A continuing preoccupation at Centauri Dreams is long-term thinking. What can we as a species do to extend our time-frame beyond the infuriating short-term outlook of today, so that we can start thinking realistically about shaping a future beyond our own lifetimes? This kind of thinking will be necessary when we build our first interstellar probes, traveling journeys that will surely take decades and may involve centuries. What will drive us to think and plan within the millennial time frames that would allow humans to expand into and throughout the galaxy?

Novelist Stephen Baxter addresses this question in a recent paper in the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. Baxter points out the enormity of the time challenge: Voyager 1, the fastest human object ever built, travels at some 17.3 kilometers per second. It would reach Alpha Centauri (if headed in that direction) in 73,000 years. But starships that can reach 0.1c are not beyond possibility. If we can develop them, it’s possible to imagine a wave of colonization that slows to half that speed in the time needed to colonize and industrialize new worlds.

What you wind up with is human penetration of the entire galaxy in a time frame of perhaps a million years. In discussing these matters, Baxter draws on the work of Michael Hart (citation below). And he notes that a 100-year mission to Alpha Centauri seems within the reach of what he calls ‘conscious time.’ That is to say, we’ve already seen examples of programs that last several centuries, including the British Empire (growth and dissolution) and the establishment of the USA. Such projects are not fully defined by their originators, “…but they do show a continuity of vision, cultural values and purpose,” Baxter writes, “and they may originate in conscious decision-making.”

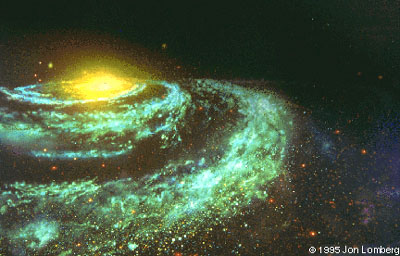

Image: The Milky Way as seen by an approaching traveler. Will humanity’s migration into the Galaxy be a matter of will, or a playing out of instinctive imperatives? Art copyright Jon Lomberg, www.jonlomberg.com. Lomberg’s superb work is well known; among other projects, he was chief artist for Carl Sagan’s series ‘Cosmos,’ and this image is part of the animation sequence that opened the series.

While not as sanguine as Baxter (I think a century-long project would require a drastic — and long overdue — reorientation of priorities in today’s society), I am cheered by the prospect that “…in the long term, it will only take a few refugees, for whatever motive, to flee from one crowded star system to the next to sustain an onward expansion.” The most significant settlers of North America tended to come, Baxter notes, for ideological, not economic, reasons, and a few refugees is all it takes to keep interstellar migration going.

Beyond ‘conscious time,’ in Baxter’s notion, is ‘dreaming time.’ Here we are talking of thousand year time frames, with expansion beyond the early outposts to a large number of nearby stars. A human institution that covers such a time frame: the Roman empire, which dominated the West for a thousand years. Baxter believes an idea of themselves that went beyond conscious planning enabled the Romans to create such a culture, and sees a continuity in such cultures that goes beyond intellect into the subconscious. And here is the crux:

What is important in this context is that ‘dream’-induced motivations appear to work themselves out at timescales longer than the ‘conscious’ – over millennia rather than centuries. And therefore what may unite us with our much-transformed starfaring descendants, over the epochs of the second Hart timescale, will not be abstractinos of the intellect but more mystical ties. Perhaps we will build starships as we build cathedrals, as repositories of faith sailing into the future.

Finally, Baxter discerns what he calls ‘genetic time,’ driven by the interests of biology and human genes. If the working out of genetic imperatives drives our species, it ultimately becomes inappropriate to talk of ‘purpose’ on the largest time scales. Our movement across the Galaxy may take place in the same way species move into ecological niches, driven by an expansion that the species seems unable to curb consciously. Such a movement ‘…may be carried aboard starships maintained with the unthinking accuracy with which a bower bird builds her nest — and for similar purposes.”

Note several key Baxter assumptions: first, that we will remain restricted by known physics; a warp drive, needless to say, changes everything. Second, that while we may find life on other worlds, it will probably not be intelligent. The discovery of sentient aliens along the route of expansion clearly creates a whole new set of possibilities!

Baxter’s paper is “A Human Galaxy: A Prehistory of the Future,” in JBIS Vol. 58, pp. 138-142. The Michael Hart paper he draws from is “An Explanation for the Absence of Extraterrestrials on Earth,” in Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society 16, pp. 128-135, a study that deserves (and will soon get) a review in these pages.

Hi Paul

This is an interesting paper (and post) which I’m rather annoyed that I missed. Any more you can tell me about it? I’m hoping to raid my Alma Mater’s library for my bi-annual dose of JBIS, so thanks for the pointer.

I will have to subscribe one of these days.

BTW I found this post courtesy of Google

Adam, I’ve got that paper somewhere around here in the chaos of my office. Let me dig it up and I’ll pass along more info.