Because I’m immersed in Laura Snyder’s wonderful book The Philosophical Breakfast Club (Broadway Books, 2011), I’ve been thinking lately about William Whewell. Long the master of Trinity College, Cambridge, Whewell helped bring sound, inductive methods to the fore in the science of his day, created models of international cooperation in scientific investigations through his studies of the tides, founded the discipline of mathematical economics, studied crystallography and, in one memorable episode, became involved in a 19th Century imbroglio over alien life.

This morning I want to focus on that incident, but it’s just one of the numerous episodes Snyder recounts in her history, which follows four remarkable men — Whewell, mathematician Charles Babbage, astronomer John Herschel (son of William) and economist Richard Jones — through a lifetime of friendship and scientific inquiry. What’s fascinating about Whewell’s brush with the topic of extraterrestrial life is that it reveals how widespread was the idea of such life in the 19th Century. Indeed, Whewell’s problem was that he came around to skepticism about life among the stars, a position all but unthinkable to many in the scientific community of his day.

A 19th Century Read on Extraterrestrial Life

In the late 1850’s Whewell (pronounced ‘HOO-ell’) had a bestseller on his hands in the form of a book called Of the Plurality of Worlds. The book was a sharp departure from his earlier work some twenty years before, when he had argued for the possibility that other stars might have planets with intelligent life on them. The new book argued against the idea of intelligent life anywhere but the Earth, prompting scathing attacks from some reviewers. Here’s one critic who sees Whewell in positively medieval terms:

We scarcely expected that in the middle of the nineteenth century, a serious attempt would be made to restore the exploded idea of man’s supremacy over all other creatures in the universe; and still less that such an attempt could have been made by one whose mind was stored with scientific truths. Nevertheless, a champion has actually appeared, who boldly dares to combat against all the rational inhabitants of other spheres; and though as yet he wears his visor down, his dominant bearing, and the peculiar dexterity and power with which he wields his arms, indicate that this knight-errant of nursery notions can be none other than the Master of Trinity College, Cambridge.

So wrote one reviewer in the London Daily News. I was startled when reading this section of Snyder’s book to learn just how common, and accepted, the idea of extraterrestrial life was in the mid-19th Century. One David Brewster, who was driven almost to apoplexy by Whewell’s new book, took on the master of Trinity with a will, arguing that life was to be found just about everywhere. Brewster maintained that Jupiter was inhabited by beings with ‘a type of reason of which the intellect of Isaac Newton is the lowest degree.’ And he was hardly alone. Here’s Snyder on the matter:

Ever since Copernicus had shown that the earth was not the center of the universe, but just a planet circling the Sun like all the others, most people assumed that other planets could, like earth, contain intelligent life. This notion that there was a ‘plurality of (inhabited) worlds’ had even become an accepted tenet of natural theology, it being believed that empty planets, devoid of life, would indicate wastefulness on the part of God. Why would God have created so many worlds, if not to be the seats of life? Babbage had ended his book On the Economy of Machinery and Manufactures with a rhapsodic depiction of the vastness of our universe, filled with so much life: as all these planets and moons and stars were ‘the work of the same Almighty Architect,’ he argued, it was not credible that ‘no living eye should be gladdened by their forms of beauty, that no intellectual being should expand its faculties in deciphering their laws.’

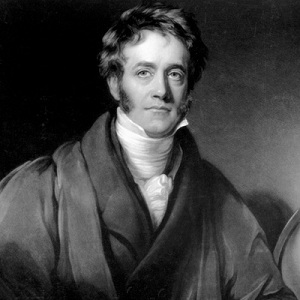

Solar Beings, and Bat People on the Moon

For his part, astronomer John Herschel often speculated on intelligent life in the cosmos and believed for a time that there were rational beings living on the Sun, as well as on the planets and their various moons. The odd belief about life not near but on a star echoed Herschel’s father William, who argued that below its hot atmosphere, the Sun had a surface cool enough to support life. John Herschel’s Treatise on Astronomy (1833) made the case for some of these views, and was picked up by one Richard Adams Locke, who created a series of articles for the New York Sun out of whole cloth in 1835, claiming that Herschel had observed bat-like men on the Moon, not to mention horned bears and bipedal beavers, through a fabulous new telescope.

Image: John Herschel in the 1830s, from a portrait by H.W. Pickersgill.

The story took off in the press while an oblivious Herschel was working at an observatory on the Cape of Good Hope, with the American writer Edgar Allan Poe calling the series of articles ‘decidedly the greatest hit in the way of sensation…ever made by any similar fiction.’ The uproar over the hoax finally settled down, although an exasperated Herschel, who said he was ‘pestered from all quarters with that ridiculous hoax about the Moon,’ never stopped believing that intelligent life was widespread in the universe. He did, however, give up on the idea of life on the Sun.

Whewell is the one who stands out in all this, however, because the tenacity of the attacks on him, especially those of David Brewster, neatly made the point he wanted to make. Whewell was, above all, a believer in the need for proper scientific method, and the need to educate the public in its workings (his History of the Inductive Sciences was a major influence on Darwin). This is the man who coined the word ‘scientist,’ a man who believed in finding evidence rather than merely making assertions, and he rightly pointed out the problems with the idea of intelligent life on places like Jupiter which, given the astronomical knowledge of the day, seemed anything but hospitable to it. He would also argue the case of extraterrestrial life from the standpoint of natural theology, but he never confused the latter with scientific method.

A famous slur on Whewell says that his book was an attempt to show that ‘through all infinity, there was nothing as great as the Master of Trinity.’ But even though we have far different views about life in the universe today — and with the kind of painstaking science Whewell believed in, we are learning more every day — the fact remains that the enthusiasm for extraterrestrial life Snyder depicts in the early Victorian era was more like a popular mania than a sustainable belief. We still don’t know whether there is intelligent life on other worlds, though we’re taking the best steps we can to learn, but the history of our fascination with extraterrestrials is instructive. It tells us that while enthusiasm is infectious, we have to keep our eyes on the prize: Reliable data.

Breakfasts to Remember

The Philosophical Breakfast Club is a gem, and anyone interested in the history of science or the cultural realm of 19th Century Britain will find it absorbing. I haven’t had time here to do more than sketch an episode that should intrigue Centauri Dreams readers, but realize that Snyder gets into Charles Babbage’s obsession with building the kind of machinery that would turn into today’s computers, and Herschel’s contributions not only to astronomy but to photography and even botany, while the little heralded Jones is shown as a poorly disciplined but highly talented man who shaped our modern understanding of economics. These four interacted from the 1810s to the 1870s, driven by science and a common passion to change the world.

The breakfast club? Babbage, Herschel, Jones and Whewell began to meet on Sunday mornings after chapel services at Cambridge in 1812, when they were all students there. I have to pass along Snyder’s description of the kind of breakfasts the four young men consumed:

When the men arrived, they were relieve to find a roaring fire that had been prepared by Herschel’s ‘gyp,’ or college servant. The mornings during term time were typically cool and damp, and in the winter it was still dark. As they took off their robes and warmed themselves, Herschel would motion for his gyp to go to the kitchen of the college and retrieve the bountiful breakfast he had ordered: tea, coffee, and ‘audit ale,’ so called because it was the best beer, by tradition reserved for the feast or ‘audit’ days; tongue, cold beef, ham, chicken, anchovies, and eggs; toast, muffins, crumpets; honey, marmalade, and butter (which was shaped into rolls an inch in diameter and sold in town by inches, ‘measured out by compasses, in a truly mathematical manner,’ as the novelist Maria Edgeworth put it after a visit to Cambridge around this time).

Imagine doing anything but sleeping after a repast like that! But these four would then go on to discuss the topic of the week, often one of the writings of Francis Bacon (1561-1626), whose great belief was that science could be used to change the fabric of society and improve peoples’ lives. And as Bacon wanted to find a logic applicable to both the study of nature and the study of men, an all-encompassing logic, so the four young Cambridge students would spend their lives looking for ways to promote and encourage the new science. Their rivalries, intrigues and passions in a lifetime of dedicated research take on vigorous life in Snyder’s expert hands.

People interested in Philosophy and the Extraterrestrail Life Debate can have a look at “The Extraterrestrial Life debate in different cultures”

available at http://fr.arxiv.org/abs/1003.0277

Jean Schneider

Arthur Clarke had a remarkable story of solar life in “Out of the Sun”. Though it was before Mercury’s true rotation was determined, it is thought-provoking. He briefly returned to the subject in “The Lost Worlds of 2001”.

Jean Schneider writes:

I appreciate this tip, because I wasn’t aware of your 2010 paper. Looking through it, I’m now planning a Centauri Dreams entry discussing some of your findings. Thanks very much, Dr. Schneider!

That was some group of undergraduates! John Herschel was a superstar of Victorian science (Darwin made the HMS Beagle stop at the Cape Colony in South Africa just to meet him). At Cambridge, Herschel, Babbage and Peacock founded the Analytic Society that revitalized British mathematics.

Wish I could have been there to listen to some of those discussions.

Dear Mr. Gilster:

Thank you for the very interesting column you wrote about the “Philosophical Breakfast Club.” I was ESPECIALLY interested in how the astronomer John Herschel used to believe rational beings could some how live on or in the Sun. I was immediately reminded of how Poul Anderson used exactly that idea in his short story “Kyrie” (which can be found in his collection GOING FOR INFINITY (2002), but originally published in 1968. Anderson speculated such a being would be mostly a plasma vortex and communication with others would be by telepathy.

Sincerely, Sean M. Brooks

I shall recommend you 2 books: “The Lunar Men” and “The Age of Discovery” :)

http://www.amazon.com/Lunar-Men-Jenny-Uglow/dp/0571216102/ref=sr_1_2?ie=UTF8&qid=1301246439&sr=8-2

http://www.amazon.com/Age-Wonder-Romantic-Generation-Discovery/dp/1400031877/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1301246517&sr=1-1

Regards.

A couple of you here bring up the idea of plasma life within the sun. As such it was described as a plasma vortex by Sean. My understanding is that such a form would have to be built from knots in magnetic field lines of such vortices. To me each knot should be more reprehensive of an atom within chemistry than a molecule. Does anyone have an estimate of how big such hypothetical life would need to be?

Dear Mr. Henry:

Thanks for your comments. I should tell you right away that I’m not a physicist or scientist, merely an SF fan. So, I could not say how a rational being which was a plasma vortex could be built from knots in a magnetic field.

With Mr. Gilster’s indulgence, I’ll quote Poul Anderson’s speculationss from “Kyrie” on how such living beings could have evolved on or near stars: “He hugged scientific explanations to his breast, though they were little better than guesses. In the multiple star systems of Epsilon Aurigae, in the gas and energy pervading the space around, things took place which no laboratory could imitate. Ball lightning on a planet was perhaps analogous, as the formation of simple organic compounds in a primodial ocean is analogous to the life which finally evolves. In Epsilon Aurigae, magnetohydrodynamics had done what chemistry did on Earth. Stable plasma vortices had appeared, had grown, had added complexity, until after millions of years, they became something you must needs call an organism. It was a form of ions, nuclei, and force fields. It metabolized electrons, nucleons, X rays; it maintained its configuration for a long lifetime; it reproduced; it thought.”

And in the preceding paragraph, Anderson described such a plasma vortex which was also a ration being “as a fireball twenty meters across.” But really, it’s best for interested readers to look up and read the entire story!

Sincerely, Sean M. Brooks

Sean, if the ratio of the size of your proposed organism to the potential size of its component knots is correct, then I can finally understand my granny’s obsession with knitting. She wasn’t trying to create jumpers for her grandchildren at all: she was trying to create life!

The smallest bacteria are a fraction of a micrometer, or not much more than 1000 times the size of a small molecule. I have no idea what size these “plasma knots” would be, if they exist, but you could certainly imagine life forms just 1000 times bigger. They would not be “thinking”, though….

Plasma physics sure is complex enough to support this sort of speculation, but I do not think there are any established real candidates for these “knots”. Unless someone could enlighten me?

The very concept of plasma-based life living in stars shows how much we have yet to discover and learn and how limited SETI is in certain respects. Though searching away from Sol-type suns and checking out infrared sources in the colder outer regions of the galaxy is a start.