Does anybody remember an old science fiction movie involving an attempt to snatch meteors from space? We’re talking something made probably in the 1950’s, and all I remember is a group of one-man spaceships sent up — for reasons that escape me — to go after meteors. You can imagine the dynamics of trying to catch a meteor with a scoop on a spacecraft. All subsequent attempts to identify this film have failed, but I was reminded of it by the discovery of a new mineral in a sample of interplanetary dust. Collecting the dust wasn’t quite as terrifying as the meteor-grabbing depicted in the movie, and the motivation for it was surely sounder.

In any case, it’s clear that you don’t have to go into deep space to collect interesting things. It was Scott Messenger (Johnson Space Center) who suggested that interstellar dust particles (IDPs) from a particular comet could be captured in the stratosphere if scientists chose their time carefully. Messenger zeroed in on comet 26P/Grigg-Skjellerup as a source for the IDPs in question, and follow-up dust collections by NASA involved high altitude aircraft flown out of Edwards Air Force Base in 2003.

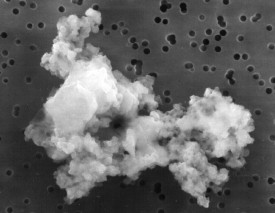

Image: Although not part of the sample gathered from comet 26P/Grigg-Skjellerup, this is a piece of interplanetary dust caught by a high-flying U2-type aircraft. It likely originates in the early days of our Solar System, being stored and later ejected by a passing comet. The particle is composed of glass, carbon, and a conglomeration of silicate mineral grains. It measures only 10 microns across, a tenth the width of a typical human hair. Credit: NASA.

Not only was the attempt successful, but 26P/Grigg-Skjellerup should turn out to be useful in future work, appearing as it does every five years. Team leader Keiko Nakamura-Messenger notes that grains of the newly identified mineral were a mere 1/10,000th of an inch in size. Fortunately, Johnson Space Center has a new electron microscope, and co-discoverer Lindsay Keller (JSC), like Nakamura-Messenger, was taken somewhat by surprise at what the instrument was able to find:

“Because of their exceedingly tiny size, we had to use state-of-the-art nano-analysis techniques in the microscope to measure the chemical composition and crystal structure of Keiko’s new mineral. This is a highly unusual material that has not been predicted either to be a cometary component or to have formed by condensation in the solar nebula.”

The new mineral is a manganese silicide now named Brownleeite, after Donald Brownlee (University of Washington, Seattle), a founder of interstellar dust particle research, and principal investigator of NASA’s Stardust mission. Turns out the trick isn’t to collect interplanetary dust — remarkably, the Earth collects about 40,000 tons of particles from space every year — but to pin down the sources of the particles. Most are assumed to come from disintegrating comets and asteroid collisions, and all are of interest because they offer information about the building blocks from which the Solar System was formed. The new mineral joins the other 4,324 minerals identified by the International Mineralogical Association, while reinforcing the case for interplanetary dust collection close to home.

The movie’s name is “rider’s to the Stars” from 1954:

http://us.imdb.com/title/tt0046240/

Frank

That’s it! Thanks, Frank. I knew I could count on finding an old movie buff who would recall this…

Hi Paul;

I hope this question does not sound to goofy.

When you say that the new type of mineral has been discovered as the interplanetary dust speck, do you mean a completely new mineral never before known to modern mineralogy, or just a new species discovered in space?

Either way, I am starting to become fascinated by interplanetary mineralogy so to speak, after reading the above article partly because we will most probably utilize off Earth resources in the future as we colonize our solar system and then reach out to the stars.

I wonder if we will ever find gem stone minerals in the Martian soil or crust. If enough of such were easily obtainable by Mars based mining efforts, I could imagine a huge market for Mars gemstones. They could truly be “like a diamond in the sky”. Pun intended.

Thanks;

Jim

Jim, the new mineral is a a combination of manganese and silicon that can be synthesized but has never been found occurring naturally on Earth. The International Mineralogical Association thus declares it a new mineral, adding to a list of over 4300 accepted minerals.

Hi Paul;

Thanks for answering my question.

I look foward to seeing what sort of mineral deposits we see on the moon as we go back and hopefully establish a permanent outpost, the same hopefully not to late for Mars, and then on from there. It should prove interesting.

Thanks;

Jim

If you’re anywhere near Santa Monica, Vidiots has a VHS copy for rental:

http://www.vidiotsvideo.com/results2.lasso?-database=vid6.fmp&-layout=DetailView&-response=detail.html&-recordID=12602761&-search

I just realized that William Lundigan is in it as well – he was the lead in the very realistic (for the 1950s) “Men into Space”

Frank

Yes, I saw via IMDB that William Lundigan was involved, and I do remember “Men into Space” very well. A terrific series for its time. I also noticed that Herbert Marshall, a great personal favorite, had a role here. Have to see this one again!

Clouds, Clumps, Cores & Comets – a Cosmic Chemical Connection?

Authors: S. B. Charnley, S. D. Rodgers (NASA Ames)

(Submitted on 18 Jun 2008)

Abstract: We discuss the connection between the chemistry of dense interstellar clouds and those characteristics of cometary matter that could be remnants of it. The chemical evolution observed to occur in molecular clouds is summarized and a model for dense core collapse that can plausibly account for the isotopic fractionation of hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen and carbon measured in primitive solar system materials is presented.

Comments: to be published in Advances in Geosciences

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0806.3103v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Steve Rodgers [view email]

[v1] Wed, 18 Jun 2008 22:49:27 GMT (1101kb,D)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0806.3103

A new type of comet found:

http://www.universetoday.com/2008/12/02/a-new-type-of-comet/

If it is our first confirmed comet visitor from another solar system,

we must send a mission to it.