The early news from COROT couldn’t be more encouraging. Just sixty days into its science mission, the spacecraft has found its first transiting exoplanet and has returned information about the interior of a star. The latter findings point to COROT’s role in asteroseismology, the study of stellar interiors through analysis of the star’s light curves. What has mission scientists smiling is that in both cases, the instruments they’re watching show signs of working even better than planned.

True, the data carrying these results are still noisy and in need of plenty of analysis, but COROT project scientist Malcolm Fridlund sounds quite an optimistic note:

“The data we are presenting today is still raw but exceptional. It shows that the on-board systems are working better than expected in some cases – up to ten times the expectation before launch. This will have an enormous impact on the results of the mission.”

One would think so. It raises the stakes for COROT from detecting ‘super-Earths’ to finding an Earth-sized planet in transit. For now, though, we can be content with COROT-Exo-1b, a hot gas giant with radius 1.78 times that of Jupiter. Its primary is a yellow dwarf not dissimilar from the Sun in the direction of the constellation Monoceros, some 1500 light years away. Followup spectroscopic studies from the ground have determined a mass of 1.3 times Jupiter’s. The planet’s orbital period is about 1.5 days.

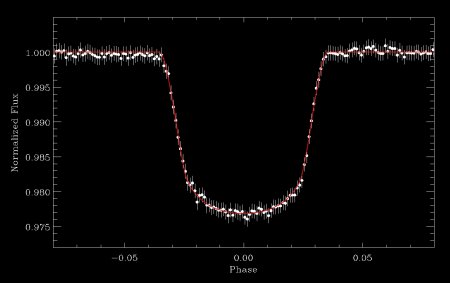

Image: This image shows the signature of the presence of a planet orbiting a star. The intensity of light coming from the star is represented on the y-axis whereas the x-axis shows the phase, or the revolution of the planet around the star. The amount of light from the star reaching COROT decreases each time the planet passes in front of the star itself. This is when the drop is registered. This was the first planet detected by COROT since the beginning of its mission. This light curve is part of a data set obtained between February and April 2007. Credit: COROT exo-team.

As to asteroseismology, COROT’s 50-day study of a Sun-like star (not the one that is home to the new exoplanet) showed luminosity variations on short time scales (a few days), perhaps related to the star’s magnetic activity. It will be fascinating to watch the science of ‘starquakes’ and other stellar events mature. COROT’s findings will provide data that should be useful in the challenging task we discussed the other day, determining the age of a given star.

This morning I asked Dr. Fridlund (via e-mail) how COROT separated its exoplanetary work from its asteroseismology, or whether the two were engaged in simultaneously on the same star. His response:

COROT has two cameras in the focal plane. One for asteroseismology and one for exo-planetology. They have different characteristics, since the stars you study for asteroseismological variations are brighter. In the former you have maybe a few hundred targets of different types (of which the published one is one of the brightest of the ones resembling our Sun). In the exoplanet field, on the other hand you have thousands of targets. In this first field about 6,000, and in the one planned with the most objects (the next one starting on 16 May and running until 16 October) there are no less than 12,000.

Let’s hope the good news continues (and congratulations to the COROT team for an outstanding mission thus far). While we await the upcoming Kepler mission and listen to the continuing debate over what technologies a Terrestrial Planet Finder should deploy to get actual images of distant worlds, COROT is already hard at work, the first space mission flown with the explicit purpose of detecting extrasolar planets. A French project developed with the help of the European Space Agency, COROT keeps Europe’s planet-hunting initiatives in the spotlight.

According to this article (and a similar one on New Scientist) :

http://www.spaceref.com/news/viewpr.html?pid=22570

COROT data is much better than expected and it will allow detection

of earth size planets. They were expecting to detect super-earths only.

We might get data on earth size planets well before Kepler.

Enzo

The CoRoT primary target HD 52265: models and seismic tests

Authors: M. Soriano, S. Vauclair, C. Vauclair, M. Laymand

(Submitted on 17 May 2007)

Abstract: HD 52265 is the only known exoplanet-host star selected as a main target for the seismology programme of the CoRoT satellite. As such, it will be observed continuously during five months, which is of particular interest in the framework of planetary systems studies. This star was misclassified as a giant in the Bright Star Catalog, while it is more probably on the main-sequence or at the beginning of the subgiant branch. We performed an extensive analysis of this star, showing how asteroseismology may lead to a precise determination of its external parameters and internal structure. We first reviewed the observational constraints on the metallicity, the gravity and the effective temperature derived from the spectroscopic observations of HD 52265. We also derived its luminosity using the Hipparcos parallax. We computed the evolutionary tracks for models of various metallicities which cross the relevant observational error boxes in the gravity-effective temperature plane. We selected eight different stellar models which satisfy the observational constraints, computed their p-modes frequencies and analysed specific seismic tests. The possible models for HD 52265, which satisfy the constraints derived from the spectroscopic observations, are different in both their external and internal parameters. They lie either on the main sequence or at the beginning of the subgiant branch. The differences in the models lead to quite different properties of their oscillation frequencies. We give evidences of an interesting specific behaviour of these frequencies in case of helium-rich cores: the “small separations” may become negative and give constraints on the size of the core. We expect that the observations of this star by the CoRoT satellite will allow choosing between these possible models.

Comments:

11 pages, 7 figures, to be published in Astronomy and Astrophysics

Subjects:

Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as:

arXiv:0705.2505v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Sylvie Vauclair [view email]

[v1] Thu, 17 May 2007 09:35:46 GMT (113kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0705.2505