by Gregory Benford

Centauri Dreams is pleased to present the travels of Gregory Benford, just returned from a multi-week journey that took him to Sri Lanka to see Arthur C. Clarke, around the southern Indian coast all the way to Bombay, thence to Jaipur, Delhi and finally on to Singapore. The well-known physicist and science fiction author portrays lands awash in history but laden with potential for a possible future off-planet. Will a China/India space race revitalize manned spacecraft technologies? Enjoy the journey and be sure to check the Benford & Rose site for the author’s recent essays and commentaries.

We left February 17, 2007 on a considerable, month-long trip, starting with Hong Kong. We caught the Lunar Celebration at Chinese New Year—huge crowds, spectacular fireworks. Then on to Colombo, Sri Lanka, to visit Arthur C. Clarke.

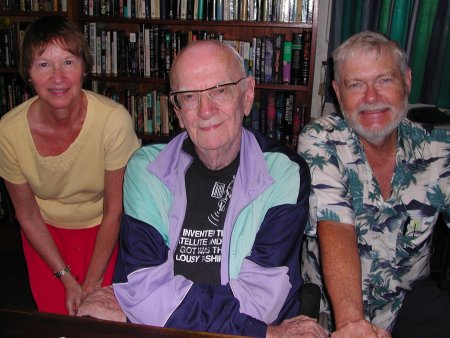

Arthur has post polio syndrome and thus very little memory or energy. He turns 90 this December and wants to keep in touch with the outer world, mostly through the Internet. He has few friends left in Colombo. He took us to the Colombo Swimming Club for lunch, a sunny ocean spot left over from the Raj. It felt somehow right to watch the Indian Ocean curl in, foaming on the rocks, to the tune of gin and tonics — and to speak of space, that last, greatest ocean. Science fiction is to technology as romance novels are to marriage: a sales pitch. But without vision and then persuasion, little would ever happen. Arthur has always known that.

Image: Elisabeth Malartre. Arthur C. Clarke and Gregory Benford.

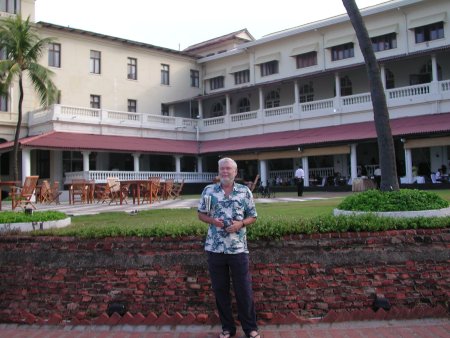

Our hotel with a similar ocean view. The Galle Face is the oldest grand Raj hotel east of Suez, dating from before the Civil War, and reeks of atmosphere. On the veranda we daily dug into a good Lankan breakfast: string hoppers of woven rice, rich curry of meat and potatoes, papadams – cause for lascivious hunger. Sri Lanka sits a few degrees from the equator an island long ago named Serendip, for its fortunate circumstances.

Not all is fortunate now, though. The civil war between the Sinhalese government and what even the Times of Delhi terms “the fascist Tamil Tigers” (18% of the population) has now run 23 years, killing hundreds of thousands. Since the Galle Face is next to the British High Command compound, and just down the street from the presidential residence, subtle security lurks everywhere. A heavy machine gun on a nearby tower peered over us as we swam in the pool. Arthur mused, “All this effort, all this death, when we could be building the staging area for a seaborne space elevator.” In The Fountains of Paradise he had moved the island five degrees south so it could sit on the equator.

Image: The author at the Galle Face Hotel in Colombo.

We flew to Madras to link up with a tour, Zegrahm Expeditions, which took us down south by air to see some fantastic Hindu temples. Then to the coast, where our ship, Le Levant, ushered us into elegant rooms and well coordinated programs. Great food, careful handling, generally superb. I had spent two previous month-long trips to India, roughing it around the north, largely on my own. Time to take it easy!

Around the southern point of India we went, sailing along the west coast state of Kerala. We stopped each day at a port town, went to see sites and experiences—farming, rubber plantation, fruit harvesting, plus the inevitable temples. Heat, humidity, rich smells. I watched some old Indian fishing, using throw nets, just as I once did on the Gulf Coast, and my relatives still do. But here they get little fish and crabs, with shrimp the best haul, and few per cast. The entire coast is fished out, and each year the fish markets display smaller fare.

One oddity was the poor women who walked neck-high through the muddy water, towing plastic jugs. They massage the bottom sludge with their feet, feeling the mud smelt that hide there. When one stirs under a foot, they can propel the thrashing, palm-sized smelt up with their feet, grab it in hand, and pop it into their jugs. With plastic bags over their hair to keep off sun and water, they earnestly work their way in teams along the bay. The smelt are smaller than their palms.

There I had a milk-white toddy that smelled of raw rubber, but it was juice already fermented in the shell, when a toddy-walla freshly drained it from a coconut. Fierce, sharp, warming the belly: nature’s cocktail.

I body surfed the warm waves of the Arabian Sea in Goa, which was much like the Gulf Coast of Alabama. We left the ship in Bombay and stayed for a couple of days. Southern India is disorganized and dusty, but there aren’t quite so many people, either. The north never lets you forget what it means to travel in a nation of 1.2 billion. Even in an over-airconditioned room in a giant hotel you hear mad beeping outside from the cars—the horn is a basic tool, used to announce overtaking someone. Our room faced the harbor and the Gate of India, an 18th century stone archway. The painted caves of Elephanta Island, just across the bay by ferry, were mysterious. The Portuguese blasted some of them with rifles since they were ancient religious images of Shiva, Krishna, etc., insults to Christ. But they didn’t dare attack temples very much. The Brits wisely left religion alone entirely.

We stayed in Taj chain hotels when not cruising, top of the line. Pools, wireless, fine food, plentiful staff. The pools don’t need heating and keep one fresh, though not all have a heavy machine gun brooding over them. Elsewhere this luxury would isolate you, but in India it’s a good idea. The wear and tear of travel, especially overland, is large. The “cobra roads” are rocky, traffic a nightmare (and opposite handed), while everything runs on IST— Indian Standard Time, which becomes Indian Stretchable Time. The moist heat penetrates to the bone. Crowds are huge, poverty lurks everywhere. Education is better in the south, though political power is in the north. While Indians laud their diversity, they really mean their many religions and castes; there were few blacks or orientals.

We flew to Jaipur and saw the 16th C. astronomical observatory, used to get accurate planetary orbit information, about the same time that Copernicus was figuring out elliptical orbits in Poland. Women wear very colorful saris that work well with their dark, smooth skin. Onward then, in grinding bus trips to Agra and the Taj—indescribably beautiful, so I won’t. It still seems odd, despite my two earlier, month-long trips to India (22 and 10 years ago, when roads were even worse), that the most beautiful building in the world is a tomb. Ethereal in its grace, hanging in the sky like a vision. Yet it’s about death, and the perpetual wish for eternal life. There’s even a cremation ghat nearby on the river.

Image: At the Taj Mahal.

Everywhere springs a colorful profusion of temples, religious icons and symbolism. I reflected anew that the opiate of India is indeed religion. It and China alone have religions with reincarnation, the cycle of time supposedly going back infinitely far. Buddhism came from India and caught on better in China. These two vast, ancient societies withstood the centuries by keeping down innovation, so life was much the same from one millennium to the next. Centuries slid by with little to mark them beyond the feuding of maharajahs. Maybe that’s key to why the wheel of life idea works so well there. Notably, one of the few diehards supporting the Steady State theory in cosmology is Wickramsingh, a Brahmin; maybe he feels a cultural resonance.

The air was thick with mortality. Tombs of emperors loom over traffic roundabouts, forgotten forts of red sandstone stand ready to defend shopping malls, street names reflect dynasties that lasted centuries. You see in passing turbaned Sikhs and sleek Bengalis, dark and beautiful Tamil women from the moist south, Rajputs ablaze with jewelry, raw Kashmiris smelling of untanned leather, uniformed soldiers clumping by, black-cloaked Muslim women, peasants hauling bullock-drawn freight from the scorched Punjab plains.

Beggar children know to murmur key words—”mummy,” “hungry,” “please,” “baby”—in soft despairing tones to snare the hurrying stranger. They and the hawkers throng the tour buses and sites, earning their keep with lifted palms, to live in the shantytowns of packing cases and rusty tin that line bustling avenues. Gandhi said the voice of the people was the voice of God, but it was hard to see a divine element in the grinding poverty, whatever it said.

At an ordinary town’s edge is the usual rubble—vacant-eyed children, vivid plastic bits, sagging shacks that shade listless adults, dogs bent or crippled, scrawny chickens pecking through litter, ugly sweet smells from stagnant ditches, brown fruit peelings awaiting a passing pig, cow patties drying on a wall. (A common energy source in homes.) Some women seemed at ease as they squatted to soap themselves and then their clothes in rain puddles. Misery hung in the air. One sees stories drifting by in a single glimpse: a sick dog eating withered grass, a twisted leg, an ancient brown woman squatting so that she could lift her matted sari away from the road, to relieve herself while she watched traffic with glittering eyes. Yet there was beauty, too. Pied wagtail birds flitting, their eager grace somehow heartening.

Image: Cow patties stacked for burning in homes.

India’s socialist beginnings served them poorly as population swelled. Delhi started in their 1947 independence with 250,000; now it has 14 million, thanks to the huge bureaucracy. Their constitution wrote in preferences for the lower castes, rules which were slated to go away in a generation, but now seem permanent; indeed, political pressure expanded them steadily, adding “tribes” (ethnicities)—and many political parties based on these favors wants to do more. A useful lesson on affirmative action.

The many newspapers in English have a curiously vague tone. They say “communal disturbances” for the incessant Muslim-Hindu strife. Most news comes in passive voice—as Orwell observed a half century ago, to evade responsibility. Criticism of the US is common. One whole page advocated taking the Internet’s basic controls away from the US, which makes access free to all, and handing it to the UN or some other body. The subtext seems to be to first internationalize, then tax it.

Delhi is a powerhouse. Our hotel faced the large forest embedded by the Brits in the new southern half of town, with its broad, large buildings of state. The trip had run 25 days and we were ready to go home, with a stop in Singapore for business. The Victorian houses have arched doorways twelve feet high, as if awaiting a family of acrobats who would need to walk between rooms while still stacked on each others’ shoulders. Indeed, India’s survival is acrobatic at times. They have come through the hard decades of socialist poverty and, since the early 1990s, are finally emerging, using market forces to get jobs and decent conditions throughout the land. There is still an ocean of poverty, and nothing will work if family size doesn’t drop; about half of the country is under 25.

India views technological problems quite differently. They import 60% of their energy needs and 90% of its oil. The Energy Minister announced while we were there that India will quadruple its coal burning by 2030, shrugging off the entire idea of carbon restriction as a method to restrain climate change—even though, in the tropics, they have the most at risk. I try to explain this to climate scientists who hold with the prohibition-only stance, but they cannot grasp how differently the developing nations see the problem—basically, thinking it’s up to the prosperous nations. Similarly, the Indian space program sees itself as a rival to China, not to the US or Europe. It will be amusing if audacious moves in space come from Asia as a regional competition, just as the US-USSR contest drove the first decades.

In Delhi one easily gets the point of Kenneth Galbraith’s remark, that India is ‘a functioning anarchy’. Mahasweta Devi’s more literary take is that India walks “hand in hand with the new millennium, whistling a tune from the dawn of time.” Yet they have nuclear weapons in the nation of Gandhi.

Over 300 million Indians read English, with comparable numbers in China. These numbers resemble the entire US audience, suggesting that science and science fiction alike have a vast, ready audience in the heart of Asia. The natural medium to reach them with a rationalist, future-directed literature is the Internet. It’s all that keeps us in touch with Arthur Clarke, now. This possibility, I sensed, is the real frontier between cultures. The door yawns open.

The dusty Delhi airport is like a Mexican one of 30 years ago. Crowds mass at the entrances to canyons of barren, bare concrete, without even any shops. Security crew are sleepy-eyed, indolent, going through the motions. Goodbye to the vast subcontinent.

In comparison, our few days in Singapore were dramatic—clean, prosperous, orderly. Another Brit colony, rich in history. For $22 US I had a Singapore Sling in the Long Bar of the Raffles Hotel — mahogany, teak, broad fans flapping from the ceiling –which boasts a museum about its own history. The botanical gardens were our high point—lush tropical zones, a wonderful orchid garden, exotic birds.

I looked into moving to Singapore an intellectual property biotech company I co-own, because it’s far easier to defend property there than in lawyer-plagued USA. The Singapore government even gives grants to get high tech startups into the country. I had explored this in India, only to learn that, realistically, it would take a year of bureaucratic delay, to be dodged only by generous baksheesh. Sobering.

Singapore is known for its tough-minded policies, though they’ve repealed the strict laws against littering, spitting etc. Certainly it’s nothing like freewheeling Hong Kong, where sari-clad, Indian prostitutes accosted me outside our hotel, offering services that fell in price within seconds as I brushed them off. In a supposedly communist country!

After 28 days, we headed home. This glance into four very different former British colonies had revealed much, seen from the American angle. Everywhere the press of crowds reminds that the US is a rather under-populated land – and the price of letting that change. Passing through a village, thousands of faces stare back—people just sitting, with nothing much to do.

Of them, Singapore and Hong Kong are far more polished and prosperous, perhaps because they blend Chinese and other cultures well. Sri Lanka is a beautiful land, but India promises the most for the future. Dusty, disorderly, corrupt, yes—but vast and powerful, when it can decide what to do. These nations are the newest addition to what I call the Anglo Saxon Empire—one of culture, not class or race—and could become the true leader of all Asia. I hope they do.

I would like to do the same trip… :)

Wow! More English speakers in India than in the “motherland”… there’s an irony. Perhaps in a millennium (or less) it will be known as “Inglish” and its original home a minor footnote in history. About 24 years ago my family went to Japan and we had the strange experience of eating in an Indian restaurant in Tokyo run by Indians from Melbourne, Australia. Says something about the great Indian Diaspora.

An equal irony is that a Japanese punk band, Mack Pelican, now calls Melbourne home. It’s a small world.

Adam

On the subject of irony, best Indian cuisine I’ve ever had was to be found in Glasgow. Thanks for posting this wonderful essay. I’m looking forward to doing some travel around Asia this year, so it whets my appetite!

Chris, I’m not surprised re Glasgow. Some of the best Indian food I’ve ever had was in Inverness!

This is a marvelous piece, at once attracting and also repelling me from Southeast Asian travel — I like seeing the area through the eyes of intelligent observers. And I believe that Indians, especially Indians, speak the best English, language that’s rich and imaginative. The British ‘presence’ gave them this linguistic opportunity, a presence so helpful to India in spite of oppressiveness.

Hi Greg;

Nice trip. Glad you got to see Arthur (he’s lost weight, which is hardly surprising). Did you see the bronze bust of him inside the Galle Face? He doesn’t think it looks like him…I disagree.

Your nocturnal encounter in Hong Kong brings back memories. Remember the old line, “No sex please, we’re British”. I wonder…if you’re a British Communist, does that mean you’d have negative sex, and how does that work?

Take care…see you around.

Alan

nice to hear about your trip gregory,felt bad however upon reading of the poverty and arthur c clarkes illness.i know all his fans and admirers certainly wish him the best! i forsee (obviously among others),that india will indeed be a major space power. respectfully your friend george

hey futur : i tend to agree! :) george

Wonderful essay. Thank you, Greg!

“… best Indian cuisine I’ve ever had was to be found in Glasgow.” Best Indian cuisine I’ve ever had was to be found in Edinburgh. Second best Indian cuisine I’ve ever had was to be found in Victoria, BC.

Hurry up and award Sir Arthur C. Clarke the Nobel Peace Prize — he’s been on the short-list for it long enough.

It is only the Euroamerican perspective that diminishes the China-India space race. Odds are, that is the race which matters. Both are capable and serious. Japan, until they admit to a $2 x 10^12 debt overhang are out of the race. Europe, demographically challenged and starting to hit the wall with a Welfare State, is out of the race. The USA? Well, I used to differ with Jerry Pournelle about NASA. Now I agree with his suggested draconian remedy. Except that I wouldn’t allow our communist bureaucrats to wear a blindfold, or smoke a last cigaret.

Not flying the Sam Ting + 500 international collaborator’s antimatter detector on the ISS after spending ~ $1 x 10^9 is the last straw.

If it detected a single, say, anti-iron nucleus, that would strongly imply an antistar making anti-iron by antinucleosynthesis and dispersing it when it went antisupernova. But NASA in its infinute wisdom has decided not to fly the experiment, on the basis that all remaining Shuttle flights are needed to finish building the ISS, which won’t do any science. Or something.

I’d long ago proposed neutrino detectors on the Moon, to give a longer baseline for neutrino oscillation experiments.

http://www.magicdragon.com/ComputerFutures/SpacePublications/Sensors.html

and

“Mercury polar ice could provide neutrino detection opportunities…”

http://www.magicdragon.com/ComputerFutures/SpacePublications/Mercury_Ice.html

But I’m not looking for any grants. They money has all gone to Halliburton.

The best Indian food is from south India..check for Kerala Restaurants in London.