No one said this was going to be easy. Delays involving the James Webb Space Telescope are frustrating, with NASA now talking about a launch in mid-2020 instead of next year, and the uncertain prospect of a great deal of further testing and new expenditures that could run the project over budget, necessitating further congressional approval. It’s hard to look back at the original Webb projections without wincing. When first proposed, estimates on the space observatory ran up to $3.5 billion, a hefty price tag indeed, though the science payoff looked to be immense. It was in 2011 that a figure of $8 billion emerged; the project now has a Congressionally-mandated cost cap of $8.8 billion.

And now, looking forward, we have Thomas Zurbuchen, speaking for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, explicitly saying “We don’t really fully know what the exact cost will be…”

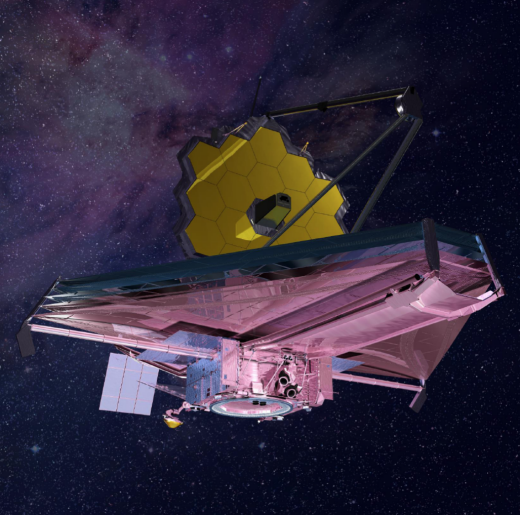

Image: Illustration of NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope. Credit: NASA.

Projects this big invariably take us into the realm of acronyms, with the project’s Standing Review Board (SRB) concluding that further time is necessary to integrate the various components of JWST. But we also learn that NASA is setting up an Independent Review Board (IRB) to complement the SRB findings. The space agency will look at the findings from both boards and consider their recommendations by way of taking us to a more specific launch schedule, with an assessment due in a report to Congress this summer. This NASA news release also talks about “Additional steps to address project challenges include increasing NASA engineering oversight, personnel changes, and new management reporting structures.”

There’s no question about the challenges JWST presents. Its spacecraft element is made up of the huge sunshield (the size of a tennis court), along with the spacecraft bus including the flight avionics, power system and solar panels. The collapsible sun shield must be folded and re-folded during the test process. Eventually it must be mated with the 6.5 meter telescope and science payload. The latter were successfully tested in 2017 at Johnson Space Center, with the telescope element being delivered to Northrop Grumman earlier this year.

Both halves of the observatory are now in the same facility for the first time. Ahead for the spacecraft element is vibrational, acoustic and thermal testing, necessary before the observatory can be fully integrated and pronounced ready for flight. The area of concern is the sun shield and bus, both developed by Northrop Grumman. Contributing to the delay, according to this Lee Billings essay, is a series of tears that appeared on the shield while being tested for deployment. The shield is said to have created a snagging hazard, forcing the addition of springs to prevent it from sagging. Other errors have involved the spacecraft thrusters.

What to do? Northrop Grumman teams are now working on the telescope 24 hours a day, while NASA is calling in the cavalry, as Marina Koren describes in The Atlantic:

Nasa announced some measures they would take at Northrop Grumman’s facility in California, where all of Webb’s parts currently reside. The space agency said they will increase engineering oversight at the facility in Redondo Beach and will track the company’s test reports on a weekly basis. Senior management from nasa’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, where much of the telescope was constructed, will work out of Northrop Grumman’s offices on a permanent basis. Northrop Grumman’s project manager for Webb will report directly to C-suite level executives at the company “to help remove roadblocks to success within the company,” the officials said.

Northrop Grumman is the prime contractor for JWST, but it appears that deeper NASA involvement in the process is forced by events. Ahead for the observatory is the tough environmental testing of sun shield and bus that the telescope and science instruments have already received. This in itself is a matter of several months, after which JWST can be assembled and tested in final form. The feeling at this end is that JWST has become so expensive, so pivotal in our astronomical roadmap, that it is too big and too expensive to fail.

That means its launch and deployment are going to be fraught with tension. 100 times more powerful than Hubble, JWST will operate 1.5 million kilometers from Earth, meaning that servicing missions by astronauts like Hubble has received will not happen. What would the path forward be if we lost JWST because the complex deployment process failed?

Also worth pondering: What will be the effect of any JWST overspending on the WFIRST mission? The Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope has had its funding restored and operations continue, but we can’t rule out future attempts to cut the budget or even derail the program entirely. In the realm of technology, WFIRST may prove the easier of the two missions to complete, as this story in Nature points out:

JWST and WFIRST are very different technologically, says Jon Morse, chief executive of Boldly Go Institute, a space-exploration organization in New York City, and former head of NASA’s astrophysics division. JWST involves complex designs that have never been tested before, such as the enormous sunshield. WFIRST will use a well-understood 2.4-metre mirror design that does not require lots of new technology.

“WFIRST is not likely to develop the cost problems of the same magnitude as JWST,” Morse says.

Assuming its operations budget isn’t too severely raided to pay for JWST’s extra costs. By comparison, WFIRST’s own budget cap is a relatively svelte $3.2 billion.

See here as to what it will take to deploy JWST in space and you will better appreciate the satellite’s current situation:

https://www.forbes.com/sites/startswithabang/2018/01/26/how-the-james-webb-space-telescope-will-deploy-in-an-ideal-world/#5ab8a6296791

What a long, frustrating story with JWST. This suggests deep problems within NASA. Either the technology itself was not ready for implementation (i.e. a step too far), or the institution has failed to remain financially responsible and viable. Would Elon Musk and his company have taken as long and spent this much money? How many under-utilized senior engineers with large pay checks does NASA continue to support?

Beware simple explanations for complex problems, especially when taking a swing at piñatas du jour. The private sector is very much embedded in this taxpayer project. And compared to the men and women publicly devoting their careers at NASA, fractionally transparent.

NASA should have abandoned the cost-plus system long ago. That’s the main problem.

Left only to fixed-price contracting, NASA would accomplish very little. As this issue shows, it’s nearly impossible to come up with a realistic cost and schedule estimate on an ambitious, complex project completely unlike anything that has ever been attempted before. If JWST were bid out as firm fixed-price, one of three things would have happened: 1) all the qualified contractors would no-bid, as the risks would have been enormous, 2) bids would have come in outrageously high, as they would need to cover all the possible anticipated development contingencies, or 3) *someone* would have won a bid deemed “reasonable,” and cost and schedule overruns would have happened anyway, except now they would threaten to bankrupt whatever company would have gotten the contract in the first place.

On the contrary, it’s due to the cost-plus system that they can’t come to realistic prices. SpaceX works with a fixed-cost system and it develops hardware very quickly and very cheaply. Also, if a company can’t deliver the contracted hardware, NASA loses no money at all.

See some examples of the cost-plus horror gallery: http://matus1976.com/read_books/zubrin_robert/entering_space/quotes.htm

See also what Musk thinks about cost-plus: https://arstechnica.com/science/2017/07/elon-musk-knows-whats-ailing-nasa-costly-contracting/

I have no idea who Jon Morse is nor why his opinion should be given particular weight here. However, to say, “WFIRST is not likely to develop the cost problems of the same magnitude as JWST” simply flies in the face of reality. WFIRST’s cost HAS exploded and seems set to expand further. By all my interest in WFIRST these cost overruns can endanger future projects that we may then as a result never see.

The coronograph could have been flight tested on a small mission. I just hope plans for LUVOIR aren’t being damaged by the Webb and WFIRST overruns.

I’m a huge supporter of JWST. And yeah, I know it’s big, and what it will be asked to do is without precedent. Still, I feel like a competent, properly managed team should have been able to build two with the time and the budget that has been used up. I have this picture that NASA finally got a big money project, and all the incumbent contracting vultures had to get their beaks wet in all that money. I don’t have any insider info on the project, but I can just tell that the money was divided on the patronage system, not by some meritocratic system.

NASA (and the government in general) really needs to reform its contracting system. Just publish clear outlines of what capabilities a new spacecraft (or weapons system, or whatever) should have, and how much this capability is worth to the government. Then only pay once the thing is up and doing science. Sure, for big projects they might make some cheap loan money available to the groups that are making progress.

So let’s say there were a $3 billion prize for digging up 20kg of Vesta and returning it to Earth. I firmly believe that bloated firms like Northrop would approach that project very differently from how they managed the JWST. I’m imagining their competitors would include a mad scramble of the world’s idle billionaires like Jeff Bezos and all those tycoons who buy soccer superteams to show they can outpiss the other billionaires. What they’re after is prestige and bragging rights, and winning the multibillion dollar space mining challenge would be a pretty epic thing to brag about.

The article says blithely “JWST will operate 1.5 million kilometers from Earth, meaning that servicing missions by astronauts like Hubble has received will not happen”, but I don’t think that’s an absolute given. Supposing that – the heavens forbid – a servicing mission, or a de-glitching mission, is required: it doesn’t seem beyond the wit of man for this to be a first test of the trans-lunar capabilities of the human race. OK, I know, there might be issues with the time-scale…

Repairing JWST sounds like a good medium-distance mission to extend our manned capabilities beyond Earth-moon space. Surely I can’t be the only one this has occurred to ? It would give us a backup option to repair JWST and also give us practice for taking humans a bit further than they have been before.

Can someone tell me why this is not an alluring target ?

OK — so why *can’t* humans be sent out to Webb to do a servicing mission? Is it somehow against the laws of physics, or something? Put a Dragon into LEO from an F9; fly another F9 payload into LEO — the workshack (so to speak). Dock ’em. Fly ’em out to the LaGrange point where Webb is supposed to be parked at. What’s the difficulty? (Other than cost of course…..) Better an actual human intervention in space than lose $9 billion bucks. We *know* how to do this sort of thing. “We can’t do anything to diddle with Webb after it’s launched.” Nonsense! Of COURSE we can!

Indeed. I imagine that both SLS and BFR can support a manned mission to L2. A good excuse to stretch the legs in any case!

Reporters and others may be stuck in the Space Shuttle era mindset where the vehicle fleet could not go any higher than various low Earth orbits.

Of course at the moment we do not have anything in place that I know of which could both reach JWST and repair it, but that needs to change. The satellite telescope is too important, too complex, and too expensive not to have some kind of measures in place for on-orbit repair. And it won’t be the only one, so such a need is certainly not a one-off.

Hey, what does the X-37B do exactly? Just wondering.

https://www.airspacemag.com/space/spaceplane-x-37-180957777/

Remember when NASA considered sending a robotic repair mission to the Hubble Space Telescope? I don’t know how far they ever got with those plans, but perhaps something could be adopted from that concept for a JWST repair mission.

Remember the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory (CGRO) launched from the Space Shuttle STS-37 mission in 1991? The satellite’s high gain antenna boom was stuck by an errant cable and nothing remotely or even with the Shuttle’s robotic arm could free it. An astronaut had to conduct an EVA to save the mission. And CGRO was simple compared to everything the JWST has to do to work right.

JWST will be on other side of Moon at L2, well beyond Shuttle or (speculatively) X-37 capability. This article https://www.space.com/3833-nasa-adds-docking-capability-space-observatory.html states JWST had a docking adapter installed (IDA) which means that there is at least something to dock to. A possibility could be Orion (crewed), but more likely would be some semi autonomous servicing spacecraft such as Orbital’s MEV/MRV. The latter might also or instead be able to refuel JWST with nascent satellite refueling capability being developed. Perhaps JWST designers considered this and scar’d some necessary features. The other Crewed vehicles in the works (SpaceX Crew Dragon and Boeing Starliner) probably don’t have the duration / capability for a mission to L2, as these are being designed for ferrying Crew to/from ISS in LEO. Hopefully we will have some options in the event JWST has a problem or to extend its usable life after so much has been spent.

Orbital ATK unveils new satellite-servicing technology

by Jim Sharkey

March 31, 2018

During the recent SATELLITE 2018 Conference and Expo, aerospace company Orbital ATK introduced two new in-orbit satellite servicing products: the Mission Robotic Vehicle (MRV) and Mission Extension pods (MEPS). These new products will join the company’s Mission Extension Vehicle (MEV) to create a suite of in-orbit satellite servicing technologies capable of extending the life of existing satellites.

The MEP is an external propulsion module that attaches to an aging satellite that is low on fuel and provides up to five years of additional life in orbit. Once installed, the MEP is controlled by the customer via a self-contained C or Ku band telemetry and command system.

The primary mission of the MRV spacecraft is to transport and install MEPs and other payloads to customer satellites. The MRV can also provide space robotic capabilities for in-orbit repairs and other functions. Orbital ATK’s SpaceLogistics subsidiary will operate the new system, with its launch currently scheduled for 2021.

Read more at:

http://www.spaceflightinsider.com/organizations/orbital-sciences-corp/orbital-atk-unveils-new-satellite-servicing-technology/

Musk is a different animal from government corporate contracts. Every penny out of Musk’s pocket is a penny less in his pocket. He can be expected to maintain ironfisted control over costs. Taxpayers’ money has to sustain government bureaucratic bloat, corporate corpulence, boards of directors benefits and bonuses and of course the shareholders’ portion.

How much of JWEST’s $8.8 billion is going for JWEST, and how much is being diverted? Would a consortium of billionaires tasked with JWEST put the funds to more effective use?

NASA is not in a good place, and has not been in one for a long long time…the gov’t paycheck and pension these folks receive has destroyed any serious and useful productivity we can expect as taxpayers. The years away Space Launch System is an embarrassment compared to the slightly less powerful (but real) reusable Falcon Heavy. For the price of one SLS in 2022 (or whenever these less than stellar rocket scientists get there stuff together) we could buy 4-6 Falcon Heavy…maybe more. Our gov’t should turn NASA into something akin to the NSF and let the private sector take over thru competitive ideas and bidding. Tranquility Base was a long time ago.

Here is an article by Elon Musk about his plans for Luna and especially Mars in the 2020s:

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/full/10.1089/space.2018.29013.emu

Musk anticipates a manned landing on Mars via SpaceX by 2024. I am wondering if NASA will even have its first SLS test – emphasis on the word test – by then, let alone any solid plans for our celestial neighbors. I do not say this either lightly or happily.

IBM used to be the undisputed king of the computer world. They still exist and are still respected for their legacy in making the computer age happen, but the technology and culture changed and they have lots of competition now. I think the same fate will happen with NASA unless it can make some radical changes and upgrades very soon.

ljk, I am sad as well when it comes to NASA and I just don’t get how and when they lost there Apollo mojo.

The culture changed radically starting in the 1960s. We also had the Vietnam War which drained money and resources from many places along with killing and injuring lots of people on both sides. Then add in President Richard Nixon who along with NASA Administrator James Fletcher killed any plans for a real working space station in Earth orbit, lunar bases, and manned missions to Mars.

We were left with the Space Shuttle, which was not only far overpriced and often left looking for a mission but even lacked the “romance” of earlier manned spacecraft projects, especially Apollo. NASA and the military tried to make the Shuttle the go-to space vessel and we saw what happened with that plan.

After all these decades I feel we are finally getting back on track in the direction we should have been going in space. A lot of this is thanks to commercial space enterprises. If NASA can continue to work together with them then it has a chance of staying relevant and useful.

We also need to keep in mind that there are other players in the international field who are quite ambitious about space. Leading that pack is China. Russia is trying to become a major contender again but we will see if they can overcome their corruption and often lax standards. India is the other space nation to watch out for, as they will likely be launching their own manned missions in a few years. I know there are others but these are the top three at the moment as far as I can see.

It now appears that SPHERE-ESPRESSO will have definitive information on the phased lightcurve of Proxima b BEFORE JWST has,

Paul Gilster: This just up on the CURRENT ESO blog “Shooting for the Stars”. Upgrades to the Very Large Telescope instrument, VLT Imager and Spectrometer for Mid- Infrared(VISR) that would make it capable of IMAGING a habitable SUPER EARTH planet orbiting EITHER Alpha Centauri A OR Alpha Centauri B with just 100 hours of observing time are being made RIGHT NOW, and will be done by MID 2019, whereupon an observing campaign will commence IMMEDIATELY THEREAFTER and will be completed in two weeks time!!! PLEASE CHECK THIS OUT!!!

ESOblog link for March 23, 2018 here:

http://www.hq.eso.org/public/blog/shooting-for-the-stars/

What you’ll discover in this blog post:

•What the Breakthrough Initiatives are

•How ESO is upgrading the VLT to search for habitable planets in the Alpha Centauri system

•The challenges of searching for exoplanets

5 Reasons Why Astronomy Is Better From The Ground Than In Space.

https://medium.com/starts-with-a-bang/5-reasons-why-astronomy-is-better-from-the-ground-than-in-space-a252c1c54b3c

Remember the Trappist 1 system was discovered by a 24 inch – 60 centimeter telescope, that you can buy on the open market for less then $100,000.00 complete!

Some interesting articles that may have resulted in Lockheed’s experimental, telescope-shrinking SPIDER. These cameras would be great for real time wide field surveys for exoplanets. Could they out do

TESS??? From a high altitude site maybe!

GIGAPIXEL CAMERA SEES FAR MORE THAN MEETS THE EYE.

https://www.wired.com/2012/06/gigapixel-camera/

50-gigapixel camera is straight out of science fiction.

https://www.nbcnews.com/technology/futureoftech/50-gigapixel-camera-straight-out-science-fiction-840003

AWARE2 Multiscale Gigapixel Camera.

http://disp.duke.edu/projects/AWARE/

http://www.gigapan.com/galleries/10845/gigapans

Aqueti – Aqueti’s 100-megapixel scale, multi-lens Mantis systems offer a compact, integrated solution that reinvents array cameras.

https://www.aqueti.com/

Gigapixel Computational Imaging.

http://www.cs.columbia.edu/CAVE/projects/gigapixel/

First images from Lockheed’s experimental, telescope-shrinking SPIDER. (Segmented Planar Imaging Detector for Electro-Optical Reconnaissance)

“These images are combined using the principle of interferometry. This is where the light waves from the array images interferes with one another, and by analyzing the amplitude and phase of the interference patterns, a processor can generate a new image of much higher resolution.”

https://newatlas.com/spider-telescope-lockheed-martin/41403/

https://newatlas.com/lockheed-martin-spider-first-images/50755/

Could Future Telescopes Do Without the Mirror?

Read more at https://www.airspacemag.com/space/Hubble-Dinner-Plate-180967711

The way things are going METIS on the E-ELT will give us Proxima b data first ! I agree with those who say that NASA’s biggest error was in hugely underestimating the big technological leap to produce both a deployable telescope design and the various other supporting elements required of any large high precision space telescope . A perennial problem inherent to many previous envelope pushing engineering programmes .

I would be inclined to think this has contributed most to the problems throughout development with no surprise that more have occurred as the final round of intensive operational testing has been undergone . This far more than any negligence of the prime contractor .

The two biggest drivers of all have been the lack of a sufficiently large launch vehicle at time of conception which led to the deployable design to try and get the biggest possible scope into space . This as opposed to a conventional , much simpler ( and robust ) Hubble like ( and WFIRST) monolithic mirror telescope . The second driver was the absolute requirement for uber stability to allowing the precision pointing necessary to operate the telescope successfully. Micro thrusters are necessary to achieve this in addition reaction wheels , and they are obviously tricky to perfect . Even more essential really as any future large telescope , deployable, monolithic or whatever will require these as a sine qua non. The heat shield cracks I suppose should have been anticipated given the hugely increased size from anything that went before and the fact that unlike a monolithic scope the deployable JWST requires this to be a separate structure not braced by the telescope assembly proper . And lightweight too given the launch mass limitations .

Something else that hasn’t been commented on in this latest imbroglio , and not a new issue ,mis the fact that JWST has an incredible 168 moving parts , itself inherently risky as moving parts and space don’t mix well. That has always been the case and if not an immediate problem could easily become one after operation . I remember seeing a presentation by the Gaia PI , after its successful deployment and he couldn’t hide how anxious his team had been during the deployment process , something he obviously saw as pivotal in terms of risk. Gaia has far fewer moving parts than JWST. He even wryly offered best wishes to the JWST team about this mission element extemporaneously !

I think WFIRST will survive in some form or other and although it’s costs will climb it’s much simpler and smaller monolithic ( essentially Hubble) design won’t lead to as many unexpected technological though it too will require precision pointing and micro thrusters. So any additional cost of this with JWST will atleast not be a financial burden for WFIRST so much as a trail blazer.

Jon Morse is a universally respected former Director of NASA’s Astrophysics Division – so an informed observer . BoldlyGo Have done extensive development of their own independent 1.8m exoplanet space telescope concept involving many of NASA’s experts .

If you look at the projected NASA expediture costs they assumed a rapid drop off after 2019 for JWST reflecting its assumed completion and launch . This will all now be pushed back several years as most likely will WFIRST’s launch date .( quite literally a hostage of fortune, or lack of it !)

In terms of LUVOIR/ ATLAST / HDST, I wouldn’t be floating the concept about Washington at present ! I’m no politician but even I would blanch at such mention given what has happened . Longer term I do think that the biggest casualty to come out of this will be the deployable ( spell check brought up ” deplorable” which wouldn’t be far wrong either ) design. Even if it does eventually work if enough money is thrown at the problem the technological climate has now changed .

The imminent advent of New Glenn, SLS and BFR offers launchers with the payload fairing size and power to now launch large monolithic telescopes . Even the high cost of SLS launches pales into insignificance beside the costs of a deployable scope – the commercial launchers are a snip and in BFR’s case , bigger. Even optimistically no LUVOIR is going to launch before the mid 2030s aomsomebirball of these rockets will be fully operational.

Another corollary of big, cheap commercial launchers ( bringing in the Falcon Heavy here too) is that they would now bring the option of modular in orbit assembly telescope designs into economic play. NASA have several such designs fairly well worked up – the best of which is similar ,12m space version to the “Colossus ” telescope . Like that telescope it also becomes operational incrementally long before completion and if assembled in accessible LEO any bugs can be ironed out during construction and before deployment .

I don’t think we will be seeing a LUVOIR anytime soon though and it will be interesting as to where current events leave the Science Definition team work currently being done on this ahead if the 2020 Decadel. The biggest threat is likely to come from the welcome return of US manned space flight . Short term .Even here though , how many more manned (cis) lunar missions are really needed ? Mars remains in my opinion an elusive goal even medium term. So there will need to be things found for manned space flight post the ISS so this may yet be LUVOIR’s saviour too .

I think it best to launch the JWT when we have man rated trans lunar capacity again. this would give nasa more time to integrate and test the telescope, and provide an insurance against an upset during deployment, or unexpected early parts failure.

The idea of a deployable scope like JWST was spawned from the lack of a larger EELV at its time of conception. Delays throughout have been driven by the need to drive a large , square telescope shaped peg into a small , round payload faring shaoer hole. And it’s been banged in we’ll and truly whatever the risk, cost and image. To where we now find it. The imminent advent of large, cheap commercial EELVs and cis lunar manned space flight , plus improved robotics now ones the door to LEO in orbit assembly . Breckenridge Associates have been working on an Evolvabke Space Telescope which incrementally constructed in situ over five launches of say a Falcon Heavy , building from an initial ( operational) 4m Hab-Ex format all the way up to a 14-20m fill LUVOIR telescope. This was published in SPIE last September possibly even anticipating a further JWST delay and the maiden Falcin Heavy flight . And commercial manned space flight possibly starting later in 2018 too.

Built out of 4m hexagonal segments , with a rigid , non deployable heat shield and propulsion system/ satellite bus bolted on . Linking the phase construction with NASA’s Decadel space telescope definition work was clever too.No lightweight ,flimsy or numerous parts required as with the JWST.

The principle of LEO assembly has already been well established with the ISS , though with no real regard for cost in that instance in an age when the space shuttle was used. The economic situation has now changed and opened up the possibility of LEO construction again. Cost can be stretched out over time , something that could ease the strain pon Nasa.’s JWST beleaguered finances. But any telescope would be operational from phase 1 all the all through to completion.

Management Shake Up on Webb Space Telescope, AGAIN! – this is getting really old!

NASA Announces Senior Leadership Changes to Refocus Launch Readiness Efforts for Webb Telescope.

http://spaceref.com/news/viewsr.html?pid=51280

http://spaceref.com/news/viewpr.html?pid=52444

NASA Announces Independent Review Board Members for James Webb Space Telescope

Press Release From: NASA HQ

Posted: Monday, April 9, 2018

NASA has assembled members of an external Independent Review Board for the agency’s James Webb Space Telescope. The board will evaluate a wide range of factors influencing Webb’s mission success and reinforce the agency’s approach to completing the final integration and testing phase, launch campaign, and commissioning for NASA’s next flagship space science observatory.

“We are exploring every aspect of Webb’s final testing and integration to ensure a successful mission, delivering on its scientific promise,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, Associate Administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. “This board’s input will provide a higher level of confidence in the estimated time needed to successfully complete the highly complex tasks ahead before NASA defines a specific launch time frame.”

The board, convened by NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, includes individuals with extensive experience in program and project management, schedule and cost management, systems engineering, and the integration and testing of large and complex space systems, including systems with science instrumentation, unique flight hardware, and science objectives similar to Webb.

The Independent Review Board review process will take approximately eight weeks. Once the review concludes, the board members will deliver a presentation and final report to NASA outlining their findings and recommendations, which are expected to complement recent data input from Webb’s Standing Review Board. NASA will review those findings and then provide its assessment in a report to Congress at the end of June. Northrop Grumman Aerospace Systems, the project’s observatory contractor, will proceed with the remaining integration and testing phase prior to launch.

JWST was supposed to launch this year. At least they didn’t cancel it – yet.

https://www.nasa.gov/press-release/nasa-completes-webb-telescope-review-commits-to-launch-in-early-2021

Well, whenever JWST is finally launched and working, it will be examining Jupiter’s Great Red Spot:

http://www.spaceflightinsider.com/missions/space-observatories/james-webb-space-telescope-to-study-jupiters-great-red-spot/

To quote:

According to NASA, the researchers hope infrared observations will provide insight into the Great Red Spot’s unique color, which some scientists believe is produced by the interaction of solar radiation with chemicals, including sulfur, nitrogen, and phosphorus, originating deep within the storm and brought to its upper layers by atmospheric currents.

“We’ll be looking for signatures of any chemical compounds that are unique to the [Great Red Spot]…which could be responsible for the red chromophores,” Fletcher said. “If we don’t see any unexpected chemistry or aerosol signatures…then the mystery of that red color remains unresolved.”

According to NASA, chromophores are the parts of molecules that give them their colors.

JWST could potentially solve another mystery, specifically the unexplained heat of Jupiter’s upper atmosphere in the vicinity of the Great Red Spot. According to NASA, one theory is that heat is generated in the storm’s interior and is transported from there to the planet’s upper atmosphere. Specifically, Fletcher wants to test a proposed theory that attributes heat within the Great Red Spot to colliding gravity waves and sound waves produced by the storm.

And this…

http://www.spaceflightinsider.com/missions/space-observatories/jwst-exceeds-cost-cap-launch-delayed-to-2021/

Too big to fail?

NASA announced last week yet another delay for the James Webb Space Telescope as well as a cost increase that will require Congress to formally reauthorize the mission. Yet, as Jeff Foust notes, few doubt that the mission will continue even with its latest problems.

Monday, July 2, 2018

http://thespacereview.com/article/3526/1