How do you close on a comet? Very carefully, as the Rosetta spacecraft has periodically reminded us ever since late January, when it was awakened from hibernation and its various instruments reactivated in preparation for operations at comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. The spacecraft carried out ten orbital correction maneuvers between May and early August as its velocity with respect to the comet was reduced from 775 meters per second down to 1 m/s, which is about as fast as I was moving moments ago on my just completed morning walk.

What a mission this is. When I wrote about the January de-hibernation procedures (see Waking Up Rosetta), I focused on two things of particular interest to the interstellar-minded. Rosetta’s Philae lander will attempt a landing on the comet this November even as the primary spacecraft, now orbiting 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, continues its operations. We’re going to see the landscape of a comet as if we were standing on it, giving Hollywood special effects people legions of new ideas and scientists a chance to sample an ancient piece of the Solar System.

You’ll want to bookmark the Rosetta Blog to keep up. But keep in mind the other piece of the puzzle for future space operations. Rosetta will be looking closely at the interactions between the solar wind — that stream of charged particles constantly flowing from the Sun — and cometary gases. We’ll learn a great deal about the composition of the particles in the solar wind and probably get new insights into solar storms.

Remember that this ‘solar wind’ isn’t what drives the typical solar sail, which gets its kick from the momentum imparted by solar photons. But there are other kinds of sail. The Finnish researcher Pekka Janhunen has discussed electric sail possibilities, craft that might use the charged particles of the solar wind instead of photons to reach speeds of 100 kilometers per second (by contrast, Voyager 1 is moving at about 17 km/s). Rosetta results may help us understand how feasible this concept is.

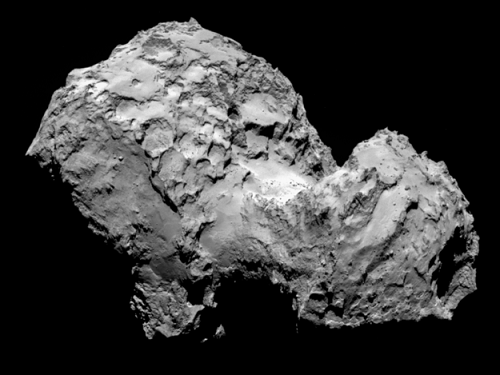

Image: Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko by Rosetta’s OSIRIS narrow-angle camera on 3 August from a distance of 285 km. The image resolution is 5.3 metres/pixel. Credit & Copyright: ESA / Rosetta / MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS / UPD / LAM /IAA / SSO / INTA / UPM / DASP / IDA.

That image is a stunner, no? Now that Rosetta has rendezvoused with 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, we can think back not only to the orbital correction maneuvers but the three gravity assist flybys of the Earth and one assist at Mars, allowing a trajectory that produced data about asteroids Steins and Lutetia along the way. It’s been a long haul since 2004 and you can see why Jean-Jacques Dordain, the European Space Agency’s director general, is delighted:

“After ten years, five months and four days travelling towards our destination, looping around the Sun five times and clocking up 6.4 billion kilometres, we are delighted to announce finally ‘we are here.’ Europe’s Rosetta is now the first spacecraft in history to rendezvous with a comet, a major highlight in exploring our origins. Discoveries can start.”

Getting the hang of operations around the comet is going to be a fascinating process to watch. Right now the spacecraft is approximately 100 kilometers from the comet’s surface, and over the course of the coming six weeks, while close-up studies from its instrument suite proceed, it will nudge closer, down to 50 kilometers, and eventually closer still depending on comet activity. Remember that images from the OSIRIS camera showed a dramatic variation in activity between late April and early June as the comet’s gas and dust envelope — its ‘coma’ — brightened and then dimmed within the course of six weeks. These are quirky, lively objects, and we now proceed to teach ourselves the art of flying a spacecraft near them for extended periods.

This ESA news release tells us that the plan is to identify five landing sites by late August, with the primary site being chosen in mid-September. The landing is currently planned for November 11, after which we’ll have both lander and orbiter in operation at the comet until its closest solar approach in August of 2015. Comets are ancient pieces of the Solar System that may well have delivered the bulk of Earth’s oceans. Now we’ll see up close what happens to a comet as it approaches the Sun. Congratulations and Champagne are due all around for the planners, designers, builders and controllers of this extraordinary mission. Onward to the surface.

its surface temperature is very interesting

Darn if that thing doesen’t look like a space alien right out of the TV show “Face Off”(two short close-together stubby legs, no arms, a head almost as big as the body, and a RADULA for a mouth). BUT: on a more serious note, here’s an UPDATE on az 2010 post about PSR J1928+15. The “beacon-like” pulses may not have originated from an asteroid falling on the pulsar, but, INSTEAD, a small asteroit TRANSITING it (or a large asteroid or planet OCCULTING it. This is apparently due to “Alfven wings and other stuff that is way beyond me. The bottom line i, if THIS IS THE CASE, the signals should REPEAT! Check out today’s Exoplanet Encyclopedia’s bibliography for details.

If the “duck shape” is due to erosion by out gassing, it may be a more advanced state than the peanut shape we’ve seen in the past, e.g. Comet 103P/Hartley.

In many respects, I find this mission more interesting that the proposed asteroid capture and crewed rendezvous in cis-lunar space. Some very interesting science at a fraction of the cost of an ARM mission. If New Horizons ever manages a KBO flyby, will will have an example of a pristine “dirty snowball” to compare this to.

I too hope that Hollywood (and space artists) use the imagery from this rendezvous to re-imagine what the surface of a comet should be like.

we should land at the neck of this putative contact binary so that we can receive images looking up at both lobes

‘Nothing So Hidden’: ESA’s Rosetta Meets its Target Comet after Decade-Long Journey

By Emily Carney

Astronaut and Apollo 16 moonwalker John Young was once quoted as saying, “[René] Descartes…said, ‘There’s nothing so far removed from us as to be beyond our reach, or so hidden that we cannot discover it.’” Well, it appears that Mr. Descartes and Captain Young were right.

On the second anniversary of NASA’s Curiosity rover landing on Mars, earlier today the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Rosetta spacecraft rendezvoused with comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko following a journey a decade in the making.

The spacecraft and comet are both now approximately 405 million kilometers (252 million miles) away from Earth between the orbits of Jupiter and Mars in what is the first ever “meet up” of its kind. Rosetta and its lander, Philae, will accompany the comet on its journey around the Sun during the next year through the end of its science mission in December 2015.

Jean-Jacques Dordain, ESA’s Director General, conveyed his excitement over the space agency’s historic milestone. “After ten years, five months and four days traveling towards our destination, looping around the Sun five times and clocking up 6.4 billion kilometers, we are delighted to announce finally, ‘we are here.’ Europe’s Rosetta is now the first spacecraft in history to rendezvous with a comet, a major highlight in exploring our origins. Discoveries can start.”

Full article here:

http://www.americaspace.com/?p=65617

Very interesting degradation pattern on the comet.

Would this type of pattern infer that the material in said comet

is not uniform. Could it indicate it is a fragment of a larger

ice body where differentiation of materials due Gravitational

gradient would leave stratified layers with different reactions to

solar heating.

Truly most incredible thing to me about the entire cometary surface is that the left-hand portion of the picture looks like there was some type of melting and flow down the surface of the body of the comet. Damned if it ain’t the most unusual looking surface that I’ve ever seen on a another extraterrestrial body!

Dear Paul,

The whole story of Rosetta brings up an issue that was long on my mind. Apparently one of the gravitational slingshots (Mars) of Rosetta was not to gain momentum but to slow down. Could we use the same principle for interstellar mission? Could we, for example, send a probe to Alpha Centauri B and use gravity of Proxima to slow down the spacecraft? Haven’t seen anywhere a discussion of such an option.

The way I see it is that two or three bodies have come together slowly with the impact causing the material to flow towards the neck of the newly formed body. As mentioned earlier if the landing site is on the neck of the comet I wonder if the communication beam could be used to probe the material as it is intercepted on its way to Earth. I am not alone in believing we are going to get striking science from this encounter.

@william August 7, 2014 at 15:39

‘Damned if it ain’t the most unusual looking surface that I’ve ever seen on a another extraterrestrial body!’

Try Hyperion around Saturn, that is just weird!

Rafal writes:

I believe Icarus looked at this — I think it was Adam Crowl who did the work — and concluded that using Proxima as a flyby wasn’t practical. But I don’t have the details, and because Adam is a frequent commenter here, I’m hoping he’ll chime in.

Remembering Dr. Comet

Posted on August 8, 2014 by Patrick McCray

I really wish Fred Whipple was still alive to read the papers this week. There, amidst the Middle East horribleness, he would have read about how the space probe Rosetta is nearing the comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

As of this morning, the craft had pulled to within 60 miles of 67P’s surface. Both are traveling about 35,000 miles per hour – that’s 35 miles a second (!) – in a compact duet. And, if all goes to plan, Rosetta will soon jettison a dishwasher-sized box called Philae which will land on the comet and analyze it.1

Full article here:

http://www.patrickmccray.com/2014/08/08/remembering-dr-comet/

Jim Bell of the Mars Exploration Rovers fame with his take on what Rosetta and Philae will find at Comet 67P:

http://www.cnn.com/2014/08/08/opinion/bell-rosetta-comet/index.html?hpt=hp_t3

To quote:

Editor’s note: Jim Bell is an astronomer and planetary scientist in the School of Earth and Space Exploration at Arizona State University. He is president of The Planetary Society and author of “Postcards from Mars,” “The Space Book” and most recently, “The Interstellar Age,” due out in early 2015. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.

(CNN) — More than 200 years ago, part of a stone tablet was discovered in Egypt that provided the first reliable way to translate ancient hieroglyphics into a modern language. The Rosetta Stone, as the tablet is called, proved to be the key to unlocking details of the rise and fall of civilizations that flourished on our planet many thousands of years ago.

More recently, a space mission bearing the name Rosetta has begun its quest of unlocking details of the rise and fall of entire planets, including the only one we know that is a safe haven for life.

The European Space Agency’s Rosetta mission is a robotic spacecraft designed to get up close and personal with the nucleus of a comet. The comet is called 67P/C-G (short for Churyumov–Gerasimenko, the astrophysicists who discovered it in 1969), and it orbits the sun on a 6½ year elliptical path that takes it from just beyond the orbit of Jupiter to just outside the orbit of Earth.

Date: 21 Feb 2007

Scientific Planning and Commanding of the Rosetta Payload

D. Koschny, V. Dhiri, K. Wirth, J. Zender, R. Solaz, R. Hoofs, R. Laureijs, T.-M Ho, B. Davidsson, G. Schwehm

Paper online here:

http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11214-006-9129-3

Even closer image. Very interesting surface. http://www.esa.int/spaceinimages/Images/2014/08/Comet_details

@Rafal

‘..Could we, for example, send a probe to Alpha Centauri B and use gravity of Proxima to slow down the spacecraft? Haven’t seen anywhere a discussion of such an option.’

A very close flyby of Proxima Centauri (it is very cool) to change the direction and a magnetic sail been used as a drag chute could be doable, it would slow the craft by interacting with the stars solar wind and powerful magnetic fields. Think of a thin elastic band of conducting wire traveling behind the craft, as the magnetic field of the star cuts the wire a current will flow dissipating energy as heat, by changing the conductance state of the wire we can control the magnetic fields size and braking power.

I’ve read that comets like Halley are coal black and covered with a kind of tar. Why is this one so different? i wanted to see primordial goo.

This one looks like a giant flint knapper’s work in progress :)

Rafal, Paul, Michael,

It depends on what kind of travel time you are aiming for. If tens of thousands of years is fast enough, yes, then gravitational, magnetic or electrostatic forces could act usefully on the spacecraft. At near-relativistic speed, on the other hand, the craft would whiz by Proxima (or any star) so quickly that any effect on it’s course or velocity would be negligible.

Here are images of all the comets visited and photographed close up by space probes so far:

http://planetary.s3.amazonaws.com/assets/images/9-small-bodies/2014/20140804_comets_sc_0-000-020_2014_2.png

The question is, why is it that of the six comets, four of them are dumbbell shaped? Is that a more common form for comets?

If you want an unusual celestial surface from the other extreme, we should be sending a probe to this moon of Saturn, Methone. It looks like an egg.

http://www.newscientist.com/article/dn23560-astrophile-saturns-egg-moon-methone-is-made-of-fluff.html#.U-fUy_ldUWI

Some Of Comet ISON’s Organic Materials Arose In An Unexpected Place

by ELIZABETH HOWELL on AUGUST 12, 2014

While Comet ISON’s breakup around Thanksgiving last year disappointed many amateur observers, its flight through the inner solar system beforehand showed scientists something neat: it was carrying organic materials with it.

A group examined the molecules surrounding the comet in its coma (atmosphere) and, along with observations of Comet Lemmon, created a 3-D model that you can see above. Among other results, this revealed the presence of formaldehyde and HNC (hydrogen, nitrogen and carbon). The formaldehyde was expected, but the spot where HNC was found came as a surprise.

Scientists used to think that HNC is produced from the nucleus, but the research revealed that it actually happens when larger molecules or organic dust breaks down in the coma.

“Understanding organic dust is important, because such materials are more resistant to destruction during atmospheric entry, and some could have been delivered intact to early Earth, thereby fueling the emergence of life,” stated Michael Mumma, a co-author on the study who is director of the Goddard Center for Astrobiology. “These observations open a new window on this poorly known component of cometary organics.”

Full article here:

http://www.universetoday.com/113856/some-of-comet-isons-organic-materials-arose-in-an-unexpected-place/

Alice in Comet-Land: NASA Instrument Aboard Rosetta Returns First Scientific Results

By Emily Carney

NASA announced that one of its three instruments aboard Rosetta, the European Space Agency (ESA) spacecraft currently orbiting comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, has successfully delivered its first set of science results back to Earth. Alice, an ultraviolet spectrometer, has revealed yet more unexpected findings about the comet, which Rosetta rendezvoused with in early August after a decade-long journey.

NASA revealed that Alice has shown the comet to be “unusually dark”—described as “darker than charcoal-black”—in ultraviolet light wavelengths. The instrument also revealed that the comet’s tail, or “coma,” contains hydrogen and oxygen, and the comet possesses no visible large ice patches.

The latter finding is surprising, given the comet is quite some distance away from the Sun; patches of ice were expected to be found un-melted. Alan Stern, who is the Alice principal investigator at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo., discussed these findings, underscoring their unanticipated nature.

“We’re a bit surprised at just how un-reflective the comet’s surface is, and how little evidence of exposed water-ice it shows,” Stern related.

Alice is one of two instruments aboard Rosetta fully funded by the United States’ space agency, and is meant to analyze the comet’s composition in a manner not possible from Earth or remote sites. According to a previous AmericaSpace article published in June, other instruments provided by NASA aboard Rosetta include the Microwave Instrument for Rosetta (MIRO) and the Ion and Electron Sensor (IES). The article stated that MIRO “will provide data about the evolution of the comet’s tail and ‘coma’ (the area around the comet’s nucleus), shedding light upon how this section of the comet develops as it approaches and departs our nearest star, the Sun.”

According to NASA, IES “is part of a suite of five instruments to analyze the plasma environment of the comet, particularly the coma.” NASA also helped to design a part of the Double Focusing Mass Spectrometer (DFMS) electronics package for the Rosetta Orbiter Spectrometer for Ion Neutral Analysis (ROSINA), which was mainly fabricated in Switzerland. In total, Rosetta carries 11 science instruments, as well as a lander, Philae.

Full article here:

http://www.americaspace.com/?p=67080

Rosetta Update: Spacecraft Takes ‘Selfie’ by Comet as Team Determines Landing Site

By Emily Carney

You may have taken a selfie before, but not one quite as cool as this: This week in Rosetta news, the European Space Agency’s (ESA) comet-orbiting spacecraft took an incredible “selfie” of sorts at comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko.

ESA released an image taken Sunday, Sept. 7, at a distance of approximately 50 kilometers (31 miles) from the comet. The viewer can observe one of Rosetta’s silvery solar wings, with the distinctive double-lobed comet lurking in the background. ESA stated that this image was the result of combining “two images with different exposure times … to bring out the faint details in this very high contrast situation.” More recent images from Rosetta via ESA are featured at the end of this update.

Full article and amazing images here:

http://www.americaspace.com/?p=67392

Landing Site Selected for First-Ever Attempt to Land on a Comet

By Paul Scott Anderson

A landing site has now been chosen for the Rosetta spacecraft’s lander, Philae, on comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko, it was announced this morning. After several candidate landing sites had been considered, site J has now been selected for the daring landing later in November. It will be the first-ever attempt to actually land on a comet.

“As we have seen from recent close-up images, the comet is a beautiful but dramatic world – it is scientifically exciting, but its shape makes it operationally challenging,” said Stephan Ulamec, Philae Lander Manager at the DLR German Aerospace Center. He added, “None of the candidate landing sites met all of the operational criteria at the 100% level, but Site J is clearly the best solution.”

Full article here:

http://www.americaspace.com/?p=67544

To quote:

“No one has ever attempted to land on a comet before, so it is a real challenge,” said Fred Jansen, ESA Rosetta mission manager. “The complicated ‘double’ structure of the comet has had a considerable impact on the overall risks related to landing, but they are risks worth taking to have the chance of making the first ever soft landing on a comet.”

There is a backup landing site, C, which also has adequate illumination from the Sun and few boulders, in the event that site J is no longer viable for some reason. A detailed operational timeline must now be prepared by the Rosetta team, in order to determine the specific trajectory the lander will take as it descends.

The landing must take place before mid-November because after that, the comet will start to become too active with its jets of water vapor and ice spewing out from the surface as it approaches closer to the Sun. Some activity has already been observed by Rosetta, with faint plumes emanating from the “neck” region of the comet.

LJK – I still think they should have tried landing as near as they could to where the two lobes of the comet meet. If this was the result of two comets merging with each other, they could have sampled two such bodies for the price of one, as it were. But hey, I’m no comet landing rocket scientist.

All That is Known About Bennu

Posted by Dante Lauretta

2014/09/24 16:01 UTC

Topics: asteroids, OSIRIS-REx, explaining science

This article originally appeared on Dante Lauretta’s blog and is reposted here with his permission.

Today, we released the OSIRIS-REx Design Reference Asteroid (DRA) document to the public. The DRA is a compilation of all that is known about the OSIRIS-REx mission target, asteroid (101955) Bennu. We are making this document available as a service to future mission planners in the hope that it will inform their efforts.

Full article here:

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/guest-blogs/dante-lauretta/20140917-all-that-is-known-about-bennu.html

The document online here:

http://arxiv.org/abs/1409.4704

http://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1409/1409.4704.pdf

Philae’s landing day announced as Rosetta swings to comet’s dark side

Posted By Emily Lakdawalla

2014/09/26 20:36 UTC

Topics: Rosetta and Philae, pretty pictures, comets, amateur image processing, mission status, comet Churyumov-Gerasimenko

ESA announced today that Philae will be landing on November 12, 2014. What time the landing occurs depends on which landing site they use. If they go to the prime landing site, “site J,” Earth should receive word of the successful landing at 16:00 UTC (08:00 PST). If they go to the backup site, “site C,” news will reach Earth at about 17:30 UTC (09:30 PST). Mark your calendars! The final choice of landing site will happen on October 14. Here is a little more detail on the timing of landing for different sites:

Full article here:

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/emily-lakdawalla/2014/09261328-philaes-landing-day.html

MISSION SELFIE FROM 16 KM

If you thought last month’s mission ‘selfie’ from a distance of 50 km from Comet 67P/C-G was impressive, then prepare to be wowed some more: this one was taken from less than half that distance, at just 18 km from the centre of the comet, or about 16 km from the surface.

http://blogs.esa.int/rosetta/2014/10/14/mission-selfie-from-16-km/

Philae Detects Organic Molecules at Comet Landing Site

By Ken Kremer

Europe’s intrepid and plucky Philae spacecraft has detected organic molecules on the surface of a comet after successfully completing history’s first ever soft landing on a comet and subsequently surviving two harrowingly unplanned bounces before finally coming to rest, barely a week ago.

Since organics are the building blocks of life, their in situ discovery marks a breathtaking achievement for the history making mission of the Rosetta orbiter and Philae lander to investigate comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko.

The European Space Agancy’s (ESA) Philae robotic probe touched down safely on the dust covered icy surface of the distant comet in a heavily shadowed spot beside a cliff on Nov. 12, after a gutsy 10 year interplanetary trek through space while traveling some 500 million kilometers (300 million miles) from Earth on a mission of cutting edge science to elucidate our origins.

The science team leading the Philae probe confirmed the discovery of organics in a statement from the DLR (Deutsche Luft und Raumfahrt or German Space Agency), which heads the consortium funding the lander.

Full article here:

http://www.americaspace.com/?p=71563

I was told that the Rosetta team did NOT test the harpoon system on Philae in a vacuum and only learned this September (!) that the harpoons would not work in a vacuum. I have been trying to learn more but so far nothing.

I did get one “answer” via The Planetary Society’s Facebook page that the ice surface of Comet 67P is too hard and the harpoons would not have penetrated the surface anyway, but that just avoids answering my actual question.

Why wouldn’t the Rosetta team test something so critical while the probe was still on Earth? They came darn close to losing Philae completely as a result and even then the little lander could have been returning data for months had it not landed in such a tough and dark area. Imagine if we could have been monitoring surface conditions on a comet as it nears Sol.