One of the great missions for the 21st century could be FOCAL — a space probe sent to the Sun’s gravity lens some 550 AU out. Gravitational lensing is becoming a major tool for astronomers, and we’ve even seen planetary detections using microlensing, looking at targets in the direction of galactic center and the faint changes in light that indicate a planet’s passage. The gravity lens concept, harking back to a 1936 Einstein paper, came to the fore in 1978, when Dennis Walsh and team spotted a twin quasar image, the result of the lensing caused by an intervening galaxy as it bends light around it.

So we know that lensing works. As far as I know, the first person to apply the notion to spacecraft was Von Eshleman (Stanford University), who considered a space probe to 550 AU to exploit the potential magnifications available there. And such missions have also been considered, by Frank Drake among others, as SETI experiments, using the Sun’s ability to magnify the hydrogen line at 1420 MHz, the so-called ‘waterhole’ frequency for interstellar communications.

But no one has put more thought into a FOCAL mission than Claudio Maccone. The Italian physicist led a 1992 conference that investigated mission concepts, and submitted a proposal to the European Space Agency the following year. Since then, he has followed up this work with a series of papers in Acta Astronautica and the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society, investigating among other things the uses of the gravity lens for cosmology (detailed imaging of a small slice of sky to study the cosmic microwave background), communications (using gravity lenses around nearby stars to boost signals from interstellar probes) and astronomy. His 1997 book The Sun As a Gravitational Lens: Proposed Space Missions (Colorado Springs: IPI Press) is an exhaustive analysis of the topic now in its 3rd edition.

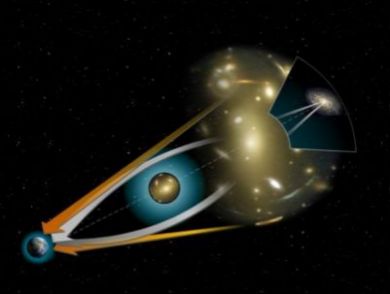

Image: Gravitational lensing at work. A space probe at 550 AU and beyond could exploit such effects to make detailed studies of other solar systems, among numerous other scientific targets. Credit: Martin Kornmesser & Lars Lindberg Christensen, ST-ECF.

In a presentation he will make today at the New Trends in Astrodynamics and Applications conference in Princeton, Maccone notes that the use of stars as gravitational lenses is a logical next step for astronomers. “As each civilization becomes more knowledgeable, they will recognize, as we now have recognized, that each civilization has been given a single great gift: a lens of such power that no reasonable technology could ever duplicate or surpass its power. This lens is the civilization’s star. In our case, our Sun.”

A fascinating aspect of the Sun’s gravity lens is that we do not need to park a spacecraft at 550 AU to utilize it. As the spacecraft pushes past this distance, effects created by the Sun’s corona diminish and imaging only becomes better. We have an opportunity to see images the likes of which could not be produced by ground-based or conventional space-based telescopes, assuming we can find a way to propel a spacecraft to the needed distance in a reasonable amount of time.

If we try to sketch out a rational pattern for exploration beyond Pluto, FOCAL should be front and center in our thinking. New Horizons reaches the Pluto/Charon system in 2015. After that there is active work on Innovative Interstellar Explorer, a probe that would carry instrumentation beyond the heliosphere and become the first mission specifically targeting the interstellar medium. A well-equipped FOCAL probe, driven perhaps by solar sail with close solar flyby, is a logical goal after IIE or as part of a combined mission concept.

But such a mission, the groundbreaker for space-based gravity lens studies, would be the first of many. In particular, as we learn to push spacecraft to truly interstellar speeds, FOCAL becomes a needed precursor that can tell us much about target solar systems. As Maccone notes in The Sun As a Gravitational Lens:

I anticipate that there will be a host of FOCAL space missions launched in all directions around the Sun, each probe launched in the direction exactly opposite to the star to explore with respect to the Sun position….A FOCAL space mission could be used to magnify anything of interest outside the Solar System. One should then say that FOCAL will be used to magnify the nearby planetary systems, meaning not just the nearby stars themselves, but also their planets, halo disks, Oort clouds, etc.

The range of targets is vast if FOCAL-style missions become routine through breakthroughs in our propulsion technologies. In the interim, deep space probes to the required distances offer the possibility of numerous scientific investigations, many of which were first examined by NASA in its studies for the TAU (Thousand Astronomical Units) mission in the 1980s. What Maccone continues to argue forcefully is that any probe into regions beyond the heliosphere will be in position to exploit the gravity lens, and that our designs for such probes should incorporate the needed instrumentation to show us how best to use this tremendous natural tool.

Can anyone post some figures about this ?

For example, what is the resolution obtainable ? What is the width of the field ?

Is it fixed ? Can we have both narrow and wide field images ?

I keep hearing about how good such telescope would be but never any precise figures.

I mean it has to be fantastically better than anything we could possibly buid to be worthwhile. This thing has two bad disadvantages :

1) It works from 500-1000 AU (I heard different distances before)

2) It will look in a fixed direction (more or less, stearing is VERY slow).

It has to be REALLY good to overcome 1) and 2).

Enzo

Enzo, one comment: The distance is 550 AU as a minimum, with continuing use of the instrument after that. There is no upper limit on the distance for FOCAL because, unlike the case with optical lenses, the gravity-focused radiation stays on the focal axis after 550 AU. In other words, the focal line extends to infinity. The disadvantage of the distance is offset by the fact that this proposed observing platform can do things no other telescope could handle. Ponder this, from Gregory Matloff’s Deep Space Probes book: For a FOCAL mission at the gravity lens, EM radiation from the occulted object is amplified by a factor of 108.

Both Matloff and Claudio Maccone have given analyses of the concept and the mathematical description of the lens is exhaustively presented by Maccone in his The Sun As a Gravitational Lens book (which compiles earlier papers). What I’d like to do to continue exploring the concept is to bring Dr. Maccone in for a comment on your questions above, and if that is possible, I’ll post that material as soon as it becomes available.

I guess there has to be a practical upper limit for the distance, otherwise we could use any other star, like Alpha Centauri, instead of travelling all the way to 550 AU, right ?

I’m looking forward to more detailed informations from Maccone.

Enzo

It’s a pity we don’t have any white dwarf stars nearby… I calculate that for Van Maanen’s star, the key radius is a mere 0.13 AU. A neutron star would presumably be even easier to use as a lens, but I suspect you won’t find many of those in systems with indigenous civilisations.

Hi, all

I wrote an essay on the FOCAL concept last year, for the Swinburne

Astronomy Online course (http://astronomy.swin.edu.au/sao/).

I’ve just put it up on

http://jarburns.webprophets.net.au/P86-HET610-JonathanBurns.pdf

It badly needs a second release, with clearer explanations of the

numbers, and the Open Office/PDF typography is buggy; but on a

quick re-reading, I’ll stand by it.

Enzo says:

> Can anyone post some figures about this ?

> For example, what is the resolution obtainable ?

In a nutshell, the same resolution we could obtain for bodies

orbiting close to the Sun, if we were observing them from

550 AU away, or further.

This is the key to the whole concept. Imagine a cylinder of

lightrays, all parallel, and all just skimming the Sun’s surface.

The Sun’s gravitational deflection brings all these rays to a

point at 548 AU.

Assume that we have a telescope situated at 548 AU, pointed

back at the Sun. In the telescope image, an object a few

Solar diameters to the side of the Sun will be diminished in

perspective as usual – subtending an angle (object size /

distance, in radians). The further away, the smaller.

But an object exactly on the cylinder (which we would see

coinciding with the Sun’s boundary in the image) _would not

be diminished in perspective at all_. Suppose a distant

planet, say 100 lightyears away, crossed the surface of the

cylinder. Normally, its cross-section would subtend the

angle (diameter / 100 ly). But its image in our telescope would

subtend (diameter / 548 AU). (!!!) That’s the appeal of FOCAL.

To plug some figures in. At 548 AU, the Sun subtends

(696000 / (149598000 * 548)) * 3600 * (180 / 3.14159)

= 1.751 arc seconds

While Mercury subtends

(4878 / (149598000 * 548)) * 3600 * (180 / 3.14159)

= 0.012 arc seconds

The resolution of the Hubble Wide Field Planetary Camera is

0.007 arc seconds. So it could just make out Mercury at the

Solar Focal Distance. But in principle, it could resolve a planet

the size of Mercury at any distance whatsoever.

You’d have to be pointing at it just right; in fact, you would

have to arrange it so that thesurface of the “cylinder”, the

width of the Sun, just managed to cross over it. Imagine

manoeuvring the telescope, so that the cylinder approaches

this planet; as it does, its image swells from its normal

size, far below resolution, to this just-resolvable 0.012 a-s.

Another catch: if our scope is at 548 AU, then the cylinder

coincides with the disk of the Sun, so of course any object

fainter than a star would be drowned in the Sun’s own

radiation. But it gets better as we move out beyond this

minimum distance, because the Solar disk diminishes

as distance^(-1), but the width of the cylinder diminishes

as distance^(-1/2). Out around 700 AU for instance, the

Sun subtends 1.371 a-s, while the cylinder is 1.549 a-s

across.

> What is the width of the field ?

It’s on the order of the cylinder’s width: 1.751 a-s, falling with

distance. The angular magnification of the image falls off

rapidly as with departure from the cylinder, so the image is

extremely distorted. It is probably reasonable to give the

width of field as 10% of the cylinder width. In other words,

very narrow indeed.

> Is it fixed ? Can we have both narrow and wide field images ?

Only narrow. We can shift the telescope laterally, to scan our

cylinder across a wider field, but we can only budget for so

much velocity change in the observational phase, so shifting

is limited.

> I keep hearing about how good such telescope would be

> but never any precise figures.

> I mean it has to be fantastically better than anything we

> could possibly build to be worthwhile. This thing has two

> bad disadvantages :

> 1) It works from 500-1000 AU (I heard different distances before)

548 AU, and up. But probably becoming practical only around

600 or more.

> 2) It will look in a fixed direction (more or less, stearing is

> VERY slow).

Yes, exactly.

> It has to be REALLY good to overcome 1) and 2).

It depends on what we want to observe. We can have a beam

the width of the Sun or more, with resolution of milli-arcseconds,

which effectively brings its target up to 550-1000 AU.

Would we like a close look at Betelgeuse, a red giant nearing

the end of its hydrogen-burning life? How about Eta Carinae,

or Sirius B? The accretion disk of Cygnus X-1 … or the black

hole itself?

Andy:

> It’s a pity we don’t have any white dwarf stars nearby…

> I calculate that for Van Maanen’s star, the key radius is

> a mere 0.13 AU.

It would be a very interesting exercise to work out realistically

what we could do with Sirius B.

Would it be possible to use the Earth as a gravitational lens? The Earth’s gravity well certainly is much smaller, so the proportional distance would have to increase, but the Earth is much smaller, so it could still be significantly closer than 550 AU. What sort of distance would be necessary to use the Earth as a gravitational lens? What about some of the other nearby planets, specifically Jupiter?

The main reason I’m wondering is it seems like a smaller probe to test out gravitational lensing with some of the closer local objects, such as our own planet or Jupiter, in addition to still being useful for imaging, would be a very valuable way to get experience with this technique.

The distance for Earth is over 15000 AU. Jupiter is around 6000 AU. Not really worth it.

looking inversely the idea..

the microlensing that astronomers study is based on the same principle?, i mean could we detect here on earth, earth sized planets situated at 6000 AU with todays technology?

Yes, microlensing is based on the same principle discussed here, using the effects gravity produces on light, although in the case of microlensing for planetary detections, the planet is found around a star in the direction of galaxy center (to provide the greatest opportunity for lensing because of the sheer number of stars) and is based on how the star and its planet affect the light of a more distant object. In other words, we are examining the lensed image as a way of showing us something about the intervening objects.

October 14, 2006

Why not use Neptune’s gravitational lens to focus the Sun’s energy to power an intersteller mission. Not only would the light be brighter than the Sun’s surface, it would vaporize any interstellar particles and clear a path for the spacecraft. Jupiter would be even better, but it orbits the Sun too quickly.

One problem with gravitational lenses is that you have to place the spacecraft in just the right position to take advantage of them. A moving Neptune, for example, would have a gravity focus that couldn’t be ‘aimed’ at a particular destination, nor would its mass be sufficient to provide the kind of concentrated light that a power station in close solar orbit could pump through an outer system lens of the sort Robert Forward writes about.

But for astronomical observations, gravitational lenses hold huge promise, especially if we can learn to exploit the Sun’s lens with an actual mission. The trick is getting out there, of course; we’re talking about 550 AU and beyond!

Are you familiar with the September 8, 2006 article in New Scientist about Roger Shawyer’s em drive? The superconducting version could produce more than a one g of acceleration, if there was sufficient energy. Even if one had to travel 6000 AU to Jupiter’s focal point and travel in a spiral path, could one approach the speed of light? Then one could use a binary star system for energy. Sirius B eclipses Sirius A, even though both stars are about 20 AU apart. What interests me the most is travelling to the future, not the stars.

Yes, several people sent the Shawyer article and I’ve been wanting to write about it — sorry about being so slow. I suppose the beauty of traveling to the future is that the one way we know how it could be done quickly is by traveling at relativistic speeds. And that also provides interstellar travel options — an interesting journey indeed!

I can not figure out why the Sun does not focus its own light, but it can not, since the Sun’s light would become vastly brighter in all directions more than 550 AU from the Sun. In any case might one use the Sun to focus the Sun’s corona for interstellar voyages?

Mesolensing Explorations of Nearby Masses: From Planets to Black Holes

Authors: R. Di Stefano

(Submitted on 20 Dec 2007)

Abstract: Nearby masses can have a high probability of lensing stars in a distant background field. High-probability lensing, or mesolensing, can therefore be used to dramatically increase our knowledge of dark and dim objects in the solar neighborhood, where it can discover and study members of the local dark population (free-floating planets, low-mass dwarfs, white dwarfs, neutron stars, and stellar mass black holes).

We can measure the mass and transverse velocity of those objects discovered (or already known), and determine whether or not they are in binaries with dim companions. We explore these and other applications of mesolensing, including the study of forms of matter that have been hypothesized but not discovered, such as intermediate-mass black holes, dark matter objects free-streaming through the Galactic disk, and planets in the outermost regions of the solar system.

In each case we discuss the feasibility of deriving results based on present-day monitoring systems, and also consider the vistas that will open with the advent of all-sky monitoring in the era of the Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System (Pan-STARRS), and the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST).

Comments: To appear in the Astrophysical Journal; 10 pages, no figures

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0712.3558v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Rosanne Di Stefano [view email]

[v1] Thu, 20 Dec 2007 20:01:17 GMT (25kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0712.3558

Discovery and Study of Nearby Habitable Planets with Mesolensing

Authors: Rosanne Di Stefano, Christopher Night

(Submitted on 9 Jan 2008)

Abstract: We demonstrate that gravitational lensing can be used to discover and study planets in the habitable zones of nearby dwarf stars. If appropriate software is developed, a new generation of monitoring programs will automatically conduct a census of nearby planets in the habitable zones of dwarf stars. In addition, individual nearby dwarf stars can produce lensing events at predictable times; careful monitoring of these events can discover any planets located in the zone of habitability.

Because lensing can discover planets (1) in face-on orbits, and (2) in orbit around the dimmest stars, lensing techniques will provide complementary information to that gleaned through Doppler and/or transit investigations. The ultimate result will be a comprehensive understanding of the variety of systems with conditions similar to those that gave rise to life on Earth.

Comments: 12 pages, 3 figures, 1 table

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0801.1510v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Christopher Night [view email]

[v1] Wed, 9 Jan 2008 21:06:22 GMT (111kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0801.1510

Discovery and Study of Nearby Planetary and Binary Systems Via Mesolensing

Authors: R. Di Stefano

(Submitted on 9 Jan 2008)

Abstract: This paper is devoted to exploring how we can discover and study nearby (less than 1-2 kpc) planetary and binary systems by observing their action as gravitational lenses. Lensing can extend the realm of nearby binaries and planets that can be systematically studied to include dark and dim binaries, and face-on systems. As with more traditional studies, which use light from the system, orbital parameters (including the total mass, mass ratio, and orbital separation) can be extracted from lensing data, Also in common with these traditional methods, individual systems can be targeted for study. We discuss the specific observing strategies needed in order to optimize the discovery and study of nearby planetary and binary systems by observing their actions as lenses.

Comments: 12 pages, 4 figures, submitted to ApJL 14 September 2007

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0801.1511v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Rosanne Di Stefano [view email]

[v1] Wed, 9 Jan 2008 21:19:47 GMT (234kb,D)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0801.1511

Astronomers using Hubble have compiled a large catalogue

of gravitational lenses in the distant universe, finding 67

galaxies lensed by massive elliptical and lenticular-shaped

galaxies. If this is representative, there might be nearly

500, 000 similar gravitational lenses in total over the whole

sky.

More at:

http://www.esa.int/esaSC/SEMVGMVHJCF_index_0.html

So, how long would it take, using best current technology to get a telescope out to 500 AU? 10 years? 100 years? 200 years?

Second question:

How much of the sky would any particular gravity lens telescope be able to examine? The light rays that would be focused by the sun and be able to be caught by the telescope have to come from only a small portion of the sky I would think, or am I missing something? Seems like you would need a whole sequence of gravity lens telescopes — if you have one positioned to catch the light rays being focused by the sun from, say, Alpha Centari, (or rather the portion of space Alpha Centari is located in) you would have to have another one positioned somewhere else around the 500 AU sphere to catch the light rays coming from, say, Vega. How big a portion of the sky could a ‘present day technology’ telescope examine with gravity lensing?