Imaging an Earth-like planet in the habitable zone may happen some time in the next decade if the James Webb Space Telescope can make its way through its budgetary hurdles and achieve a 2018 liftoff. But the word ‘imaging’ is a bit deceptive when you consider that we won’t be getting anything remotely like the view of a planet in our own Solar System through Webb’s instruments. No small disc with discernible features, in other words, but a single dot useful not because of what we can pick out visually, but because we can use its light to take a spectrum. And if we’re really lucky, we’ll find a dot that’s blue and a spectrum that shows the signature of a living world.

The JWST works at infrared wavelengths (covering a range from 0.6 to 28 micrometers), which is why shielding it from heat is so important, and why the design is marked by a large sunshield. These wavelengths should allow the instrument to study stars and galaxies from the early universe, but the addition of a starshade to the mission concept would enhance the exoplanet part of the conversation. In a recent Astrobiology Magazine article, Leslie Mullen talked to Matt Mountain and John Grunsfeld (Space Telescope Science Institute) about what a starshade might do (thanks to Erik Anderson for the tip). Think of a disc tens of meters wide with petal-like extensions placed between telescope and star. Mountain likened the starshade to putting your thumb in front of the Sun to create shadow:

[The starshade is] very carefully shaped, so you don’t get the sort of flaring that you normally get when you use a perfect sphere, where you get all these rings and refractions. These petals are designed to create a very smooth, very deep shadow. You basically slide in and out of the shadow, and then you can actually see the planet next to the star. The star is in the shadow, and the planet peeks around the shadow.

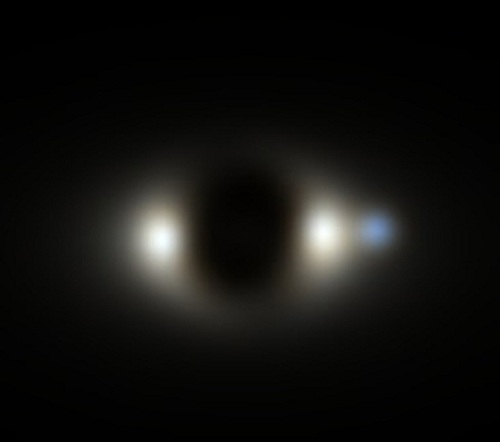

Image: A starshade would obscure the light of a star to allow its planets to become visible. Credit: Webster Cash/University of Colorado, Boulder.

The starshade would be placed 160,000 kilometers away from the JWST, which will orbit at the L2 Lagrangian point. And as Grunsfeld points out, that single dot yields other information:

…if you had enough time, and there were seasons, with ice covering and then going away, you could study it and be able to tell the difference between winter and summer on the planet, or vegetation, in principle. Just from unresolved single pixels, because of the color changes.

Given our inability to get a finalized Terrestrial Planet Finder design into the mix, the JWST thus becomes a major exoplanet asset, though a mission of daunting complexity, and one whose orbit would make any necessary on-site repair problematic, to say the least. Unlike Kepler, this is an instrument that can sample stars that are relatively near to the Earth. Most of the 150,000 stars in the Kepler field are further away, chosen because the goal of Kepler is to study a large number so as to achieve a statistical analysis of the incidence of the various kinds of planets around them.

Image: What a starshade might see, based on studies for a starshade concept called New Worlds Observer, one we’ve discussed many times on Centauri Dreams. The image shows an Earth-like planet at a distance of 30 light years. The white ring is dust in the stellar system, reflecting starlight under an angle of 30°. The central black disk is the shadow cast by the starshade. The Earth-like planet is the object with the familiar blue hue. Credit: Phil Oakley, Webster Cash (University of Colorado, Boulder).

Adding a starshade to the JWST mission profile adds to both cost and complexity, but the starshade would extend the telescope’s ability to see exoplanets. On its own, JWST can study a transiting world, but Mountain figures such transits might show up in no more than 5 to 7 percent of stars. The ability to take a planetary spectrum independent of the planet’s orientation around the star is what the starshade offers. We now wait to see whether JWST itself has a future. Its ballooning costs have threatened the project in Congress, but NASA administrator Charlie Bolden sees the telescope as one of the agency’s top priorities. With $3.5 billion already spent and ¾ of the construction and testing complete, Centauri Dreams thinks this mission will fly, but not without the kind of budgetary near-miss that is the nemesis of complex science everywhere. The loss of the Space Interferometry Mission will always be a reminder of what can still happen.

Why not just use asteroids in our own star system as a starshade?

The good news is that a star shade would be launched on a separate vehicle, after JWST is deployed and proven. The bad news is that JWST can not be serviced, and so will have a limited operational life (maybe 5 years?). It is most unlikely that the star shade could be approved, funded, designed, built, and deployed while JWST is still operational.

Hopefully the James Webb will be completed and launched. But with its checkered budgetary history, I’m doubtful about the money or will to “add-on” the starshade project. Regardless, it’s amazing to imagine we could have a handle on discovering and characterizing nearby earth analogues within the next decade! My two year old son could be learning about other earthlike worlds by the time he’s in high school. Astounding.

Those too busy looking to Wall Street for direction are already lost. The Stars Beckon!

I submitted to the NASA NIAC proposal office the idea that we should look into the feasibility of using a star shade in a high Molniya orbit and the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA) I suspect that the speed of the moving shadow and the aircraft would make observations difficult for planet hunting.

we would need two starshades one for each hemisphere

A post JWST World?

So much is going into the JWSTt that it is hard to think about space based telescopes beyond it. Certainly the JWST would yield even higher scientific value if both WFIRST ( infrared) and LSST ( NIR and vis) were completed and operational before JWST were launched. With a small field of view scope like the JWST choice of target is critical and these other two survey scopes would really help. HOWEVER, it looks as though JWST may fly alone. Given the time scales, it is important to think about the next generation BEYOND JWST now, so that after the five year mission is over there is a ‘scope ready to fly the next mission. I am not sure what that may look like but the sunshade Idea is promising, or perhaps twin or triplet telescopes of the 5 meter class, with expanded Field of View. The biggest improvements for the next scopes will come in the detectors, not the dishes. We need space based 10 gigapixel NIR and vis cameras and data transfer rates to get the info to earth! Even the GAIA space telescope is severely bandwidth limited. -and Santa Claus please bring us a 100 megapixel detector working in the 5 to 15 micron range!

QED: formation of Organic compounds in molecular clouds

Please note the recent publications and space.com article ( today) about the work of Dr Sun Kwok outlining the presence of very complex hydrocarbons in planetary nebula.

Complex organic compounds are very plentiful in the universe. This may mean that the would-be deep spacer traveler can pick a wide variety of destinations where expanding human technology can build a home. I favor icy bodies from 100 to 2000 Km in diameter as the eventual home for most of humanity, starting in our solar system and expanding across the cosmos. Human technology leading to interstellar plankton colonies with the size 1000’s to millions of humans, a rich exchange of culture, genetics and technology.

But that’s just my opinion.

With Space X rockets, a Bigalow refueling station in orbit, and a piloted Skylon outfitted to travel to L2, there will be no trouble at all servicing JWST. ‘Little Baby Steps’, isn’t that what the alien told her on the alien beach in the movie, ‘Contact’ . No need to cross your fingers and hope for Skylon, for the inflatable refueling station, or for JWST; the more perilous our Western civilization grows with all its finanancial misdeeds; a structural default likely by AD 2015; the more driving power will come to our quest for a new earth. And I don’t mean maybe.

Paul, The image you have above, just trying to get some perspective, what is the approximate resolution of the earth type planet?

The program/budgetary hurdles are still high for JWST. Assuming JWST does fly, I don’t think the starshade for JWST would be funded by congress through NASA. So maybe our partners in Europe or Japan could build and fly the shade and operate it in concert with us? Seems like this could be doable as a joint project.

Oh, as far a servicing JWST goes, perhaps SpaceX will be looking for further and farther opportunities for human spaceflight after 2015, assumnig they get “Dragonrider” qualified for operations. Contract them to transport a few telescope repair technicians out to L2 and back as needed. Seems like a good but achievable “stretch” goal for human spaceflight, and a good business opportunity for the commercial services providers.

I don’t understand the feasibility of using a star shade (because of the fact that it’ll be positioned 160,000 km from JWST). Not only would it have to be kept in perfect alignment between the target star and JWST, but to view a different star offset by 90 deg., you’d have to move the star shade something like 226,000 km to reposition it. Now, how is that feasible to view all the nearby stars (as I think is suggested in the Astrobiology article).

Scott: I think you would want to be more selective, and map out a path for the shade that would occult star systems known to have planetary configurations that provide good chances for interesting spectroscopy. If multiple shade craft were affordable, you could have JWST alternate between them as they achieve proper locations, along with all the other JWST observations, of course.

Scott, Mike :

JWST can and will observe other things while the shader is moving to the next target, no need to waste time in the meantime. It is not a exo-planet dedicated mission and it has plenty of other targets.

Mike, Enzo: Thanks, those are good points. Hopefully, by 2018 there will be new techniques available to digitally remove the glare of a star (making it’s planetary system visible) without the need for a star shade — as was recently done with archival Hubble data: http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/hubble/science/elusive-planets.html

Greg writes:

Sorry to be late on this! I don’t know the answer but the image comes from Webster Cash’s New Worlds Observer work, and I’ll see if I can get Cash’s comment on this. The figure may also be among the online docs:

http://newworlds.colorado.edu/docs/docindex.htm

Mike Lorrey writes:

Mike, the shape of the occulter is critical and a random asteroid surface won’t suffice. The various optical distortions that can occur depending on the shape of the occulter are only suppressed with a particular design developed for the job.

More for Greg on the resolution of the second image in the post. This just in from Webster Cash (U. of Colorado at Boulder):

“The second image is a simulation of the view with JWST. I believe that JWST

will have about 0.03 arcsecond resolution. So the blue spot is about 30

milli-arcsec in diameter.”

Characterising the Atmospheres of Transiting Planets with a Dedicated Space Telescope

Authors: M. Tessenyi, M. Ollivier, G. Tinetti, J.P. Beaulieu, V. Coudé du Foresto, T. Encrenaz, G. Micela, B. Swinyard, I. Ribas, A. Aylward, J. Tennyson, M.R. Swain, A. Sozzetti, G. Vasisht, P. Deroo

(Submitted on 6 Nov 2011)

Abstract: Exoplanetary science is among the fastest evolving fields of today’s astronomical research. Ground-based planet-hunting surveys alongside dedicated space missions (Kepler, CoRoT) are delivering an ever-increasing number of exoplanets, now numbering at ~690, with ESA’s GAIA mission planned to bring this number into the thousands.

The next logical step is the characterisation of these worlds: what is their nature? Why are they as they are? The use of the HST and Spitzer Space Telescope to probe the atmospheres of transiting hot, gaseous exoplanets has demonstrated that it is possible with current technology to address this ambitious goal. The measurements have also shown the difficulty of understanding the physics and chemistry of these environments when having to rely on a limited number of observations performed on a handful of objects.

To progress substantially in this field, a dedicated facility for exoplanet characterization with an optimised instrument design (detector performance, photometric stability, etc.), able to observe through time and over a broad spectral range a statistically significant number of planets, will be essential.

We analyse the performances of a 1.2/1.4m space telescope for exoplanet transit spectroscopy from the visible to the mid IR, and present the SNR ratio as function of integration time and stellar magnitude/spectral type for the acquisition of spectra of planetary atmospheres in a variety of scenarios: hot, warm, and temperate planets, orbiting stars ranging in spectral type from hot F to cool M dwarfs.

We include key examples of known planets (e.g. HD 189733b, Cancri 55 e) and simulations of plausible terrestrial and gaseous planets, with a variety of thermodynamical conditions.

We conclude that even most challenging targets, such as super-Earths in the habitable-zone of late-type stars, are within reach of a M-class, space-based spectroscopy mission.

Subjects: Instrumentation and Methods for Astrophysics (astro-ph.IM)

Cite as: arXiv:1111.1455v1 [astro-ph.IM]

Submission history

From: Marcell Tessenyi [view email]

[v1] Sun, 6 Nov 2011 22:22:16 GMT (386kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/1111.1455