What were the first objects in the universe? They may have been enormous stars a thousand times more massive than the Sun. If so, new observations suggest the apparent clusters found by the Spitzer Space Telescope could be the first galaxies, tiny by Milky Way standards and containing the mass of less than a million Suns. By contrast, the Milky Way today seems to house at least a 100 billion stars, and may be the result of the merging of far smaller galaxies like these.

This is remarkable stuff. Spitzer is looking at patchy infrared light found across the entire sky, light that comes from vast objects more than 13 billion years away. That number catches the eye, of course, because the universe is now thought to be some 13.7 billion years old. The light, which is either from stars or violent black hole activity, was once ultraviolet or optical, but the expansion of spacetime has stretched it into the infrared.

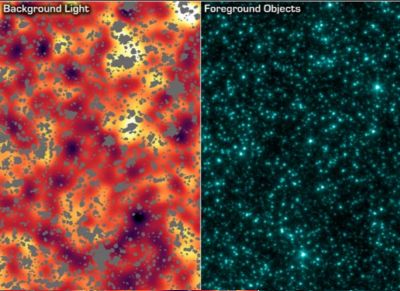

Image: The right panel is an image from NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope of stars and galaxies in the Ursa Major constellation. This infrared image covers a region of space so large that light would take up to 100 million years to travel across it. The left panel is the same image after stars, galaxies and other sources were masked out. The remaining background light is from a period of time when the universe was less than one billion years old, and most likely originated from the universe’s very first groups of objects — either huge stars or voracious black holes. Darker shades in the image on the left correspond to dimmer parts of the background glow, while yellow and white show the brightest light. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/GSFC.

Ancient light. Its fluctuations, visible when the light from foreground stars and galaxies is removed, reveal the clustering. Says Alexander Kashlinsky (NASA GSFC), “We are pushing our telescopes to the limit and are tantalizingly close to getting a clear picture of the very first collections of objects. Whatever these objects are, they are intrinsically incredibly bright and very different from anything in existence today.”

Kashlinsky is co-author on two reports slated to appear in the Astrophysical Journal Letters. A preprint of “New measurements of cosmic infrared background fluctuations from early epochs” is available here, and “On the nature of the sources of the cosmic infrared background” is also online at the arXiv site. Once again, Spitzer does yeoman work, but it may take the James Webb Space Telescope to definitively nail the identity of these clusters down.

Hi Paul

As usual the science press gives us the Light Travel Time NOT the actual distances that are worthwhile. “13 billion light years” is a lazy way of saying a red-shift of 8 or so. In actual fact in the consensus cosmos the distance is near 30 billion light years.

The co-moving radial distance is D = (c/H)*ln(1+z), where c/H is the Hubble distance (13.7 billion ly) and z is the red-shift observed for the source in question. The velocity of the object is related by (1+z)= exp(v/c), thus in this case the sources seen from 13 billion years ago are moving faster than light relative to us, not to themselves. They see us as we were 13 billion years ago receding at the same pace.

Relativity means we can all be the centre of the Universe ;-)

Adam

Hi, My Questions an thoughts- Is this as far back as the universe goes; or as far back as we can see clearly, (with current telescopes)? the image background light looks a bit blurred?

leaving this picture open to many interpretations, how far back can we look before the wavelengths of light, are stretched out into longer wavelengths (redshifted)so much they become flat, and can’t be seen? thanks kali