Impressive results released today show just how much we’re learning about the ‘hot Jupiters’ that comprise about a quarter of known exoplanets. The first concern HD 149026b, a distant world which the infrared Spitzer instrument has shown to be the hottest planet ever studied. It’s somewhat smaller than Saturn but more massive, and is thought to contain more heavy elements than could be found in our entire Solar System outside the Sun itself, with a core as much as 90 times the mass of the Earth.

And the odd thing about HD 149026b is that for it to reach the measured temperature — a smoking 3,700 degrees Fahrenheit, or 2,300 degrees Kelvin — it would have to be absorbing just about all the starlight reaching it. The upshot is a planet whose surface is blacker than charcoal, re-radiating incoming energy in the infrared. What a view for the nearby traveler: “The high heat would make the planet glow slightly, so it would look like an ember in space, absorbing all incoming light but glowing a dull red,” said Joseph Harrington (University of Central Florida).

You study things like this by measuring the drop in infrared light that occurs when the transiting planet moves behind its star. This is an unusual planet indeed — Drake Deming (NASA GSFC), a co-author of the paper on this work, says it’s “…off the temperature scale that we expect for planets.” HD 149026b is 279 light years away in the direction of the constellation Hercules, and it is the smallest and densest known transiting exoplanet. Its conditions sunside make the second exoplanet we have to discuss seem almost pleasant by comparison.

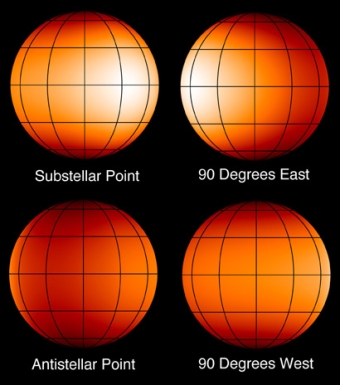

For HD 189733b, some 60 light years away and the closest known transiting exoplanet, shows temperatures (via Spitzer again) of 1,200 Fahrenheit on the day side (922 K) and 1,700 F at night (1,200 K), a relatively even range. We can thus deduce something more about its weather: powerful winds must be spreading the heat from dayside to nightside (assuming that this world is tidally locked to its star). These winds may be moving at more than 9,600 kilometers per hour, and the Spitzer studies show a warm spot — about twice the size of Jupiter’s Great Red Spot — 30 degrees east of the point directly below the star. From this, scientists extrapolate easterly moving winds that redistribute the intense heat.

Image: Four views of HD 189733b’s cloudtops in infrared light, each centered at a point of longitude 90 degrees from the last. A grid of longitude lines is superimposed on the map. These views clearly show a hot spot that is offset from the substellar point (high noon) by about 30 degrees. The offset may indicate fast “jet stream” winds of up to 6,000 mph (9650 km/h). Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Heather Knutson (CfA)

HD 189733b is a huge planet in an extremely close orbit, circling its star every 2.2 days. With more than a quarter million data points to play with, the team was able to assemble a simple map of this distant world. “We can see the changes in brightness as features in the planet’s atmosphere rotate into and out of view,” said Heather Knutson, a graduate student at Harvard and lead author of the paper on this work.

Will the James Webb Space Telescope permit even more finely detailed work, perhaps mapping weather patterns on planets as small as Earth? It’s certainly a possibility, and one to be mindful of as we look forward to getting the Webb instrument into space around 2013. The paper on HD 189733b is Knutson et al., “A map of the day-night contrast of the extrasolar planet HD 189733b,” Nature 447, (10 May 2007), pp. 183-186 (abstract here). The HD 149026b paper is Harrington et al., “The Hottest Planet,” Nature online publication 9 May 2007.

A map of the day-night contrast of the extrasolar planet HD 189733b

Authors: Heather A. Knutson, David Charbonneau, Lori E. Allen, Jonathan J. Fortney, Eric Agol, Nicolas B. Cowan, Adam P. Showman, Curtis S. Cooper, S. Thomas Megeath

(Submitted on 7 May 2007)

Abstract: “Hot Jupiter” extrasolar planets are expected to be tidally locked because they are close (

Hot Nights on Extrasolar Planets: Mid-IR Phase Variations of Hot Jupiters

Authors: N. B. Cowan, E. Agol, D. Charbonneau

(Submitted on 8 May 2007)

Abstract: We present results from Spitzer Space Telescope observations of the mid-infrared phase variations of three short-period extrasolar planetary systems: HD 209458, HD 179949 and 51 Peg. We gathered IRAC images in multiple wavebands at eight phases of each planet’s orbit. We find the uncertainty in relative photometry from one epoch to the next to be significantly larger than the photon counting error at 3.6 micron and 4.5 micron. We are able to place 2-sigma upper limits of only 2% on the phase variations at these wavelengths. At 8 micron the epoch-to-epoch systematic uncertainty is comparable to the photon counting noise and we detect a phase function for HD 179949 which is in phase with the planet’s orbit and with a relative peak-to-trough amplitude of 0.00141(33). Assuming that HD 179949b has a radius R_J

By all means … exo-planet studies are very interesting. But it is an extremly speculative business. This site is nowadays, according to me, focusing way to much on exo-planet studies. It´s confusing. No one really know anything about this planets except for the mass and orbit. The rest could only be speculations.

Per: clearly that is not all that is known, since this “weather map” is based on actual measurements of the temperature of the planet. This is not some speculative model we’re talking about here.

I really love reading about plenetary science, such that I really enjoyed this article very much. If there are recommended websites for planetary science neophytes, it would be wonderful to see them ranked on various levels and published for access by people such as myself. Let this be my profound thanks to all those who make these readings accessible.

Extent of pollution in planet-bearing stars

Authors: S.-L. Li, D.N.C. Lin, X.-W. Liu

(Submitted on 17 Feb 2008)

Abstract: (abridged) Search for planets around main-sequence (MS) stars more massive than the Sun is hindered by their hot and rapidly spinning atmospheres. This obstacle has been sidestepped by radial-velocity surveys of those stars on their post-MS evolutionary track (G sub-giant and giant stars). Preliminary observational findings suggest a deficiency of short-period hot Jupiters around the observed post MS stars, although the total fraction of them with known planets appears to increase with their mass. Here we consider the possibility that some very close- in gas giants or a population of rocky planets may have either undergone orbital decay or been engulfed by the expanding envelope of their intermediate-mass host stars. If such events occur during or shortly after those stars’ main sequence evolution when their convection zone remains relatively shallow, their surface metallicity can be significantly enhanced by the consumption of one or more gas giants.

We show that stars with enriched veneer and lower-metallicity interior follow slightly modified evolution tracks as those with the same high surface and interior metallicity. As an example, we consider HD149026, a marginal post MS 1.3 Msun star. We suggest that its observed high (nearly twice solar) metallicity may be confined to the surface layer as a consequence of pollution by the accretion of either a planet similar to its known 2.7-day-period Saturn-mass planet, which has a 70 Mearth compact core, or a population of smaller mass planets with a comparable total amount of heavy elements. It is shown that an enhancement in surface metallicity leads to a reduction in effective temperature, in increase in radius and a net decrease in luminosity. The effects of such an enhancement are not negligible in the determinations of the planet’s radius based on the transit light curves.

Comments: 25 pages, 8 figures, submitted to ApJ

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0802.2359v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Shulin Li [view email]

[v1] Sun, 17 Feb 2008 04:15:25 GMT (273kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0802.2359

Inverting Phase Functions to Map Exoplanets

Authors: Nicolas B. Cowan, Eric Agol (University of Washington)

(Submitted on 25 Mar 2008)

Abstract: We describe how to generate a longitudinal brightness map for a tidally locked exoplanet from its phase function light curve. We operate under a number of simplifying assumptions, neglecting limb darkening/brightening, star spots, detector ramps, as well as time-variability over a single planetary rotation. We develop the transformation from a planetary brightness map to a phase function light curve and simplify the expression for the case of an edge-on system.

We introduce two models–composed of longitudinal slices of uniform brightness, and sinusoidally varying maps, respectively–which greatly simplify the transformation from map to light curve. We discuss numerical approaches to extracting a longitudinal map from a phase function light curve, explaining how to estimate the uncertainty in a computed map and how to choose an appropriate number of fit parameters.

We demonstrate these techniques on a simulated map and discuss the uses and limitations of longitudinal maps. The sinusoidal model provides a better fit to the planet’s underlying brightness map, although the slice model is more appropriate for light curves which only span a fraction of the planet’s orbit. Regardless of which model is used, we find that there is a maximum of ~5 free parameters which can be meaningfully fit based on a full phase function light curve, due to the insensitivity of the latter to certain modes of the map.

Comments: 5 pages, 3 figures, accepted for publication in ApJL

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0803.3622v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Nicolas Cowan [view email]

[v1] Tue, 25 Mar 2008 20:01:30 GMT (250kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0803.3622

A Precise Estimate of the Radius of the Exoplanet HD 149026b from Spitzer Photometry

Authors: Philip Nutzman, David Charbonneau, Joshua N. Winn, Heather A. Knutson, Jonathan J. Fortney, Matthew J. Holman, Eric Agol

(Submitted on 6 May 2008)

Abstract: We present Spitzer 8 micron transit observations of the extrasolar planet HD 149026b. At this wavelength, transit light curves are weakly affected by stellar limb-darkening, allowing for a simpler and more accurate determination of planetary parameters.

We measure a planet-star radius ratio of Rp/Rs = 0.05158 +/- 0.00077, and in combination with ground-based data and independent constraints on the stellar mass and radius, we derive an orbital inclination of i = 85.4 +0.9/-0.8 degrees and a planet radius of Rp = 0.755 +/- 0.040 R_jup.

These measurements further support models in which the planet is greatly enriched in heavy elements.

Comments: 18 pages, 4 figures, submitted to ApJ

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0805.0777v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Philip Nutzman [view email]

[v1] Tue, 6 May 2008 18:52:58 GMT (119kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0805.0777

HD 179949b: A Close Orbiting Extrasolar Giant Planet with a stratosphere?

Authors: J.R. Barnes, Travis S. Barman, H.R.A. Jones, C.J. Leigh, A. Collier Cameron, R.J. Barber, D.J. Pinfield

(Submitted on 2 Jun 2008)

Abstract: We have carried out a search for the 2.14 micron spectroscopic signature of the close orbiting extrasolar giant planet, HD 179949b. High cadence time series spectra were obtained with the CRIRES spectrograph at VLT1 on two closely separated nights. Deconvolution yielded spectroscopic profiles with mean S/N ratios of several thousand, enabling the near infrared contrast ratios predicted for the HD 179949 system to be achieved.

Recent models have predicted that the hottest planets may exhibit spectral signatures in emission due to the presence of TiO and VO which may be responsible for a temperature inversion high in the atmosphere. We have used our phase dependent orbital model and tomographic techniques to search for the planetary signature under the assumption of an absorption line dominated atmospheric spectrum, where T and V are depleted from the atmospheric model, and an emission line dominated spectrum, where TiO and VO are present.

We do not detect a planet in either case, but the 2.120 – 2.174 micron wavelength region covered by our observations enables the deepest near infrared limits yet to be placed on the planet/star contrast ratio of any close orbiting extrasolar giant planet system. We are able to rule out the presence of an atmosphere dominated by absorption opacities in the case of HD 179949b at a contrast ratio of F_p/F_* ~ 1/3350, with 99 per cent confidence.

Comments: 9 pages

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0806.0298v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: John Barnes [view email]

[v1] Mon, 2 Jun 2008 14:50:34 GMT (224kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0806.0298

Exoplanet Mapping Revealed

Authors: Nicolas B. Cowan, Eric Agol (University of Washington)

(Submitted on 27 Jun 2008)

Abstract: One of the most exciting results of the Spitzer era has been the ability to construct longitudinal brightness maps from the infrared phase variations of hot Jupiters. We presented the first such map in Knutson et al. (2007), described the mapping theory and some important consequences in Cowan & Agol (2008) and presented the first multi waveband map in Knutson et al. (2008).

In these proceedings, we begin by putting these maps in historical context, then briefly describe the mapping formalism. We then summarize the differences between the complementary N-Slice and Sinusoidal models and end with some of the more important and surprising lessons to be learned from a careful analytic study of the mapping problem.

Comments: 4 pages, 6 figures, to appear in the Proceedings of IAU Symposium No. 253, 2008: Transiting Planets

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0806.4606v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Nicolas Cowan [view email]

[v1] Fri, 27 Jun 2008 20:00:22 GMT (46kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0806.4606

The 8 Micron Phase Variation of the Hot Saturn HD 149026b

Authors: Heather A. Knutson, David Charbonneau, Nicolas B. Cowan, Jonathan J. Fortney, Adam P. Showman, Eric Agol, Gregory W. Henry

(Submitted on 13 Aug 2009)

Abstract: We monitor the star HD 149026 and its Saturn-mass planet at 8.0 micron over slightly more than half an orbit using the Infrared Array Camera (IRAC) on the Spitzer Space Telescope.

We find an increase of 0.0227% +/- 0.0066% (3.4 sigma significance) in the combined planet-star flux during this interval. The minimum flux from the planet is 45% +/- 19% of the maximum planet flux, corresponding to a difference in brightness temperature of 480 +/- 140 K between the two hemispheres.

We derive a new secondary eclipse depth of 0.0411% +/- 0.0076% in this band, corresponding to a dayside brightness temperature of 1440 +/- 150 K. Our new secondary eclipse depth is half that of a previous measurement (3.0 sigma difference) in this same bandpass by Harrington et al. (2007). We re-fit the Harrington et al. (2007) data and obtain a comparably good fit with a smaller eclipse depth that is consistent with our new value.

In contrast to earlier claims, our new eclipse depth suggests that this planet’s dayside emission spectrum is relatively cool, with an 8 micron brightness temperature that is less than the maximum planet-wide equilibrium temperature. We measure the interval between the transit and secondary eclipse and find that that the secondary eclipse occurs 20.9 +7.2 / -6.5 minutes earlier (2.9 sigma) than predicted for a circular orbit, a marginally significant result. This corresponds to e*cos(omega) = -0.0079 +0.0027 / -0.0025 where e is the planet’s orbital eccentricity and omega is the argument of pericenter.

Comments: 17 pages, 12 figure, accepted for publication in ApJ

Subjects: Earth and Planetary Astrophysics (astro-ph.EP)

Cite as: arXiv:0908.1977v1 [astro-ph.EP]

Submission history

From: Heather Knutson [view email]

[v1] Thu, 13 Aug 2009 20:08:48 GMT (191kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0908.1977