I like nautical metaphors as applied to the stars, my favorite being the words attributed to Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, French writer/aviator and author of poetic works about flight like Wind, Sand and Stars (1939), and a work familiar to most American students of French, Vol de nuit, published in English as Night Flight (1931). I think the Saint-Exupéry quote captures what it takes to contemplate far voyaging:

“If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up the men to gather wood, divide the work and give orders. Instead, teach them to yearn for the vast and endless sea.”

Image: Antoine de Saint-Exupery, whose work inspired, among many other things, my own decision to take up flying.

I had to track down the quote because the last time it appeared in these pages, a reader wrote to tell me he had never found it in Saint-Exupéry. I hadn’t either, which bothered me because I am a huge fan of the man’s work. It certainly sounded like him. So I did some digging and turned up a passage in Saint-Exupéry’s posthumously published Citadelle (1948) that comes close. The quote above is a much abbreviated paraphrase but does capture the spirit of the original (you’ll find a translation of the original at the end of this post).

Looking out over the ocean is much like looking out into the stars, triggering that same sense of immensity and, among some at least, the drive to explore. I get the same triggering effect by looking at images from spacecraft missions, like the views below from the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), which has now provided us with a ‘first light’ look at the southern sky.

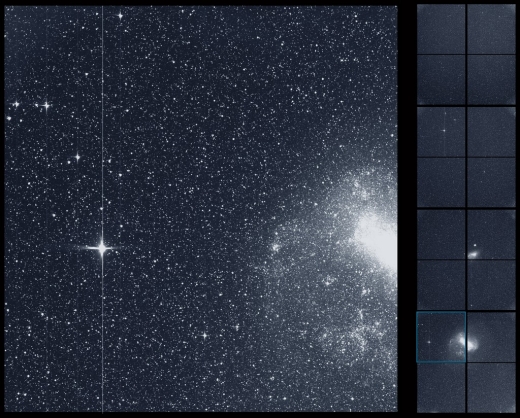

Image: The Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) took this snapshot of the Large Magellanic Cloud (right) and the bright star R Doradus (left) with just a single detector of one of its cameras on Tuesday, Aug. 7. The frame is part of a swath of the southern sky TESS captured in its “first light” science image as part of its initial round of data collection. Credit: NASA/MIT/TESS.

So do images of the stars make us yearn for deep space as Saint-Exupéry’s passage makes us yearn for the sea? I suspect so, and it would explain how often we resort to the sea in describing the stars. This morning I can point to Paul Hertz, who is astrophysics division director at NASA Headquarters, a man who likewise resorts to a maritime theme in describing what TESS will do:

“In a sea of stars brimming with new worlds, TESS is casting a wide net and will haul in a bounty of promising planets for further study. This first light science image shows the capabilities of TESS’ cameras, and shows that the mission will realize its incredible potential in our search for another Earth.”

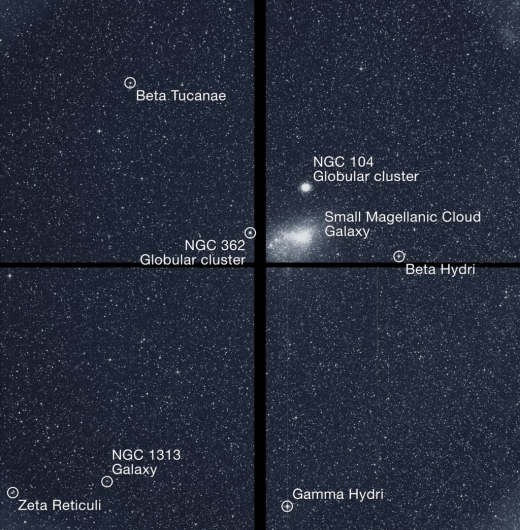

That bounty should reveal numerous nearby targets for the investigation of the James Webb Space Telescope as well as later space- and ground-based instruments. The full four-camera image that is shown below was captured on August 7, and took in constellations from Capricornus to Pictor, and both the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds. This view of the southern sky includes more than a dozen stars already known to have transiting planets.

Image: The Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) captured this strip of stars and galaxies in the southern sky during one 30-minute period on Tuesday, Aug. 7. Created by combining the view from all four of its cameras, this is TESS’ “first light,” from the first observing sector that will be used for identifying planets around other stars. Notable features in this swath of the southern sky include the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds and a globular cluster called NGC 104, also known as 47 Tucanae. The brightest stars in the image, Beta Gruis and R Doradus, saturated an entire column of camera detector pixels on the satellite’s second and fourth cameras. Credits: NASA/MIT/TESS.

Whereas the Kepler mission ‘stared’ at a single field of stars at distances up to 3,000 light years, TESS puts the same transit detection strategy to work on much closer targets, 30 to 300 light years away, and up to 100 times brighter. The spacecraft will monitor 26 sectors of the sky for 27 days each, ultimately covering 85 percent of the sky, with the first year of operations dedicated to southern stars before beginning the second year-long survey of the northern sky.

The science investigations will include those requested through the TESS Guest Investigator Program, which allows the scientific community at large to use the spacecraft for research.

“We were very pleased with the number of guest investigator proposals we received, and we competitively selected programs for a wide range of science investigations, from studying distant active galaxies to asteroids in our own solar system,” said Padi Boyd, TESS project scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “And of course, lots of exciting exoplanet and star proposals as well. The science community are chomping at the bit to see the amazing data that TESS will produce and the exciting science discoveries for exoplanets and beyond.”

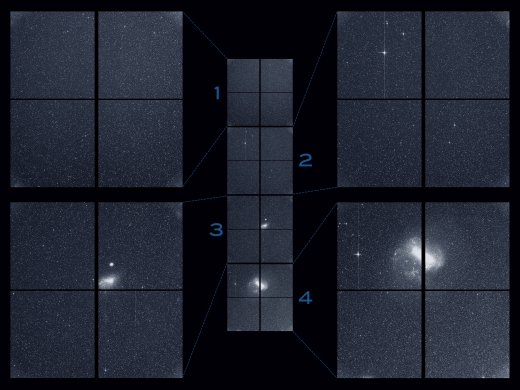

Here’s a square from the third camera; note the Small Magellanic Cloud just right of center.

Image: The Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) captured this square of stars and galaxies in the southern sky with its third camera during one 30-minute period on Tuesday, Aug. 7. Bright objects are labeled. Credit: NASA/MIT/TESS.

A sea of stars indeed, with the TESS targets bright enough for high-grade spectroscopic follow-up. All of this is coming together as part of the extension of our studies to the atmospheres of small, rocky worlds. Yesterday we looked at a paper from Anthony Del Genio et. al. on Proxima Centauri b. The Del Genio paper makes the point that “The population of potentially habitable rocky exoplanets in M star systems has now suddenly reached the point at which it will soon be possible to assess the demographics of this class of planet.”

Exoplanet demographics! We’ve come so far since the first detection of planets around a main sequence star back in 1995. TESS will be a huge part of extending our catalog.

And returning to the Saint-Exupéry passage with which I opened, here is a translation of the passage in La Citadelle that I found online.

One will weave the canvas; another will fell a tree by the light of his ax. Yet another will forge nails, and there will be others who observe the stars to learn how to navigate. And yet all will be as one. Building a boat isn’t about weaving canvas, forging nails, or reading the sky. It’s about giving a shared taste for the sea…

Good stuff, but I admit to liking the abbreviated version better. It has more punch.

Today’s arXiv brings the first TESS planet: a short-period sub-Neptune around the star ? Mensae, already known to host a superjovian in an eccentric orbit.

And here’s another one, a planet slightly larger than Earth in an 11-hour orbit around a nearby red dwarf: Vanderspek et al. (arXiv:1809.07242 [astro-ph.EP]) “TESS Discovery of an ultra-short-period planet around the nearby M dwarf LHS 3844“

Paul says “So do images of the stars make us yearn for deep space as Saint-Exupéry’s passage makes us yearn for the sea? I suspect so…”

Or as another and greater writer and thinker put it:

Gully Foyle is my name

And Terra is my nation

Deep space is my dwelling place

The stars my destination.

(Alfred Bester)

Regarding TESS results, one point is usually overlooked which I believe deserves emphasis. TESS will uncover a huge number of new candidate exoplanets but due to the satellite’s short orbital period, many of the detected transits will be singular in nature. It is planned that ground observatories will confirm the TOI’s and determine their orbital period. TESS has a Candidate Target List which encompasses 10.8 Million stellar systems. It is likely that around 1 in 200 will be oriented edge on to us allowing transit observations. Thus tens of thousands of TOIs may be registered but without reliable periodicity data. Each TOI must then be INDIVIDUALLY confirmed from the ground. This represents an unimaginable mass of observing time. In reality it is not achievable. Some sort of selection will be undertaken and priorities set as to which TOIs deserve most attention.

Less an embarrassment of riches it is more a burden. In the earliest days of planning TESS was conceived on a longer orbit. Although this may have resulted in a smaller fraction of the sky being covered over the course of TESS’s mission, it would have brought a massive reduction of burden to the Earth based telescopes which after all also have a full plate of nonexoplanetary observations to do.

Babes in TOIland!

We are in the golden age of exploration! TESS is to have a lifetime of some 20 years so it should be going into a much more in-depth look after the first two year survey. Hopefully that will bring planets in as high as ten year orbits and with some of the new algorithms and new technics it will be easier to follow up from the ground. A good example is of the Vulcan planet by the Dharma Planet Survey around 40 Eridani A useing smaller scopes.

The thrusters work better than planned, so it MAY go FIFTY!

Dare I say that searching for exoplanets should be a high priority for professional astronomers these days? We know they exist and we have confirmed thousands of them with the insight that there may be more alien planets than stars in the Milky Way galaxy alone.

Add in that little possibility they may be inhabited or at least inhabitable and I say we have a very good reason for astronomers to shift their attention and resources to finding alien worlds.

It isn’t so much yearning for the sea as discovering the wonders of far shores. When I was young, we did not know if the stars had “far shores” to visit. Now we know that planets are in abundance, and we yearn to visit them.

Our galaxy alone will have more planets to visit than there are places on Earth to explore, enough to fill many human lifetimes. There will be worlds that are off limits except for minimal footprint visits and others that will be a blank canvas to build new [post-]human-centric worlds.

Well they just found Vulcan…

http://news.ufl.edu/articles/2018/09/exploring-strange-new-worlds-star-trek-planet-vulcan-found.php

With those specs, I’m surprised Spock wasn’t a short, dumpy looking fellow, with massive muscles. It would, however, explain his strength compared to Earthlings.

It all depends on which VERSION of Vulcan. The TV version is actually part of a BINARY PLANET SYSTEM(the other planet is lifeless and named Calaban, spelled slightly different from Caliban, the Atrades homeworld in the “Dune” series). Both planets are of equal size and mass(how convenient)and Calaban eclipses of 40 Eradani A keep Vulcan cool enough(relatively speaking)to prevent it from being trapped in a runaway greenhouse. The movie version is a single planet where. in the not-too-distant future, astronomers on Earth will be able to witness its total destruction.

I stand corrected. Apparently there are THREE(one TV, and TWO movie)versions! The “Star Trek-The Motion Picture” version of ljk’s below link has the other planet(equal mass but smaller size) as “T Krut”. I guess only the reboot movies have Vulcan as a single planet.

This article claims that some ETI(s) persone from “40 Eridani A” was involved in “Star Track” screenplay creation :-)

Fun.

From Memory Alpha, the Star Trek reference site:

http://memory-alpha.wikia.com/wiki/40_Eridani_A

To quote:

In 1991, Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry, along with three scientists from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, endorsed 40 Eridani A as Vulcan’s primary (rather than Epsilon Eridani, which is occasionally misidentified as Vulcan’s primary) stating, in part: “We prefer the identification of 40 Eridani as Vulcan’s sun because of what we have learned about both stars at Mount Wilson … based on the history of life on Earth, life on any planet around Epsilon Eridani would not have had time to evolve beyond the level of bacteria. On the other hand, an intelligent civilization could have evolved over the aeons on a planet circling 40 Eridani. So the latter is the more likely Vulcan sun.”

I also found an artist’s representation of the system:

http://trek-ts.org/NEW/Starfleet/Science/Astronavigation/Cartes/Carte_Systeme_Vulcain.jpg

If that’s Vulcan, then Spock looks suspiciously bipedal for a member of a species that either evolved floating in the atmosphere or swimming in the deep hot superionic oceans of a sub-Neptune planet.

Regarding the system, 40 Eridani B was the first discovered white dwarf star, so the system would have been affected by the evolution of the progenitor star through its giant phase. This raises the question of what the effects would be at 40 Eridani A, including the possibility of second-generation planet formation from matter ejected by the progenitor star.

Vulcan was the exception, but it is amazing how many alien worlds on Star Trek bore a more than casual resemblance to Southern California. :^)

The more we learn, the more surprised we are at how much we were ignorant of, and at how much more there may be in the “known unknowns” and even more so in the “unknown unknowns”. Seeking far and wide is the way to awareness of the expanse of that ignorance; filling in details in small sections will suggest its depth.

Expansion of its range follows from replication as a biological imperative: it is limited by habitat availability for species adapted to particular niches, while others may extend their range further. Humans can carry their habitat with them, although this too has limits, most notably those imposed by the sheer vastness of the cosmos.

Hi Paul,

Seeing your comment that “we’ve come so far”… I think it would be really interesting to someday see a post from you, with so much experience, to reflect upon how far we’ve come just in the past 10 years or however long, and how this seems like quite an exciting time… from the breakthrough initiatives to all the exoplanet projects now online or upcoming to something I rarely see mentioned on Centauri Dreams but even all the private sector projects when it comes to things such as rocketry. Although I read your posts daily, I think it would be great if someone out there just sort of summarized or laid out all the big things going on or all the things in the pipeline being constructed or perhaps proposed but actually might have some funding. For some, it might be hard to track it all. Just a thought!

I like the idea, Marc. Let me ponder and see what I can do with it. Thanks!

The Large and Small Magellanic Clouds may once have had a third member:

http://spaceref.com/astronomy/magellanic-clouds-due-may-have-been-a-trio.html

TESS now, ESPRESSO very soon. The first ESPRESSO planets could be made public by the end of the year. I expect DOZENS of sub-earth mass non-transiting ultra short period planets to be the BULK of ESPRESSO’s first results.

Am I right that the radial velocity measurements ESPRESSO uses for detection work best when we are viewing the system edge on, just as with the transiting method? It seems that if we are viewing the other system “from above” (or below, relative to that system’s plane), there would be no change in the star’s radial velocity (i.e. towards or from us). Instead the star would change its position relative to a fixed background. So while not as sensitive to orientation as the transit method, ESPERESSO will still rely on orientation to a degree?

Yes. You might find this illuminating: https://www.uio.no/studier/emner/matnat/astro/AST1100/h08/undervisningsmateriale/lecture3.pdf

Great news for the detection of planets in systems edge-on to us. I would love to know what missions/surveys are planned that would help to detect the other 99.5% of exoplanets… I understand the transit method is currently best in terms of raw numbers of planets discovered, and we can extrapolate the likelihood of planets around any star from the results, but of course very many of the exoplanets discovered are very far away. Is there some near-future planned iteration of one of the “wobbling” methods (Doppler or astrometry depending on whether the wobble is towards/from us or in the plane of vision) that would allow us to do a comprehensive survey of *all* the nearest stars for planetary systems, whatever their orientation? This would be more exciting to me than getting large numbers of transiting planets, in absolute terms, but missing almost all of the nearby systems.

Gaia should be coming up with some results:

“Measure the orbits and inclinations of a thousand extrasolar planets accurately, determining their true mass using astrometric planet detection methods.”

ASTROMETRY

“Using Gaia’s microarcsecond-precision to measure stellar positions, planetary systems are discovered through the wobble they introduce in the parent star’s position. This astrometry method is suitable for detecting long-period planets, but requires precise measurements and long time spans.”

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry also wrote space fiction, also being famous for the 1943 novella “The Little Prince” (see: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Little_Prince ). His home, the asteroid B 612, was even immortalized in a sculpture (a link to a photograph of it, at “The Museum of The Little Prince in Hakone” [see: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Museum_of_The_Little_Prince_in_Hakone ], is in the first above-linked article), and:

The French Canadian author Suzanne Martel (see: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Suzanne_Martel ), who in 1963 wrote the science fiction novel “Quatre Montréalais en l’an 3000” (published in English as “The City Under Ground”), portrayed a post-nuclear apocalypse technological civilization that grew from the survivors who occupied a large shelter inside Mont Royal (Mount Royal), from which Montreal got its name. One of the novel’s characters was named Eric 6 B 12, whose name might be an homage to the B 612, The Little Prince’s asteroid home.