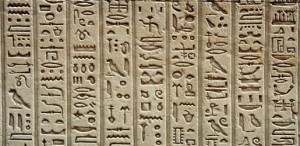

I once had an uncle who, in his eccentric way, taught me the glories of reading widely and across many disciplines. Every year he would visit us from Florida and each time he came, he was off on another tangent, usually a scientific pursuit of some kind, and now and then a venture into linguistics. One of his more memorable visits found him arriving with a set of slides he had made from books on Egyptian hieroglyphics, and we went through them one at a time as he explained what he had learned about Egyptian culture by mastering these symbols.

Hieroglyphics Meet the Machine

I think about that every time I ponder the fate of digital data, and this Reuters story, which mentions hieroglyphics, triggered the memory. For as Andreas Rauber (University of Technology of Vienna) points out, hieroglyphics — or, for that matter, stone inscriptions or medieval manuscripts — have a shelf life of millennia, and have proven it. In my own wandering way, I was for a time focused on medieval manuscripts and recall wonderful moments at the British Museum and the Háskóli Íslands (Reykjavík) studying documents that recorded the stories, as well as the daily business and musings, of societies a thousand years old.

There’s a fascination in working out the conventions of a medieval scribe, but in the modern world, we have an equally thorny task in sorting out digital formatting. We live by data in our time. 100 gigabytes of data (the article points out this is equivalent to about 23 tons of books) have been created for every individual on the planet, and Adam Farquhar (British Library) notes that this amounts to about a trillion CDs worth of data spread across the globe. Farquhar and Rauber are worried about our continuing access to these data. Says Farquhar:

“Einstein’s notebooks you can take down off the shelf and read them today. Roll forward 50 years and most of Stephen Hawking’s notes will likely only be stored digitally and we might not be able to access them all.”

International Data Corporation says the size of the digital universe will expand by ten-fold, from 161 billion gigabytes (exabytes) in 2007 to 1800 exabytes in 2011. The figure is predicted to double every eighteen months. Yet amidst the data avalanche, we live in a world where CDs and DVDs have an exceedingly short life expectancy and many data backups may simply fail when the time comes to access them. We’re learning how to spread the backup into the ‘cloud’ of networked computers, but haven’t solved the many security issues that involves.

Preserving Changing Formats

Even more telling is the fact that we continue to change data formats seemingly at whim. Change that improves things is always welcome, but our digital rush to the future often seems to move to its own whimsical music. Trying to upgrade the software I use for Centauri Dreams, I find that the new version’s coders have re-written key aspects of the programming environment, so that all the formatting I put into the header design would simply fail if I made the ‘upgrade’ without digging into the code myself and making a set of manual fixes.

Well, I’ll do all this because new features are available (and be aware of this in the next week or so if the site suddenly starts acting strangely), but there is such a thing as backwards compatibility. And this is the tiniest of problems compared to what decades, not to mention centuries, of ongoing change could do to data stored cavalierly because access is assumed.

What Rauber and Farquhar intend to do about all this is to preserve a ‘digital genome’ deep in the Swiss Alps in a secret bunker, where the needed information to read all our formatting is made available to future generations. The sealed box is buried somewhere near the town of Gstaad, in a data facility known as the Swiss Fort Knox in the Bernese Oberland, an installation that consists of two underground data centers that are 10 kilometers apart but connected by high-speed networking. The facility is in a former military nuclear bunker designed to offer physical protection against all manner of environmental disasters.

Going Deep in Switzerland

Behind the burying of this ‘digital genome’ is the Planets project, which links European libraries, archives and research institutions in an attempt to preserve both software and hardware assets as older versions of each are superseded. Inside the box are at risk digital formats, from JPEG photographs to messages in Java, films in .MOV format and documents in PDF. Here’s how the project describes the contents of the Planets TimeCapsule:

Each object is stored in its original format and a new format more suitable for long-term preservation such as PDF/A, TIFF, JPEG2000 and MPEG4. The objects are stored on media that range from paper, microfilm and floppy discs to CDs, DVDs and flash-drives and HDDs.

Inside the box are the original and new objects, storage media, and some reading devices. It also includes conversion tools that were used to migrate the objects as well as software to open and view/use these objects and supporting software all the way down to an operating system; descriptions of the file formats, of the file systems and encodings used on the storage media; and description of all these objects and their relationship to supporting technology and recognised standards.

And yes, an online version is to be provided, while replicas will be available to libraries, archives, science museums and other interested parties. The need will surely grow for it to be augmented on a regular basis as our formats continue to sprout changes and extensions. Anyone who has been using computers for a sufficient time will be aware of how acute this issue can be. I think of the hundreds of articles, reviews and columns I wrote in the 1980s using the now defunct XyWrite program, which began with straight ASCII data formats but gradually changed so that its files were unreadable without the program. I would have to locate some very old software if I had a need to get into the digital versions of all this work today.

For more about the Planets project, you can download a brochure here. I notice that it’s in the baleful PDF format, all but universal for the dissemination of scientific papers, yet balky and bloated and forever at the mercy of Adobe. Every digital ‘upgrade’ has its advantages, or at least most of them do, and getting the most out of our data is in the hands of good coders, but as our bits and bytes head inexorably into the future, we’d better hope that data preservation eventually becomes built into every operating system we run on our machines, and that the future web of interconnections keeps the knowledge of past formats always at hand.

The U.S. National Archives has its own electronic data preservation project:

http://www.archives.gov/era/about/faqs.html#era

This may sound cynical, but I’ll take the risk. The vast bulk of what is now is digital format isn’t worth saving. The very fact that much of it is dying off because it’s still, only, on obsolete formats (hardware and software) is a partial demonstration that no one has seen the value in propagating it forward.

There are always gems in the past whose value we fail to recognize before it is too late, however I would argue that I can accept the loss of a few gems if we can keep the noise level down to a manageable level. After all, a good way to improve the chance of finding a “signal” in the historical record is to reduce the noise. The historians among our descendants might appreciate a low noise level when they mine our data record.

Failure to design survivability into digital media borders on criminal!

The Long Now Foundation http://longnow.org is proposing microscopic etching onto durable metal, reading these would require only a magnifying glass, and they will last for 10,000 years.

Most books ever written are not read now, but they could be if anyone wanted to. There’s a difference between unread and unreadable.

No simple solutions here. The best, but imperfect steps for preserving data are:

1) relevance and use, give people a reason to invest in data preservation.

2) open formats. Keep data in formats that are open, nonproprietary, and cross-platform. XML and the like are good for more structured data, since it’s just ASCII.

3) LOCKSS. “lots of copies keeps stuff safe”. Make data open enough to be freely and legally copied. It’ll give lots of backups, permit people to find ways in which data can be relevant and used, and will be more likely to enter a digital repository. Strong “fair use” permissions need to exist allowing libraries to do their jobs (lots of scientific knowlege is rented from publishers, and libraries don’t archive these papers because they’d get sued for copyright infingement). If you have data/content you want to preserve, fight for fair use and library rights and license your content with Creative Commons licences.

Data rot is a very serious issue. It’s great that steps are being taken to secure digital mediums for the long-term. As I’ve mentioned previously, there are also DVDs which have an obsidian-like hard layer which is scratched by a laser in order to preserve data. Most CDs/DVDs on the other hand have a limited shelf life, and even better ones will fade after several years.

I strongly disagree with your sentiment. While there is lots of junk on the internet, there is plenty of digital information that is worth saving or is of interest now or in the future.

One of the biggest problems facing historians is a lack of data. As you look back in time, sources become scarce, so even our best scholarly views of ancient civilizations are put together from fragments. An idiot living in Ancient Rome knows more about that culture in his time and place than some of the leading scholars today. Eventually, our media will be of great interest, even that which doesn’t seem as important. And there are numerous other types of data which are useful for historical record – for example, if we had accurate climate reports going back centuries, that would make a strong impact on the global warming debate.

Another advantage of digital media is that it can be very well organized and easy to sort through. It’s not too much of a hurdle to have encyclopedias of information when you can quickly search through them. So, that also helps negate the noise factor.

Reading and Writing are two of the most important human abilities. It would be a very worthwhile pursuit to preserve our writing (in its many forms).

That’s why print will never die, despite the claims for it. All I need are my eyes and light. Digital media is by its very nature ephemeral and perversely requires a lot more gear to utiilize: if you don’t have the proper machine or format decoder, you may as well not have the material at all. I’m pretty sure we all have something – on floppy, betamax, punch cards – that is almost irretrievable with 10 to 15 years. The pace of obsolescence is only increasing. I wonder how much knowledge is lost as it does so.

As I read this, my husband commented on a job interview he had circa 1995 at the Smithsonian Institute. He is an electron microscopist, the job he was interviewing for was running the Scanning EM in the History Museum. They asked him about his opinion on the use of digital data as using digital imaging was a new, hot ticket item in microscopy. They wanted all their imaging done digitally. He told them that digital imaging was convenient for quick sharing of the information and efficient for storage, especially in facilities with limited space. However, it has a finite life and and formats change, thus making hard copies would still be an important part of any long-term storage. Of course, they didn’t like what he said and he didn’t get the job. But he was right.

In my very humble opinion, I think this is a crucially important editorial that needs to be spread beyond the scope of this forum.

It is not just the data formats that are ephemeral, but the very substrate of technology they are built upon. In my line of work – safety critical control systems – we frequently encounter contractual obligations to support systems for a lifespan of 20 or more years. On paper this sounds simple, and our sales people happily sell our ability to perform this support. The reality is very different – by the time we have selected a processor, prototyped or sourced hardware, ported existing or written new application software, passed through verification & validation, integrated the system in the customer environment, passed customer acceptance testing, and reached full scale deployment we usually find that our designs are already obsolescent. Twice in my career we have had to re-engineer before even reaching product roll-out, after finding that a key component had vanished off the market and we needed to re-engineer around its replacement. Far more often we find that less that halfway through a product’s lifecycle we are performing “end of life” buys of components to lay in a supply of spares for support. My current project in fact started as a “crash priority” port of an application from an old 68K based embedded platform to state of the art PowerPC based hardware because we simply could not build replacement builds any more.

The major cause is that consumer electronics are the primary market driver. It doesn’t matter if a component in this year’s mobile phone, TV, whatever, is obsolete, because next year there will be a bigger / better / cheaper version. For those of us building applications for the long term, it creates a nightmare. We cannot code any application with a certainty that in 5 or 10 years time we’ll be able to build the hardware on which it depends, and each time we get forced to port or re-develop a little more of our back compatiblity is lost.

Even the language standards themselves keep moving on … Ada 83, to Ada 95, to Ada 2005 – each step an “upgrade” that broke some older code, forcing it to be modified. In C & C++ the same deal … the draft C++ standard currently in progress does not much resemble the language I first learnt 20 years ago. Even getting a 10 or 20 year old chunk of source code to compile, and then to run correctly, can be battle.

Now, consider that these experiences come from a career in software engineering spanning only 25 years so far. Scale it up to 50, or 100 years, and the difficulties in preserving anything are daunting …

… unless we start defining true long term storage formats and freezing the technology to write and read them as international standards.

bigdan201:

“I strongly disagree with your sentiment. While there is lots of junk on the internet, there is plenty of digital information that is worth saving or is of interest now or in the future.”

I did not say anything to contradict this. Please re-read what I said.

“One of the biggest problems facing historians is a lack of data.”

I am not willing to make a large investment *today* to satisfy the curiosity of distant historians. Preserving all or most everything is expensive. Who pays, today? You may be willing to pay, but I am not.

” …if we had accurate climate reports going back centuries, that would make a strong impact on the global warming debate.”

Again, if data is valuable it will be preserved. Yours is an example of valuable data, and today’s data are being preserved. “Accurate climate reports going back centuries” don’t exist because they weren’t made, not because they rotted or were erased.

Ron S: “The vast bulk of what is now is digital format isn’t worth saving.”

I have read this several times before, but always without examples. Because you say, it’s the “vast bulk” — a venturesome statement, I think –, it shouldn’t be difficult for you to list three or four examples. Would you mind …

Alright, but your post suggested to me that you have a different idea of how much digital data should be preserved. It seems to me that many things are taken for granted which shouldn’t be, whether its media, creative works, records, and so on. Whether it’s for cultural reasons, or in the interest of future research and databases, it would pay off greatly in the long run to find a reliable, cost-effective, and consistent method of long term digital storage.

The fact that so much data is stuck on obsolete formats isn’t because no one values it, but because not enough efforts have been made to preserve digital data in general. To go on a minor tangent, people are at work trying to preserve old black&white film, since the celluloid deteriorates over decades. It’s not that no one cares about them, the issue just wasn’t addressed until data rot set in significantly.

We will want to preserve lots of our stuff, the issue here is not taking storage for granted and finding solutions for data rot. Too many people have assumed that you can simply put something on a disc or drive and leave it there, only to be unpleasantly surprised by data rot.

I don’t favor going to great expense to preserve digital data. I believe that we can and should find a cost-effective, consistent solution for long-term data storage – once that is in place, everyone else will do the rest. Once people are aware that current digital records fade, they will want to maintain our information for posterity. Once that better mousetrap is built, everyone will come running.

On top of that, given the short lifespan of many digital mediums, data rot will affect us in our own lifetimes if it is not addressed.

Indeed. I was simply giving an example of undeniably valuable data that we would not want to lose to data rot. While climate reports were not written in centuries past, it is likely that there were valuable things recorded that were lost to time. When you consider the wealth we’ve gotten from monks in the middle ages, we can only speculate as to how much was not passed down.

Possible technology for a new type of flash drive storage, which lasts *one billion years*:

http://nextbigfuture.com/2009/05/nanoscale-reversible-mass-transport-for.html

Duncan:

” Ron S: “The vast bulk of what is now is digital format isn’t worth saving.”

I have read this several times before, but always without examples. Because you say, it’s the “vast bulk” — a venturesome statement, I think –, it shouldn’t be difficult for you to list three or four examples. Would you mind …”

Sure. Each of our comments on this blog. They may matter to you and me right now in this moment, but I very much doubt they would have any value even to us within 48 hours. Therefore, why go to any effort to save this data?

A key thing to remember here is value, which I’ve already mentioned. Value is purely subjective. Someone has to value something enough to archive it, and then others have to value it enough to keep the archive viable into the future. This chain is easily broken. Allocating resources to archiving requires the perception of value to those allocating those resources.

You might value these comments more than I do. Fair enough. But to be archived more than a short time after the demise of this blog (and it will have to end eventually) will require someone somewhere to begin the allocation of resources to its preservation. As much as I love this blog, I have to predict that in, say, 2050, its value will be very low indeed to those who much preserve the archive.

bigdan201:

“Alright, but your post suggested to me that you have a different idea of how much digital data should be preserved.”

As I mentioned to Duncan, value is subjective. What I think doesn’t much matter; I wasn’t attempting to impose upon you, but rather to make what I think is a fair prediction. You yourself gave examples where others did not value, or did not value enough to spend the money, to preserve certain records that you value.

“The fact that so much data is stuck on obsolete formats isn’t because no one values it, but because not enough efforts have been made to preserve digital data in general.”

The reason it’s obsolete is because no one saw the value in up-converting the data. Whimsy or nostalgia doesn’t count, unless it motivates those who own the data (much of it is privately owned) to spend money to preserve it, or willing to sell to others who will spend the money to both buy and preserve the data. And this is for publicly-known data only, not data that is locked behind corporate and government firewalls due to its proprietary or sensitive nature.

“I believe that we can and should find a cost-effective, consistent solution for long-term data storage…”

I fully expect that we will, but not that it will be universally employed since resources must be allocated by those, if any, who value the data to be archived. Heck, I can even imagine an AI curator in the future that is tasked with archiving. Then we come back to that noise problem I mentioned in my first comment; searches could become very painful even with future technology and search algorithms. I find it hard enough today to get on Google or other search engines and come up with searches that don’t flood me with irrelevant noise.

“When you consider the wealth we’ve gotten from monks in the middle ages, we can only speculate as to how much was not passed down.”

Indeed. Although the monks were a special case in that many had little to do other than copy and distribute data. Regrettably, the past is full of illiterates who could not record except through word of mouth. Many cultures have a rich oral tradition that is now dying out, and there are people working fast to archive those old stories and languages.

In closing, I was and am not attempting to be pugnacious on this topic; I am only trying to point out some real impediments that will be encountered by those who dream of recording everything and making it future-proof.

Indeed, I can see exactly where you’re coming from. There are some definite limitations and obstacles in recording everything for posterity… I’m still optimistic that it can be done effectively, if not perfectly.

As far as noise, that is a consideration, although with better organization and search algorithms it will become more manageable. Although it will be problematic in especially large and detailed archives, I believe it can be handled with good archival work.

Economics, as always, is an important shaping factor. But there is another point to consider – data becoming eroded or obsolete is not always because no one saw the value of maintaining it. Many people simply aren’t aware of data rot, or don’t take into account rapidly changing formats, until it is too late. Like my example with old b&w movies, people did archive them and value their existence, and only recently realized that their data is breaking down. A similar situation happens with hard drives and discs and so on.

Once people are well aware of data rot and formatting issues, and once a viable alternative is widely available, the situation will improve quite a bit.

I am optimistic of peoples’ willingness to preserve data of value.

The fact that oral tradition is in such a precarious state illustrates why reading & writing is one of the most valuable tools we have. The invention of writing was, in my opinion, one of the Five Great Revolutions in my view of history.

I look forward to being able to preserve our digital writing and digital creations on the same time-scale as stone tablets or the Parthenon.