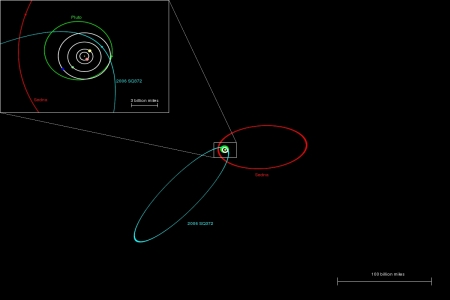

A symposium called Sloan Digital Sky Survey:Asteroids to Cosmology, held in Chicago this past weekend, is producing interesting news, not the least of which is the discovery of a ‘minor planet’ that is currently inside the orbit of Neptune. 2006 SQ372 is only in the neighborhood briefly, already setting out on a journey that will take it 150 billion miles from the Sun. Its orbit is an ellipse four times longer than it is wide, not dissimilar from the dwarf world called Sedna, which was discovered in 2003. But SQ372 strays even further out and takes twice as long to complete its orbit. You’ll need to click to enlarge the image below to see the details.

Image (click to enlarge): The orbit of the newly discovered solar system object SQ372 (blue), in comparison to the orbits of Neptune, Pluto, and Sedna (white, green, red). The location of the Sun is marked by the yellow dot at the center. The inset panel shows an expanded view, including the orbits of Uranus, Saturn, and Jupiter inside the orbit of Neptune. Even on this expanded scale, the size of Earth’s orbit would be barely distinguishable from the central dot. Credit: N. Kaib.

Is the new object actually an unusual comet? Andrew Becker (University of Washington), leader of the discovery team, calls it such, and adds that 2006 SQ372 simply never gets close enough to the Sun to develop a bright tail. Thirty to sixty miles across, the chunk of rock and ice was discovered and its existence confirmed through data originally taken to study supernovae, and the team behind the discovery has since been running computer simulations to make sense out of the object’s orbit. Says graduate student Nathan Kaib (also at UW):

“It could have formed, like Pluto, in the belt of icy debris beyond Neptune, then been kicked to large distance by a gravitational encounter with Neptune or Uranus. However, we think it is more probable that SQ372 comes from the inner edge of the Oort Cloud.”

The latter is an intriguing prospect. SQ372 is ten times closer to the Sun than the main body of the Oort Cloud, in which most objects are thought to orbit at distances of several trillion miles. The discovery of Sedna may have pointed to an ‘inner’ Oort region, and SQ372 could fit into that same picture. What’s likely to happen as we tune up next-generation surveys is that we’ll discover more and more objects of this class, giving us a better read on the population and distribution of this reservoir of icy materials.

Oort Cloud objects may in some cases be interstellar wanderers. We can imagine a process in the period of planetary formation four and a half billion years ago in which rocky materials were ejected from the inner system by the gravitational effects of the giant planets. A passing star could eventually dislodge some of these objects, causing them to move back into the inner system, where they would be visible as comets. Others might be ejected into interstellar regions, perhaps eventually falling into the gravitational grip of another star, cometary starships exchanging materials between distant solar systems.

It’s a pleasing thought, but we have much to learn before we can consider it definitive. As to 2006 SQ372 itself, its orbit ensures that a long time will pass before we have a closer look, 22,000 years in fact, and by then let’s hope we will have found ways to move among Oort Cloud objects at will, sampling, learning and exploiting their resources as we support a civilization with interstellar reach.

Both Sedna and 2006 SQ372 travel beyond the “solar focus” at 550 AU for part of their orbits – I wonder if any interesting target stars would be observable from these objects by using the Sun as a “gravitational telescope”.

What an interesting idea! I also wonder whether we can use this “solar focus point” to observe the core of our galaxy, this is much better than our ordinary space telescopes.

I (vaguely) remember having made this comment before in a long-ago thread so bear with me.

To land on an object like this you need to precisely match its velocity. That means the craft is already on the same orbit, and therefore the object is superfluous. Worse, that particular orbit constrains which interstellar objects we could observe – better to pick the observation targets first and the orbit second.

Further, assuming others are as impatient as I am, this is a slow way to get to 550 AU. I’d rather our gravitational lens observatory returned results in my lifetime.

On an different note, one SF novel (Lucifer’s Hammer, and I would not be surprised to hear about others in the same vein) posited a relatively large and unobserved minor planet in the Oort cloud (or maybe it was Kuiper belt) that every so often alters the eccentricity of other, smaller objects so that they pass into the inner solar system and cause havoc. In this novel one such object encounters Earth.

I was struck by just how much emptiness there is – vast amounts of nothing define the Borderland of Sol. Even if the Oort Cloud contains a trillion cometoids they will each have a sphere of void 10 AU in radius around them, on average. That’s mind-numbingly immense emptiness.

Somehow I suspect CR105, Sedna, SQ372, Eris are but the tip of the iceberg. I believe Alan Stern – principal investigator for New Horizons – shares a similar view. In the instance of CR105, Brian Marsden speculated that its disturbed orbit may have something to do with an as yet undetected mars sized body orbiting ~300 AU. Stern actually went a lot further by predicting an avalanche of up to Earth sized planets in the Oort Cloud awaiting discovery. The next decade or two could really be interesting.

Hi Shaun

Oligarchic planet formation theory predicts potentially dozens of Mars mass objects out there, and Al Stern has predicted potentially a thousand Pluto-sized objects. That’s a lot of real estate. But just what we can do with such in ours present energy challenged stage I’m unsure. Once fusion power becomes sufficiently well developed all those objects could become potential habitats.

A more SF idea I like to imagine is that wormholes could be developed as light-pipes and thus all those worlds would become viable. With wormholes also for rapid transit the Outer Solar System could potentially become more worth our colonisation efforts than the nearer stars if planet formation is as variable in its results as recent simulations suggest.

Isotropic Gamma-Ray Background: Cosmic-Ray Induced Albedo from Debris in the Solar System?

Authors: Igor V. Moskalenko, Troy A. Porter

(Submitted on 3 Jan 2009)

Abstract: We calculate the gamma-ray albedo due to cosmic-ray interactions with debris (small rocks, dust, and grains) in the Oort Cloud. We show that under reasonable assumptions a significant proportion of what is called the “extragalactic gamma-ray background” could be produced at the outer frontier of the solar system and may be detectable by the Large Area Telescope, the primary instrument on the Fermi Gamma-Ray Space Telescope.

If detected it could provide unique direct information about the total column density of material in the Oort Cloud that is difficult to access by any other method. The same gamma ray production process takes place in other populations of small solar system bodies such as Main Belt asteroids, Jovian and Neptunian Trojans, and Kuiper Belt objects. Their detection can be used to constrain the total mass of debris in these systems.

Comments: 4 pages, 1 figure, accepted by Astrophysical Journal Letters

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0901.0304v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Troy Porter [view email]

[v1] Sat, 3 Jan 2009 03:34:10 GMT (45kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0901.0304

Neptune Trojans and Plutinos: colors, sizes, dynamics, and their possible collisions

Authors: A.J.C. Almeida, N. Peixinho, A.C.M. Correia

(Submitted on 5 Oct 2009 (v1), last revised 9 Oct 2009 (this version, v2))

Abstract: Neptune Trojans and Plutinos are two subpopulations of trans-Neptunian objects located in the 1:1 and the 3:2 mean motion resonances with Neptune, respectively, and therefore protected from close encounters with the planet. However, the orbits of these two kinds of objects may cross very often, allowing a higher collisional rate between them than with other kinds of trans-Neptunian objects, and a consequent size distribution modification of the two subpopulations.

Observational colors and absolute magnitudes of Neptune Trojans and Plutinos show that i) there are no intrinsically bright (large) Plutinos at small inclinations, ii) there is an apparent excess of blue and intrinsically bright (small) Plutinos, and iii) Neptune Trojans possess the same blue colors as Plutinos within the same (estimated) size range do.

For the present subpopulations we analyzed the most favorable conditions for close encounters/collisions and address any link there could be between those encounters and the sizes and/or colors of Plutinos and Neptune Trojans. We also performed a simultaneous numerical simulation of the outer Solar System over 1 Gyr for all these bodies in order to estimate their collisional rate.

We conclude that orbital overlap between Neptune Trojans and Plutinos is favored for Plutinos with large libration amplitudes, high eccentricities, and small inclinations. Additionally, with the assumption that the collisions can be disruptive creating smaller objects not necessarily with similar colors, the present high concentration of small Plutinos with small inclinations can thus be a consequence of a collisional interaction with Neptune Trojans and such hypothesis should be further analyzed.

Comments: 15 pages, 9 figures, 6 tables, accepted for publication in A&A

Subjects: Earth and Planetary Astrophysics (astro-ph.EP)

DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/200911943

Cite as: arXiv:0910.0865v2 [astro-ph.EP]

Submission history

From: Alexandre Correia [view email]

[v1] Mon, 5 Oct 2009 21:11:27 GMT (1697kb)

[v2] Fri, 9 Oct 2009 11:23:44 GMT (1697kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0910.0865