by Larry Klaes

Our fascination with ringed worlds continues to grow as we learn more about what circles the worlds of the outer system. If you’re looking for what may be the most spectacular ring system imagined — two ringed exoplanets locked in a tight gravitational embrace — be sure to read Jack McDevitt’s novel Chindi (Ace, 2003), and spend some time with his crew on the surface of the moon that orbits their center of mass. Meanwhile, join Tau Zero journalist Larry Klaes as he focuses on continuing revelations from Cassini about Saturn’s rings and the moons that feed them. And join us in our celebration of the extended Cassini mission. Who knows what discoveries await?

In the 1968 novel version of 2001: A Space Odyssey, author Arthur C. Clarke said that the magnificent rings of the gas giant planet Saturn were made by visiting advanced extraterrestrial intelligences who tore up some moons in the Saturn system in the process of making their incredible Star Gate. This artificial cosmic wormhole would ages later transport fictional astronaut David Bowman to another part of the Universe in order to transform him into “something wonderful.”

While most scientists are not inclined to believe or suggest that the rings of the second largest planet in the Solar System were made by some aliens on a construction project, they now think that Saturn’s rings were formed with the planet at the beginning of the Solar System roughly five billion years ago. Over the eons, moons would both smash into each other or be torn apart by Saturn’s massive bulk, creating the extensive rings we now see girdling the planet.

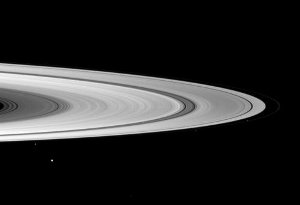

Image (click to enlarge): ”It’s full of stars!” David Bowman proclaimed in 2001: A Space Odyssey. This Cassini spacecraft view evokes the exclamation, ”It’s full of moons!” Credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute.

This process continues today. As the first space probe missions to Saturn discovered several decades ago, the rings are still being formed by a number of moons and even smaller moonlets, which contribute debris to the countless number of icy boulders and dust that make up the ring system.

There was one ring section that did not seem to have a moon or moonlet involved in its continued existence, the outer dusty ring labeled simply G. There was an extra collection of material at a certain point in the thin ring, but scientists operating the Cassini probe that is now entering its fifth year in orbit about Saturn had been unable to discover if the G ring had a companion world.

Now the Cassini imaging team, which include members of the Astronomy Department at Cornell University, have at last found the moonlet which supplies the debris for the G ring. The discovery was reported in the March 3 International Astronomical Union (IAU) Circular # 2093.

The moonlet, which has been given the provisional label of S/2008 S1 until an appropriate name from ancient mythology can be chosen, is the 61st known natural satellite for Saturn. This is just two less than the Solar System moon record holder, Jupiter, the largest planet in our celestial neighborhood.

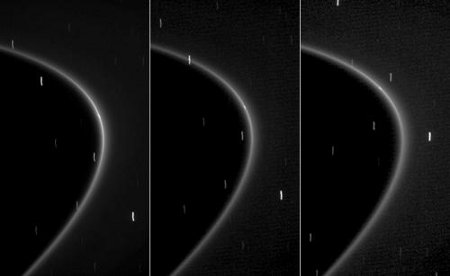

Image: This sequence of three images, obtained by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft over the course of about 10 minutes, shows the path of a newly found moonlet in a bright arc of Saturn’s faint G ring. In each image, a small streak of light within the ring is visible. Unlike the streaks in the background, which are distant stars smeared by the camera’s long exposure time of 46 seconds, this streak is aligned with the G ring and moves along the ring as expected for an object embedded in the ring. Credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute.

S/2008 S1 is deeply embedded in the main arc of the G ring. The moonlet’s very small size, only 600 yards across (Earth’s Moon is 2,160 miles in diameter, by comparison), explains why it eluded Cassini’s electronic eyes and those of its imaging team until now.

“Before Cassini, the G ring was the only dusty ring that was not clearly associated with a known moon, which made it odd,” said Matthew Hedman, a Cornell Cassini imaging team associate. “The discovery of this moonlet, together with other Cassini data, should help us make sense of this previously mysterious ring.”

Hedman and colleagues suspected that debris from collisions between micrometeorites and objects within the arc are the likely source for the material that makes up the G ring.

“We had evidence that there were big particles in the arc and thought that collisions between these objects and various micrometeoroids could release the dust that formed the ring,” Hedman said. “[This moon is likely] one of the objects that dust is knocked off of to form the ring.”

There may be other moonlets within the G ring arc, but S/2008 S1 is likely the biggest member of that group. Cassini will be able to photograph this region of Saturn again in 2010 and 2015 to get actual images of the moonlet and any companions in the arc. The discovery images of S/2008 S1 and others taken since then only show a faint smear of light, which is understandable considering the moonlet’s small size.

In addition to providing material to its ring, the little moonlet shares another feature with the other satellites that are involved with their rings: It and the arc are in resonance with a larger outer moon, in this case Mimas, which is best known for having one large crater that makes it look like the Death Star from the film Star Wars. The G ring is the second farthest ring system from Saturn at a distance of 100,000 miles.

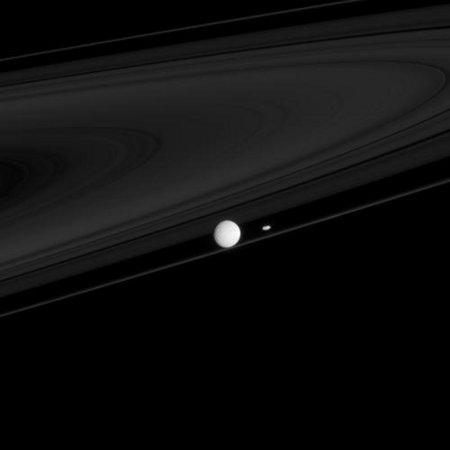

Image: Two other moons that have profound impacts on the rings, Mimas and Prometheus, are seen here with the F ring. Mimas (396 kilometers, or 246 miles across), the larger and much more distant of the moons, creates the Cassini division between the A and B rings. Prometheus (86 kilometers, or 53 miles across), although much smaller than Mimas, is half of a duo responsible for maintaining the narrow F ring. Credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute.

Last July Cassini was given a two-year extension on its mission and a resulting new designation: The Cassini Equinox Mission. The probe will do sixty more orbits of Saturn during that time, flying by the planet’s largest moon, Titan, 21 times to conduct further radar mapping of the bizarre and fascinating surface otherwise hidden beneath thick orange clouds. Cassini will also make seven close passes of Enceladus, the moon which the machine found to have active geysers spewing ice crystals into space. Both satellites are future targets for deeper exploration, in no small part to see if they are abodes for some kind of life.

cool stuff. ive read that saturns rings are somewhat complex, consisting of particles ranging from specks of dust to very small moons. (moonlet is a good descriptive word)

of course, titan is the best moon to investigate and consider for exploration, with its large size, bodies of liquid, hydrocarbons, dense atmosphere, and so on. and enceladus may have liquid water which demands a further look.

saturn is visible in the night sky from where i live in northern new jersey.. im gonna go out and look at it with a telescope.

Giant Ring Discovered Around Saturn?

NASA Science News for October 7, 2009

Just when you thought every big thing in the Solar System had already been discovered, NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope has found an extraordinary new “supersized” ring around Saturn.

FULL STORY at

http://science.nasa.gov/headlines/y2009/07oct_giantring.htm?list1094208

http://antwrp.gsfc.nasa.gov/apod/ap091013.html

Giant Dust Ring Discovered Around Saturn

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Univ. of Virginia

Explanation: What has created a large dust ring around Saturn? At over 200 times the radius of Saturn and over 50 times the radius of Saturn’s expansive E ring, the newly discovered dust ring is the largest planetary ring yet imaged. The ring was found in infrared light by the Earth-orbiting Spitzer Space Telescope.

A leading hypothesis for its origin is impact material ejected from Saturn’s moon Phoebe, which orbits right through the dust ring’s middle. An additional possibility is that the dust ring supplies the mysterious material that coats part of Saturn’s moon Iapetus, which orbits near the dust ring’s inner edge.

Pictured above in the inset, part of the dust ring appears as false-color orange in front of numerous background stars.

Aegaeon (Saturn LIII), a G-ring object

Authors: M.M. Hedman, N.J. Cooper, C.D.Murray, K. Beurle, M.W. Evans, M.S. Tiscareno, J. A. Burns

(Submitted on 1 Nov 2009)

Abstract: Aegaeon (Saturn LIII, S/2008 S1) is a small satellite of Saturn that orbits within a bright arc of material near the inner edge of Saturn’s G ring. This object was observed in 21 images with Cassini’s Narrow-Angle Camera between June 15 (DOY 166), 2007 and February 20 (DOY 51), 2009.

If Aegaeon has similar surface scattering properties as other nearby small Saturnian satellites (Pallene, Methone and Anthe), then its diameter is approximately 500 m.

Orbit models based on numerical integrations of the full equations of motion show that Aegaeon’s orbital motion is strongly influenced by multiple resonances with Mimas.

In particular, like the G-ring arc it inhabits, Aegaeon is trapped in the 7:6 corotation eccentricity resonance with Mimas. Aegaeon, Anthe and Methone therefore form a distinctive class of objects in the Saturn system: small moons in co-rotation eccentricity resonances with Mimas associated with arcs of debris.

Comparisons among these different ring-arc systems reveal that Aegaeon’s orbit is closer to the exact resonance than Anthe’s and Methone’s orbits are.

This could indicate that Aegaeon has undergone significant orbital evolution via its interactions with the other objects in its arc, which would be consistent with the evidence that Aegaeon’s mass is much smaller relative to the total mass in its arc than Anthe’s and Methone’s masses are.

Comments: 35 pages, 12 figures, submitted to Icarus

Subjects: Earth and Planetary Astrophysics (astro-ph.EP)

Cite as: arXiv:0911.0171v1 [astro-ph.EP]

Submission history

From: Matthew Hedman [view email]

[v1] Sun, 1 Nov 2009 20:39:35 GMT (3834kb,D)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0911.0171

The Sound of Saturn’s Rings:

http://www.universetoday.com/2010/01/20/the-sound-of-saturns-rings/

A Search for Water Masers in the Saturnian System

Authors: Shigeru Takahashi, Shuji Deguchi, Nario Kuno, Tomomi Shimoikura, Fumi Yoshida

(Submitted on 11 May 2010)

Abstract: We searched for H2O 6(1,6)-5(2,3) maser emission at 22.235 GHz from several Saturnian satellites with the Nobeyama 45m radio telescope in May 2009. Observations were made for Titan, Hyperion, Enceladus and Atlas, for which Pogrebenko et al. (2009) had reported detections of water masers at 22.235 GHz, and in addition for Iapetus and other inner satellites.

We detected no emission of the water maser line for all the satellites observed, although sensitivities of our observations were comparable or even better than those of Pogrebenko et al.. We infer that the water maser emission from the Saturnian system is extremely weak, or sporadic in nature.

Monitoring over a long period and obtaining statistical results must be made for the further understanding of the water maser emission in the Saturnian system.

Comments: 8 pages, 2 figures, accepted for publication in PASJ (Letter)

Subjects: Earth and Planetary Astrophysics (astro-ph.EP)

Cite as: arXiv:1005.1701v1 [astro-ph.EP]

Submission history

From: Shigeru Takahashi [view email]

[v1] Tue, 11 May 2010 01:47:57 GMT (135kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/1005.1701

Now if this isn’t an interstellar ark/generational ship leaving the Saturn system after collecting antimatter from its rings for its propulsion drive, then I just don’t know:

http://apod.nasa.gov/apod/ap101019.html

Okay, it isn’t, but that is what it reminds me of and it is a very cool image to boot.

Glittering ‘Mini-Jets’ Found in Saturn’s Curious F-Ring

by Nancy Atkinson on April 23, 2012

New images from the Cassini spacecraft have revealed kilometer-sized objects piercing through parts of Saturn’s F ring, leaving glittering trails behind them.

These trails in the rings, which scientists are calling “mini-jets,” provide insight into the curious behavior of the F ring, which Cassini imaging team leader Carolyn Porco called “Saturn’s most beguiling phenomena.”

With new detailed images, Cassini reveals the intricate workings of the F ring and hordes of tiny moonlet companions creating the trails.

“I think the F ring is Saturn’s weirdest ring, and these latest Cassini results go to show how the F ring is even more dynamic than we ever thought,” said Carl Murray, a Cassini imaging team member from Queen Mary University of London, England.

“These findings show us that the F ring region is like a bustling zoo of objects from a half mile [kilometer] in size to moons like Prometheus a hundred miles [kilometers] in size, creating a spectacular show.”

Full article here:

http://www.universetoday.com/94772/glittering-mini-jets-found-in-saturns-curious-f-ring/

9 April 2013

Text & Image:

http://keckobservatory.org/news/astronomers_using_keck_observatory_discover_rain_falling_from_saturns_rings

ASTRONOMERS USING KECK OBSERVATORY DISCOVER RAIN FALLING FROM SATURN’S RINGS

NASA funded observations on the W. M. Keck Observatory with analysis led by the University of Leicester, England, tracked the “rain” of charged water particles into the atmosphere of Saturn and found the extent of the ring-rain is far greater, and falls across larger areas of the planet, than previously thought. The work reveals the rain influences the composition and temperature structure of parts of Saturn’s upper atmosphere. The paper appears in this week’s issue of the journal Nature

http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v496/n7444/full/nature12049.html

“Saturn is the first planet to show significant interaction between its atmosphere and ring system,” said James O’Donoghue, the paper’s lead author and a postgraduate researcher at Leicester. “The main effect of ring rain is that it acts to ‘quench’ the ionosphere of Saturn, severely reducing the electron densities in regions in which it falls.”

O’Donoghue said the ring’s effect on electron densities is important because it explains why, for many decades, observations have shown electron densities to be unusually low at some latitudes at Saturn.

“It turns out a major driver of Saturn’s ionospheric environment and climate across vast reaches of the planet are ring particles located 120,000 miles [200,000 kilometers] overhead,” said Kevin Baines, a co-author on the paper, based at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif. “The ring particles affect which species of particles are in this part of the atmospheric temperature.”

In the early 1980s, images from NASA’s Voyager spacecraft showed two to three dark bands on Saturn and scientists theorized that water could have been showering down into those bands from the rings. Those bands were not seen again until 2011 when the team observed the planet with Keck Observatory’s NIRSPEC, a unique, near-infrared spectrograph that combines broad wavelength coverage with high spectral resolution, allowing the observers to clearly see subtle emissions from the bright parts of Saturn.

The ring rain’s effect occurs in Saturn’s ionosphere (Earth has a similar ionosphere), where charged particles are produced when the otherwise neutral atmosphere is exposed to a flow of energetic particles or solar radiation. When the scientists tracked the pattern of emissions of a particular hydrogen molecule consisting of three hydrogen atoms (rather than the usual two), they expected to see a uniform planet-wide infrared glow. What they observed instead was a series of light and dark bands with a pattern mimicking the planet’s rings. Saturn’s magnetic field “maps” the water-rich rings and the water-free gaps between rings onto the planet’s atmosphere.

They surmised that charged water particles from the planet’s rings were being drawn towards the planet by Saturn’s magnetic field and neutralizing the glowing triatomic hydrogen ions. This leaves large “shadows” in what would otherwise be a planet-wide infrared glow. These shadows cover 30 to 43 percent of the planet’s upper atmosphere surface from around 25 to 55 degrees latitude. This is a significantly larger area than suggested by the Voyager images.

Both Earth and Jupiter have a very uniformly glowing equatorial region. Scientists expected this pattern at Saturn, too, but they instead saw dramatic differences at different latitudes.

“Where Jupiter is glowing evenly across its equatorial regions, Saturn has dark bands where the water is falling in, darkening the ionosphere,” said Tom Stallard, one of the paper’s co-authors at Leicester. “We’re now also trying to investigate these features with an instrument on NASA’s Cassini spacecraft. If we’re successful, Cassini may allow us to view in more detail the way that water is removing ionized particles, such as any changes in the altitude or effects that come with the time of day.”