The last time Cassini flew past Saturn’s moon Enceladus (August 11), temperatures over one of the so-called ‘tiger stripe’ fractures at the south pole were lower than had been measured on an earlier flyby in March. Two October encounters, one of them scheduled for today, may provide enough additional data to help us understand what’s going on. The fracture in question is known as Damascus Sulcus, which showed temperatures between 160 and 167 Kelvin in August, but 180 degrees Kelvin during the March flyby.

Then again, nothing about Enceladus should surprise us any longer, including an apparent change in the intensity of the plume, within which trace amounts of organics have been detected. The October 9 approach takes us to a distance closer than any previous flyby of a Saturnian moon, a mere 25 kilometers from the surface, a key objective being to study the composition of the plume with the spacecraft’s field and particle instruments. Thus Tamas Gambosi (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor):

“We know that Enceladus produces a few hundred kilograms per second of gas and dust and that this material is mainly water vapor and water ice. The water vapor and the evaporation from the ice grains contribute most of the mass found in Saturn’s magnetosphere. One of the overarching scientific puzzles we are trying to understand is what happens to the gas and dust released from Enceladus, including how some of the gas is transformed to ionized plasma and is disseminated throughout the magnetosphere.”

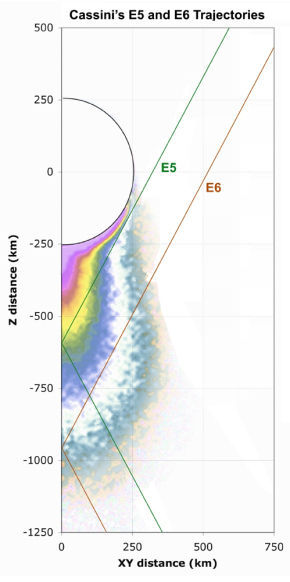

Image: This graphic shows the trajectories for the Cassini spacecraft flybys planned for Oct. 9 (E5) and 31, 2008 (E6). During Cassini’s Oct. 9 flyby, the spacecraft’s fields and particles instruments will venture deeper into the plume than ever before, directly sampling the particles and gases. The emphasis here is on the composition of the plume rather than imaging the surface. Image credit: NASA/JPL.

The October 31 flyby, closing to 196 kilometers, will image the tiger stripe region again, with both encounters offering the chance to find still further changes around this deeply interesting object. With four more Enceladus flybys planned for the next two years of the Cassini Equinox Mission — the name for Cassini’s extended mission — we can hope to learn more about what powers its geysers. We may also find clues to the moon’s past, since the different isotopes found in that environment could help to identify the temperatures at work during the formation of Enceladus.

Note: NASA’s Cassini flyby blog is now active.

to “venture deeper into the plume than ever before”…

Why do I get star trek flashbacks at this?

Hi Folks;

One can imagine that if there exists water or mineral laden aquious bodies under the Enceladian surface, and these bodies have existed for 4.6 billion years or a large fraction thereof, It would seem that the probability of finding even primitive animal life such as tube worms or simmilar creatures that are found near hydrothermal vents in Earth’s oceans, would be rather large.

Another class of organisms that comes to mind is the bacteria that exists in the hot springs of parks within the U.S. such as Yellow Stone and elsewhere that feed and live in a sulfurous high temperature aquious environment.

Depending on what the Cassini probe finds as it makes its next passes by Encelades will determine the rate of re-emphasis of our already extremely active robotic space program. This will give us even more knowledge which can facilitate manned excursion deep into the outer solar system and eventually beyond.

Thanks;

Jim

Ah… NASA publicity always sounds dramatic. Wonder how they’d handle the real thing?

November 3, 2008

Can Cassini be Used to Detect Life on Enceladus?

Written by Ian O’Neill

Having just returned the most detailed images yet of Saturn’s 500km-wide moon Enceladus, it is little wonder scientists are excited about this mysterious natural satellite. However, in new research recently published, the results aren’t related to the recent “skeet shot” Cassini carried out above the moon’s south pole (although there is some common ground). The paper’s origins started out in July 2005 when Enceladus’ plume of gas (containing organic compounds) was discovered fizzing from the moon’s surface, inside the “tiger stripes” just imaged by Cassini.

In some computer models, this plume is attributed to a sub-surface ocean. This possibility has led scientists to speculate that it might be an ideal environment for basic forms of life to thrive. What’s more, although the Cassini spacecraft isn’t equipped to directly search for life, it may be able to detect the signature of life…

Full article here:

http://www.universetoday.com/2008/11/03/can-cassini-be-used-to-detect-life-on-enceladus/