With the question of habitable planets on my mind following Andrew LePage’s splendid treatment of Kepler-452b on Friday, I want to turn to the interesting news out of San Diego State, where astronomer William Welsh and colleagues have been analyzing a new transiting circumbinary planet, a find that brings us up to a total of ten such worlds. Planets like these, invariably likened to the planet Tatooine from Star Wars, have two suns in their sky. Now we have Kepler-453b to study, a world that presented researchers with a host of problems.

Transits of the new world occur only nine percent of the time because of changes in the planet’s orbit. Precession — the change in orientation of the planet’s orbital plane — meant that Kepler couldn’t see the planet at the beginning of its mission, but could after it swung into view about halfway through the mission’s lifetime, allowing three transits. Clearly, this is a system we could easily have missed, says William Welsh (San Diego State), who was lead author on the study. Welsh calls the find ‘a lucky catch,’ and it’s hard to argue: The precession period is estimated to be about 103 years, with the next set of transits not becoming visible until 2066.

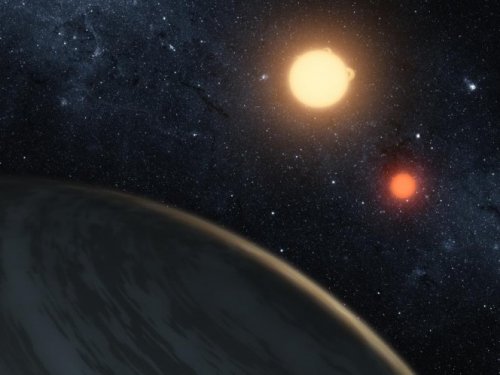

Image: An artist’s impression of the circumbinary extrasolar planet Kepler-453b. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/T Pyle.

It was Welsh, working with San Diego State colleague Jerome Orosz, who used Kepler data back in 2012 to discover the first instance of a two-planet circumbinary system, one of the two worlds being in the habitable zone where liquid water could exist on a solid surface. Kepler-453b turns out to be the third planet identified by the mission as being a circumbinary world in the combined habitable zone of two stars. The world is a gas giant, however, and unlikely to host life as we know it (life as we don’t know it is another matter, but that’s true in our own Solar System as well).

What we’re able to deduce about Kepler-453b so far is that it has a radius about six times that of the Earth, and a mass — not readily measurable with current data — probably less than 16 times that of Earth. The planet’s orbit is 240 days, and the two stars it orbits orbit each other every 27 days. The larger star in much like our own, with 94 percent the mass of the Sun, while the smaller is about 20 percent as massive and much cooler. The Kepler-453 system is 1400 light years away in the constellation Lyra, a young system probably between one and two billion years old.

So are we going to find an Earth-like planet in a circumbinary orbit one of these days? What we’ve learned thus far is that circumbinary planets are not unusual — we’ve already found ten — and the range of configurations is wide. An Earth-class planet in the habitable zone of one of these stars would conjure up those wonderful images of twin stars at sunset, one of them going down before the other, a world of intriguing hues and shadows as the two stars moved through their own orbits, with occasional eclipses thrown in for good measure. Circumbinaries are another reminder of the diversity we’re coming to expect as we build the exoplanet catalog.

The paper is Welsh et al., “Kepler 453 b—The 10th Kepler Transiting Circumbinary Planet,” Astrophysical Journal 5 August 2015 (abstract). An SDSU news release is available.

A gas giant in the habitable zone could be just as interesting as an earth sized planet in that zone, depending on whether it has moons or not. What if a gas giant in the habitable zone of a binary system had one or more mars size or bigger, habitable moons? How interesting would that system be?! Imagine the sunsets/rises/eclipses in such a system. It’s frustrating that we don’t have the instruments to find such moons yet, but hope it happens soon.

@Ross Turner August 10, 2015 at 16:21

‘A gas giant in the habitable zone could be just as interesting as an earth sized planet in that zone, depending on whether it has moons or not… ‘

Gas giants with their powerful magnetic fields accelerating charges can be quite dangerous places to be.

I know that this is a LITTLE BIT off topic, but I just read an intreguing abstract(which was so technically above my understanding of this matter, that I did NOT click on “PDF” and read the entire paper). The overall gist of the abstract was:A BETTER data retreval method than the currently used Kepler PDC(Pre-search Data Conditioning). It is called “CPM”, or Causal Pixel Model. Its advantage over PDC is that it can MODEL ‘jitter” and OTHER FACTORS that CURRENTLY PREVENT a transit signal from being EXTRACTED from the overall noise. Just from the abstract, I can reasonably assume that, if this new method IS as good as it is touted to be, applying it to EVERY PIXEL in the main mission dataset(I don’ know whether this even APPLIES to K2) could take DECADES with the CURRENT computer technology available (Moore’s Law should help out here, I hope) for the HIGH-CADENCE data, and several years for the low cadence data. The bottom line is, we may be able to detect MANY MORE TRULY EARTH SIZED PLANETS in the habitable zones of G and LATE F stars, and even a FEW sub-earths in their habitable zones as well. I urge Any reader with more expertise than me in this field (Andrew LePage et al) to read the entire paper and report back.

@Michael August 11, 2015 at 3:33

True, the radiation environment around gas giants can present issues but a magnetic field even around a moon not much larger than Mars is sufficient protect its atmosphere from erosion making it potentially habitable. In addition, gentle tidal heating and other effects could allow such a small world to maintain a magnetic field far longer than it would in isolation. These and other issues surrounding habitable moons are detailed in a Sky & Telescope article I wrote many years ago that is still available on-line:

http://www.skyandtelescope.com/astronomy-news/habitable-moons/

A more recent review of the topic (along with a link to a fully referenced review paper) can be found in an essay I wrote more recently for Centauri Dreams, “Habitable Moons: Background and Prospects”:

https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=31557

Interestingly enough, the ninth transiting circumbinary planet from the Kepler mission is the still-to-be-announced third planet of Kepler-47.

More breaking Kepler news: K2 has detecetd a 55Cancri analog, but even MORE extreme! WASP 47c has almost the EXACT SAME PARAMETERS as 55 Cancri e, but instead of a warm jupiter with a 14 day orbital period as the next planet out, WASP 47b is a HOT jupiter with only a 4 day period! In terms of radius, if 55 Cancri e is the FIRST variable PLANET, WASP 47c is likely to be the SECOND!

@Andrew LePage August 11, 2015 at 12:17

‘True, the radiation environment around gas giants can present issues but a magnetic field even around a moon not much larger than Mars is sufficient protect its atmosphere from erosion making it potentially habitable.’

It is not just the radiation but also the higher energy impacts due to the gravity of gas giants that would erode a moons atmosphere and the larger the planet the more debris it will attract. I am not in favour of moons around gas giants been suitable for life that needs an atmosphere, just to dangerous.

@Michael August 12, 2015 at 14:14

“It is not just the radiation but also the higher energy impacts due to the gravity of gas giants that would erode a moons atmosphere and the larger the planet the more debris it will attract.”

While being in orbit around a gas giant certainly can increase the impact energy of a population of given asteroids and comets, the available literature suggests that it still is not a fatal problem to the potential habitability for moons of sufficient size (maybe on the order of twice the mass of Mars?). For example, with the current population of impactors threatening the Earth, the typical impact velocity is ~17 km/s for asteroids and ~51 km/s for comets. If instead of orbiting the Sun alone as it currently does, the Earth were to be in a two-day orbit around a Jupiter-mass planet which in turn is in a 1 AU orbit around the Sun, the typical impact velocities for this same population of asteroids and comets are now ~29 km/s and ~56 km/s, respectively. For moons in still larger orbits, the impact velocities quickly fall to values not much greater than if the Earth-size moon were orbiting the Sun alone as we do. While such impacts are certainly cause for concern in terms of atmospheric erosion for Mars-size moons, they would not be as big of a concern for larger moons.

If you could cite some peer-reviewed literature to support your claim that moons of gas giants are just too dangerous to be considered potentially habitable because of the impact hazard, I would be genuinely interested in reading it since habitable moons have been a topic of great semi-professional scientific interest of mine for a couple of decades now (and I certainly can not make the claim I am fully aware of ALL of the literature on the subject). Thanks.

@Harry R Ray August 11, 2015 at 9:35

” I urge Any reader with more expertise than me in this field (Andrew LePage et al) to read the entire paper and report back.”

Hmmm… sounds intriguing! Do you have a citation or link to the preprint that you could share?

Andrew LePage: ArXiv: 1508.01853 “Calibrating the pixel-level Kepler imaging data with a causal data driven model”. AUTHORS: Dun Wang, Dan Foreman-Mackey, David Hogg, Bernard Scholkopf, OR: “google” http://www.arxiv.org, click on AstroPh recent(if you do it today) OR AstroPh current month (if you do it tomorrow or later) . OOPS: I meant SHORT cadence(instead of “HIGH”) and LONG cadence(instead of “LOW”). ALSO:Any feedback on the new planets transiting WASP47 would also be appreciated. THANKS!

If you were to only look at the short period giant planets, it is 55 Cancri that is the unusual one. 55 Cancri b is on a 14-day orbit which puts it in the “intermediate period desert” for Jupiter-class planets, while WASP-47b is located squarely in the main clump of hot Jupiters (in fact the discovery paper for WASP-47b describes it as “an entirely typical hot Jupiter”).

The new discoveries put WASP-47 into an entirely new category of systems. Until now there have been no confirmed cases of close neighbours to “standard” hot Jupiters: in the other known multiplanet systems containing hot Jupiters the additional planets have been located much further out. Definitely an interesting system, hopefully it will receive a lot more attention now!

@Andrew LePage August 12, 2015 at 17:26

‘…still is not a fatal problem to the potential habitability for moons of sufficient size (maybe on the order of twice the mass of Mars?)… If instead of orbiting the Sun alone as it currently does, the Earth were to be in a two-day orbit around a Jupiter-mass planet which in turn is in a 1 AU orbit around the Sun, the typical impact velocities for this same population of asteroids and comets are now ~29 km/s and ~56 km/s, respectively.

The energy of impact is quite high at around ~3 times normal, that is a lot of energy for an atmosphere to absorb. Now to get a Mars sized planet around a gas giant would most likely need a much more hefty massed Jupiter or even brown dwarf for an Earth, see article below, which theorises a 1 / 10000 mass ratio between satellite/gas planet mass. Now with this extra mass you have velocities that are getting quite high, I am not sure of the formulae that you used.

‘A common mass scaling for satellite systems of gaseous planets,” by Canup and Ward ‘

‘While such impacts are certainly cause for concern in terms of atmospheric erosion for Mars-size moons, they would not be as big of a concern for larger moons.’

Bigger moons require bigger planets and they invoke bigger velocities of debris.

Andy, you are absolutely right in saying that the 55Cancri system is more UNUSUAL than the WASP 47 system, BUT: I used the word “EXTREME” because most planet formation theorists believe that systems like WASP 47 would fall apart in the migration process BEFORE EVER REACHING THE SUPER-TIGHT FINAL CONFIGURATION! A notable exception is Douglas Lin(who must be VERY HAPPY right now) who has repetedly stated that there MAY be an earth sized planet orbiting INSIDE WASP 12 in a 2 to 1 resonance! We may now have the impetus to check this out with Spitzer.

Sorry, I Meant to say WASP 12b.

I did a comprehensive google search related to WASP47 and found an interesting paper by Marion Neveu-Van Malle et al indicating a possible FOURTH planet(mass undetermined) with an orbital period of 571 + or – 7 days! When these authors FORCE-FEED the NEW data into their older data, this planet candidate may either COMPLETELY DISSAPEAR, or it may CLARIFY the orbital period and the mass (which would be VERY HIGH,since the data were taken by CORALIE, not HARPS). I expect the former of the two above possible outcomes, but I am hoping for the LATTER, because THAT would make the system EVEN MORE ANALOGUS to the 55Cancri system. If this long period candidate exists, ameteaur astronomers would be instrumental in a transit search.

Here’s a Jupiter type alien world for ya:

http://www.americaspace.com/?p=85357

Seeing as it has been pointed out multiple times that “our” Jupiter has been responsible for both saving and threatening life on Earth by deflecting or re-aiming space rocks at our planet, perhaps finding more Jupiter analogs is just as important as finding another Earth. Certainly it will be easier to do so at this stage of the game.

And let us not forget that such exoworlds could also harbor exomoons with the potential to be habitable. And of course let us not forget the hunters, sinkers, and floaters that may inhabit the dense skies of the Jovians themselves.