Cassini’s final months are stuffed with daring science, the kind of operations you’d never venture early in a mission of this magnitude for fear you’d lose the spacecraft. With the end in sight for Cassini, though, ramping up the science return seems worth the risk. And while diving through the narrow gap between Saturn and its rings seems to be asking for trouble, the results of the first plunge on April 26 show that the region is more dust-free than expected.

“The region between the rings and Saturn is ‘the big empty,’ apparently,” says Cassini Project Manager Earl Maize of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “Cassini will stay the course, while the scientists work on the mystery of why the dust level is much lower than expected.”

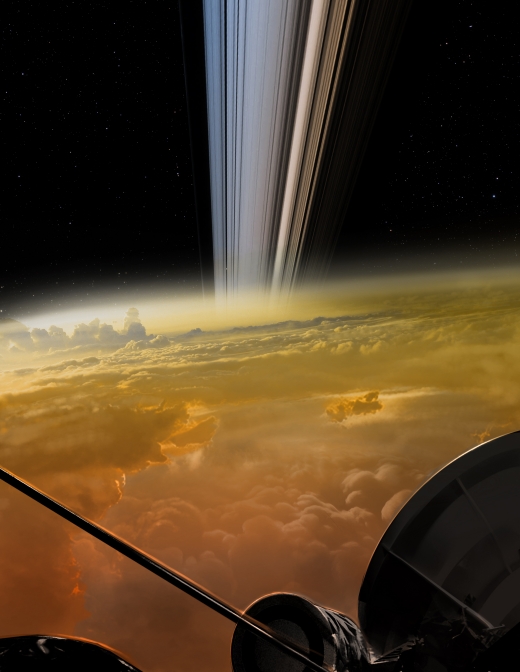

Image: This artist’s concept shows an over-the-shoulder view of Cassini making one of its Grand Finale dives over Saturn. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

The region between Saturn and its rings was thought, based on previous models of the ring particle environment, to be free of large particles that could cripple the spacecraft. But it seemed prudent to rotate Cassini so its 4-meter antenna became a ‘bumper’ of sorts that could shield its scientific instrumentation during the dive. Such changes in orientation affect how the spacecraft takes data.

In fact, as we see in this JPL news release, Cassini’s Radio and Plasma Wave Science instrument and its magnetometer were the only two science instruments whose sensors were not in the shadow of the antenna in the first dive. It was the RPWS instrument that measured the particle count during the crossing of the ring plane and found only a few scattered hits.

“It was a bit disorienting — we weren’t hearing what we expected to hear,” says William Kurth, RPWS team lead at the University of Iowa, Iowa City. “I’ve listened to our data from the first dive several times and I can probably count on my hands the number of dust particle impacts I hear.”

Image: This video represents data collected by the Radio and Plasma Wave Science instrument on NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, as it crossed through the gap between Saturn and its rings on April 26, 2017, during the first dive of the mission’s Grand Finale. The instrument is able to record ring particles striking the spacecraft in its data. In the data from this dive, there is virtually no detectable peak in pops and cracks that represent ring particles striking the spacecraft. The lack of discernible pops and cracks indicates the region is largely free of small particles. Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Iowa.

The particles the craft did encounter were no more than 1 micron across, about the size of particles you would find in smoke. Now we have another ring plane crossing today at 1538 EDT (1938 UTC), during which Cassini will be out of contact during closest approach to Saturn. We’ll get data return on May 3. After today, 20 ring dives will remain, with four of them passing through the innermost fringes of the rings and demanding the use of the antenna as shield. But the low dust level means that most dives will not need the shield configuration.

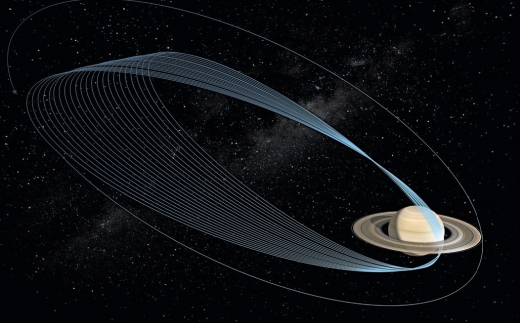

Image: Cassini will perform 22 orbits of Saturn during the Grand Finale. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

Each of the so-called Grand Finale orbits takes about six and a half days to complete, with the spacecraft’s speed at closest approach to Saturn in each orbit ranging from 35 to 33.6 kilometers per second. This second orbit in the series gives Cassini’s imaging cameras (its Imaging Science Subsystem) a chance to observe the rings at extremely high phase angles while the Sun is directly behind Saturn — this should allow small features like ‘ringlets’ within the rings to be observed. The spacecraft will come within 2930 kilometers of the 1-bar level in Saturn’s atmosphere while passing some 4780 kilometers from the inner edge of the D ring.

Fantastic stuff. I am very keen to see what images will materialise. Surely nothing so crisp and colourful as the artists concept due to limitations in the camera technology?

In any case, what is the ETA on first images coming through?

Joe, you can already see some of the raw imagery, though of course it is unprocessed:

https://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/galleries/raw-images/

There is a Chesley Bonestell painting from Conquest of Space that shows the rings of Saturn as seen from Saturn! This blew me away in 1952 when I was 11. I didn’t see the color version until years later.

I was astounded by the perspective , never thought of that point of view before.

I think the original is in the Hayden Planetarium?

I’m hoping that the shot JPL plans to take right at the end–letting Cassini’s camera look up at the rings as, or *just* before, it encounters Saturn’s atmosphere–reaches Earth and shows what ol’ Chesley painted back then!

Cheers Paul, that’s a great resource.

Also, superb ongoing work with the site. Have been a reader for the best part of a decade now. You’re a harder worker than the Cassini probe!

Great to have you here, Joe. And thank you for the compliment, but believe me, *nothing* has worked harder than Cassini!

A bit early to draw conclusions from one deep dive, so I wouldn’t be “closing the brolly” just yet until there are few such passes. If the cis-ring space is indeed universally dust free I wonder if this is an early a clue as to the rings ‘ age? A key question that Cassini’s Grande finale hopes to answer and which may also have implications for Enceladus too , possibly even habitable versus habitable and inhabited. Early days but ever optimistic ….

Paul Gilster wrote above:

“But it seemed prudent to rotate Cassini so its 4-meter antenna became a ‘bumper’ of sorts that could shield its scientific instrumentation during the dive.”

In the spirit of what we look forward to (plus injecting a little sympathetic magic here), *maybe* within the lifetimes of some readers here: It’s not a -bumper-, but an ^erosion shield^…

The dives corroborate our how accurate is our knowledge of the gravity and mass of Saturn.

The refinements to our knowledge on Saturn’s mass is accomplished by the Doppler shift in the radio signals from Cassini as it passes near Saturn and through it’s gravitational field.

But what if anything does the paucity of dust in the cis-annular “big empty” region say as to the rings age . Surely if they were formed relatively recently , within the last hundred million years , as has recently been suggested (along with all current moons proximal to Titan ) then there would be more debris /particulate matter? The left overs of a gravitationally disaggregated moon/s.

That’s a good question, Ashley Baldwin. If you are making the assumption that the rings are much older and the dust was cleared by gravitational, electromagnetic fields, micrometeorites, or some other cause over billions of years. The only way I know that science can find out how old the rings is the CRE or cosmic ray exposure age. We would have to have a piece or sample of ring rock though.

The idea that the rings are only as old as the dinosaurs is now thought to be obsolete by astrophysicists according to new data from Cassini. https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/cassini/media/cassini20071212.html

The answer to this question (“How old are Saturn’s rings?”), as well as the details of how the ring material is–as Larry Esposito said–recycled at different rates in different parts of the ring system, make a compelling case for a dedicated ring probe Saturn orbiter. Also:

Such a mission could investigate the electrostatic and/or electromagnetic phenomena such as the ring spokes that were detected from afar by the Voyager spacecraft, as well as physically examine actual pieces of the rings. It might even be possible for the spacecraft to utilize the forces that elevate the spokes above the rings in order to travel across them, although a low-thrust electrical propulsion system (or perhaps better, an electrodynamic tether propulsion system) could also enable such slow maneuvers across the ring system, in order to examine the different materials found at different distances from Saturn.

And–I forgot to mention above–imagine the spectacular, “Bonestell-esque” pictures that such a Saturn ring probe orbiter could take, both from within and above the rings!

Thanks , all round. A reassuring thought if only with Enceladus exploration in mind. Testable too , by Cassini, as if indeed old the rings are likely to be far more massive than has been traditionally believed. Something the Grand Finale dives aim to constrain.

That just leaves the mystery of where such a small moon finds enough intrinsic energy to maintain a substantial liquid ocean. Europa style tidal interactions don’t seem to apply as yet and it’s far too small to have a sufficient radio nucleotide load .

Up to 40% of the selection “weighting ” for New Frontiers mission selection comes from the science case though, so all of this bodes well for the ” Ocean Worlds ” theme coming up on the rails . Especially given the recent molecular hydrogen discovery in Enceladus plumes. Watch out for Enceladus Life Finder , the likely most robust of the numerous Ocean Worlds submissions given its circumscribed science goal, experience defined costings and small but potent instrument payload . All against a backdrop of proven Cassini heritage ( and staff) . It’s biggest task will be in overcoming risk averse assessors misgivings that solar power can indeed deliver to and at 9AU.

We might not be able to use a CRE date to easily since the boulders are always shattering and coming together again since they are ice which might reset the CRE. We might have to have a solid piece of rock which was once exposed to the cosmic rays.

Saturn has an inclination to our Earth and Sun so that the rings can be seen as an ellipse or their wide part so maybe the solar wind does something to the dust which removes it from between the rings and planet like ionizes it or gives it a charge which helps to remove it, the electromagnetic field of Saturn or the solar wind ? I’d like to see what ideas astrophysicists can come up with to explain why they are surprised there is not any dust between the rings and Saturn.

Great work! I understand the environmental issues with letting the craft go on into deep space, but isn’t the temptation hard to resist? A chance to let the wonderful work of the orbiter continue, would be hard to pass up. I worked in astrophysics for Cal Tech for many years, and I know there is always a long range plan. Best for the future.

Cassini has already made its third pass through the rings. Lots of great images here:

http://www.americaspace.com/2017/05/10/grand-finale-part-3-cassini-completes-third-ring-dive-sees-bright-clouds-on-titan/

The Planetary Society has a display of all the moons of Saturn to scale:

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/emily-lakdawalla/2017/0517-saturns-small-satellites-to-scale.html

And you can always count on Saturn to take a beautiful photograph:

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/guest-blogs/2017/0516-cassinis-grand-finale-portrait-of-saturn.html

Cassini completes ring crossing number 8:

http://www.americaspace.com/2017/06/11/grand-final-part-4-cassini-completes-eighth-ring-crossing-and-a-tour-of-saturns-moons/

We are halfway through Cassini’s Grand Finale:

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/emily-lakdawalla/2017/0703-cassini-end-preview-preview.html

What Cassini saw on Titan: ‘Dunes of the Arabian desert’ but made of water chips, not sand

Jacob Margolis

July 25 2017

After 13 years, the Cassini spacecraft made one of its last passes of Saturn’s moon Titan in an effort to learn more about its atmosphere. This, before the spacecraft disintegrates as it plunges into Saturn on September 15.

http://www.scpr.org/news/2017/07/25/74094/what-cassini-saw-on-titan-dunes-of-the-arabian-des/

Just five more ring crossings to go:

http://www.americaspace.com/2017/08/09/only-5-ring-crossings-left-as-cassini-nears-end-of-historic-mission-at-saturn/