Sara Seager’s thoughts on who might join a crew bound for Alpha Centauri have had resonance, as witness Dennis Overbye’s story Discovery Rekindles Wish for a Journey to the Stars in the New York Times. Overbye, a touchstone in science journalism, has probably been pondering the issue because of Seager’s response to his question about Centauri B b. The MIT astronomer laid it out starkly: “I think we should drop everything and send a probe there.”

Seager is well aware of the issues involved and knows what a project it would be to drive a lightsail — or some other kind of spacecraft — up to ten percent of the speed of light. But she has us all thinking about the kind of people who would go on future manned missions (and whether they might wind up changing their minds). Overbye can look back at his high school yearbook, where he finds “Ambition: To go to the stars.” These days he’s thinking more about what would happen if he really did:

Perhaps it is a sign of my age that I think more these days about what I would be leaving behind than what I would be gaining: my family and other loved ones, autumn in the Catskills, one more cowboy trout stream or New Year’s Eve with old friends.

What about Mae Jemison, the former astronaut, engineer and actor who now leads the 100 Year Starship organization? Working with Icarus Interstellar, she landed a DARPA grant for $500,000 to plan for an interstellar mission, and it turns out Centauri B b was announced on her birthday. Thinking about those trout streams and mountain autumns, Overbye asked Jemison if she would want to board a starship, knowing that she could never return. Her response: “Yeah… I would go.” But she was quick to add: “It makes a difference who goes with you.”

Image: 100 Year Starship’s Mae Jemison.

Would we bring enough of our own culture along with us on an interstellar journey to create a truly livable environment aboard the craft? Jemison think so, saying that our ideas about such trips have to be reimagined, but it’s hard to see how any conceivable star journey at 10 percent of lightspeed could be a comfortable experience, though perhaps bearable with some kind of hibernation technologies. Much longer trips are another matter, for a sufficiently advanced civilization could think in terms of gigantic worldships that re-created Earthly habitats and, on millennium-long journeys, supported many generations of spacefaring humans.

Overbye acknowledges that all of this is daydreaming, given the current state of our technology, but sketching out a vision helps us understand the problem and question the tentative solutions. Seager’s enthusiasm for a future probe to Centauri B b reminded me of planet hunter Geoff Marcy (University of California at Berkeley), whose numerous exoplanetary finds include fully 70 out of the first 100 to be identified. It was Sara Seager who urged a 2011 MIT workshop to be provocative, leading Marcy, who was in attendance, to say this about star probes:

“I’d like to make an appeal to President Obama. I think he should stand up and make the following announcement: That before the century is out we will launch a probe to Alpha Centauri, the triple star system, and return pictures of its planets, comets and asteroids, as soon as possible, even if it takes a few hundred years or a thousand years to get there. [Going to Alpha Centauri] would engage the K-12 children, it would engage every sector of our society… It would jolt NASA back to life, if we’re really lucky. And of course any such mission should be an international one involving Japan, China, India, Europe…”

Marcy told the same audience that the key for the future of exoplanet studies was to get spectra of nearby stars. Staying close to home allows us to measure the atmosphere of these exoplanets once we have the space-based instrumentation in place. Moreover, proximity means we’ll be able to distinguish them from the zodiacal dust in their systems because as we study that relatively close dust, we’ll learn how to subtract its signature to resolve any Earth-like worlds more clearly. We need the ability to home in on planets within 25 light years not only for pure science but because these are the planets that, we hope, will be reachable by future propulsion systems.

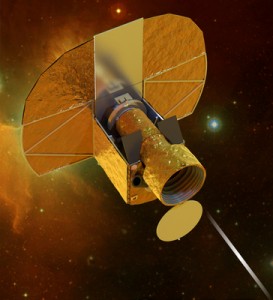

Bear in mind that the 2010 decadal survey New Worlds, New Horizons in Astronomy and Astrophysics made no mention at all of the Terrestrial Planet Finder mission. But just the other day we had news that Cheops had been designated as a new mission by the European Space Agency, with launch expected in 2017. Cheops – for CHaracterising ExOPlanets Satellite – will look at the kind of stars Marcy is talking about, nearby bright stars known to have planets. Hunting for transits, the mission will measure planetary radii and, for planets whose mass is known, reveal their density, which should tell us something about their internal structure.

Image: An artist’s impression of the Cheops telescope. Credit: University of Bonn.

The plan is to operate Cheops in a Sun-synchronous low-Earth orbit at an altitude of 800 kilometers, with a mission lifetime of 3.5 years. Alvaro Giménez-Cañete, ESA Director of Science and Robotic Exploration, says that “By concentrating on specific known exoplanet host stars, Cheops will enable scientists to conduct comparative studies of planets down to the mass of Earth with a precision that simply cannot be achieved from the ground.” We can hope that as more planets are found around nearby stars, other new missions will get funding, and the zeroing out of Terrestrial Planet Finder will one day be seen as only a temporary setback.

Quoting Paul Gilster from his article above:

“Would we bring enough of our own culture along with us on an interstellar journey to create a truly livable environment aboard the craft? Jemison think so, saying that our ideas about such trips have to be reimagined, but it’s hard to see how any conceivable star journey at 10 percent of lightspeed could be a comfortable experience, though perhaps bearable with some kind of hibernation technologies. Much longer trips are another matter, for a sufficiently advanced civilization could think in terms of gigantic worldships that re-created Earthly habitats and, on millennium-long journeys, supported many generations of spacefaring humans.”

Maybe I missed this, but what about virtual reality? Star Trek sort of had it right with the holodeck, but what about immersing people into virtual worlds of their own choosing, so that they could experience life on their own terms?

I am sure there are plenty of issues with this idea, but people seem once again stuck on the old paradigm that a starship crew on a very long journey will be sitting around twiddling their thumbs, perhaps surrounded by decks of playing cards and a few board games. Our technology should be employed to entertain and distract the crew for such journeys.

What about if they choose to remain aboard their Worldship, visiting worlds only to study and resupply briefly? I think I would rather have the option of roaming the galaxy instead of just going from one rock to another.

Keep in mind that on a multigenerational starship, people born during the journey will only know the ship and crew as their home and family. Earth and any destination worlds will be something they only learn about and never experience directly.

As for these generations who live and die in space, will they be happy enough to know their main purpose is to create the next generation of children for the journey, or will they resent their limited roles and take action?

I am not even going to touch the subject of mind uploading, as it has already been covered elsewhere in this blog to the point of being mind-numbing .

…President Obama. I think he should stand up and make the following announcement: That before the century is out we will launch a probe to Alpha Centauri, the triple star system, and return pictures of its planets, comets and asteroids, as soon as possible, even if it takes a few hundred years or a thousand years to get there.

Pretty pointless. Politicians can say anything about goals that will be long forgotten after they are out of office. Furthermore, a probe that took that long will probably be passed by faster probes/different technology in the future. The costs would be high, the payback so far in the future that the discounted economic value would likely be almost nil.

I would rather build telescopic platforms so that imaged data, for many stars could be developed first. That would be more exciting, immediate, and bring the payoff to the near term.

When we do send probes, I trust the technology will make our current ideas seem as quaint as Victorian musings about steam powered flight. Spending a lot of resources on a slow probe is equivalent to spending on guns rather than butter.

On another quote from this article by Paul Gilster:

“It was Sara Seager who urged a 2011 MIT workshop to be provocative, leading Marcy, who was in attendance, to say this about star probes:

“I’d like to make an appeal to President Obama. I think he should stand up and make the following announcement: That before the century is out we will launch a probe to Alpha Centauri, the triple star system, and return pictures of its planets, comets and asteroids, as soon as possible, even if it takes a few hundred years or a thousand years to get there. [Going to Alpha Centauri] would engage the K-12 children, it would engage every sector of our society… It would jolt NASA back to life, if we’re really lucky. And of course any such mission should be an international one involving Japan, China, India, Europe…”

Not doubt I am just a major league pessimist when it comes to politics and especially the kind involving United States Presidents, but I do not see this happening any time soon, except as some throwaway comment to sound impressive but meaning nothing and certainly no funding for it.

No President since Kennedy has promoted any kind of major space effort that survived (and even JFK didn’t care much about space exploration). Yeah, yeah, I know Reagan made some soaring comments about what would become the International Space Station, but talk is cheap. Anything that lasts more than two Presidential terms in office tends to get lip service at best. And a round trip mission to Alpha Centauri even at 99% lightspeed will take over eight years to accomplish. Plus I don’t think there are any registered voters in that star system.

We already know that Romney and Ryan would add nothing new to NASA, including and especially funding – but he would give the Department of Defense two TRILLION dollars on top of the 700-plus billion they already get EACH YEAR. The general public still thinks NASA gets too much money and they continually fail to see the benefits of space exploration and utilization, as shown here:

http://amyshirateitel.com/2012/09/28/the-cost-of-curiosity/

Do not forget Romney’s infamous comment about firing any employee who came to him with the idea of a manned lunar base such as the one Newt Gingrich proposed earlier this year, where he was roundly criticized and ridiculed for it by just about anyone who was not a space advocate. So much for progress in the fifty years since John Glenn circled Earth three times for America.

If there is any hope at all for any kind of interstellar mission, it will be from and by people like the rich guys who want to exploit the planetoids and/or one of the spacefaring nations that still have colonial ambitions.

Jules Verne and the submarine is probably the best example of someone with a good imagination and some practical knowledge forecasting a future event. We are probably capable of the same forecast now in regards to star travel.

It seems to me that the only source of energy able to send us to another star is the H-bomb and this is likely to remain the case for quite awhile. H-bombs pushing a ship carrying a frozen crew at perhaps 10 percent but no more than 30 percent would be reasonable. The crew would be shielded by a great deal of water, 20 or 30 feet, and would have to be revived at intervals to allow their bodies to repair DNA damage.

This indicates (to me at least) that freezing people without damage and reviving them is the only piece of missing technology. Such a procedure would change the human condition profoundly as delaying the death of loved ones until a cure for old age and other conditions could be found would become a basic human right overnight. We would become very busy building storage facilities and changing our global priorities.

We need planetary targets to which to send probes.

Not probes to search for planetary targets.

A thousand years of transit time? That’s no good unless it’s the only way for people to escape a doomed earth.

Spend the money on bigger telescopes and propulsion research.

Humans as we are presently constructed are only good for life on earth, or an Earth Too. I suppose that if the Singularity occurs and we are given space legs, anything is possible. Flesh and blood humans need grass and blue sky with gravity set at 1.0

To Gary, If we’re able to “freeze” people and prolong life, that only adds initiative to colonizing space. Less deaths + More births = No room on our planet to support it. I’d love to see an international effort to build a moon-based telescope as that’d give us even more reason to be in space and it’d be a start for more complicated tasks like mining.

I found the position of Sarah Sager and Geoff Marcy astonishingly irrational for astronomy professionals. For a miserable fraction of the cost of “dropping everything and send a probe there” we can characterize and possibly image all the star systems to 15 pc and beyond and, maybe, find a better target than a barren lava world.

My consideration for them is seriously diminished. Survey first, then send a probe (maybe).

And the article (discussed here) from Philip Horzempa

http://www.thespacereview.com/article/2170/2

Again claims that a FOCAL mission would have a 1 meter resolution at Alpha Centauri. If true it seems a better option than a probe for a LONG time.

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: Space exploration needs an ideology bordering on a religion to really motivate people to get off this rock. I’m thinking of someone like a “galactic Mohammed” who inspires humanity to conquer the universe for the sake of a new belief system. There have been hints of such an ideology from a few space fanatics, but it’s all a bit too tame and rational to really get people into high gear. Enlightenment thinking may be counterproductive here, since at this point the whole enterprise of interstellar space exploration is a leap of faith. Our greatest achievement in space to date, the Apollo program, was an irrational product of our power struggle with the Soviet Union. Does anyone regret that it happened? What about the building of the Great Pyramids? What do such things tell you about human motivations?

What would the world be like if our leaders believed deeply in humanity’s cosmic future, instead of myopic, Earth-centric Bronze Age myths? I would even settle for a “galactic Genghis Khan” at this point who aspires to build the first space empire. Don’t you think that without aggressive “space evangelism” to memetically transform our society, your project will be hard-pressed to find funds and support from a population indoctrinated to believe that their kingdom is in the next world? Humanity seems strangely asleep and small-thinking at this crucial moment in history, as if it awaits the coming of the space messiah. I believe there is a huge missing piece to this Centauri Dreams puzzle, and it’s name, for lack of better words, is “cosmic religion”.

In regards to religion, actually a thread of Russian Cosmism begins with Federov and continues on with Tsiolkovsky. Cosmism was all about ”the singularity” a hundred years ago.

I believe sending probes to the stars does not have to be the big huge one-time effort that it is often made out to be. In a sense, we have already sent some probes to the stars, albeit they would take 73,000 years to arrive and not be functional at the time. The key is the realization that these probes would have uses before they even leave the solar system, for long-baseline interferometry, parallax measurements, and fly-by observations of multiple planets, moons, asteroids, and the like. Next up is the Kuiper belt, Oort cloud, the sun’s gravitational focus, sampling of interstellar medium, and probably dozens of other interesting missions I am not thinking of.

Driven by these missions, our probes will get faster, smarter, and more long-lived. We might close the current gap of three orders of magnitude between mission time and survival time to Alpha Centauri before we know it. We might get our first data from close to another star on the cheap, according to an extreme version of the “extended mission” model that has worked so well elsewhere in space exploration.

I’m afraid i have to partially agree with Darth Imperius. Probably we need a new Scientology or the Bene Gesserit, i mean in the sense of a anthropologically engineered religion to fulfill a wider sociologic goal.

While I have said elsewhere in this blog that it will probably be a cult that first ventures to the stars, we should be more than a little concerned if other intelligences have similar notions, especially if they are big on trying to convert others.

If such a missionary starship showed up now, we could be a in a lot of trouble, as all they would have to do is attach some rocket motors to a few sizable planetoids, aim them at our cities or perhaps an ocean, and then “suggest” that humanity share in their faith.

One thing I am willing to bet on, human or otherwise, anyone who sends more than a robotic probe into interstellar space is not doing so purely on altruistic, scientific grounds. Should an alien Worldship come here, maybe they just want to refuel and do some studying, or maybe they want to “save” us from ourselves.

In response to Darth Imperious:

I recently saw a performance by the venerable punk rocker Genesis P. Orridge in which he sang a folk-rock anthem called “Mother Sky” which talked about space in the same terms which are usually used to refer to Earth. “I dwell beneath Mother Sky”, “I give thanks to Mother Sky”, “soon we will ascend to our home in Mother Sky”.

It struck me that thos us a wonderful illustration of the fundamental cultural shift we would need to make to become a true space faring society.

A Space Nation should be started with people free to join and leave. If a citizen you can vote on priorities and proposals, pay a percentage of you income, and fund activities to bootstrap your descendants into space. Things would start small with volunteers and achieve reachable goals, but with time a functioning settlement could be started with a non-Earth Nation governed population. Becoming a citizen early gets you further along in the queue and its setting up a Government that could seamlessly transition small settlements to self government in the long term. No being beholden to Earth Nations and avoiding setting up a confrontation between settlers and Earth down the track. I think this is better than a Religion or Overlord model, which I can’t see working in the massive expanse of Space. I can’t see today’s countries pouring resources into space, because space isn’t owned by them. It will be owned by the citizens of space itself.

We need to invest more on telescopes that can detect new planetory systems

insted of sending probes to detect it.

Perhaps if we want our children to reach for the stars, they should have some idea where their home planet is located in the Universe first:

http://nasawatch.com/archives/2012/10/are-gen-xers-lo.html

“Less than half of Generation X adults can identify our home in the universe, a spiral galaxy, according to a University of Michigan report. “Knowing your cosmic address is not a necessary job skill, but it is an important part of human knowledge about our universe and–to some extent–about ourselves,” said Jon D. Miller, author of “The Generation X Report” and director of the Longitudinal Study of American Youth at the U-M Institute for Social Research.”

@Kawan

Perhaps you don’t read SF. “Why Call Them back From Heaven” by Clifford Simak addresses the issue of keeping the living population manageable by freezing much of the population.

I have to say I am very much amused by all the ideas about how we ought to become space-faring by the enslavement of populations. Whether it be religious indoctrination, power hierarchy, or “freezing” or otherwise keeping them out of the way of their self-appointed superiors, it is enslavement. What ever happened to liberty and justice?

When there is a good reason to go, and people are educated and free to choose to go and/or invest, it will happen. That choice could be private (individual or corporate) or public (democratic society). Frankly, any talk or coercing or tricking people into compliance to another’s will is something I find to be reprehensible.

@Alex I read SF just not that extensively. It all starts to sound the same after awhile but cryogenics is wayyy over my head so I could be wrong. Hibernation for space travel and hibernation for population management aren’t the same and I’m only assuming (without reading) that the latter would be a lot more expensive than simply starting an off-world colony. With population management we’re talking about having to freeze and thaw millions, maybe billions of people. Whereas in space, after the foundation is set, we could simply just move from one spot to the next and leave hibernation to interstellar travelers.

I have to agree here that talking about probes seems to be counter-productive.

What we need and CAN do is advanced space telescope technology, which would allow us to gain much more information,much faster and faster than any probe that we can send in foreseeable future.

Probes are not what we should be aiming at currently.

I repeat that the planet of Alpha B is even more totally useless than Venus:

1. It’s red hot, so we can never land there.

2. It has high orbital velocity due to its close distance to B.

3. It probably migrated from farther out, perhaps disrupting more suitable planets.

If this planet is all that Alpha Centauri has to offer then we’ll never go: we need both asteroids and a cold gas giant, since without them we’d starve.

“With population management we’re talking about having to freeze and thaw millions, maybe billions of people.”

It is not “management” that I refered to- it is stopping people from dying until a cure for their illness is found. Of course old age is the ultimate killer and I believe the figures are over 50 million per year. We would be freezing that many people and racing to find a way to reverse aging so we could wake them back up again.

As for managing the population, the solar system has the resources to support tens of billions in habitats. I like Bernal Spheres that spin to provide gravity on the inner surface at the equator. These Spheres can also, if made for it, can also be pushed by H-bombs to some percentage of C and the inhabitants frozen for the trip to other systems.

How do we even get those tens of billions out into space? Beam propulsion is about the only technology that appears to offer the solution with single stage to orbit vehicles go up like airliners (but probably not coming back again). They actually might be very large vehicles carrying several hundred or even thousand people at a time into space.

I used to be sceptical about the idea of a president calling for a mission to Alpha Centauri in 100 years, but now I think it would at least plant a strong signpost to the future of our efforts in space.

It would be a vision that future generations can return to. It doesn’t mean committing vast sums of money right now when times are hard – but it is at least a mission statement that will inspire the young.

Also, I don’t see a mutual exclusivity between an interstellar probe mission and solar system missions that include something like FOCAL. There is no need to ‘drop everything’; these are all stepping stones to making interstellar flight a reality.

@Interstellar Bill:

I think that nobody here is contesting your points 1 and 2, nor your last sentence.

The real crux is in your point 3 and that remains the question: are there other (terrestrial) planets farther out or have they been prevented or disrupted in an early stage? Time will tell.

I wouldn’t be surprised if there indeed appear to be more planets in wider orbits around B, but that these planets are super-earths or bigger. Previous HARPS research has already revealed that there are no planets larger than 4 Me in the HZ (up to about 300 day period) and various computer modeling indicates that gas giants are unlikely anywhere around B (or A), but there could be super-earths between 2 and 4 Me in the HZ and larger planets outside the HZ, up to about 2-3 AU.

I am saying this because of the high metallicity of the Alpha Centauri system (about 60% higher than solar) which seems to indicate more abundant (proto) planetary building material, unless this high metallicity is an indication of ‘secondary stellar enrichment’ by planetary material being absorbed by the star, as has been suggested by some studies, not only for Alpha Centauri, but also for high and/or peculiar abundances in solar twins (Melendez, Ramirez, Asplund, et al.).

Further to my previous comment:

In the case that very high metallicity is indeed a result of ‘secondary stellar enrichment’, i.e. (proto) planets having been disrupted by the eccentric stellar couple and/or inward migration of a planet, and subsequently having been absorbed by the star, this would mean that Alpha Centauri B (and A) may indeed show a paucity of planets.

This secondary stellar enrichment would also explain the lack of any detected planets (so far) around the single solar type star Delta Pavonis with its very high metallicity.

I checked some articles on computer modeling of planetary formation around Alpha Centauri and found that the combination of the small (closest) distance between A and B and their high eccentricity do not look very promising for long-term stable planetary systems in the HZ of either.

Of course there is still realistic hope for an earthlike planet in the HZ, particularly for B, but we should expect to have to travel farher to the nearest habitable earthlike planet, a lot farther.

That’s an interesting idea about asking the President to support a mission to Alpha Centauri, but how about this, Ban Ki-Moon supporting a mission to the nearest planet outside our solar system. As the NYT article said, leaving our solar system (and even Earth) makes us Earthlings, not Americans, Chinese, etc. Time to start thinking internationally and even globally, or we will be forever confined to our crib, the “pale blue dot”.

I am a frequent but irregular reader of Centauri Dreams so maybe I’ve missed this, but has Hibernation or safely freezing travelers ever gotten any attention here? Is anyone doing research on this in a way that would be meaningful for space travelers?

“has Hibernation or safely freezing travelers ever gotten any attention here?”

If I keep commenting here it will.

As for anyone doing research, it is not being done probably for a combination of reasons- the most important one being that there is no fast money to be made with it. If you look at what is going on in the world of research you will find two poles- “basic investigation” and “money to be made.” Freezing someone and then reviving them does not fit into the first and causes more problems that it is worth in the second.

And then there is the giggle factor that cryonics has instilled.

Regarding cryonics, etc.: I know nothing about such things, but I have the impression–perhaps based more on television and film than real life–that there would be potential for angel capital via the eccentric billionaire’s club. Several exceptionally affluent Singularitarians come to mind.

One idea that I had, while looking at lunar data and realizing that there are niches with stable cryonic temperatures, was for a cryonics vault on the moon which would provide a stable environment for perhaps millennia, without the input, and other requirements which are significant risk factors for current cryonic storage.

Another silly idea occurred to me when reading about fish wish antifreeze in their tissues. Apparently proteins that inhibit ice crystallization. I imagined a gene therapy, or some such thing, that would saturate particularly vulnerable tissues (e.g., brain) with otherwise inert “antifreeze” proteins. I do have some realization of how far-fetched this idea is, but I’m just some random guy who has thought about this stuff for five minutes. My point is that there must be things that a well-funded projected could pursue which would be “game changers.”

Wishing I could edit the typos in my previous post. Apologies.

“there would be potential for angel capital via the eccentric billionaire’s club. Several exceptionally affluent Singularitarians come to mind.”

It is great conspiracy theory stuff to imagine we can already freeze and revive but the elites are keeping it suppressed and only allowing it for themselves. But I think it is just a matter of it not being treated seriously because no one will fund it. What do you do with it if it works? It is the ultimate disruptive technology. If you want people marching in the streets just tell them they can save their loved ones from dying and people can have an unlimited lifespan- but only if they are rich enough.

That’s an interesting point. I don’t follow these things very deeply, so maybe this just a reflection of my ignorance, but it seems that the huge sociological implications of things like cryonics, or radical life extension, are too often ignored. I suppose it isn’t a major issue until such things actually become feasible. Kind of makes sense. Still, yeah, what would the world be like if such technologies were real? My mind is tending toward somewhat dystopian scenarios. But are such fears good arguments against developing such tech? Paradoxically, I’m not inclined to think so.

It worked for the ancient Egyptians. Well, except for the part where it actually works, of course, but they made it happen nevertheless.

“what would the world be like if such technologies were real? My mind is tending toward somewhat dystopian scenarios. But are such fears good arguments against developing such tech? Paradoxically, I’m not inclined to think so.”

I am inclined to believe that this is the next step for humankind and think of it as the second coming. But most people I discuss it with are dismissive and do not like it. I don’t understand this reaction at all. It is depressing.

GaryChurch said on October 31, 2012 at 16:06:

“what would the world be like if such technologies were real? My mind is tending toward somewhat dystopian scenarios. But are such fears good arguments against developing such tech? Paradoxically, I’m not inclined to think so.”

“I am inclined to believe that this is the next step for humankind and think of it as the second coming. But most people I discuss it with are dismissive and do not like it. I don’t understand this reaction at all. It is depressing.”

Because since the late 1960s and the rise of the counter culture, it is no longer cool to think the future will be like the Jetsons. The public almost willingly accepts a future that is something akin to The Matrix series, the Terminator series, the Mad Max series, or The Walking Dead, but tell them we can live on other worlds and that war and disease and poverty can be eliminated if we work together is seen as crazy fantasy.

Our priorities are out of whack. We will create the very dystopian future we claim to dread yet are secretly intrigued about if we continue to think we can sustain our civilization on this one planet while our population grows and our resources and land remain finite.

“We will create the very dystopian future we claim to dread ”

I witnessed a tatooed and very smelly young man in the Seattle public library raging against civilization last year in the Seattle public library. He said he could not wait for the whole thing to fall apart. I was thinking about starships when I was his age- not the cannibal apocalypse. Which is exactly what we would have if civilization collapse; billions of people eating other till there were no longer billions trying not to starve to death. It is what people do but do not write in the history books afterward.

GaryChurch, it sounds like this person has a literal death wish. Instead of committing suicide, though, he wants society to do it for him while it brings itself down in the process. Frighteningly there are many others who think and feel as he does. How many will it take to bring about such a cultural collapse?

This is just more evidence that human technology and population numbers have wildly outpaced our biological level. We are still best suited for small tribes, but modern global civilization no longer allows that. Can we grow into our current world, or will too many end up dropping out or never achieving the necessarily levels to sustain our society?

Today’s civilization is not offering much comfort. Along with our poor global economy, which keeps playing with a full blown depression if not outright economic collapse, the past methods of giving humanity hope are dwindling and failing all around.

Religions no longer have the same impact or control that they once did – and most people still need some form of this despite what others may tell you. Our political leaders seem more fallible than ever – though most of them always were, only they were not under the microscopes our media now puts them through. One gets the strong impression that only the really rich of certain races can ever attain serious political office and that their primary goal is to keep themselves in power.

Our space efforts, initially viewed as a major hope for tomorrow, are now more often seen as retro and containing intangible benefits to our species. NASA has no definite goals despite their claims to the contrary (CGI of some big fancy rocket is not a goal). Russia may never get back what it once had with its space program, despite declaring such goals as a lunar base every so many months. China’s space program will be for China; if they ever allow anyone else to participate in more than a token manner, it will come at a very high price. India’s space program and private space efforts have potential but whether they can translate it into actual colonization remains to be seen. I still cannot get out of my mind the across-the-board ridicule that was dumped on Newt Gingrich’s manned lunar base statement earlier this year.

Most telling of all, our modern culture looks upon an optimistic future as something akin to naive hope from our grandparents’ past. It is so much cooler to imagine a world run by an iron-fisted dictatorship complete with gun-toting faceless soldiers marching through damp and depressingly-lit streets, or a civilization overrun by flesh-eating zombies or survivors duking it out in the radioactive rubble of a post-nuclear holocaust city.

Ironically, this stems from a desire by many to return to a perceived simpler and therefore happier time, something I call akin to an eternal camping trip. How many modern people would actually survive the shock of going from a hi-tech civilization to living in tents or caves and foraging for food would be a frightening exercise. Those who would be left might not exactly be the shining examples of a more humble and noble humanity. How long would it take the human species to “recover” from this change, if ever? Certainly we would be much more open to extinction-level events such as unchecked diseases and celestial impacts.

We really are at a cultural, global tipping point. We could achieve greatness and a happy, balanced society, if we can shed our old attitudes and give people real hope again. We who are promoting the starship concepts are making steps in the right direction, but are we and is the idea enough for a modern cynical world that secretly craves either simplification or death?

Earlier generations had less knowledge and technology and worse issues to deal with, but they collectively had a hope for the future that this current society is lacking and having eroded away every day.

Wow @ljk, that may have been the most poignant, thought-provoking blog post I’ve ever read! All the proof I need was gained by reading your post this morning right after reading the election results.

We need to elect someone like ljk, or at least a Kennedy-esque charismatic who can give us hope and the direction we need to live tribe-like lives while still advancing a connected, global society in meaningful ways. Remember the scene in the asteriod/disaster flick when everyone on the planet was united and completely “one” when they saw the asteroid blow up? Talk about goose bumps! Maybe it’ll take a real global disaster (or a near-miss) to burn this into our psyche, and motivate our society to invest in our future to ensure our survival on Earth, and beyond.