Andreas Tziolas, current leader of Project Icarus, gave a lengthy interview recently to The Atlantic‘s Ross Andersen, who writes about starship design in Project Icarus: Laying the Plans for Interstellar Travel. Icarus encounters continuing controversy over its name, despite the fact that the Icarus team has gone to some lengths to explain the choice. Tziolas notes the nod to Project Daedalus leader Alan Bond, who once referred to “the sons of Daedalus, perhaps an Icarus, that will have to come through and make this a much more feasible design.”

I like that sense of continuity — after all, Icarus is the follow-on to the British Interplanetary Society’s Project Daedalus of the 1970s, the first serious attempt to engineer a starship. I also appreciate the Icarus’ team’s imaginative re-casting of the Icarus myth, which imagines a chastened Icarus washed up on a desert island planning to forge wings out of new materials so he can make the attempt again. But what I always fall back on is this quote from Sir Arthur Eddington which, since I haven’t run it for two years, seems ready for a repeat appearance:

In ancient days two aviators procured to themselves wings. Daedalus flew safely through the middle air and was duly honoured on his landing. Icarus soared upwards to the sun till the wax melted which bound his wings and his flight ended in fiasco. The classical authorities tell us, of course, that he was only “doing a stunt”; but I prefer to think of him as the man who brought to light a serious constructional defect in the flying-machines of his day. So, too, in science. Cautious Daedalus will apply his theories where he feels confident they will safely go; but by his excess of caution their hidden weaknesses remain undiscovered. Icarus will strain his theories to the breaking-point till the weak joints gape. For the mere adventure? Perhaps partly, this is human nature. But if he is destined not yet to reach the sun and solve finally the riddle of its construction, we may at least hope to learn from his journey some hints to build a better machine.

I love the bit about straining theories to the breaking point, and also ‘hints to build a better machine.’ Anyway, those unfamiliar with the Icarus project can use the search engine here to find a surfeit of prior articles, or check the Icarus Interstellar site for still more. You’ll also get the basics from the Andersen interview, which goes into numerous issues, not least of which is propulsion. Tziolas notes that Project Icarus has focused on fusion, although ‘the flavor of fusion is still up for debate.’ Seen as an extension of the Daedalus design, fusion is a natural choice here, because what Icarus is attempting to do is to re-examine what Daedalus did in light of more modern developments. But the He3 demanded by Daedalus is a problem because it would involve a vast operation to harvest the He3 from a gas giant’s atmosphere.

Image: Icarus project leader Andreas Tziolas. Credit: Icarus Interstellar.

As the team studies fusion alternatives, other options persist. Beamed propulsion strikes me as a solid contender if you’re in the business of starship design in a world where sustained fusion has yet to be demonstrated in the laboratory, much less in the tremendously demanding environment of a spacecraft. We’ve already had solar sails deployed, the Japanese IKAROS being the pathfinder, and laboratory work has likewise demonstrated that beamed propulsion via microwave or laser can drive a sail. But beam divergence is a problem, which is why Robert Forward envisioned giant lenses in the outer system demanding a robust space manufacturing capability. So the dismaying truth is that at present, both the fusion and beamed sail options look to be not only beyond our engineering, but well beyond the wildest dreams of our budgets.

Where we are clearly making the most progress in interstellar terms is in the choice of a destination. Obviously, we lack a current target, but within the next two decades it is well within our capabilities to launch the kind of ‘planet-finder’ spacecraft that can not only home in on an Earth analogue around another star but also study its atmosphere. It would be all to the good if we found that blue and green world we’re hoping for orbiting a nearby system like Centauri B, but we’re going to be learning very soon (depending on what gets budgeted for and when) which nearby stars have planets that might be suitable targets. Icarus is not just looking for any old rock — the goal is to design a craft that could reach a world that could be habitable for humans.

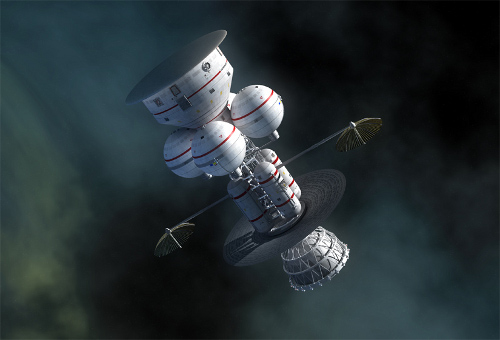

Image: One vision of the Icarus craft, by the superb space artist Adrian Mann.

Why that criterion? Survival of the species is a serious interstellar motivation. Tziolas asks whether, if humanity becomes capable of going to the stars and chooses not to, it wouldn’t deserve a Darwin Award, the kind of achievement that marks its recipient as doomed. But motivations cover a wide range. I’ve written about the human urge to explore on many occasions, and Tziolas talks about pushing back technological boundaries as another prime driver. Hard problems, in other words, drive us to push the envelope in terms of solutions:

In order to achieve interstellar flight, you would have to develop very clean and renewable energy technologies, because for the crew, the ecosystem that you launch with is the ecosystem you’re going to have for at least a hundred years. With our current projections, we can’t get this kind of journey under a hundred years. So in developing the technologies that enable interstellar flight, you could serendipitously develop the technologies that could help clean up the earth, and power it with cheap energy. If you look toward the year 2100, and assume that the 100 Year Starship Study has been prolific, and that Project Icarus has been prolific, at a minimum we’d have break-even fusion, which would give us abundant clean energy for millennia. No more fossil fuels.

And let’s not forget ongoing miniaturization, also a prime player in any starship technology:

We’d also have developed nanotechnology to the point where any type of technology that you have right now, anything technology-based, will be able to function the same way it does now, but it won’t have any kind of footprint, it will only be a square centimeter in size. Some people have characterized that as “nano-magic,” because everything around you will appear magical. You wouldn’t be able to see the structures doing it, but there would be light coming out of the walls, screens that are suspended that you can move around any surface, sensors everywhere — everything would be extremely efficient.

This is a lively and informative interview, one that circles back to the need to drive a shift in cultural attitudes as a necessary part of any long-haul effort. Some of this is simply practical — the creative souls who volunteered their engineering and scientific skills on Daedalus are retiring and some have already passed away. A new design requires a new generation of interstellar engineers, one recruited from that subset of the population that continues to take the long view of history, acknowledging that without the early and incremental steps, a great result cannot occur.

To name the 100 year study after a metaphor on what happens to the ill-prepared and brash, is very, er, Freudian. (and Freud was a quack).

I’m partial to The Robert A. Heinlein Centennial star ship, “High Frontier”. Or, simply “The Heinlein”. That, or Enterprise.

Either would do in a pinch.

Even more than any issue of the name of the starship concept, which I have to admit it is impressive to see how the team is bending itself into a pretzel to make the name Icarus work, including the idea that the concept will be pushed to the breaking point, I have a real issue with the motto, “Flying Closer to Another Star”, which can be seen right on their logo here:

http://www.icarusinterstellar.org/images/img_01.gif

Since the plan for Icarus is to actually stop the vessel in the target star system and presumably circle the alien star and drop some probes down on any non-self-luminous bodies there, saying that Icarus is going to get near a star does not sound terribly bold or enthralling.

JFK said in 1961 that America was going to put “a man on the Moon and return him safely to Earth” by 1970, not that NASA might get a guy near Earth’s satellite and bring him right back before he gets hurt. If one isn’t going to go all out for a goal or have confidence that it can be done, then don’t say or do anything at all. This is so especially true for a mission to another star system, particularly if you want to engage and motivate the public that you will need to support you on such a major endeavor.

So, how about “To Alpha Centauri or Bust!” Or “All the Galaxy or Nothing!”

Granted, the latter sounds like humanity wants to conquer the Milky Way, but hey, for those who think nothing living exists beyond Earth, this should not be a problem. It also does not seem to be a problem for those who get really excited about the idea of other Earths out there and think we will be sending a colonization effort to them – while seeming not to realize or ignore the strong possibility that any world similar to our planet means it may also have its own native life forms, who may not be compatible with or like the fact if they are smart enough that some very foreign beings have decided to move in permanently.

As for the plans to make Icarus a fusion-driven system, I hope that the Icarus team will be ready to sell the point that if they can develop an actual working fusion engine, this will translate into the reality of a very clean and powerful nuclear energy source for all of human civilization. This is probably one very big reason that DARPA is so interested in the idea of a starship in the first place. The potential financial windfall from this development could pay for a dozen Icaruses or more.

The other benefit will be the quelling of those who constantly whine about money being spent on space when it should be used to solve every problem of humanity first, despite the should be obvious fact that so much more money has already been spent on human issues than space and we still have plenty of problems on Earth.

Next up: My thoughts on putting an information package on Icarus for the rest of the galaxy.

To quote from The Atlantic interview article pasted below after my comments, it is nice to see that the Icarus team is seriously considering the idea of an information package on the probe, since we will be sending it off into unknown realms and someone who finds it might like to have an idea what a giant alien vessel is doing in their celestial backyard and who sent it.

My comments on Tziolas’s comment about the design of this particular form of METI: The Golden Record of the Voyager probes has the advantage of being both simple and robust. You do not need a lot of fancy equipment to operate it to get the data. Indeed, the probe makers included a needle and stylus so that if the finders can do nothing else, they could put the needle in the record groove and at least listen to the music, sounds, and human greetings (yes, yes, assuming the finders have ears or their equivalents).

In summation, keep things relatively simple as possible and do not assume that just because the finders will have to have some kind of interstellar travel capability automatically means they can figure out anything built by humanity. We will be dealing with an alien mindset here, perhaps including those of our descendants.

As for Tziolas’s idea about having some way to alert others to the existence of Icarus and its messages, while I understand wanting to make sure that the probe and its greetings to the galaxy from humanity have a chance to get noticed, the problem I see with his plan for this attention-getter is that it may not last long enough to get the job done, as I am going to assume the alien civilization he is referring to is one that is unknown to us and therefore would require a Benford-style beacon in order to succeed.

The plan also has the drawbacks of keeping the whole concept of an information package relatively simple and may even be perceived as taking away from vital resources for the primary operation of the interstellar probe. The Pioneer Plaques and Voyager Records were included primarily because they did not take up a lot of room or weight aboard those probes and did not interfere with the main operations of the robot vessels and their primary mission goals.

The NASA folks who worked on Pioneer 10 and 11 and Voyager 1 and 2 were not terribly interested (at least not publicly) about where these probes were going to end up in deep space after their planetary flybys. This is why New Horizons on its way to Pluto has nothing like the plaques or records, because the mission team was not interested in investing time to send the equivalent of a calling card into the galaxy. That is what happens when one is the member of a species that only lives about 80 years on average and has been civilized for only a few thousand years in a galaxy and Universe that is billions of years old: They have trouble seeing the very long and wide picture.

So the point is, let us make sure that when Icarus or its equivalent happens, it will be carrying information and messages from humanity of substance because the package meshed itself with the mission rather than never making the flight because those who were on the design team got carried away.

Maybe what we need are some probes whose job it is to act as beacons to let the galaxy know that humanity exists, assuming we are truly ready for a response from a real alien intelligence. Of course this probably will not happen before we get those initial exploration missions out there first.

For those who worry about this particular form of METI as described by Tziolas, perhaps we should not send anything out there at all if we don’t want to be detected by an alien species. In that case, then, we should do nothing at all, which usually leads to stagnation and extinction. I often note that those who worry about METI focus on the electromagnetic transmissions and not the physical probes are already wending their way into the wider Milky Way.

A probe may be much smaller and slower than a radio signal, but I can also see issues with the presence of a spacecraft that comes into the realm of an ETI unknown and unannounced. Thus the need for a readable information package about us and the original purpose of the human interstellar mission.

Plus they would make for excellent records for our descendants, preserving human history for ages beyond what could survive on Earth.

The quote from The Atlantic:

Have you and your colleagues given any thought to including something like the Golden Record that was stowed away on the two Voyager probes, the disc of sounds and images from Earth compiled by Carl Sagan?

Tziolas: We have, actually. It only took a week after the project began for people to start putting together a new record, and to start thinking about what the content of the record would be, but we haven’t really agreed on what the message would be. After the core design team had the initial discussion, we decided that the message should not be designed by physicists and engineers but rather by a sociologist or an anthropologist, but that was the limit to what we agreed on.

We all agreed that what Carl Sagan sent was great; we just need to adapt it to our own time. Since then we’ve been actively trying to recruit anthropologists and sociologists to the team.

One of my concerns is that if we send another golden disc, it might not be well suited to reaching its audience. The chances of an extraterrestrial finding it and reading it are worse than a needle in a haystack; it’s like a particle in a universe.

So my preference is to design some kind of module that was more technological than the analog disc, that way you could send it in to orbit around your target star, equip it with solar panels, have it charge up and once every twelve hours or so it gives out a pulse. And that would be just to give this other civilization something to look at, and when they design the capabilities to go check it out, they would, and then inside there would be something static, something like the golden record.

Icarus is actually the perfect name. The name denotes a very humble attitude toward trying to accomplish the greatest achievement in human history for which we are not yet able to accomplish just as Icarus was unable to fly so close to the Sun.

I wanted to see if Daedalus had any other children or relatives or some associates who would work in terms of naming a spacecraft following the BIS lead. I came across the following information:

Daedalus had a nephew named Perdix (though some other ancient sources called him Talos or Calos) who was a very clever inventor. He was so clever that Daedalus became jealous enough of Perdix to shove him off a cliff! The goddess Athena intervened as Perdix was plunging to his death and turned the young man into a bird, who flew away to safety.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perdix_(mythology)

In light of this, perhaps we should try naming star vessels after real people who made important contributions to interstellar travel and exploration.

The only Icarus-like aspect of this idea is imagining that any Earthly civilization would ever throw away 5oo TeraWatt years of fusion heat (centuries of world supply) on any celestial endeavor whatsoever, rather than harness it as the follow-up to Peak Oil and Peak Coal. It’s also rather Icarus-like to imagine that such a fusion apparatus could ever run unattended, let alone after a century of radiation exposure.

Only an interplanetary civilization of rich mega-habitats, by the thousands if not millions, would ever think of using so much fuel in a single mission, and then only as the culmination of a long period of capacity-growth in fusion technology, particularly for outer-planet missions.

As for how much development remains on the two main alternatives, the laser sail today is a century ahead of fusion. Solar-pumped lasers already exist, while fusion remains the same pipe dream of the fifties: still a half-century away.

Let’s face it — it’s easy to imagine giant solar optics pumping an asteroid-sized gas-laser with equally giant collimation optics with 10-ly range. It’s easy to imagine the first manned mission to a star system building such a device as a reciving laser. The Icarus fusion lasers — not so much.

Finally, tt’s also easy to imagine fleets of hyper-telescopes that could find habitable planets a million times more cheaply than any interstellar probe, so can we stop bringing up these silly notions that unmanned probes will ever find habitable worlds? Anyway, the nearest EarthWorld is probably 10,000 ly at least. From Earth’s geohistory it’s plain that high-oxygen worlds will be found to be extremely rare.

Project Icarus: Mechanisms of the Interstellar Machine

Guest contributor Philipp Reiss compares the Icarus starship with Columbus’ Santa Maria, exploring the similar mechanisms used on two ships of different ages.

Mon Feb 27, 2012 01:11 PM ET

Content provided by Philipp Reiss, Project Leader for the Icarus “Mechanisms” module.

Full article here:

http://news.discovery.com/space/project-icarus-interstellar-starship-mechanisms-120227.html?fb_ref=fb2&fb_source=home_multiline

“As for the plans to make Icarus a fusion-driven system, I hope that the Icarus team will be ready to sell the point that if they can develop an actual working fusion engine, this will translate into the reality of a very clean and powerful nuclear energy source for all of human civilization. This is probably one very big reason that DARPA is so interested in the idea of a starship in the first place. The potential financial windfall from this development could pay for a dozen Icaruses or more.” – ljk

Aye, there’s the rub. The G20 has just put together a plan to use $2 trillion of imaginary currency to keep the financial system afloat for a few weeks or months longer. To Infinity and Beyond! Exponential creation of currency units in cyberspace is easy.

However, assembling the actual human and material resources of China, the European Union, India, Japan, Korea, Russia and the United States to build the rather modest ITER experiment has been an epic struggle. The start of Deuterium-Tritium operation is now planned for March 2027. Fifteen years from now! There is nothing in the history of fusion research to suggest that the project will even be able to meet this relaxed schedule. Furthermore, fusion rocket drives, as Daedalus noted, favour the much more difficult to ignite D-He3 reaction – using a fuel not available on Earth. But we will put that niggling problem aside for the moment.

It is hard to see what the Icarus project could add to the disappointing fusion efforts at ITER, NIF, and the Z pinch facility at Sandia. Imagine I am a trillionaire (they do exist). What sales pitch would I hear from the Icarus team regarding fusion? What do they know that everyone else has overlooked in the past 56 years? Does Icarus have a physicist smarter than Andrei Sakharov?

@LJK: I think the probability of any of our dead, discarded craft coming anywhere close enough to another star to have a chance of being detected is minuscule even in billions of years. So, while I think it is a nice idea to put a record or a picture, it cannot ever be more than a slightly quaint gesture good mostly for stroking our own egos.

@Bill, I suppose different people find different things easy to imagine, but I think the role of telescopes in finding planets and probes in investigating them should be clear enough for anyone to agree on. Contrary to what you seem to be saying, the better our telescopes get, the more we will want to send eyes, ears, drills, claws, gas analyzers, spectrometers, and all the rest there to get a closer look.

Paul, thank you for covering the story here. It was very fun to do and was pleased to see Ross Andersen carrying the interview over almost intact.

The discussion in the comments here and there, over the name of the project really is secondary to the endeavor. Having put together such a wonderful team of people (almost doubling in size every year) willing to contribute their time to understand the problem of interstellar flight and perhaps, in some small way, facilitate its realization in the future is its own reward.

As for the bit about METI discussed by ijk in detail above, I should say that this was my personal view, add some creative license for the purposes of responding to the interview question, as was the alt-myth justifying the name.

I liked the description of how we’re bending ourselves into a pretzel to make the name work. We do in fact wear the name with pride.

As for the tagline “Flying Closer to Another Star” – this is what Icarus Interstellar is dedicated to achieving. I can only hope that at 37 I have enough time to see Icarus mature to the point where we are flying interstellar precursors and one of our babies holds the Guinness book of records for the closest human-made object to on route to Alpha Centauri.

PS: From the ITER project website:

“The incredibly complex ITER Tokamak will be nearly 30 metres tall, and weigh 23,000 tons. The ITER Tokamak is made up of an estimated one million parts.”

But that’s not all, the 23,000 tons is just the Tokamak! No generators or cooling system included.

“The most important feature of the ITER site today is the completed 42-hectare platform—the approximate size of 60 soccer fields—that will hold the scientific buildings and facilities.”

Ok, I will allow that if anyone ever perfected a fusion reactor design that the R&D facilities would not be needed. So maybe a production version would be automated. Of course you would need at least two tokamaks so one could be shut down for maintenance, “materials that can withstand 60 years of exposure to radiation from fusion operations simply don’t exist”. Add in the generators and radiators and I figure that a tokamak fusion power plant (For a colony on Titan? Or for a generation ship?) would mass about 100,000 tons. This is not a blueprint for fast flight hardware.

But what about inertial confinement and the NIF facility at LLNL? The one with the laser system requiring a ten-storey building the size of a football field. So far it has been operating at just 2 shots a day, while a power plant or spaceship propulsion operation would require circa a million shots a day, and they are still struggling with issues regarding damage to the optical components. Obviously this butterball turkey will never fly.

There is a plan to try to use newer (untested at extreme power levels) laser technology to build something sized more like a D-T version of the old Daedalus power plant idea by 2030. The Laser Ignition Fusion Energy (LIFE) concept, a compact, modular version of the NIF laser system might fit in a 10 meter-long unit. The main difference between NIF and the LIFE designs for energy production will be the adoption of laser diodes to pump the Nd:glass amplifier crystals, meaning that the entire system will become a lot more energy-efficient and – it is hoped – suitable for commercial deployment. How realistic is this? Well, NIF was completed five years behind schedule and was almost four times more expensive than budgeted … Only now is Mike Dunne, the National Ignition Facility’s director for laser fusion energy, is expecting the giant laser system to generate fusion with energy gain, or “burn”, by the end of 2012. Could LIFE be a reality by 2030, 2035, ever?

Andreas Tziolas and the Icarus crew should do a site visit to ITER and have a long chat with Mike Dunne’s team before investing too much of their energy on fusion designs.

While I wouldn’t accept Joy’s position that if the large government projects can’t do fusion, a small group is, almost a priori, not going to offer anything new, it is a valid point that should be explained by the Icarus team. There are small private groups working on fusion, but despite occasional PR and funding hype, never produce anything. As far as the early 1980’s, teh defunct Omni magazine was seed funding Robert Bussard [?] and his disposable “light bulb” fusion design. Obviously that was a bust.

While I support better telescopes and ultra miniaturized, beamed probes for nearby star investigation, it is clear that the appeal of a Daedalus/Icarus design is that it could scale for human flight. The energy requirements are just huge and one has to wonder if our ideas of transporting humans as meat across the stars will seem as quaint in one hundred years as an idea that rapid global communications would human messengers to be shuttled about by some contraption.

Given the 100 year horizon, I would guess that we will either find some new physics that will allow star flight, or that slow flight will be needed for receivers of information for local assembly of machines, or possibly that humans will be able to create electronic copies of their minds for starfaring via this beamed approach. A fusion powered starship will look as improbable as a steam powered aircraft at the end of the C19th.

What I would hope for is that the Icarus group spins off novel ideas that have not been explored by the SF authors before them, and given some real flesh that could have wide applications on earth and in space.

I’m really pleased with this article. It touches upon many of what I think are the major issues facing us as we seek an actual first true interstellar mission.

> Beamed propulsion strikes me as a solid contender if you’re in the business of starship design

It may well be that beamed propulsion is a more feasible option than fusion for the first true interstellar mission. I don’t believe that our community nor Icarus Interstellar specifically has openly and fairly competed the propulsion options against each other even with our current level of understanding. I think that we should.

The possibility that a propulsion method other than fusion is more feasible initially has important implications which affects us now. For example, in Hailey Bright’s interview of Jim French, he was indicating that he would be approaching potential donors with a vision of fusion-based interstellar travel. But if beamed propulsion turns out to be more feasible, then why start heading down a less relevant path? Concepts need to be competed against each other in an evidence-based manner first.

> Icarus is not just looking for any old rock — the goal is to design a craft that could reach a world that could be habitable for humans.

Think about it. Our Moon is inhabitable for humans. The younger generation will probably colonize it in their lifetimes. So we need to be open minded about what habitable for humans means.

If Project Icarus comes to a complete stop for scientific reasons… how tempting it would be to see if the mission to this man-inhabitable world could go the next step and deliver people. It would depend upon how reliable our long-term life support was at time of launch or how advanced biomedical, robotic, and intelligent expert systems. These are information-based fields which are accelerating and so could be mature by the time a large space infrastructure (for fusion our beamed propulsion) exists. But a “manned” mission would fundamentally change not just the design but even the rationale for a Project Icarus or a beamed mission.

> Tziolas asks whether, if humanity becomes capable of going to the stars and chooses not to, it wouldn’t deserve a Darwin Award, the kind of achievement that marks its recipient as doomed.

Yes but no. Yes, there is a very real issue about the survival of the species that should inform (I’d argue drive) our interstellar plans. But the issue is not so much our choosing never to leave the solar system but rather being exterminated by or own technology prior to our having the capability to leave the solar system – something far more likely. We need to determine the absolutely earliest way we can send humans to another star system.

Miniaturization is probably key. Much lower mass = much lower energy = lower in-space infrastructure = lower cost = earlier launch. Our first true interstellar mission should be “manned” and launched at the earliest possible date.

One more thing. About the Project Icarus name. It’s good. We should keep it. But I think that Icarus Interstellar is problematic. Icarus Interstellar is for all things interstellar. But it would be too easy to confuse the two and conclude that the purpose of Icarus Interstellar is to develop Project Icarus. It’s much broader than that. I would prefer something like the International Interstellar Society or something of the sort.

Travelling to other star systems is a century or two farther into the future than we dream. The economies of this single planet are not big enough for the scale (mega or nano) of the job and the high tech competance required. But we are competant enough to burst into and claim ‘our’ Solar System. In a couple more centuries our economy will expand organically to use Luna, Mercury and Mars and countless Asteroid Belt mines, and even the resources of Jovian System. Jove will be our first new ‘system’.

You gotta walk before you can run. Luna is coming up very soon to agenda of the great powers, and the industrialists.

Eniac

I only said that unmanned probes weren’t going to DISCOVER habitable planets, because they’re too rare and distant. I never said it wouldn’t be valuable to have a probe in another star system, just that it will never be done by an Earthbound civilization. The mass-deltaVee product for an interstellar mission to even the closest stars is fantastically higher than that of even the most gradiose hypertelescope fleet, so much so that no probe will ever be sent to a star just to see what’s there. Knowing what’s there will be the reason the probe is sent, not vice versa.

Joy

I too have my doubts about ITER and in fact think that the money spent there will actually INHIBIT development of fusion ( See! they spend 50 billion on this and it STILL does not work!) .

However all hope is not lost. the Z pinch machines can and have easily achieve temperatures FAR in excess of what is needed for most interesting forms of fusion ( D-T, He3 -D, D- D, B-P and any lithium schemes) . The big concern right now is with the possibility of making thermonuclear devices that do not require fission and can fit into a car, ( the technology can be compact) . It is not commercial and interestingly the whole discussion of Z- pinch technology has goon curiously Dark, after some real excitement earlier in the decade. While absence of evidence proves nothing, it may be expected that a nuclear technology with possibilities of weaponization would not be advertised. Sandia is still doing experiments and occasionally things ( results) bubble up to the surface, they are building more powerful versions of the machine, ( at a fraction of the cost of ITER. ). It is still left to publish real fusion results and the density / size of the plasma is an issue- it is a problem if the fusion mass is so high the energy generated destroys the chamber. There are still issues with plasma stability but really it is looking pretty great. if we built 5 of these instruments and explore a lot of physics with them we might make this work very well. -Still need to convert the heat /radiation back into electricity ( or propulsion) . By the way, production of tritium is just a pain but is not particularly difficult, and it decays with a 11 year half life to He3, which is then stable. It is cheaper to make it here than mine it elsewhere.

in a Z machine it may be possible to do directly to D-D and there is a nearly unlimited supply of that.

Andreas Tziolas said on February 28, 2012 at 5:05:

“As for the bit about METI discussed by ijk in detail above, I should say that this was my personal view, add some creative license for the purposes of responding to the interview question, as was the alt-myth justifying the name.”

LJK replies:

Andreas, I had the feeling that it was kind of an off-the-cuff, first-run idea, which is both fine and understandable, especially since you were being interviewed. Even if the technical details will be different in the long run, you bring up some good points about how we should represent ourselves on our first serious interstellar ventures and how we need to make them noticeable should our intention be to make some form of contact with an ETI.

Andreas then said:

“I liked the description of how we’re bending ourselves into a pretzel to make the name work. We do in fact wear the name with pride.”

LJK replies:

You should take it as a compliment to a degree, as I am impressed with the lengths taken to continue with the Daedalus legacy, which is understandable. However, I am still of two minds on naming our first potential star probe after a mythological figure who literally crashed and burned, no matter how much the underlying meaning is supposed to keep us aware and humble of the effort to traverse interstellar space.

Andreas then said:

“As for the tagline “Flying Closer to Another Star” – this is what Icarus Interstellar is dedicated to achieving. I can only hope that at 37 I have enough time to see Icarus mature to the point where we are flying interstellar precursors and one of our babies holds the Guinness book of records for the closest human-made object to on route to Alpha Centauri.”

LJK replies:

In the interest of promoting Icarus to the general public and those who will ultimately foot the bill for this project (they likely will not be scientists, unless they are very, very rich scientists – and how many of them exist?), you need not and should not be so accurate to a fault when it comes to your mission motto.

Yes, we readers of Centauri Dreams and such like-minded folk know you are not going to actually land Icarus on an actual star, but to the average Joe and Jane, if you are not going to actually step onto the very tip of Mount Everest and say so as your goal, implying that you are going to set up camp somewhere in the vicinity of the mountain top is not going to cut it. To sell Icarus, you need to say Alpha Centauri of Bust! and I am not wavering on that issue, even though it is quite clear that minds have been made up.

This is why scientists and engineers need PR folk sometimes. The LHC is a prime example of this. A while back a project scientist was being interviewed by a reporter, who asked him about the probabilities of the LHC creating a black hole that would swallow up Earth. The scientist, behaving as he was trained, told the reporter the chances were incredibly small of such an event happening. Accurate in terms of probability, but the reporter interpreted this as there was a chance that the LHC could destroy the planet just the same! And thus all the subsequent nonsense about black holes and aliens popping out at CERN and dooming us all, rather than the public focusing on what the biggest particle collider in the world could do for human knowledge.

We must not forget the high profile of the name Icrus, and how very many know the legend. I googled Daedalus and got a million hits, but Icarus got 29 million.

If we want to build a reasonably fast probe inside the next 30 years , fission is the way to go . Fusion as well as beamed power is stil much longer into the future , and propulsion is far from the only important issue waiting for solutions . A near tirm fission powered probe might serve many diferent purposes even if it might never reach another star . It could be “creewed” by an artificial closed ecologic system such as the one used by Larry Niven in “The legacy of Heorot” , it could send back vital information about how the spectrum of earthshine changes with distance , And it could be a platform for learning about longterm maitenance using robots . Many of these longterm problems would have to be learned first inthe laboratory , and this is perhabs the one important thing the ISS could be used for . If we define it as a goal to maintain the ISS indefinetely , it will be a shortcut to encountering and solving more and more hard maintenance problems . Also an early version of the fissionmotor could boost the ISS to a longterm stable orbit .

@Bill, Sorry, I appear to have misunderstood you. It would indeed be ludicrous to argue that probes will find or discover new worlds, and I have not heard anyone do so. They will, however, be sent there to explore those worlds in the many ways that telescopes can’t, no matter how large and expensive.

Like Ole, I am of the opinion that fission should be a prime contender. In terms of theoretical optimal Isp, fusion is barely better than fission (2-fold at best, much less if we have to let those pesky neutrons go unused). We know how to do fission, even though we do not yet know how to use it for propulsion, efficiently. One out of two ain’t bad, however – with fusion we can do neither.

Eniac said on February 27, 2012 at 23:33:

“@LJK: I think the probability of any of our dead, discarded craft coming anywhere close enough to another star to have a chance of being detected is minuscule even in billions of years. So, while I think it is a nice idea to put a record or a picture, it cannot ever be more than a slightly quaint gesture good mostly for stroking our own egos.”

LJK replies:

Yes, the odds are slim for probes sent drifting into interstellar space, but in the case of vessels like Icarus, which are supposed to stay in the target solar system, the odds increase tremendously at the very least for future human explorers or their descendants. And, hey, if someone out there is going in person or by robotic proxy to all 400 billion star systems in the Milky Way as you claim, there you go!

Having an information package on our deep space vessels not only won’t hurt anything or cost much, it will be a major investment should an ETI ever actually find them one day. And if you want to get even more practical, putting information about humanity in space will preserve such knowledge far longer than anything will last on Earth, for many millions to perhaps even several billion years in time.

As for ego stroking, the human race should be proud of doing something good and expanding our tiny horizons.

Interstellar Bill, you bring up some good and concerning points about using a fusion engine to power Icarus. My assumption is that if the Icarus team or some other group ever does develop a working fusion power system, it will be a “spinoff” from a setup for powering our civilization first and not something isolated for Icarus alone.

Several times in this very blog I have suggested that Icarus should pursue the Orion propulsion concept instead of fusion, for which we have the technology and the largest possibility of making it work. I was told to go start my own starship group, and I mean that literally. I also brought up the possibility that China could have the Orion vessel first, as they have sophisticated space and nuclear programs in addition to vast tracts of barren wasteland to test Orion in and the resources, human power, will, and drive to make it happen. They also seem to lack to fear of nuclear power so often found in the West. I was told I was being xenophobic.

Without a real propulsion system, Icarus will be little better than the starship Enterprise. I too can propose an antimatter or ion driven interstellar probe, but without the real technology behind it, what good will it do? This is why I am saying let us focus on technologies we do have NOW if you ever want to see Alpha Centauri up close. Otherwise I might as well just keep on reading science fiction.

Rob Henry said on February 28, 2012 at 18:25:

“We must not forget the high profile of the name Icrus, and how very many know the legend. I googled Daedalus and got a million hits, but Icarus got 29 million.”

Entering Adolph Hitler in Google gets one 31,300,000 hits, but no one would want to name anything after him.

@LJK:

You are right. I forgot that Icarus would be parked in the target system. If put in a distinctive orbit around a distinctive body, it would very likely be found by future visitors or inhabitants of that system. Even a sufficiently close stellar orbit would probably work. Of course, most likely those inhabitants would be our descendants and already know everything about us, but you never know…

The problem I see with these designs is that they are dramatically under-estimating, or just ignoring, the difficulty of keeping machines and/or biological self-contained systems viable in space.

The vaccum, cold, and radiation levels of deep space are universally destructive to complex machinery. Gases and fluids diffuse out of the system, plastics and metals become embrittled or vacuum welded, radiation and dust impact etches away at materials.

Hundreds of years travel duration? Nonsense. We can barely keep spaceships alive for a few decades before they fall apart. We can make them self-repairing but such a self-repairing system will be exponentionally larger, and that exponential factor will get larger the farther we propose to travel. (Law of Ecosystems…the size of the self-contained ecosystem increases with the square of the time it must remain self-contained).

So in summary, the interstellar travel movement will need to start looking much more closely at their assumptions of the size and weight of these systems. As a minumum, you should take all your weight estimates, for every type of craft, and multiply by a factor of 10.

In the end, it is likely that Fermi’s Paradox can be easily explained. The reason other intelligent species haven’t already colonized the galaxy is…it can’t be done by any race, with any technoloy, no matter how advanced. Deep space is simply too destructive to complex systems. We must content ourselves with probes and perhaps a little radio communication.

eniac and LJK . Fission is probably OK for probes/ ships launched from earth or the moon) but hard to see how we can sustain an effort from the outer solar system. Since i personally believe that , barring new physics, we will need to colonize the solar system out to the kuiper belt before we are able to launch world ships, then fission power makes less sense. but if i go with your premise that these ships launch from the vicinity of earth, then fission power is pretty practical and maybe even relatively cheap. Still it is hard to see how we would get over 0.5 % of light speed. here is a suggestion. do you think it practical to build ships/ probes to explore to the outer Kuiper belt /inner oort cloud using fission power? As detailed a few articles ago here, it is possible that there are some pretty interesting targets in the still largely unexplored outer solar system, and some reason to hope these may be the size of a super pluto or even mars or earth size. in any case these putative planets will be showing up in the Panstarrs and LSST surveys in the next decade. ( and in other places, not a complete list here) , should these bodies exist. I think that a probe to visit them would be an excellent bridge technology to your envisioned thorium powered deep interstellar craft. plasma / ion beam electirc rocket with a thorium reactor and medium sized heat exchange system.. may be do- able. and able to supply plenty of power for communications!

@Tom Lemon:

While you do have a good point in principle, I think you are overstating it drastically.

First of all, from decades to centuries is not really such a huge leap, compared to many of the other issues. Not enough to be labeled nonsense, anyway. Second, self-repairing systems need not be large, as any humble bacterium demonstrates. Exponentially larger? Exponential with what, time? Nonsense. As for that “Law of Ecosystems”, it does not exist. Unless you can provide a reference, I will relegate it to the nonsense category with your other claims.

The notion that space is harder on hardware than the “elements” on Earth is also questionable, I have mostly heard the opposite stated, but I am certainly no expert.

@JKittle:

Yes, an ion beam powered by a ultrahigh temperature radiation cooled reactor would go pretty far in terms of efficiency, maybe all the ways to the stars. However, the most efficient drive would be a fission fragment rocket, such as that described here: http://www.rbsp.info/rbs/RbS/PDF/aiaa05.pdf

As you say, it would be very hard to get to 0.5 light speed, you would have to go to large mass ratios, i.e. your ship would be 99% fuel. Luckily fission fuel can be made structurally sound, so that this is actually feasible. A total delta-V of 0.5 c might barely be possible, but that really means a flyby at 0.5c, a full stop at 0.25 c, or a return at 0.125 c. Certainly the disproportional increase in observation time makes the second option preferable, and we will just have to make do with that until a miracle occurs.

Tom Lemon: “The problem I see with these designs is that they are dramatically under-estimating, or just ignoring, the difficulty of keeping machines and/or biological self-contained systems viable in space.”

Very well said. High technology, as it exists today, requires a division of labor among hundreds of millions (at least) of people, and trillions of tonnes of machinery, on top of a closed ecosystem that can support all that. Designing a system that can repair a starship for thousands of years requires many advances and fundamental redesigns of almost every piece of technology it will have. And it will still be very very massive (fortunately still only requiring a miniscule fraction (10^-30 or so) of the mass of a dwarf planet for propellant, but that’s still orders of magnitude larger than Icarus). So in the end I disagree that this explains the Fermi “Paradox”.

What about muon catalyzed fusion as a viable fusion engine?

Although we cannot break even for power production, it seems to me that we could beam power at the vessel and use the power to produce muons and fuse the d-t fuel supply.

It might also be possible to use cosmic rays (electro-magnetically collected and focused ?) to produce the muons necessary for fusion with a net energy gain.

Pure speculation of course, but I have to wonder if more innovative ways to create a fusion drive might be discovered by independent teams not looking to create net energy fusion power stations on earth.

How about a fission reactor generating the electricity for ship functions and to run the fusion rocket for propulsion? Sort of a hybrid fission/fusion ship.

Eniac

Thanks for the ling to DPBFNR !

Great reading , with a bit of luck we are going to hear a lot more about that.

@Nick:

Like Tom Lemon, you have a good point, but I think, like him, you are blowing it well out of proportion. Perhaps you mean “High technology, as it exists today, UTILIZES a division of labor among hundreds of millions (at least) of people, and trillions of tonnes of machinery”. Requirements are almost certainly orders of magnitude less than what we use now. We can start be eliminating all the divided labor involved in the greeting card industry, for example, advertising, the auto industry, the oil industry, fishing, skiing, woodcutting, pencils, winter coats, umbrellas, etc. etc. Defense, too, and healthcare if we are thinking unmanned. After we have removed all unnecessary industries, we can apply automation to the rest to increase productivity (to infinity, if we are thinking unmanned), and miniaturization to decrease mass. As you say, redesigned processes will also help a lot. A few orders of magnitude later, we may find ourselves with something quite manageable.

In my opinion, and industrial “seed” can be fit into a few hundred tons of mass if everything is miniaturized to toy size. A good guideline as to how many different components might be needed is the protein repertoire of bacteria. They range from around 1,000 to maybe 10,000. An electro-mechanical equivalent may require more, but orders of magnitude more? It is hard to see why.

It would be fun to play a game: You name an industrial process you think is essential and uses at least a ton of equipment, and I try to come up with a reasonable idea to miniaturize it to the kilogram range or make do without it.

@Alex

There is no point in fusion if it does not produce net energy.

Eniac said on February 29, 2012 at 23:11:

“The notion that space is harder on hardware than the “elements” on Earth is also questionable, I have mostly heard the opposite stated, but I am certainly no expert.”

The cover and side of the Voyager Interstellar Record facing away from the robot probe are conservatively estimated to last one billion years in deep space. The side protected by the vessel will last even longer.

Our first deliberate message to ETI sent with a spacecraft, the plaques placed aboard Pioneer 10 and 11, may also last just as long. They were bolted to the antennae struts and face inward, using the probes as protection. By the way – Happy 40th anniversary of your launch today, Pioneer 10!

So yes, space is an excellent preservative, one which we should use to protect and preserve knowledge and information for future generations. Virtually nothing made by humans left on Earth will last as long here.

Obviously once you are either in interstellar space where there is much less debris and radiation to deal with than in interplanetary space, or buried deep inside a moon or other celestial body, erosion and decay slow to a literal crawl.

To give another example, the Long Now Foundation has placed identical examples of 1,500 human languages on discs made of titanium and nickel which only require magnification to read. An earlier version was placed aboard the ESA Rosetta comet probe in 2004.

http://rosettaproject.org/blog/02008/aug/20/very-long-term-backup/

To quote from the article linked above:

“So assuming the mission continues well, in 2014 the Rosetta Probe will land on Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, where it will measure the comet’s molecular composition. Then it will remain at rest as the comet orbits the sun for hundreds of millions of years. So somewhere in the solar system, where it is safe but hard to reach, a backup sample of human languages is stored, in case we need one.”

As anyone who studies history knows, there is so much we do not know about our distant past due to lost and destroyed records. We now have the technology to ensure this never happens again.

Oh yes – for those who would like to make their own message to ETI and/or future humanity:

http://www.wired.co.uk/news/archive/2012-02/27/pioneer-plaque-40-anniversary-competition

@Eniac There is no point in fusion if it does not produce net energy.

I understand your thinking, but that logic would preclude ion and thermoelectric propulsion systems, and beamed sails.

I would have thought that the issue was overall efficiency of the system. If fusion could be made 99% efficient with an external energy supply, that could be a useful propulsion system, but not a power supply.

Similarly with anti-matter. The energy cost of creating anti-matter might be many times the energy extracted, but it would make a very potent “fuel” or energy storage material.

I see that SpaceX went though a successful prelaunch test countdown today. Question: how difficult would it be for a private company to build a fission powered vehicle for trips from LEO to the outer solar system? what would drive the economics?

Well, if the Solar System was sscheduled to be paved over in 2022….

What could we build inside 10 years to escape ?

A- Today’s fission on ships boosted by lazer sails and full of frozen DNA and a biodome with a skeleton crew. They’d have only a slim hope of finding anywhere good before entropy kills them in some way. The first star had better be a nice one. We should send as many as we can to each nearby star, knowing most wiill die in the dark.

We are not competant enough yet. But in a century or two, we might have good engineering for the mighty tasks. Tasks for Hercules really.

Eniac: “Requirements are almost certainly orders of magnitude less than what we use now. ”

Not at all. Such an adjustment would, at minimum, require radical redesign of each piece of equipment, and even then (absent long-range and fundamental improvements in manufacturing, chemical processing, etc. technology) would be both more expensive and less functional than their earthside counterparts.

Again I highly recommend Adam Smith’s account of how a dizzyingly large network of incredibly diverse skills was required to make a simple peasant’s coat even before the industrial revolution, or Leonard Reed’s “I Pencil” on what is involved in making just the humble pencil. Or if you prefer a video, Thomas Thwaites’ TED talk on trying to build a simple toaster from scratch.

“After we have removed all unnecessary industries…”

Y0u have hardly demonstrated that any of those industries are unnecessary. Most of them are, for a variety of subtle reasons, quite necessary. And also for at least one reason that should be obvious: every industry you eliminate makes the spaceship economy that much more living in poverty relative to earth. Some degree of relative poverty is a practically unavoidable outcome of a smaller closed economy anyway, but it’s hardly useful to dismiss it with a handwave and a shrug and pretend it doesn’t have consequences for attracting talented colonists or later maintaining the wealth need to support the high technology needed to repair ship systems over thousands of years.

‘In my opinion, and industrial “seed” can be fit into a few hundred tons of mass’.

You’re off by at least twelve orders of magnitude, and probably far more than that.

“It would be fun to play a game: You name an industrial process you think is essential and uses at least a ton of equipment, and and I try to come up with a reasonable idea to miniaturize it to the kilogram range or make do without it.”

“Reasonable ideas” don’t cut it in this area. The devil is in the details — replacing each part in each machine in an economy (i.e. replacing billions of trillions of parts in hundreds of millions of varieties) with a far smaller diversity of parts made in far smaller batches, yet somehow no more expensive or less functional. Good luck with that!

Effectively the thing that will, very slowly, overcome this problem is a millenium or so more growth in industrial productivity at the rate (c. 2-3%/year) that it has grown over the last millenium.

@Eniac,

I’m always shocked by how oblivious most space advocates are to even the simplest engineering issues involved in space survivability of complex systems. If you talk to NASA engineers, who work on any type of space equipment, they can talk forever about the horrible difficulties they face, as engineers, keeping a space probe alive for even a decade or two. Yet you blithely talk about hundreds of years, as it if will just magically happen.

I bring up issues like “vacuum welding”, “diffusion of volatiles into vacuum” and I hear nobody offering to discuss them realistically. Each of these issues, by themselves, is quite capable of killing off any interstellar probe project you care to name. Each of them is a engineering problem that could easily push your projects off the charts of viability (it’s that exponential factor again, sorry).

Somebody mentioned the recording on the back of the Voyager probe…which is kind of a funny thing to talk about, because it completely proves my point. .The record on the back of Voyager is a simple hunk of material. It is not a complex system. That format (a simple record) was chosen by engineers because it was the only format they could imagine that *could survive* the rigors of deep space. Other more complex formats — magnetic tape, semiconductors, mechanical systems, etc — all of these would be destroyed very quickly by radiation, dust, atomic creep, etc.

The fact that somebody would use the Voyager record as an example of survivablity tells me that they have zero understanding of the question.

Then you said:

“Unless you can provide a reference, I will relegate it to the nonsense category with your other claims.”

Sorry, but you’ve got it backwards. The burden of proof isn’t on me to prove anything. The burden of proof is on *you* to provide references to back up *your* claims.

I’m stating the established and conservative viewpoint, backed by 50 years of horribly difficult engineering at NASA and other places. Space is incrediblity hostile to complex mechanical or biological systems. You on the other hand are the one making fantastic and unsupportable claims. You seem to think that travel for decades in the radioactive hell of deep space, enduring the incredibly destructive effect of cold, dusty vacuum, and the impact of dust and debris at 10% the speed of light (or whatever) is a casual engineering problem. Not one qualified space engineer would agree with you. Most good engineers would say “you are underestimating the weight of your craft by a factor of 10” — just as I did.

So, please provide references to support *your* claims. Until then, well you might as well just be an episode of Star Trek — you know, the one where basic physics and engineering is ignored in order to allow the Captain of the enterprise to go zippping across the Galaxy in pursuit of green skinned girls. Sure, it’s fun. But no relation whatsoever to reality.

The Challenge of Interstellar Spaceflight

Posted on March 1, 2012 by launiusr

An artist’s conception of traveling through a wormhole.

The prospects for any interstellar flight by humans or their machines seem exceedingly remote. Nonetheless, the inclination to contemplate interstellar travel remains strong. In fact, interest is likely to grow, as a consequence of current research of the nature of the galaxy and the revised view of its cosmic neighborhood that will certainly follow.

While there is growing interest in interstellar flight, the practical difficulties of achieving it have caused some people to abandon the challenge and ask whether any stellar travel may be possible. The results of such detachment, to say the least, are fascinating. Once one removes the requirement that the travelers be human or under human control, interesting possibilities emerge. If creatures from Earth venture into the galaxy, they may do so in ways that depart considerably from conventional views of rocket travel.

There are basically only four methods for humans to travel beyond the solar system:

Faster than the speed of light (warp drive or wormholes).

Multigenerational spaceships.

Suspended animation.

Extremely long-lived species.

Full article here:

http://launiusr.wordpress.com/2012/03/01/the-challenge-of-interstellar-spaceflight/

Billions of trillions of parts? Please name just 1 trillion of them :-)

I hope you see that claims like that are so hopelessly exaggerated that they cannot be taken seriously. Not that you don’t have a good point qualitatively, but your quantities are way off. By billions and trillions, really.

So, you are saying that the advancement of productivity in the next millenium will be the same as in the last? The move from paper to information systems, from horses to nuclear power won’t make a difference?

I believe you are in for a surprise.

Eniac, let’s run the numbers. Have you ever thought about how many objects you actually have in your household? Furniture, electronics, machines, toys, artwork, pencils, utensils, food, drink, clothing, etc. — every physical thing processed by man possessed by someone who lives in your house.

I’m a typical average income American and I have tens of thousands. (Heck,in the building toys for my kids I easily have over ten thousand right there, and my collection of hardware store parts is even larger than that, and those are just three out of the dozens of boxes in my garage and closets). Now how many components in each object? It’s quite easy to grossly underestimate this number. Even simple parts like Lego bricks and screws are made out of a witch’s brew of material ingredients. More complex devices like your computer and car are made of parts, made of more parts, made of more, etc. often exploding down many levels, and even each part tends to be a mixture of many different materials, as well as being coated with many more materials still. So each such device easily has many millions of components (even if we count a chip as a single part rather than counting all billions of circuits and transistors in most chips). The humble pencil, if you’ve read ,your Reed, contains tens of parts and material coatings, each made of mixtures of many different materials — call it 200 components.

If the average object out of the c. 100,000 in my household has 10,000 components, that multiplies out to a billion components per household. Multiply that times a billion households, all part of the division of labor necessary to produce such a large number and variety of these components, and we get a million trillion components. For the industrial and office plant needed for the production, distribution, recyling, etc. of all this, and of all the supporting services, and all the equipment therein, and all the equipment needed to make all that, etc., multiply by a further 10.

And that’s just the instantaneous amount — if each component lasts on average 10 years, multiply by another 1,000 for the number that need to be made, distributed, used, and recycled during a 10,000 year mission.

As for variety of such components, just in my household that’s not radically less than the number of instances, but if we counted it across the entire economy it would be. 100 million varieties is probably a serious underestimate.

So in our interstellar colonization starship, using the same kind of technology (and thus the same very high division of labor that makes it) at the same level of wealth we have now for the colonists, there will be 10 billion trillion instances of components in over 100 million varieties that have to be made over a 10,000 year period. Unless you can figure out how to radically redesign practically each and every such machine and part therein, all the way down, in all its detail. Good luck with that!

As a lurker (and not a worker in any of the relevant fields) my opinion may not amount to much, but I wonder if we all ought to take a moment and cool our heads a bit. Clearly this is a difficult issue and the technological hurdles are not likely to be resolved, by whatever model would resolve them, in most of our lifetimes. Nick raises some good points, if stated rather bluntly, that I think all us enthusiasts could do with giving a listen. Likewise, I don’t think bickering over who has the more ridiculous claim is going to get us anywhere productive, either. Lets put egos aside and play nice, gentlefolks.

This thing is going to be a bugbear for a long time yet. I’m interested to hear a little more about the specific processes involved in space weathering–how does vacuum welding happen, for instance? Are there materials more or less susceptible to it, or is the only reasonable solution to eschew moving parts so far as possible (correspondingly, how does solid state equipment fare in the radiation environment? Bit flips seem like the primary issue to surmount there. How much shielding to mitigate bit rot on a fixed amount of material per decade?) That sort of thing gets aired in these pages all the time, but there are, without question, issues we haven’t even encountered thus far in the design of such a thing; billions of parts may not be so far off in the fullest account. Orders of magnitude get thrown around a lot, which is to be expected when one is talking of something so superlative to begin with.

It is tempting to believe some of this could be addressed by sufficiently clever approaches to the problem–what if one were to hollow-out an existing cometary body for the probe to use as shielding and raw material, for example? How much uranium et cetera is out there in the asteroid belt? And so on. Ultimately that’s what engineering boils down to: sufficiently clever approaches to difficult problems. For something like Icarus we’re almost certainly talking about system-wide infrastructure and fabrication facilities, neither of which is strictly near term (and aside from certain “Fab-Labs,” automated small-scale fabrication doesn’t seem to be pursued all that seriously at the moment). Some development on this scale is probably necessary before anything like what Icarus is proposing becomes feasible–at that rate, we’re looking for some kind of phase-change in the economy, one which we are presently on the other side of (if it’s going to happen at all). Trying to do it with a strictly Earth-centric industrial complex seems silly to me, but predictions are necessarily messy from here. Whatever the soution(s) end up being, they’ll be a long time coming. Tasks for Hercules, indeed.

This is one of the reasons why I am so enthused by the existence of a Project Icarus, and Daedalus, Orion and so forth, because we don’t have a lot of collated numbers and qualifiers on these things, just scattered sources over a couple centuries worth of relevant academe.

I’d like to see a little more done toward that kind of data-collection project in addition to things like Icarus. Surely no one group of people is going to be able to quote you every relevant study for something as complex and context-dependent as an interstellar probe; having a central clearinghouse or library of all the disparate material would in itself be a positive outcome in the biggest way.

Regardless, the point isn’t that it’s hard to do (it is), but that someone is finally trying to think seriously about how one might do it, which I applaud. The more seriously we can think about it, and the more strictly we apply ourselves to the realities of the problem, the better. At the same time, we must keep applying ourselves to the problem, so a certain amount of optimism and willingness to entertain a fancy or two, if briefly, seems essential.

All right, enough of my ranting, back to lurking for me. Ad Astra Incrementis!