Among the plans for NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) is a research agenda some of us have been hoping for for years. Designed to scan the entire sky in infrared light, the spacecraft should be able to locate nearby brown dwarfs. The possibility that one or more of these dim objects might actually be closer to us than Proxima Centauri cannot be ruled out, and if we were to find a brown dwarf one or two light years away, it would inevitably become the subject of mission speculation for next generation technologies.

Not that we know how to travel even one light year in a reasonable amount of time, but halving the distance to the nearest star would surely make such a mission more tenable. Note the progression: We’re already flying our first Kuiper Belt mission, if you take into account the plan for New Horizons to investigate icy objects beyond Pluto. We’re putting together mission concepts like Innovative Interstellar Explorer that could push well outside the heliosphere. Our studies of the Kuiper Belt lead eventually to the gravity focus and missions like Claudio Maccone’s FOCAL, designed to take advantage of the Sun’s lensing effects to study remote objects whose light is focused by gravity.

The Oort Cloud, which may extend as far out as a light year, is the domain of the long-period comets. And perhaps a brown dwarf? Assuming the primary Centauri A and B stars have a cometary cloud of their own, Proxima Centauri is well within it. Proxima is a larger, M-class red dwarf, but it reminds us that finding a dim object even in the local neighborhood would not be a surprise. Take into account possible brown dwarfs and you paint a picture of interstellar space that is far from empty. The exciting thing is that we don’t know much about brown dwarfs and can only speculate as to their numbers. Some researchers think they’re all over the sky:

“Brown dwarfs are lurking all around us,” said Dr. Peter Eisenhardt, project scientist for the mission at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif. “We believe there are more brown dwarfs than stars in the nearby universe, but we haven’t found many of them because they are too faint in visible light.”

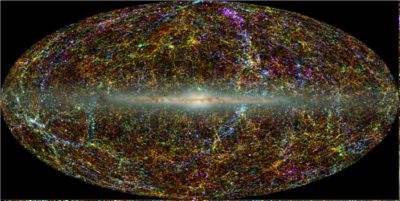

More brown dwarfs than stars… It’s quite a thought, and add to it that brown dwarfs seem to be able to support planetary systems of their own. The Spitzer Space Telescope has made those findings possible, and WISE will add significantly to our knowledge of the nearby infrared universe, not to mention what it might reveal about distant galaxies shrouded in dust. The image below, taken from the 2 Micron Sky Survey, gives a glimpse of what infrared imaging on a wide scale can accomplish. Be sure to click to enlarge this one for a breathtaking view.

Image: Panoramic view of the entire near-infrared sky reveals the distribution of galaxies beyond the Milky Way. The image is constructed from the more than 1.5 million galaxies in the 2MASS Extended Source Catalog (XSC), and the nearly 500 million Milky Way stars in the 2MASS Point Source Catalog (PSC). The galaxies are color-coded by their distances inferred from their photometric redshift (def.) deduced from the K band (2.2 microns) or as given in the NASA Extragalactic Database (NED). Blue are the nearest sources (redshift < 0.01); green are at moderate distances (0.01 < redshift < 0.04) and red are the most distant sources that 2MASS resolves (0.04 < redshift < 0.1). Credit: Two Micron Sky Survey (2MASS).

And for those of you who remember IRAS -- the Infrared Astronomical Satellite launched in 1983 -- WISE will be 500 times more sensitive. Launch is expected in 2009, but to follow WISE news in the interim, keep an eye on its news page.

Hi Paul

A nearby dwarf would be pretty amazing, though wouldn’t it be more obvious by now if it was there? The Binary Institute reckons the Sun has a BD companion in a 24,000 year orbit, but that’s incredibly close and would surely stick out like a sore thumb in all-sky infrared scans like that one.

As for crossing a lightyear, we know how to do it, but just don’t want to pay the cost – an Orion using thermonuclear pulse units would span that gap easily in just a few decades. But the cost would be hefty – fiscally and politically. Wonder what you motivate us enough to go all out to reach a BD?

The November “Analog” had a fact article by Greg Matloff which discussed developments related to near-term interstellar solar-sails. He advocates perforated dielectric sails with diamond strength lines which should reach about 1,000 km/s with a manned payload, and maybe 3,000 km/s with an unmanned probe. An elegant way to slowly get between the stars, with none of the complications of in-space energy beams able to fry a planet.

Adam

Adam, that 3,000 km/s catches the eye, doesn’t it? Matloff has investigated sail possibilities at great length so it’s always interesting to hear his latest thinking on the subject. And it drives home to me the fact that interstellar technologies are not that far away. Sure, finding a sudden breakthrough that gives us a warp drive or the like would be wonderful, but in the absence of such a drive, various sail strategies are still viable even though they take a lot longer. And yes, avoiding that planet-frying energy beam is a good idea!

While I like the feasibility of the solar sail, I would like it to do something more than the equivalent of seeing how far we can throw a rock. Pioneer is in a sense a slower rock (yes, I know we got lots of science out of it). Perhaps an exploration of the Kuiper belt to give an objective that people can more easily grasp, and also test robotics, communications and manouverability.

Going interstellar requires far more structural and electronic longevity than we have in hand, and intelligent robotics, unless we just like to hurl rocks. I would want the probe to arrive safely, do exploration, and return useful science, preferably by communications and not by round-trip return (faster results that way). That’s a lot to ask. We’ll get there in time.

Of course if we come up with a warp drive in the interim, our grandchildren can go out and pick up the enroute sail probe and put it in a museum.

Astrophysics, abstract

astro-ph/0701703

From: Alexander Scholz [view email]

Date (v1): Wed, 24 Jan 2007 20:46:12 GMT (104kb)

Date (revised v2): Wed, 24 Jan 2007 21:00:54 GMT (104kb)

Evolution of brown dwarf disks: A Spitzer survey in Upper Scorpius

Authors: Alexander Scholz (Toronto, St. Andrews), Ray Jayawardhana (Toronto), Kenneth Wood (St. Andrews), Gwendolyn Meeus (AIP), Beate Stelzer (Palermo), Christina Walker, Mark O’Sullivan (St. Andrews)

Comments: 39 pages, 7 figures, accepted for publication in ApJ

We have carried out a Spitzer survey for brown dwarf (BD) disks in the ~5 Myr old Upper Scorpius (UpSco) star forming region, using IRS spectroscopy from 8 to 12\mu m and MIPS photometry at 24\mu m. Our sample consists of 35 confirmed very low mass members of UpSco. Thirteen objects in this sample show clear excess flux at 24\mu m, explained by dust emission from a circum-sub-stellar disk. Objects without excess emission either have no disks at all or disks with inner opacity holes of at least ~5 AU radii. Our disk frequency of 37\pm 9% is higher than what has been derived previously for K0-M5 stars in the same region (on a 1.8 sigma confidence level), suggesting a mass-dependent disk lifetime in UpSco. The clear distinction between objects with and without disks as well as the lack of transition objects shows that disk dissipation inside 5 AU occurs rapidly, probably on timescales of

Astrophysics, abstract

astro-ph/0702034

From: Kelle Cruz [view email]

Date: Thu, 1 Feb 2007 19:23:16 GMT (77kb)

A New Population of Young Brown Dwarfs

Authors: Kelle L. Cruz, J. Davy Kirkpatrick, Adam J. Burgasser, Dagny Looper, Subhanjoy Mohanty, Lisa Prato, Jackie Faherty, Adam Solomon

Comments: 5 pages, contribution to proceedings for the 14th Cambridge Workshop on Cool Stars, Stellar Systems and the Sun, 6-10 November 2006

We report the discovery of a population of late-M and L field dwarfs with unusual optical and near-infrared spectral features that we attribute to low gravity — likely uncommonly young, low-mass brown dwarfs. Many of these new-found young objects have southerly declinations and distance estimates within 60 parsecs. Intriguingly, these are the same properties of recently discovered, nearby, intermediate-age (5-50 Myr), loose associations such as Tucana/Horologium, the TW Hydrae association, and the Beta Pictoris moving group. We describe our efforts to confirm cluster membership and to further investigate this possible new young population of brown dwarfs.

http://arxiv.org/abs/astro-ph/0702034

Astrophysics, abstract

astro-ph/0703106

From: Simon Goodwin [view email]

Date: Tue, 6 Mar 2007 09:16:34 GMT (13kb)

Brown dwarf formation by binary disruption

Authors: Simon P. Goodwin (Sheffield), Ant Whitworth (Cardiff)

Comments: 6 pages, no figures. Accepted for A&A

Context: The principal mechanism by which brown dwarfs form, and its relation to the formation of higher-mass (i.e. hydrogen-burning) stars, is poorly understood.

Aims: We advocate a new model for the formation of brown dwarfs.

Methods: In this model, brown dwarfs are initially binary companions, formed by gravitational fragmentation of the outer parts (R > 100 AU) of protostellar discs around low-mass hydrogen-burning stars. Most of these binaries are then gently disrupted by passing stars to create a largely single population of brown dwarfs and low-mass hydrogen-burning stars.

Results: This idea is consistent with the excess of binaries found in low-density pre-main sequence populations, like that in Taurus, where they should survive longer than in denser clusters.

Conclusions: If brown dwarfs form in this way, as companions to more massive stars, the difficulty of forming very low-mass prestellar cores is avoided. Since the disrupted binaries will tend to be those involving low-mass components and wide orbits, and since disruption will be due to the gentle tides of passing stars (rather than violent N-body interactions in small-N sub-clusters), the liberated brown dwarfs will have velocity dispersions and spatial distributions very similar to higher-mass stars, and they will be able to retain discs, and thereby to sustain accretion and outflows. Thus the problems associated with the ejection and turbulence mechanisms can be avoided. This model implies that most, possibly all, stars and brown dwarfs form in binary or multiple systems.

http://arxiv.org/abs/astro-ph/0703106