I would like to comment about his basic premise that attempts at in-system space colonies failed and so research towards interstellar colonization faded away. Could nobody in the future Ballard predicted come up with a way to make a buck out of tourists touring a lunar research outpost like the one now operating at the South Pole, NEO mining, rich honeymooners orbiting around the moon? No political or religious extremists wanting to colonize Mars to get away from the rest of us? Just a reasonable decrease in launch costs per pound (like air-breathing reusable first stages?) and transit times from Earth orbit to Mars would open many options to make space colonization much more reasonable. Also, modern technology will soon be able to generate images of nearby Goldilocks planets and that would be enough to energize future adventurers. So, sorry, Ballard, although I’m happy for you that the story sold and the check cashed.

“Also, modern technology will soon be able to generate images of nearby Goldilocks planets and that would be enough to energize future adventurers. ”

That indeed seems to me a very big game changer, consequences of which are underestimated.

If we get photos of planets with visible biosphere cover, it will immensely inspire people and nations to get there.

Yes, this is why our current research into exoplanets is regularly covered on these pages. I don’t think we would ever bother developing interstellar travel if there were no planets to go visit. Even if we are content to build a space-based civilization around another star, we still need at least a debris belt of some kind. We aren’t as interested in other stars as we are in the objects orbiting them.

Fortunately for us, our space telescopes have revealed that planetary systems are the norm. This may have been the turning point for interstellar travel. Discovering a planet with an actual biosphere will be the spark that really ignites public interest in interstellar exploration.

It isn’t just worldships that will be relatively isolated – habitats in the outer solar system will be relatively small and self-sufficient. Communication delays will make interaction with the rest of humanity a relatively slow process, rather like pre-telegraph earth.

I would expect these habitats to be quite large, certainly with village sized populations at a minimum.

I think they will be quite pleasant places to live, much like living on an island like Bermuda. Most people will be happy, but a few will get the space equivalent of “island fever”.

And long before we set out for the stars, we will have had at least some experience with isolated space habitats. There will be crucial differences, however. A solar system habitat can rely on solar energy and expect rescue efforts from other habitats and Earth if something goes wrong. The further out the habitat goes, the more isolated it will be, but the initial Island 1’s and 2’s in Earth orbit will be very close to support.

The crew of a starship will be utterly isolated. Their friends back in the solar system won’t be able to do much more than send sympathetic radio messages, and not even that once the light speed delays become long. So while a generation ship is a bit like a mobile O’niell colony, there are some big difference for the inhabitants. There is some good sense behind sending not one but multiple starships that can support each other.

Will the crew of a generational starship be “utterly isolated” ? Communication between Earth and a generational ship at relativistic speed would still be possible and I think very important in maximizing the chance of success for a generational ship. The shrinking bandwidth and increasing time delay would make small talk impossible but not information like Netflix, breakthroughs in medicine and astronomy. You mentioned using the starship as an observational platform for astronomy. Imagine how fulfilling it would be for crew members to share and receive feedback on their observations with astronomers on Earth.

I remember reading James G. Ballard’s “Thirteen to Centaurus” with my head shaking through most of it. The crew was subjected to unrealistic levels of isolation that lowered the chance for success.

Alastair Reynolds in his “Revelation Space” saga has copies of people sent to interstellar ships where their simulations provide advice.

Such simulated copies of personalities(not real AI) could provide entertainment and advice to the crew.

In “The Dark Beyond the Stars” by Frank Robinson, the crew also uses VR , in which it is actually immersed all the time, making up for the drab and grey environment they are in after eons of travel(it is augmented reality type of thing among others, so their surroundings look much better and are filled with fantasy objects).

The crew of the starship will be utterly isolated from direct physical support. You are right that communication will still be possible. Indeed, sending astronomical information back and receiving feedback is a great idea! This means that the starship crew can still maintain a meaningful connection with Earth. The round-trip time will grow more and more as the starship moves away from Earth, however.

I agree regarding Ballard’s story. I mainly used it as a springboard for tackling these issues. The level of isolation in the Station was entirely unrealistic.

I think you underestimate the distances involved, even within the solar system. A solar system habitat out beyond Mars would very likely have no expectation of fruitful rescue efforts should some major catastrophe strike. Unless of course the habitats in remote regions tended to exist in clusters rather than as individuals. Come to think of it, a fleet of ships traveling on an interstellar journey would mitigate pretty much all of the problems you (and others) are positing for a single ship.

And by the time the capability to launch such ships is available, we should see such deep-space habitats as viable places to live your life. Don’t expect the interstellar ships to be populated by people from Earth; they won’t have the proper psychological makeup. Instead, the colonists are much more likely to come from the deep-space habitats. Heck, it might be that one or more of those habitats would decide to reconfigure and launch itself as an interstellar mission. Problem solved!

Multiple starships will give not only redundancy in case of failure but also a wide baseline for communications and will make a great observational baseline, imaging a baseline of hundreds of thousands of km’s across.

There is also the possibility of you been ‘reborn’ i.e. when you die your genetic component is reconceived and you start again, your memories will have died but not you in a sense. We could save memories digitally for your later amusement. I and I believe others would more likely be sent on a long trip if we know we can be restarted again and again. We could remove defective genetic components that happened as you aged so in a sense you become better.

That’s not being reborn, that is having a clone made. By that argument, identical twins are actually the same person! A crew of clones would not be very helpful. That would bring evolutionary adaption to a halt. Also, we want more genetic diversity on a starship, not recycling of old genetic material.

I would far prefer that my descendants get the opportunity to be their own individuals than to insist generations of clones must act like they are me to give me some futile sense of immortality.

And what is wrong with a clone, does it make you worth less than the original, are you clonist! you will not be a robot and you will be the only clone at a given time. The original crew would be very diverse to start with and the ‘remakes’ would be more likely to have the same traits as the original.

‘I would far prefer that my descendants get the opportunity to be their own individuals than to insist generations of clones must act like they are me to give me some futile sense of immortality.’

It is only for the trip, when they make planet fall they could halt it or go on as a prize for making the long trip. You have to incentivise the one way trip, ‘remaking’ is one way of doing it, I would do it, would any others?

Even though habitats with our solar system would be able to receive assistance from Earth, the cost of providing assistance would promote ever more rigorous self-sufficiency. Every generation born and raised in habitats would select for social contracts better suited for closed, self-sufficient societies.

I don’t think the social contract is subject to the law of natural evolution. It would be best to establish the right social contract for the trip, in the first place. And I think it will be a very rigid one.

Individual humans and groups of humans have been applying selective pressure on social contracts since there have been…well, humans. The social contract of a closed habitat will be more rigid than one found in modern societies, but I don’t think it would reach “very rigid” unless there were personalities on board that chose to make it is so and had the power to enforce their will.

This is not selective pressure. You don’t have various social contracts competing with one another and producing various numbers of offspring, with the type that has the most surviving offspring coming to the fore. Social contracts among humans continually change and improve (or worsen), yes, but this is not evolution by selection.

I disagree. When I look at the history of the collection of laws and cultural norms described by the term “social contract”, I see meme theory at work.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meme

I agree that various memes may “compete” within one society that has a single social contract, and this may be likened to Darwinian evolution in some sense. But there is only one social contract at a time in a single society, and social contracts don’t compete with one another within one society. It may be analogically said that memes compete with one another within the environment which is the social contract, and that the winning memes modify the social contract. A bit like the various amendments to the US Constitution. But personally I think that this analogy is stretched too far.

For any given contractual society, there are as many copies of the social contract as there are citizens and citizen analogs such as corporations. Competition occurs whenever those copies vote, practice unlawful and lawful behavior, protest, revolt, litigate, legislate, etc.

The fidelity of the analog can certainly be argued.

Allow me to clarify one point. Shorter transit times to Mars by whatever method of propulsion one chooses would reduce the chances of effects of solar flares and cosmic ray exposure. An electromagnetic shielding system to deflect charged particles would also be helpful.

As an interesting side note, 95% of the 10 million metric ton mass of a Stanford Torus is devoted to the radiation shield. Which is just dirt. Lunar regolith, to be precise, but still dirt. I must admit that the idea of hauling 19 times again your basic structural mass in dirt is rather galling if you are a starship designer. It makes the idea of an electromagnetic “deflector shield” incredibly desirable! There are some ideas in this direction, but nothing has been tested yet.

On the other hand, shielding mass becomes more and more efficient the larger your habitat becomes. The cube-square law work in our favor, and eventually the sheer mass of the habitat is enough to protect you.

An Island 3 colony would require no extra shielding, since the mass of the hull and the air, soil, and water contained within would be quite enough to shield you against cosmic rays. That’s another argument for a big ship.

I see magnetic shielding as a very viable technology to protect crews, remember the amount of energy in the solar wind is 10 000 time weaker than the energy from sunlight, so converting the light into a magnetic field is very productive.

Next problem–as in Orphans of the Sky–how do you convince people who have lived the last three or more generations on a ship, to leave? Or to get dirty with some alien biosphere at the bottom of an oppressive gravity well? At best maybe they’ll say–“Look at all these cool asteroids we can make new habitats out of!”

I agree Tom. I still believe the destinations of choice will be clusters of young hot stars that haven’t been swept out yet.

Dusty regions will need to be avoided as there is an increased chance of impacts which could prove disastrous.