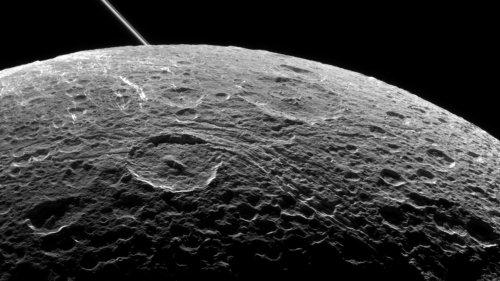

We’re in the immediate aftermath of Cassini’s August 17 flyby of Saturn’s moon Dione. The raw image below gives us not just Dione but a bit of Saturn’s rings in the distance. As always, we’ll have better images than these first, unprocessed arrivals, but let’s use this new one to underscore the fact that this is Cassini’s last close flyby of Dione. I’m always startled to realize that outside the space community, the public is largely unaware that Cassini’s days are numbered. It’s as if these images, once they began, would simply go on forever.

The reality is that processes are already in place for Cassini’s final act. The ‘Grand Finale’ will be the spacecraft’s close pass by Titan (within 4000 kilometers of the cloud tops), followed by its fall into Saturn’s atmosphere on September 15, 2017, a day that will surely be laden with a great deal of introspection. Bear in mind that not long after Cassini’s demise, we’ll also see the end of the Juno mission at Jupiter. We may still have our two Voyagers out there pushing toward the interstellar deep and New Horizons as well, but once we lose Juno, we’ll undergo a hiatus in which there will be no missions on the way to the giant planets.

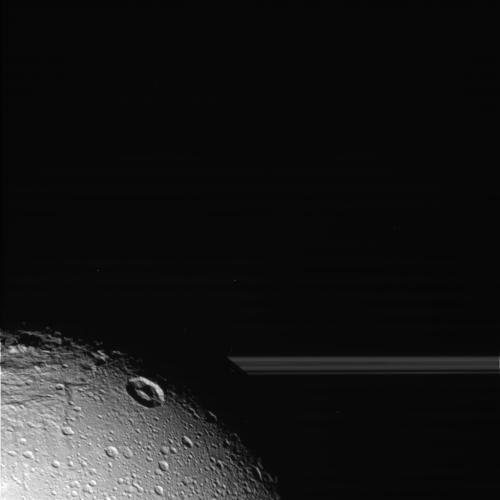

Image: A Cassini image taken on August 17, 2015. The camera was pointing toward Dione, and the image was taken using the CL1 and CL2 filters. This image has not been validated or calibrated. A validated/calibrated image will be archived with the NASA Planetary Data System in 2016. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute.

If you think back to the Voyager days, we were working ahead (on missions like Galileo) even as we tracked the Voyagers ever deeper into the Solar System. Cassini comes out of the Galileo days (it was launched in October of 1997, while Galileo was launched in October eight years earlier), a reminder of the parallel tracks that deep space exploration demands. Given the time to develop a mission and actually get it launched, we should always be a few steps ahead of ourselves. But as of 2018, we’re facing a long slog until the European Space Agency’s JUICE mission (Jupiter Icy Moon Explorer) and whatever NASA comes up with for Europa.

The Planetary Society’s Casey Dreier makes the case that the gap we’re facing will last at least eight years, between Cassini’s demise and any potential Europa mission from NASA. Eight years sounds like a long time, but it’s a best-case scenario, one possible only if we have a Europa mission ready to fly by 2022 and a fully functional SLS (Space Launch System) capable of launching it on a three-year trajectory.

.@elakdawalla 8-year gap is possible only if Europa is ready by 2022 *and* SLS launches it on a 3-year trajectory.

— Casey Dreier (@CaseyDreier) August 18, 2015

We’ve gotten so used to Cassini’s stunning images that it’s hard to imagine they’re going to stop, but perhaps that eight year gap or whatever it turns out to be will remind us of what we’ve had and how hard we have to work to make such missions happen again. All of which is why I’m paying particular attention to these final targeted flybys of places like Dione. The recent flyby should offer helpful comparisons between it and Saturn’s other icy moons. But it will also give us a glimpse of the moon’s north pole, and at a resolution of only a few meters. Cassini’s Composite Infrared Spectrometer will be mapping areas that show unusual thermal anomalies.

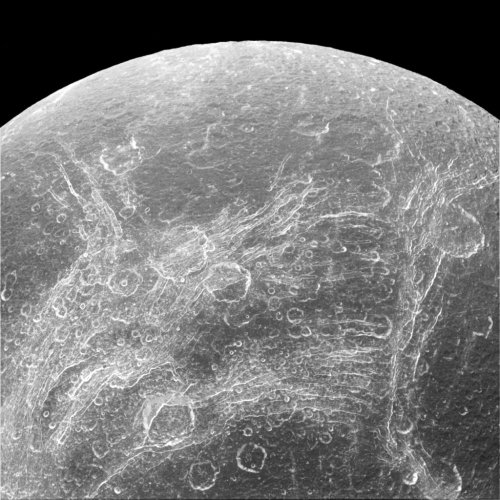

Image: Dione as seen by Cassini on an earlier pass, on April 11, 2015. This view looks toward the trailing hemisphere of Dione. North on Dione is up. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 110,000 kilometers from Dione. Image scale is 660 meters per pixel. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute.

Dione turns out to be an interesting place, quite different from Enceladus. Notice in the image the so-called chasmata, producing what the Voyager team once labelled ‘wispy terrain.’ Features that had once been assumed to be surface deposits of frost were later revealed, by Cassini, to be icy cliffs standing out brightly against the backdrop of surface fractures. We’re probably looking at the result of tidal stress and, as with Enceladus, we’re being given a graphic lesson in how such forces can shape the evolution of a moon both externally and internally.

Giovanni Cassini would discover four moons around Saturn — Tethys, Dione, Iapetus and Rhea — although naming the satellites wouldn’t occur until John Herschel suggested in the mid-19th Century that the four be named after the Titans of classical myth. It’s interesting to note that Dione has two co-orbital ‘moons’ of its own — Helene and Polydeuces — located at Dione’s Lagrangian points 60 degrees ahead and behind Dione. A subsurface ocean is a possibility here, based on observations and modeling of mountains like Janiculum Dorsa, and given inevitable tidal heating, it could explain some of Dione’s surface features.

Image: A view of Saturn’s moon Dione captured by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft during a close flyby on June 16, 2015. The diagonal line near upper left is the rings of Saturn, in the distance. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute.

“Dione has been an enigma, giving hints of active geologic processes, including a transient atmosphere and evidence of ice volcanoes. But we’ve never found the smoking gun. The fifth flyby of Dione will be our last chance,” said Bonnie Buratti, a Cassini science team member at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

Last chance indeed, at least for a time. The close moon flybys of late 2015 will be followed by Cassini’s departure from Saturn’s equatorial plane to begin the set-up for the mission’s final year, in which the spacecraft will move repeatedly between Saturn and the ring system. Let’s hope that a new wave of exploration will get us back to Saturn’s moons so that images like these don’t take on the almost antique air now settling in over Apollo landing site photos, scenes that taunt us with where we have been and make us ask where we are truly bound.

Very sad indeed.

I wish we have orbiters for all major planets, a few Moon bases, one Mars base or more.

The reality is we don’t even have a spacecraft to monitor all the dangerous NEOs yet.

(Tongue in cheek) Second photo:

I see a cave drawing of a running dog!

Tail on the upper left, rear legs at bottom left, right front leg at bottom right, and right ear and head at the upper right!

I guess those Dionians must worship dogs!

Cool picture.

All of which should tell us that continuing to rely exclusively on chemical rockets and gravity assist for outer planet missions is the wrong path. We should be investing in new propulsion technology that can ‘get us there fastest with the mostest’ – in other words, something along the lines of nuclear-electric propulsion for deep space, with SLS as the launch vehicle for large probes, or on-orbit assembly for something even more impressive. As an added bonus, given the nature of such a probe’s propulsion, make it fully reusable, and able to be re-allocated to new targets once its primary mission is complete.

Note, I’m not talking exotic warp drive or even something that can accelerate up to a fraction of ‘c’ – I’m talking about propulsion and spacecraft design that can at least cut travel times down to two or three years. New Horizons did it in eight years to Pluto, which was remarkable, but the downside was it could not slow down. Instead future efforts should be based around propulsion that can get a complex probe to Jupiter or Saturn in 2 or 3 years, and then undertake complex surveys of the major moons, including dropping landers or rovers on the surface is where we should be aiming for.

Does India or China, or any other newcomer, have plans for interplanetary missions before that 8 year gap is passed?

I’m not sanguine about SLS being available. Is there any chance another launcher, suitably modified, could work, e.g. a F9H? Or modify a Europa probe design to work with another launcher?

It’s a pity we don’t have more off-the-shelf launchers and a common platform for a probe, like a very large cubesat, where different instruments can be fitted and integrated. This might reduce costs and uncertainty and allow more missions and more science.

@Malcolm Davis – you want to get their at a reasonable cost and you don’t want to use the current technologies to do this. So do you want to pay far nuclear rockets? You’re going to have to convince a lot of people that they are safe and reliable. Fusion doesn’t exist. So count that out. What options do you suggest we use?

2022 as a best case scenario – for yet another unmanned mission. When I was a kid, Apollo astronauts were my heroes and we’d be landing humans on Mars by 1985. Now we have the tail bits of New Horizons, Cassini and Juno, then nothing.

Our society ignores global warming and ecological destruction like truculent teenagers ignore parents’ warnings not to drink alcohol and drive a car. We continue to live in the basement of our childhood home like 20-something year olds who eat McDonalds and play video games all day because they don’t want to go to college and get a real job.

Society no longer dreams the big dreams. It dreams of the next release of Halo or the newest iPhone. It worships those who entertain us. It glorifies the military which “defends” our planet at the cost of 60 percent of the national budget. It willingly gives up its own privacy and civil rights whenever the government says we must do so to ensure our “security.”

The golden era of space exploration was an expression of humanity’s yearning to grow beyond its limitations and become something greater – to grow to a responsible civilizational adulthood and step out into the wider universe. The decline of space exploration accordingly tracks humanity’s long slide into stagnation and self-satisfaction.

The answer to the paradox of the Drake Equation might be as simple as looking in the mirror.

I imagine that it’s far too late to do this (even if Cassini’s remaining Delta-V capability could do it), but easing it *into* the rings to examine them would provide interesting data and images (although probably not of nearby particles, as the cameras don’t have such close-up view lenses–even the Huygens probe wasn’t “clear in view” until it was about 30 miles from Cassini). Also:

Alex Tolley mentioned something that I’ve ruminated on from time to time, too. Instead of making each probe a “one-off” (or at most a series of two to five spacecraft, as with Pioneers 6 through E, Pioneer 10 & 11, the Venus and Mars Mariners, the Vikings, and the Voyagers), it would seem that developing a series of common spaceframes (for inner solar system and outer solar system missions) and instrument packages would allow probes to be customized for each mission type, using a number of standard components. Communications satellites are now manufactured in just this way. This “Tinker Toy” approach would enable flyby, orbiter, lander, and sample return probes for everything from comets and asteroids to the giant planets (or their moons) to be assembled as per the specific mission requirements, without developing a brand-new design every time, and such probes should be cheaper because their parts would be made in quantity. In addition:

I wouldn’t count on the SLS for probe launchers, either. It’s becoming “The Rocket That Ate NASA’s Budget,” which will be further exacerbated by its very low flight rate. It may be cancelled after its first launch (or perhaps even before) because of its mounting costs and schedule delays. The SpaceX Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy would appear to be the launch vehicles of choice for the foreseeable future.

I’m putting my hopes on developments like lightsail-1: new propulsion systems for micro and nanosats. maybe that won’t give us a new cassini, but the ability to launch an outer solar system flyby missioncheaply and regularly would be a great thing.

Erik Landahl, can’t agree more, on every point.

@Charlie – I am suggesting that for outer planet missions – particularly anything further out than Saturn, traditional chemical rockets and gravity assist is not the best way. Yes, absolutely I’d advocate spacecraft nuclear power and propulsion for these missions. We have been using chemical rockets for close to sixty years, and gravity assist since the days of Pioneers 10 and 11! Its time to throw away the training wheels and do something bolder in space travel (I believe this is the rationale for this very website!).

As for safety and reliability of spacecraft nuclear power and propulsion, we have been using compact nuclear reactors on submarines and aircraft carriers for some decades now. The US safety record in terms of nuclear accidents aboard their submarines is particularly good – not a single accident or significant nuclear incident since the first nuclear powered submarine got underway in the mid 1950s. Modern naval nuclear reactors are compact and safe, and I don’t see any reason why that approach could not be applied to spacecraft nuclear power systems, and if a couple of reactors can power a massive submarine like an Ohio class SSBN indefinitely, it can certainly be applied to power a more compact space probe. That’s an engineering challenge – not a science challenge. Where we have to make progress is in developing spacecraft nuclear propulsion, and there are concepts out there – nuclear electric propulsion in particular – that would make a huge difference to our ability to carry out outer planet missions (and inner planet missions too, including of course, crewed missions to Mars).

I am suggesting we at least make the effort to try to move away from total reliance on chemical rockets and gravity assist, and be more innovative in our approach to space exploration. The alternative – of continuing to do what we’ve done since the 1970s – is a slow, inflexible, and unresponsive approach to exploring the edges of our solar system. This article makes that challenge clear, and we could be waiting decades before we send more probes out there. I don’t think we should have to wait that long.

As for cost, yes there clearly would be an upfront cost, but that would substantially decrease over time as the technology matured (as always happens when a technology matures). Particularly if we end this ‘one use throw away’ mindset that dominates spacecraft design at the moment. Future spacecraft – whether unmanned probes or crewed spacecraft – should be fully reusable, reconfigurable, flexible and responsive to different missions on an ‘as needs’ basis. So for a probe for the outer solar system, equipped with nuclear power and propulsion, if it were assembled in Space at a Lagrange point, would be designed in a manner that could enable it to be used to survey many different worlds over a number of years, and then return home to be upgraded or refurbished. If you have more than one such spacecraft, you can do so much more, and all are designed for reuse. Because the nuclear propulsion system gets you there much faster than gravity assist, the spacecraft can undertake its missions, and then come back and receive updated systems, new computers, new sensors, and then we send it back out again. In the same way Hubble has been systematically updated with new equipment, why not do it for large, reusable and reconfigurable space probes? Once again, this is an engineering challenge – not a science challenge.

So we can stick with the orthodox mindset – single use probes, chemical rockets and gravity assist, decades to get anywhere, high risk of failure if something goes wrong, and then all that effort wasted (imagine if New Horizons had not recovered from its communications problems shortly before Pluto encounter?) – or we can adopt a radical, revolutionary approach which emphasises versatility, reusability, reconfigurability, speed and flexibility through spacecraft nuclear power and propulsion. I’m arguing for a completely new paradigm in deep space exploration.

@Erik Landahl – points well made. I was reading some commentary on the views of current contenders for the 2016 Presidential Election on Space Exploration (both Clinton and a smattering of Republicans, including Trump, Bush, Cruz, etc) this morning, and my heart sank. None of them – not a single candidate – was prepared to say anything vaguely intelligent or meaningful about Space Exploration, or commit to a more robust effort in comparison to the rather anaemic support given by Obama or the current US Congress. Cruz claimed he was going to boost space exploration, but cut Earth-based science – he really does not want us knowing any more about climate change! But no firm policies and commitments, and all Clinton could say was that she wanted to be an astronaut when she was young but was rejected because she was female. That’s her sole contribution – a feminist political statement.

Politicians reflect the attitudes and interests of their voters. Its clear that most people have given up, and a declining interest in science suggests a future where we have become a fat, lazy, ignorant and stupid society (not just Americans – I’m an Australian and there is zero consciousness or interest on the part of the Australian government in relation to Space issues) The US is supposed to be the leader and its not delivering, with no vision, no goals, no money, and no strategy for the future. The small minority of us – scientists, aerospace engineers, writers, and people with a keen interest (I’m in that last category) keep the flame burning as long as we can, but sometimes I wonder if we are fighting a losing battle.

What could prompt us to get off our asses and do something bold and brilliant? I used to think that an overt challenge to US leadership in Space from China or Russia that could generate a new Space Race might be the solution, but that’s already happening and the US is not really responding. They seem content to let it just slip away. The US depends on Russian rockets to get US astronauts into LEO!! That is unacceptable for a so-called leading Space power. So I think that the driver for a renewed focus on Space has to be something really big. The risk of a global catastrophe? A near miss with an NEO, or a long-period comet that gives us a scare? Maybe that could focus our minds. The potential for major scientific and technological breakthroughs that make space exploration much easier and more cost effective? Those are potentially on the horizon, but the money has to be there, either within private industry or from government to turn science R&D into actual usable hardware. At the margins are the more exotic drivers – detection of some evidence of extraterrestrial life within our solar system. Not necessarily dead microbes on Mars – most people won’t get the significance of dead microbes, and the possibility that either we are the evolutionary descendants of those dead bugs, or that they represent a second, independent evolutionary genesis – either of which has profound significance, but neither of which can easily be communicated in today’s media with such a minute attention span. I’m thinking more like complex living multi-cellular lifeforms in Europan oceans, or even more breath-taking, some form of ‘First Contact’ through SETI or other means of detecting evidence of alien life.

I hope at some point we get out of this rut and get back onto the path blazed by Apollo. That we ended Apollo prematurely and did not continue with that vision has been summed up nicely by Chris Kraft, who said ‘we (the US) had become a nation of quitters’. That was 1972. Forty three years later we are still looking at the Moon and wondering when we’ll get back there. Current US space policy does not make me hopeful I’ll see US astronauts back on the lunar surface until the late 2020s at the earliest, and maybe Mars by the middle of this Century. But there is an equal chance that US space leadership will wither and atrophy completely, and the hopes of people like me, and many others who promote human space exploration will taste like ashes of broken dreams.

Enough with the doom and gloom.

Quite possibly, this decade will become known as the beginning of the golden age of space exploration, with student groups running interplanetary cubesat missions (http://www.space.com/21867-cubesat-deep-space-propulsion-kickstarter.html), private companies prospecting and exploiting asteroid resources and a new generation of space telescopes bringing exoplanets and the cosmos into much better focus.

Maybe the US government will even start planning a new wave of conventional interplanetary missions, but by the time those get anywhere much greater things will have happened. Or so one can hope.

@Malcolm Davis – I clearly understand your working points on the answers that you gave back; but I do believe you may have missed the central point of what I was trying to say. The question isn’t really technical is whether or not public opinion will allow the launch of ANY FISSIONABLE materials whatsoever into the environment of space, no matter what fashion may be used to actually implement the transport of the material into the space environment. In other words, the problem is that the public at large. Now fears atomic power and does not want to see the development of any more type of nuclear systems, whether for commercial or scientific development or what have you. The second point was the fact that I mentioned cost and that is something that is quite a bit on everyone’s mind, mainly the fact that we now have a nearly twenty trillion dollar debt in the government’s domain (most of it borrowed from China) and we have quite a bit of other issues that are also competing for dollars. I look at the cost issue and price tag as being something that would probably be a real dealbreaker rather than the nuclear issues themselves. That’s why I stated how would you be able to create new propulsion systems under these constraints.

@Charlie – thanks for your comment back. I understand your point re public fear of nuclear power. After Chernobyl and Fukushima, I can understand them having concerns about safety. But I think this is an issue that will be resolved through effective public education about nuclear safety and nuclear technology issues, and I go back to my point about subs. People don’t fear nuclear subs. They accept them as commonplace. Go to San Diego, or Pearl Harbour, and there are nuclear subs sitting tied up at dock close to populated areas. The technology for nuclear spacecraft power is similar – a small, compact reactor, that could be carried up into orbit safely and then integrated into a main spacecraft. The launch phase is the issue – I can’t see why people would worry about a nuclear reactor on a spacecraft millions of kilometres out in Space, and when they are educated about the benefits of nuclear over chemical rockets, I think that provided states can demonstrate a safe launch process, with safety backups, it should work. The bottom line is that unless the human race wants forever to be stuck in the inner solar system, or only be able to do outer solar system exploration very slowly, nuclear power is really the only viable solution. Not RTGs – reactors for power and propulsion. If we turn our back on this because we are afraid of the technology then we are adopting a very luddite mindset for the future.

The cost issue is another one altogether, and I accept that its a problem, but the fact is, space is always going to be expensive. Why do we talk about space exploration on this website – let alone interstellar travel – if its always never going to happen because its too expensive? We may as well give up! No – what is needed is a strong case for both unmanned probes and crewed missions to the Moon, Mars and then beyond over the next 100 years. That will take people like you and I being able to promote ideas to decision-makers, justify the expense and justify the benefits of being a bit more ambitious and innovative in our approach to space, as opposed to doing more of the same in terms of how we do space exploration.

If you look at the excitement that New Horizons generated with Pluto, we need more of that, and to reach a wider audience on a continuing basis. Maybe that means our next probes need to film in IMAX, or with consumer VR now due to hit the stores in the next two years, people can put on a headset and watch a Mars rover as if they were there standing on the surface in full 1080p. There needs to be an effort to engage with a wider audience on a continuing basis, so that more people are excited about space exploration more of the time, and then demand answers from their representatives in government about ‘why aren’t we doing more’? That’s the only way we are going to convince governments to properly fund space exploration – if the voters demand it!

That is the rub. Can they? How can they demonstrate that accidents won’t release radioactive material? Unlike launching subs, rocket launches are failure prone. As we also saw with the Russian Progress failure, there is the chance that a reactor will reenter from space is also a risk. I well recall teh fuss over the Cassini earth-Venus gravity assists made by some some groups, and that was for a small plutonium RTG. I am sympathetic to the idea of using advanced reactors in space, primarily for the outer solar system, but I think we need to demonstrate a much safer launch system or a par with aircraft reliability.

http://www.spacevr.co/#spacevr

@Alex – simply put, we must. There has to be a way to safely launch nuclear reactors with fissile material into Space. Otherwise spacecraft nuclear power and propulsion will never get anywhere. Maybe the answer is something other than rockets. R&D into scramjet technology, such as the Reaction Engines SABRE engine for the Skylon spaceplane, and combined-cycle engines is the most obvious path forward, and a single stage or two stage to orbit fully reusable spaceplane is the obvious way to go, even if its just for crew to orbital platforms, or small cargo, such as a compact nuclear power module might be circa 2020s-30s. That will take time to develop, but in the longer-term perspective, an R&D phase lasting into the 2030s and ultimately delivering a better solution than rockets is worthwhile in my view. Full reusability, better cost efficiencies, better safety, airline style approaches to operations. Short of developing the Space Elevator, single stage or two stage to orbit spaceplanes have to be the next logical step in Earth to LEO travel. That’s where money needs to be invested.

Then use large, reusable or partially expendable rockets (i.e. SpaceX approach) for bulk cargo. To me, its quite obvious that’s the future.

Thanks for the link on SpaceVR – will have a look!

If only we could get the ‘Space-coach fleet’ concept up and running then that could provide the mindset that the whole solar system is open for exploration and utilization… hmm, now where did I hear about that wonderful design… wink wink, nudge nudge :D

Malcolm made a very salient point when he said…

“Its clear that most people have given up, and a declining interest in science suggests a future where we have become a fat, lazy, ignorant and stupid society…”

I’m English and while our government has recently bought into ESA manned spaceflight it has shown a variable interest over my lifetime (I was born in ’71 just as we cancelled our spaceprogram!). I’m grateful that at least we do want to be in with the bigger players, so that much is different. However, the decline not just in society but in interest is rampant here with the average Joe. I have spent all afternoon trying in vain to recall anyone I know who has even a passing knowledge of what we’ve been doing in the solar system for the last 50 years, other than Voyager and now New Horizons (my immediate aquaintances have soaked up my references through osmosis as I try to deseminate our endeavours but ‘you can’t make the horse drink’ if their interests lay elsewhere).

This segues into the ‘fissionable material’ launches issue. It seems to me that the tiny minority of the populus that are ‘space advocates’ know enough about the dangers and benefits to be split into two camps… those for it and those against. The huge majority of the population hold little interest in space exploration/utilization and they just think of the danger and how anyone must be insane to risk it, so ‘no thankyou’. Is education the problem or are we still in a comfortable place where “that’s for the future to worry about”-mentality is still at play, I don’t know?

In our Houses of Parliament we need more MPs with a degree in science to be able to steer National Interest (IIRC, M. Thatcher had a degree in Chemistry in the ’80s and stood alongside just three or four politicians who also had science degrees… out of 600+ !!). We need leaders with a bigger scope to help usher in the view that to look upwards has so many benefits in the mid to long term. Afterall, perhaps there is an argument to say that what good has a parliament full of MPs with degrees in Business and Law done for us when we’ve been declining and through economic disaster?! £50 Billion of taxpayers money to a bunch of bankers… and they still keep their huge bonuses? I’m close to ranting…

I’m not too sure we can change this and we may have to wait for things to get a lot worse before the ‘voters’ finally wake up to the fact that there are huge gains to be made out in the solar system… that’s why the private sector will lead the way and they’ll be in the perfect position to make the sluggish governments of the world cow-tow to the new paradigm. At least Eniac’s cubesat mention will help build the infrastructure in these early stages of the interim.

Until then, I’ll have to speak to Alex about booking a seat on a Space Coach…