I for one am astounded at the fact that it has been seven years since the launch of New Horizons. The craft, now more than halfway between the orbits of Uranus and Neptune, lifted off on January 19, 2006. I remember my frustration at having hundreds of cable channels on my television and not being able to see the New Horizons launch on any of them. I wound up tracking the event on a balky Internet transmission that, despite freezing up on more than one occasion, still got across the magic of punching this mission out into the deepest parts of the Solar System.

With the flyby at Pluto/Charon in 2015, principal investigator Alan Stern is describing what his team is feeling as ‘the seven year itch,’ a sense of anticipation feeding off the spacecraft’s continued good health along the way. Stern’s latest report is online, noting that the current ‘wake period’ of the spacecraft (New Horizons was in hibernation from July of 2012 until January 6) is proceeding smoothly, including upload of new software. New Horizons goes back to sleep on January 30 and stays under until deep into May, when summer encounter rehearsals begin. We have 903 days until Pluto closest approach.

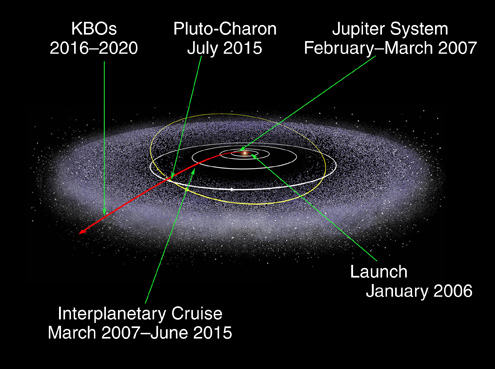

Image: The journey of New Horizons past Pluto/Charon and on into the Kuiper Belt. Credit: JHU/APL.

We should get a lot of updated information about Pluto/Charon this summer when the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory hosts a conference devoted to the distant worlds, one that will include planning for the observations that will take place during the all too brief encounter. Stern notes that the question he is most frequently asked about the mission is why New Horizons will not pull into an orbit around Pluto for extended observations, a question easily enough answered:

…getting into orbit isn’t practical because of our speed. Remember, New Horizons was the fastest spacecraft ever launched. Even after climbing uphill against the Sun’s gravity for nine years, when we reach Pluto we’ll still be going 30,000-plus miles per hour — very roughly twice the speed of a space shuttle or satellite in Earth orbit. To enter orbit around Pluto we’d need to bleed almost all of that speed off with rockets. And that would require very large rocket engines and a lot of fuel, given our fast trajectory.

Orbiting Pluto would have made for a much longer flight — decades longer — and in any case pushing on into the Kuiper Belt allows further explorations as the mission continues. This is probably the place to note that although New Horizons left Earth orbit traveling faster than any other vehicle launched into interplanetary space, its 14 kilometer per second speed at Pluto/Charon is below Voyager 1’s 17 kilometers per second-plus — as Stern says, the spacecraft has been climbing out of the gravity well for the last nine years, and slowing.

We turn to Helios II, though, for the title of fastest man-made object, although the Helios probes, launched in 1974 and 1976, were designed to study the Sun rather than to leave the system. Both were placed into highly elliptical orbits that, at closest approach, reached speeds in the range of 70 kilometers per second. It’s worth noting, too, that the upcoming Solar Probe Plus mission, also the work of JHU/APL, would actually triple Helios II’s velocity. Solar Probe Plus is designed to fly into the Sun’s corona for the first time, giving us a wealth of information about how the solar wind is accelerated. If all goes well, the mission will launch in July of 2018.

Slow boat to Centauri? Well, imagine that you could get a spacecraft up to Solar Probe Plus speeds not approaching the Sun but leaving the Solar System, no small feat. Point the craft in the direction of Centauri A and B and you’d be able to make the crossing in a bit over 6000 years. You’re making a good deal less than 1 tenth of one percent of light speed here, with an interstellar ship design that had better be either a worldship or a robotic probe designed for long-haul operations. As always, interstellar distances take the breath away as we ponder even the nearest stars.

I greatly enjoy articles that attempt to illustrate scale to readers. Time/Speed/Distance discussions concerning star travel always seem to leave people uncertain as to what the solution to the problem will be. Many lose heart and fall into the netherworld of superluminal fantasy.

I am personally fairly certain about the future of starflight- except for the strong possibility that we may go extinct in the near future. Cryopreservation is the key to traveling for centuries through space to other stars. Interestingly, the societal implications are far greater than just enabling travel to other Earth-like systems.

Once we are able to freeze people then star travel becomes possible and practical. The singular method available to humankind at present is with beam propulsion using Lunar Solar Power. By using a microwave beam projected from the surface of the Moon a starship may be accellerated out of the solar system at some fraction of the speed of light. H-bombs would be detonated in a pulse propulsion system to slow down after centuries of travel.

Science fiction has unfortunately conditioned humans to think of future starflight in terms of airline or cruise ship travel. If we adjust our worldview and think outside the “100 year lifespan box” then starflight becomes less of an impossibility and more of an engineering problem to be solved with available technology.

Paul

How fast is IIE supposed to be?

Solar probe is not bad 1/10 would be 4000 years.

You know I am broken record on this but with Les Johnson bringing it up Project Orion could get us a small probe up to 1 percent which is 400 years .

Considering we have already spent the money it would justify the small moon base a lot of people want as a launch pad…….

BTW Dish has NASA TV on 286 and Pentagon(maybe coverage of 100 year starship) on 9405 so I hope i wont miss launches.

NASA needs to do a better job of updating their schedual

The concept of “fastest man-made object” doesn’t really work in space, where speed varies along a trajectory. What would be more interesting, I think, would be the “most energetic man-made object”. This could be defined in either of two ways: the greatest delta-V imparted to a vehicle by rocket or other artificial means of thrust (including solar sail thrust), or the greatest hyperbolic excess velocity at infinity. In interstellar considerations, the latter is clearly of more direct relevance, and Voyager 1 continues to be the one to beat.

The 70 km/s of Helios II is impressive, until one remembers that this is less than parabolic velocity at that location in the Solar System: the probe does not even have enough energy to escape the Sun’s gravity, let alone any useful excess over that minimum interstellar energy.

Stephen

There is one thing I can’t help wondering about the statement “getting into orbit isn’t practical because of our speed”

Obviously the velocity difference is so great that gentle multi-pass aerobraking, as is used to circularise orbits, is only of minimal aid here to a delta V budget. But why not go all out for single pass aerobraking. Our mesosphere where all those meteorites burn up, has a density of about 2Pa, by contract the multi-pass braking of Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter never strayed lower than 95km (or so I heard) where the atmosphere should have always been <0.1Pa.

according to Wikipedia, Pluto’s maximum atmospheric density is 2.4Pa. Since Pluto has recently left perihelion shouldn’t its maximum be now, and thus single pass aerobraking possible. Also the scale height of the atmosphere is enormous at about 60km, and that must help.

On second thoughts we probably missed our window of opportunity, and need more info on this poorly understood atmosphere. A quarter of a millennium is a long time to wait!

I am curious about pr0gress toward finding the target New Horizon will aim for after the Pluto flyby. By now, they mush have found a lump of ice out there that is feasible …

Hey Ice hunters!

Paul Gilster wrote:

“Stern’s latest report is online, noting that the current ‘wake period’ of the spacecraft…”

Please don’t jinx New Horizons by saying “wake!” “*Awake* period” is the safe term to use. :-) To assuage our burning anticipation for its closest approach to Pluto (‘perihades?’), we can think of the nuclear rocket-powered asteroid Fabrini generation ship Unada, from the Star Trek episode “For the World is Hollow and I Have Touched the Sky,” which was also 900-and-change days from its destination world when the Enterprise encountered it. We can say to ourselves–as Unada’s oracle told the people–“Soon” whenever we think of the upcoming Pluto flyby. :-)

James Jason Wentworth, you are worried about Paul using the word “wake” yet you ask us to compare the Pluto mission to a worldship that was going to smash into an inhabited planet?! How is this better? :^)

Have we any additional data on any more possible moons in orbit around Pluto or perhaps dust rings any of which might cause problems. If we don’t know well in advance by the time Horizon does its fly by it might be to late to make adjustments and the craft could be in trouble.

IIRC it’s been said here before that a “sundiver” probe might be faster way to get to interstellar space than the IIE. I’m interested in this mainly for the selfish reason that even if the IIE had launched in 2014 I would have been 88 when it reached it’s targeted 200 a.u. from the sun in 2044. Since the next launch window for an IIE mission is 2026 I’d literally have to live to be a hundred to see the end of it. So if something can get out there quicker (even if we have to take more time to develop it) I’m all for it.

RON MILLER

Yesterday 11:00am

How I Helped Get Us To Pluto

Back in 1991 I did a series of illustrations for a set of US commemorative postage stamps, one for each planet and the Moon. There was a spacecraft associated with each world . . . except Pluto. And there was something about that stamp that rankled a lot of scientists.

In 1993 JPL engineer Robert Staehl explained what the problem was in a paper titled, “To Pluto from a First-Class Postage Stamp.” “During 1991,” he wrote, “with Voyager 2’s Neptune encounter two years behind us, the U.S. Postal Service issued ten stamps commemorating the success of planetary exploration.

On a stamp for each of the first eight planets and the Moon appeared an illustration of the celestial body with one of the spacecraft which visited it. The stamp for Pluto simply announced, NOT YET EXPLORED, as if to taunt engineers and scientists at Pasadena’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) , where the stamp were unveiled in a first-day-of-issue ceremony on October 1 . . .”

On that same day Staehl stopped by the office of his friend Stacy Weinstein, of JPL’s Advanced Projects Group, with the Pluto stamp. Staehl “jokingly asked what we were doing about this travesty of ‘Pluto – Not Yet Explored.’”

That was when “the mission was born,” Staehl concluded. A team of scientists and engineers at JPL, led by Staehl, was the first to seriously propose a mission to the distant world. This became the Pluto Fast Flyby mission which eventually evolved into the ambitious Pluto-Kuiper Express.

http://io9.com/how-i-helped-get-us-to-pluto-453895132