What we hope to learn from early experiments with the electric sail is whether keeping a steady electric potential on long tethers will give us enough interaction with the solar wind to make for viable propulsion. ESTCube-1, launched earlier this week, is a step in that direction. Even though it uses but a single 10-meter wire, its rotation rate should change once the tether is fully extended and powered up. Bear in mind that ESTCube-1 is deep within the Earth’s magnetosphere, so the charged particles it will be interacting with are not from the solar wind, but a proof of principle is sought here that could make electric sailing a candidate for outer system-bound spacecraft.

It’s important to distinguish between solar sails and their electric counterparts. The Japanese IKAROS sail, successfully tested, showed that solar photons could impart momentum to a thin sail, as our experience with early satellites had already demonstrated. The beauty of sailing in any form is that we leave the propellant behind. The biggest problem with the rocket equation is that it tells us that as speed increases linearly, propellant mass increases exponentially. That’s why chemical rockets can’t take us to the stars, and why finding a way around carrying propellant has inspired concepts from lightsails to ramscoops and forms of pellet propulsion.

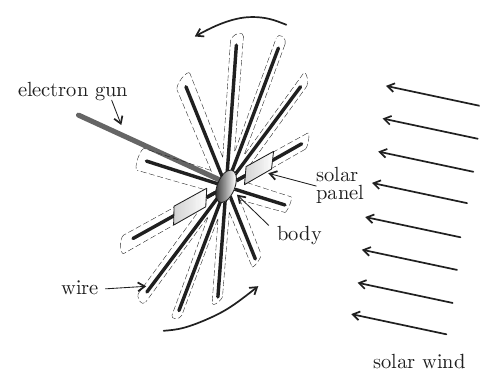

Pekka Janhunen’s work suggests that a fully developed electric sail might deploy 100 tethers by using its rotational motion, while an electron gun with beam sent along the spin axis would power up the system. In a sense, then, the electric sail does use electric power as part of producing thrust — in this way it’s similar to an ion engine. And in the sense that it hitches a ride on the solar wind, it could also be compared to the magnetic sail, which grew out of work by Dana Andrews and Robert Zubrin on creating a magnetic scoop to collect interstellar hydrogen. The magnetic scoop turned out to create more drag than the engine it fed could overcome, at which point the idea of using a magnetic sail for deceleration came into the picture.

An electric sail rides the solar wind using different principles, depending upon Coulomb interaction — the attraction or repulsion of particles caused by the electric charge — with the solar wind to get the work done. Positively charged solar wind protons are repelled by the positive voltage they encounter in the charged tethers. At the same time, captured electrons are ejected by an onboard electron emitter to avoid neutralizing the charge built up in the tether system.

Image: A full-scale electric sail consists of a number (50-100) of long (e.g., 20 km), thin (e.g., 25 microns) conducting tethers (wires). The spacecraft contains a solar-powered electron gun (typical power a few hundred watts) which is used to keep the spacecraft and the wires in a high (typically 20 kV) positive potential. The electric field of the wires extends a few tens of metres into the surrounding solar wind plasma. Therefore the solar wind ions “see” the wires as rather thick, about 100 m wide obstacles. A technical concept exists for deploying (opening) the wires in a relatively simple way and guiding or “flying” the resulting spacecraft electrically. Credit: Pekka Janhunen.

What worries some scientists about schemes that use the solar wind, though, is its variability. We’re dealing with a continuous stream of plasma flowing outward from the Sun. While a solar sail works with a steady source of photons, an electric sail will have to contend with solar wind particles that can vary between 400 and 800 kilometers per second. In their book Solar Sails: A Novel Approach to Interplanetary Travel, Gregory Matloff, Les Johnson and Giovanni Vulpetti compared riding the solar wind to putting a message into a bottle at high tide and throwing it out to see whether the currents will take it to the right destination.

But here the electric sail design may have an edge on magnetic concepts, because the spacecraft may be able to control the electric field that surrounds it. Would this be sufficient to produce a controlled level of thrust despite a rapidly shifting solar wind flowing past the vehicle? The question is unanswered, which is why we need early experiments like ESTCube-1 and the upcoming Aalto-1 to tell us more. But as he is the authority on electric sails, it seems pertinent to quote Pekka Janhunen on the matter. He believes that the thrust can be controlled by adjusting the electron gun current or voltage. This is from a 2009 paper delivered at the Aosta interstellar conference in Italy:

…there are two mechanisms that efficiently damp the variations of the electric sail thrust even when the solar wind parameters (density and speed) vary a lot. The first mechanism is due to the fact that the electron sheath width has an inverse square root dependence on the solar wind electron density. Thus when the solar wind density drops, the thrust becomes lower because the dynamic pressure decreases, but the simultaneous increase of the effect sail area (sheath width) partly compensates for the decrease.

So in at least one sense we have the possibility of a self-correcting system. Janhunen goes on:

The second mechanism arises from the natural desire to run the electric sail electron gun with the maximum available power. When the solar wind electron density drops, so does the electron current gathered by the tethers, so that one may increase the tether voltage (electron gun voltage) without increasing the power consumption. Both mechanisms combined imply that if applying the strategy of running the electric sail with the maximum available power, the thrust depends only on power ? of the solar wind density.

Janhunen goes on to say that the navigability of the electric sail is “almost as good as that of any other propulsion system such as an ion engine.” His results so far have shown that variations in the thrust are much weaker than variations in the solar wind itself, and careful juggling of power margins should allow the craft to correct for the unevenness of the flow. All this, of course, needs to be tested out in space, and not just through small, preliminary satellites but larger deployments that build upon what we learn. It’s good to see with the launch of ESTCube-1 that this process has begun.

The paper is Janhunen, “Status report of the Electric Sail: a revolutionary near term propulsion technique in the solar system,” in Proceedings of the 6th IAA Symposium on Realistic Near-Term Advanced Scientific Space Missions: Missions to the outer solar system and beyond, G. Genta (ed.), Aosta, Italy, 6-9 July 2009, 49-54, 2009.

Would you try to ride the helio-electric current with an electric sail?

What about the wires made from a superconductor? It quite possible to use a superconductor in the outer reaches of a solar system, when temperature will fall close to cryogenic.

For a propulsion purpose, the high frequency and impulsive, positive electric field applied to the wires will be much more effective than a constant electric field. Why? Protons will be possible to direct in the OPPOSITE course by applying high positive potential in a moment when protons fly a close to a wires. Propelling the protons backward to the Sun, in such way as it going on in an ion thruster and using them like a reactive body (a fuel). Of course, frequency of an electric field must be a variable and dependable from Sun’s wind speed.

Excuse me for my English. I’m from Ukraine.

So how would you tack such a sail so that you could go from say Jupiter to Earth? If you can’t then you can only do outbound missions. Which is fine if you just want to send a probe outward from earth but what about a sample return mission?

Stanley, this is from Pekka Janhunen’s website on the concept:

AlfaCentavra may be on to something important when he proposes a super conducting high frequency electric field propelling a reactive thrust which might assist brake parameters after interstellar flights. It always pleases when Centauri Dreams stimulates ideas and discussions which may lead to future innovation in space technology.

This seems to me to be an extremely interesting direction for research. Probably not for manned flight so much as for filling the solar system with probes of all kinds. I am very much interested in probes. Smaller, smarter, better, cheaper, lighter, faster. The more probes the better. This technology looks very promising on that front.

Excellent, being able to ‘sail’ a spacecraft powered by this method both out bound and inbound opens up the possibility of sending out a probe to drop off a survey package and then returning to earth orbit and collect yet another package for delivery to another location. One such craft could be used multiple time thus decreasing the cost enormously.

The protons are already ejected in the opposite direction with the design. But if you want increase the repelling, you need to use energy, but why not. I don’t really understand the high frequency concept proposed. You mean if you make a high frequency field, some protons could come closer to the wire and then be repelled faster when the field is turned higher than the field average? What about distant protons which are slowed just slightly by the higher electric field to the point they just stop and never experience a push back? There is a force called ponderomotive force that could be linked, is this what you are talking about? In that case, it repels both negative and positive charges, which is good. Calculations might not be very hard, but you have to consider the incoming flow of positive charges and their variation with the varying density induced by the high frequency repelling…well that might be hard calculations.

In the same spirit one can argue that a deceleration device is also an acceleration device in another reference frame, so both electric and magnetic sail could be used to accelerate as long as one propel it in the other direction. Pushing the sail itself could increase the flow of electric charges, and the speed of repelling but that is costly both in energy and hardware. Of course with electric devices, one can push virtually, without ejecting all the stuff.

I thought during my studies, looking about Faraday cage and charged sphere, that you could use charged sphere to shield a spaceship like a magnetosphere, without experiencing any field into the ship. Put one large sphere of negative charges, then, put one sphere of positive charges into the first negative sphere. outside the two sphere, there is no field between the two there is a “positive” field (outward), and inside there is no field again. now if positive charges come they will be repelled by the positive field around the ship. The negatives charges will be accelerated inward the ship… But the you can make the very same system still outside the ship, but inside the two previous sphere, reversing positive and negative charge in order to obtain a negative field. You have to make the field at least twice as strong than the first, and then the negative charges will be repelled outside the 4 spheres at the same velocity they came. Is that clear?

I think that Stanley has hit on the key facet for the future of Interplanetary flight /exploration/exploitation : reducing costs for “propulsion”. This would have to be a consideration as the size/weight/mass of unmanned and manned payloads increase.

Perhaps numerous such craft could orbit the sun judging whether there is a serendipitous alignment between the solar wind speed and alignment with a target. If so, then it unfurls it’s wires, charges up and rides the wind in the approximate direction of the target. It adjusts its charge and, as it nears the speed of the wind it waits until its trajectory just so happens to be about right and then disconnects its wires in order to continue on its present trajectory.

If it were able to fully catch the speed of the solar wind at its max (800 km/sec) then it would arrive at Alpha Centauri in about 1,745 years. Too long for a science probe but potentially good for an ESCAPE Mission.