Even today, I can well understand the reaction that Dennis Conti had when confronted with the prospect of finding a planet around another star with nothing more than an amateur instrument. Conti, who founded and now chairs the Exoplanet Section of the American Association of Variable Star Observers, was a newcomer to the transit method just a few years ago. “I thought, there’s no way for someone with a backyard telescope to detect a planet going around a distant star,” he says, looking back from the vantage of one now immersed in such observations.

My boyhood 3-inch reflector was not a backyard instrument — too many trees back there. So it became a front-yard telescope. Absent the technological innovations of the past five decades, I could only imagine vast instruments for studying objects around other stars. The transit method in exoplanet detection was a long way off, but the idea of seeing not a planet itself but a change in starlight as the planet crossed the face of its host now seems intuitively obvious. It takes a good deal more than a 3-inch reflector to get into the game, but today’s more sophisticated amateur telescopes can definitely make a contribution, as Conti has demonstrated.

Consider: In 2016, Conti coordinated more than 40 amateur astronomers who would assist a professional scientist in characterizing the atmospheres of 15 different exoplanets. A year later, he would begin teaching a course in observing exoplanets through the AAVSO, one that has taught more than 120 students ranging from professional scientists to high-school teachers. His Practical Guide to Exoplanet Observing, now in its 4th revision, is in use in many countries.

The AAVSO is now building its own Exoplanet Database, a useful entry into the field because the increasing amount of data gathered by amateurs should have a unified home. Many existing databases are built around specific space missions or ground-based surveys. The AAVSO’s entry will be a place where amateur astronomers can archive their exoplanet transit observations to make them available to the broader community. Long-term archiving of observations may turn up interesting features in lightcurves like transit timing variations, that could potentially identify the presence of a second planet in the same observed system.

Image: This artist’s concept shows the Kepler-444 planetary system, in which five small planets orbit a distant star. These five planets were detected by the transit method, which involves recording the periodic dimming of a star as a planet transits across its face. Amateur astronomers have been using the same technique to successfully and accurately detect exoplanets for more than a decade, and their observations can now be recorded in the AAVSO’s Exoplanet Database. There, they can be archived long-term and used by professionals and other amateurs to build scientific knowledge of interesting planets. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/AMES/Univ. of Birmingham.

I never followed up with larger home telescopes of my own, but I admire the dedicated amateurs who have plunged into this work. The synergy between amateur and professional can be productive. With TESS (Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite) now in operation, we’re reminded that thousands of exoplanet candidates are going to turn up in the next two years. Follow-up observations on the TESS candidates are to be submitted to NASA. The TESS Follow-Up Observing Program is coordinating its efforts with the AAVSO and has adopted its guidelines for best practices, as noted in this AAVSO news release.

“This emphasizes the value that nonprofessionals bring to the field of science,” says Stella Kafka, Ph.D., AAVSO Executive Officer. “People with moderate means can contribute from the ground to the knowledge base of the community. In principle, one can see the AAVSO as an international collaboration between professional and non-professional astronomers, working together to understand some of the most exciting phenomena in the universe.”

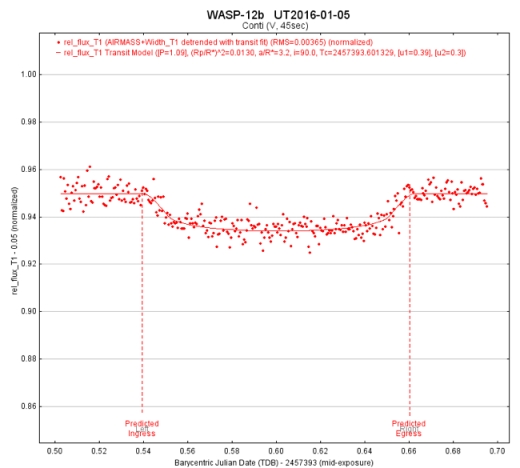

Image: The light curve shown here records the dimming of the exoplanet WASP-12b, taken Jan. 5, 2016, by Dennis Conti, Ph.D., founder and chair of the AAVSO’s Exoplanet Section. Conti used equipment available to amateur astronomers and compared his results to published data to show that he was able to successfully and accurately detect the exoplanet. The AAVSO’s Exoplanet Database will provide a place for amateur astronomers following established procedures to make their exoplanet transit observations available to the broader community of researchers, and to have their data archived long-term. Credit: Dennis Conti.

Many eyes on target with a wide range of instruments are better than a few, and bear in mind that observing an exoplanet transit from different locations and times can help astronomers assemble data on a complete transit that might otherwise be lacking. I’ll also remind non-astronomers with a passion to contribute of the Planet Hunters site, where participants can look at exoplanet data and sort through lightcurves from the Kepler mission. The ways for amateurs to make a contribution to exoplanet science are multiplying.

The Czech Astronomical Society as been for some years compiling exoplanet transit data and light curves. See

http://var2.astro.cz/EN/

Perhaps AAVSO might set up a small prize or other recognition for the first amateur or professional individual or team to identify life and the first to identify intelligence elsewhere. In spite of the fact that a Nobel committee might also evince an interest.

If the AAVSO is truly interested in keeping its numbers up, they will go with this angle. Today’s generation is not like any other thanks to the Internet and other social media devices. These venerable institutions need to recognize this.

Wonderful idea Robin. A modest prize for providing data for any new exoplanet discovery would also be very worthwhile. A tall order to identify life or intelligence elsewhere at present I would think but who knows what the capabilities of amateur astronomers will be in the future? Kudos to you for the idea.

With the estimates of the numbers of yet-to-be-discovered exoplanets, prudence would dictate that the prize for each new exoplanet would necessarily be just as constrained in its modesty.

What type of home telescopes are we talking about? Anyone have an idea of what specific products are being used?

Do Amateur astronomers can eliminate influence of Earth’s atmosphere on their star’s “dimming” measurements?

I hardly beleive that , or it should be “amateur” that own professional extra class observatory in perfect location (from astronomical point of view).

Atmospheric variations are on the order of milliseconds versus hours for transits. This can be accommodated by longer integration times, which in case would be routine for photographing faint objects. There are other precautions needed, such as no nearby objects of similar or greater magnitude so that integration can accumulate an area of pixels centered on the star. Longer term variations such as upper atmosphere haze can be calibrated out with a nearby non-variable star.

Although technically challenging there are many amateurs with the requisite skill and equipment. However they will be limited in comparison to larger and better equipment in well located observatories.

Athmosphere disturbances can last number of days, period very compatable with some discovered M dwarf planets. I understand that planet’s orbit movement has stable period relatively to mostly stochastic weather changes, but acconting amateur observatory limitations it can ruin all observations.

I can accept your arguments, I must to conclude – if our atmosphere is not the problem for astronomy – there was no need to spend money for Kepler, Tess etc. missions… (I do not agree with this point)

By the way I am wandering too: when looking at those nice “planet” transition graph) can amateur astronomer distinguish some double close located stars, from star + planet system? I am afraid he can’t do that at least looking this nice graph that we see in article.

May it will be possible to connect this graph to the planet transition if you know in advance that there should be planet with predefined period , the planet that was found by other more reliable astronomical instruments.

Your points about ground observations are valid. However there is a great deal that we can now do to improve the reliability and accuracy of observations using surface instruments. It is not a substitute for space-based instruments!

The point is that the more we can accomplish on Earth the less demand there will be for space instruments, which are terribly expensive and limited. This frees them up for observations that can only be done in space, and allows planning for instruments that are not redundant with what can be done in other ways.

Since much of the technology to reduce the error bars of ground observations is software and moderately priced hardware there is tremendous opportunity for motivated amateurs to make valuable contributions. Where necessary their findings can be followed up by professionals with better equipment and even to justify use of space resources.

This is not a binary choice between amateur/pro or ground/space. It’s about being able to do more and better observations without additional expense or effort. Technology advancements make it possible. This is good!

I am not against amateur astronomy and planet discovery in any way, opposite, I respect amateur astronomers :-)

I only want that information will be more correct, better do not primise “rivers of milk and honey”, to escape possible disappointment and as sequence lost of interest to astronomy.

I am sure that present time the exo-planet hunting is out of possibility , even for good equippet amateur astronomer.

Meanwhile we have reports about exoplanets from very serious astronomic tools, far ahead of advanced amateur level.

The American Association of Variable Star Observers has been taking light curves for over a 100 years. This is one research that amateurs astronomers have done more work then the professionals. I think they know what and how to do it correctly and the large scopes are short on time. So you should not belittle them!

Can you give me one example of this your formulas?

Sisyphus is well known persone who make much more work than anyone other on the Earth :-)