Garrett P. Serviss was a writer whose name has been obscured by time, but in his day, which would be the late 19th and early 20th Century, he was esteemed as a popularizer of astronomy. He began with the New York Sun but went on to write fifteen books, eight of which focused on the field. He was also a science fiction author whose Edison’s Conquest of Mars (1898) used Wellsian ideas right out of War of the Worlds. It was a sequel to an earlier story, involving master inventor Thomas Edison in combat against the Martians both on the Martian surface and off it.

I think this is the first appearance of spacesuits in fiction. In any case, Serviss anticipates the ‘space opera’ to come, and will always have a place in the history of science fiction. I can only wonder what he would have made of the Dawn mission at Ceres. In Edison’s Conquest of Mars, he refers to a race of ‘Cerenites’ who are, because of the low gravity of their world, about forty feet tall. They are at war with the Martians, and thus allies of Earth.

Image: Author and science popularizer Garrett P. Serviss.

Forgive the digression, but I’m always interested in the work of people who bring science to the public, and it’s clear that Serviss’ interest in Ceres would have been profound, as works like Other Worlds: Their Nature, Possibilities and Habitability in the Light of the Latest Discoveries (1901) demonstrate. From Other Worlds, this look at Ceres and the asteroid belt as understood at the turn of the 20th Century:

The entire surface of the largest asteroid, Ceres, does not equal the republic of Mexico in area. But Ceres itself is gigantic in comparison with the vast majority of the asteroids, many of which, it is believed, do not exceed twenty miles in diameter, while there may be hundreds or thousands of others still smaller—ten miles, five miles, or perhaps only a few rods, in diameter!

Hundreds or thousands indeed. Another Serviss book, Astronomy with an Opera-glass (1888), holds up pretty well even today. Another thing I like about him is that in his science fiction, he writes scientists into the plot. Not just Edison, but Edward Emerson Barnard and Wilhelm Röntgen, to name but a few.

A New Look at Occator

But enough of early science fiction and on to Ceres today. Even before Dawn, we had made recent strides, nailing Ceres’ rotation rate, for example, by 2007, at 9.074170 hours. Those odd bright spots on the surface were evidently picked up in 2003 Hubble measurements, which showed a spot that moved with Ceres’ rotation, and water vapor plumes erupting from the surface have been reported using Herschel data, suggesting possible volcano ice geysers.

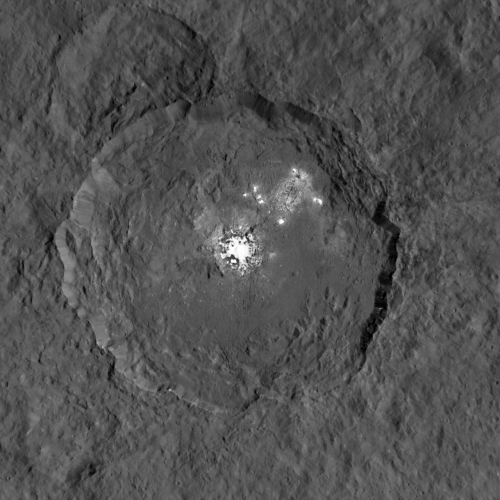

Now, of course, we’ve homed in on the bright spots in Ceres’ Occator crater, and the speculation about their origin continues. Are we looking at a relatively recent impact crater that has revealed bright water ice? Cryo-volcanism or icy geysers have also been suggested. As of today, we still don’t know whether the bright spots are made of ice, or evaporated salts, or some other material. A new study using the HARPS spectrograph at La Silla (Chile) has just appeared, showing us that whatever they are, the bright spots show changes over time.

Lead author Paolo Molaro (INAF-Trieste Astronomical Observatory) explains the method:

“As soon as the Dawn spacecraft revealed the mysterious bright spots on the surface of Ceres, I immediately thought of the possible measurable effects from Earth. As Ceres rotates the spots approach the Earth and then recede again, which affects the spectrum of the reflected sunlight arriving at Earth.”

Image: The bright spots on Ceres imaged by the Dawn spacecraft.

The changes Molaro’s team has found are subtle — remember that nine-hour rotation rate, which means the motion of the spots toward and away from Earth is on the order of 20 kilometers per hour. But the Doppler shift caused by the motion can be revealed by an instrument as sensitive as HARPS. Over two nights of observation in July and August of 2015, the researchers found the spectrum changes they expected to see from this rotation, but they also recorded random variations from night to night that came as a surprise.

The paper lays out a possible cause: The bright spots could be providing atmosphere in this region of Ceres, which would confirm the earlier Herschel water vapor detection. Pointing toward this conclusion is the fact that the bright spots appear to fade by dusk, an indication that sunlight may play a significant role, possibly heating up ice just beneath the surface and causing the emergence of plumes:

It is possible to speculate that a volatile substance could evaporate from the inside and freezes when it reaches the surface in shade. When it arrives on the illuminated hemisphere, the patches may change quickly under the action of the solar radiation losing most of its reflectivity power when it is in the receding hemisphere. This could explain why we do not see an increase in positive radial velocities, but all the changes in the radial velocity curves are characterized by negative values. After being melted by the solar heat, the patches can form again during the four-hours-and-a-half duration of the night, but not exactly in the previous fashion, thus the RV curve varies from one rotation to the other. It is possible that the cycle of evaporation and freezing could last more than one rotational period and so the changes in the albedo which are responsible of the variations in the radial velocity.

As this ESO news release points out, the volatile substances evaporating under solar radiation could be freshly exposed water ice, or perhaps hydrated magnesium sulfates. The spots are brightest in the morning when their plume activity reflects sunlight effectively, but as they evaporate, the loss of reflectivity produces the changes analyzed in the HARPS data. We can add to the mix a recent paper in Nature (see below) that reports localized bright areas consistent with hydrated magnesium sulfates and probable sublimation of water ice.

So the mysterious bright spots of Ceres continue to tantalize us. As the paper notes, the fact that we find several bright spots in the same basin (Occator crater) seems to point to a volcano-like origin, but that would imply that an isolated dwarf planet can be thermodynamically active. Such activity is no surprise in large satellites around the gas giants, where tidal effects are assumed to play a major role, but its sources on Ceres will need further investigation.

The paper is Molaro et al., “Daily variability of Ceres’ Albedo detected by means of radial velocities changes of the reflected sunlight,” Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Vol. 458, No. 1 (2016), L-54-L58 (abstract). The Nature paper is Natues et al., “Sublimation in bright spots on (1) Ceres,” Nature Vol. 528 (10 December 2015), 237-240 (abstract).

This seems to be EXTREMELY ANALOGOUS to the nitrogen fueled guysers on Triton but without the plume trails visible on Triton due to the circulation patterns of Triton’ upper atmousphere. Apparently, Ceres MUST have SOME KIND of an atmosphere, no matter HOW TENUOUS, to support a VERY TEMPORARY haze at noontime.

Isn’t the water out gassing going to have more in common with comets than “geologic” activity of planets?

Only if the H2O being released is in SOLID FORM(i.e. ice)AT THE RELEASE SIGHT! On Triton, non-transparent nitrogen ice heats up from sunlight filtered through a THIN FILM of TRANSPARENT nitrogen ice at the surface, expands, and then EXPLODES in the same way volcanoes on earth erupt. Dawn has determined that, at the SURFACE< Occator Crater's bright spots are made of(most likely Epsom)SALT! If there is water ice just a few centimeters or a few inches BELOW the salt surface, the SAME PROCESS as what occurs on Triton, will most likely occur on Ceres as well!

I feel the dust covering is thermally insulating the interior quite well, I wonder if they found ammonia in the outgassed material.

You have to be in the right mindset to get through the turgid prose, but “Edison’s Conquest of Mars” is available at Gutenberg:

http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/19141

“Astronomy with an opera-glass” is not bad:

https://archive.org/details/astronomywithope00servuoft

Available as audio book too. I don’t recommend it as a story, but maybe if one is interested in the history of science fiction. Edison and Wells didn’t want anything to do with it. While War of the Worlds used several interesting concepts very early on, like laser and biohazard, Serviss’ ideas about electrical propulsion and magnetic comets were not as good.

H.P. Lovecraft fans will recognize the name Serviss as H.P. mentions it (and his role as an astronomy popularizer) in “Beyond the Wall of Sleep.”

Could a lander/rover with MER capability (obviously with a different EDL setup) be sent to Occator in a Discovery class budget? This seems like the cheapest and easiest was to get close to possible cryovolcanism in the solar system, although I also like proposals to land next to some active ‘spider terrain’ on Mars (yes, different phenomena I know)

P

I remember Edison’s Conquest of Mars. It was another one of those “firsts” that laid the foundation for later space opera, like E.E. “Doc” Smith’s later Skylark series. Garret P. Serviss doesn’t just predict space suits, either. Edison invents a disintegrator ray to battle the Martians – the first fictional reference to a popular space opera weapon. Serviss was a bit less inventive with Edison’s space ships. They use electrical generators to create repulsive forces that operate quite similarly to the “apergy” in Percy Greg’s Across the Zodiac (1880). And they are naturally threatened by meteroids on their way to Mars. But hey, this type of anti-gravity drive obeys Newton’s 3rd law and only work if you are near a planetary mass you can push against and use as reaction mass!

The Martian’s space propulsion is rather more interesting. They detonate a mysterious explosive of incredible power underneath their “space-cars” to violently propel them into space. This does great damage to Earth cities when the Martians retreat from Earth. Here we have perhaps the earliest reference to external pulsed explosive propulsion, decades before Project Orion. It’s very interesting to see this idea in fictional form this early, though realistically the Martians should sub-divide their propulsive phase into many small explosions rather than the one gigantic blast they seem to favor – the acceleration force would kill them instantly. Many early writers blithely ignored acceleration limits when writing about launching space travelers out of a gun and the like, of course.

This story is also the earliest to feature a human counter-invasion against alien attackers, so far as I am aware. So here Serviss was laying the groundwork for later stories showing humans inventing or reverse-engineering space travel and advanced weapons to defend Earth from alien invaders by fighting them in space, like Macross.

All in all, Edison’s Conquest of Mars is a rather interesting early story, despite the hilarious title. Unlike later authors, he even dealt with the issues of translation that would arise when you visited an alien planet, rather than assuming the existence of telepathy or universal translators to speed the plot along. Another interesting fact is that Serviss explains why the Martians didn’t develop disintegrators and electrical repulsion drives themselves. As it turns out, Mars lacks the necessary chemical elements to make such devices, even though the Martians are quite smart enough to have invented them. This could be a reality for inhabitants of planets somewhat poorer in heavier elements than Earth. If uranium were almost non-existent in Earth’s crust, we could never have developed the nuclear reactor, the fission bomb, nor the hydrogen bomb since that requires a fission device to set it off.

Personally I was rather amused to see Lord Kelvin among Edison’s army of scientists, wearing a vac suit and sporting a pair of disintegrator pistols holstered under each shoulder. Yes, that is the same Lord Kelvin who said, at one point or another, that nothing new remained to be discovered in physics, x-rays would prove to a hoax, radio waves would have no practical application, and flying machines were entirely impossible. No doubt the real Lord Kelvin regarded interplanetary travel and disintegrator rays as utter nonsense. Granted, an invasion by Martians might have changed his opinion regarding the flying machines.

Amusingly enough, though, the story bears Lord Kelvin out regarding radio waves. Edison’s ships communicate by means of flags and heliographs during the day and flashing electrical lights at night. During EVA, astronauts string wires between each other when they wish to talk, so that they can use a suit-to-suit telephone. Nowadays this seems ludicrous to us, yet it goes to show how even the most futuristic authors can overlook future solutions to problems by attempting to solve them with current methods.

Wires (even if here conducting sound directly) would have the massive advantage that the signal couldn’t be intercepted. I think ludicrous = ingenious on that one. Also, Lord Kelvin would convert to the completely opposite view when faced with his predictive failure. My pick is that he would be touting that humanity could outdo even the science Martians, with the zeal only possible in a new convert.

If Ceres is shown to have a subsurface ocean perhaps these salt deposits could act as doorways to below, any water and salts would lower the melting point of the mixture so a heated penetrator could move its way down.

One thing in solar system exploration that we have NOT seen(except for the Moon) is a MOVIE CAMERA on a spacecraft! Obviously,for Mars, Venus, Titan, and the asteroids, it would be IMPRACTICAL, because nothing hardly ever MOVES on these places. Philae was too small and its life expectancy was too short to install a movie camera. ENTER CERES: I bet THE FARM that there is some kind of movement going on in Occator Crater around noontime EVERY DAY! It is probably NOT a violent environment either. This place SCREAMS for some kind of a movie camera to find out what the heck is going on there!

I agree. Imax camera on ceres explorer rover will be the next game of thrones.

Wait…what fading of bright spots on ceres? I watched the nasa footage too and it continued to produce light even in shadow of the dark side. That implied energy absorbtion and slow release over time. Thats unique if its ice crystals in non-atmosphere.

Unobtanium comes to mind. Kyber does too.

BREAKING NEWS: Salt has been CONFIRMED as the bright surface deposits in Occator crater, but, HOLD ONTO YOUR HATS: Ceres’ SECOND brightest spot(at Oxo crater)is composed of ONE HUNDRED PERCENT WATER ICE AT THE SURFACE!! What’s even WIERDER is that OCCATOR crater’s MAIN CENTRAL SPOT GROWS AND SHRINKS OVER TIME! This must mean that the salt is in an EXTREMELY HYDRATED FORM that LITERALLY EXPLODES when it gets too hot, CONFIRMING my “Triton guyser” hypothesis, but at a MICROSCOPIC LEVEL! The remaining UNHYDRATED salt is jettisoned by the explosions and falls back near the crater rims, mixing itself in with the regolith, and essentially disappearing from sight. Unfortunately, this process may be MUCH MORE VIOLENT than I proposed in my above comment, making this place a very dangerous place for a rover to visit. DARNNNNN!!!!

An orbiter, rover and impactor might be a good way to go. The rover is on the ground first and then an impactor hits the deposit to explode it into space so the orbiter and rover can examine the contents deep down through the radio/laser link and the rover analysing the debris and solid deposits on the ground as well. Might be able to test the impact idea for Europa and get some useful data.

The locations of the two water vapor plumes detected by the Herschel infra-red telescope are a near perfect match for Occator crater and for Oxo crater. Somehow, I do NOT think this is a co-incidence. NOW, FOR THE REALLY BIG QUESTION: JWST is able to CONFIRM AT FIVE SIGMA, life on an earth-like planet transeting a NEARBY white dwarf star. Unfortunately. JWST CANNOT confirm life in Enceladus’ plumes or in Saturn’s E ring due to infra-red pollution from Saturn, itself. If JWST could position itself so that the Sun and Ceres are on OPPOSITE SIDES of the spacecraft, and infra-red pollution is at an ABSOLUTE MINIMUM, could JWST ALSO confirm at five sigma, life in Occator crater’s plumes or haze layer? I would appreciate as much feedback from readers on this question as possible, because it will probably be a decade before NASA or ESA can land something that could confirm life at the five sigma level. I here RUMORS that either a Chinese or joint Chinese-Russian lander is in the works for a landing 3 or 4 years down the road, but I SERIOUSLY DOUBT that it could confirm life much above the three sigma level.