A robust new computer model that couples the atmosphere of Titan to a methane reservoir on the surface goes a long way toward explaining not just how methane is transported on the distant moon, but also why the various anomalies of Titan’s weather operate the way they do. The model comes out of Caltech under the guidance of Tapio Schneider, working with, among others, outer system researcher extraordinaire Mike Brown. It gives us new insights into a place where the average surface temperature hovers around a chilly -185 degrees Celsius (-300 F).

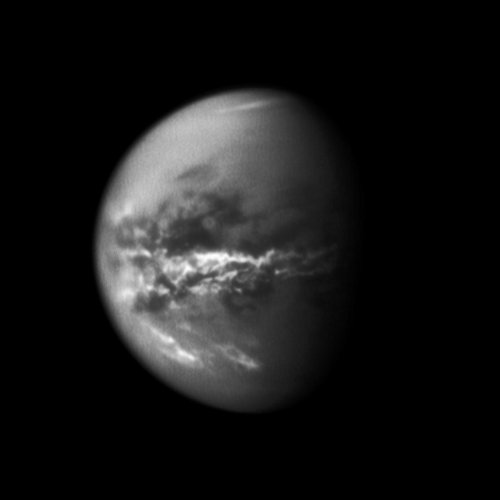

Image: NASA’s Cassini spacecraft chronicles the change of seasons as it captures clouds concentrated near the equator of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. (Credit: NASA/JPL/SSI).

Titan can a frustrating place for meteorologists to understand because during the course of a year some things happen that, in the early days of research, didn’t make a lot of sense. The moon’s equator, for example, is an area where little rain is supposed to fall, but when the Huygens probe arrived, it saw evidence of rain runoff in the terrain. Later, storms were found occurring in the area that did not fit then current models of circulation. The new three-dimensional model simulates Titan’s atmosphere for 135 of its years, which converts to 3000 Earth years. And it produces intense equatorial rains during Titan’s vernal and autumnal equinoxes.

According to the researchers, rain is indeed rare at low latitudes, but as Schneider says, “When it rains, it pours.” And the equatorial regions aren’t the only venue on Titan that the new model addresses. Titan’s methane lakes cluster around the poles, and it has been established by Cassini’s unceasing labors that more lakes exist in the northern than the southern hemisphere. According to Schneider, methane collects in lakes near the poles because sunlight is weak enough in those regions that little methane evaporates.

As to why more lakes are found in the northern hemisphere, let me quote from the Caltech press release on this work:

Saturn’s slightly elongated orbit means that Titan is farther from the sun when it’s summer in the northern hemisphere. Kepler’s second law says that a planet orbits more slowly the farther it is from the sun, which means that Titan spends more time at the far end of its elliptical orbit, when it’s summer in the north. As a result, the northern summer is longer than the southern summer. And since summer is the rainy season in Titan’s polar regions, the rainy season is longer in the north.

And there you have it — the summer rains in the southern hemisphere may be more intense because of stronger sunlight to trigger storms, but over the course of a year, more rain falls in the north, filling the lakes and accounting for their distribution. Older explanations that relied on methane-producing cryogenic volcanoes look to be in danger of being supplanted by the new model of atmospheric circulation on Titan, an explanation that requires nothing esoteric. The beauty of the work is that the model predicts what we should see in the near future: Rising lake levels in the north over the next 15 years, and clouds forming over the north pole in the next two.

Thus a set of testable predictions by which to evaluate the model emerge, what Schneider calls “a rare and beautiful opportunity in the planetary sciences,” and one which should help us refine the model as events progress. “In a few years,” he adds, “we’ll know how right or wrong they are.” Adding to its weight is the fact that the model reproduces the observed distribution of clouds on Titan, which earlier atmospheric circulation models had failed to do. The paper is Schneider et al., “Polar methane accumulation and rainstorms on Titan from simulations of the methane cycle,” Nature 481 (5 January 2012), 58-61 (abstract).

Truly excellent work, concerning the only other body in the Sol system with a solid surface, a nitrogen dominated atmosphere, and open bodies of liquids. There is much to be learned here. I understand the astrobiology obsession with liquid water, but deep drilling landers for Europa or Enceladus are far over the planning horizon. I would choose a purpose built Titan mission as the next outer moons probe in a heartbeat.

Relative to other known atmospheres , titan has very litle oxygen . Is this only on the surface , could there be large amounts of oxygen locked up underground , perhabs as a deeper layer of water ice ?

Titan is an awesome beautiful world. I wonder how the dunes form there from the wind patterns. How strong would any winds be? And could the winds cause waves? How high the waves? Also I wonder if there are any active volcanoes or quakes. We should send a methane fueled robot.

If our society had its priorities straight, we would be sending an armada of probes to Titan – among other dedicated space missions.

No ljk, its not about priorities its about our need to wonder. If we could just communicate to the general public our own esoteric knowledge of Titan’s beauty as noted by Tarman, and convince them of the futility of just following the water to find life, as noted by Joy, then they would demand further investigation. Just trust me; that is all we must do.

True, Rob, except that which is liquid and flows on Titan is not water. :^)

Cassini’s radar observes Titan’s tropical dune fields

23 Jan 2012

Sand dunes are common on Earth, Mars, Venus and – unexpectedly – on Saturn’s giant moon, Titan. Now detailed analysis of radar observations gathered during the Cassini spacecraft’s flybys of cloud-shrouded Titan is enabling scientists to understand the distribution, shape and dimension of its exotic dunes.

Most people are familiar with the piles of loose, granular material which make up sand dunes in coastal areas and deserts on Earth. Derived from the weathering and erosion of rocks over many millennia, these wind-blown, shifting dunes are capable of transporting huge amounts of material.

While Titan’s dunes resemble in many ways the features found on Earth, they are made of tiny particles of organic (carbon-rich) material which have fallen to the surface as a never-ending “drizzle” from the dense, orange clouds above. As such, they are the largest known reservoir of organics on Titan, playing a key role in the moon’s carbon and methane cycles.

Full article here:

http://sci.esa.int/science-e/www/object/index.cfm?fobjectid=49878