While compiling materials for a book on Apollo 11, Neil McAleer accumulated a number of historical items that he passed along to me (thanks, Neil!), and I’m thinking that with the 50th anniversary of the first landing on the Moon approaching, now is the right time to publish several of these. Centauri Dreams has always focused on deep space and interstellar issues, but Apollo still carries the fire, representative of all human exploration into territories unknown. In the piece that follows, Neil talked to Al Jackson, a well known figure on this site, who as astronaut trainer on the Lunar Module Simulator (LMS) worked with Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin before Apollo 11 launched, along with other Apollo crews. McAleer finalized and synthesized the text, which I’ll follow with a piece Al wrote for Centauri Dreams back in 2012, as it fits with his reminiscences related to McAleer. I’ve also folded in some new material that Al sent me this morning.

by Al Jackson and Neil McAleer

In the fall of 2018, this writer began a correspondence with Al Jackson, a NASA Simulator Engineer and instructor for Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin for the Apollo 11 mission.

“We instructors spent two and a half years with Neil and Buzz—almost every day for the first 6 months of 1969 [before the historic launch in July]. In those years we instructors spent almost that much time with the Apollo 9,10,12,13 crews and backup crews.

“When we were working with Neil and Buzz … Neil was indeed a very quiet man but he was not all that taciturn. He was easy going and approachable. The film First Man seemed to imply Neil was quite glum in private, but I never got that impression; even if there were times when he was, I never saw it. The movie even made it seem Neil was a bit morose in private, another aspect that I never detected from seeing him at work almost every day.

“It’s odd that we instructors on the Lunar Module Simulator worked with Neil and Buzz almost every day for those two and a half years, but we never socialized with them. We even traveled with them to MIT and TRW and only saw them at the technical briefings.”

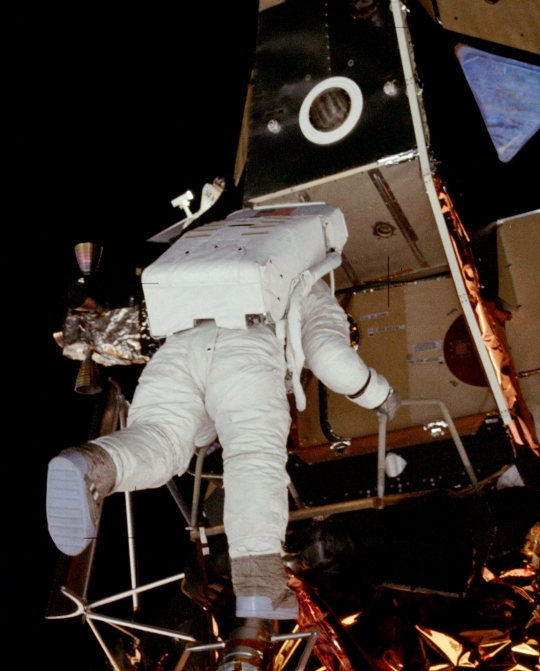

Image: Al Jackson (facing the camera at the main console of the Lunar Module Simulator) performing a checkout of LMS systems with his colleagues. Credit: A. A. Jackson.

“One thing— we really saw more of Buzz than Neil. Buzz was, and still is, a Space Cadet! He put in extra time on manual rendezvous training; he was responsible for the neutral buoyancy facility; and he practiced EVA for Gemini so he had zero problems on Gemini 12. Buzz was more into spaceflight than any of the other astronauts.”

A Working Team

In one of my emails to Al Jackson, I asked his opinion on how Neil and Buzz worked together during the simulator training years:

“My observation is that during training both Neil and Buzz got along fine. Funny thing, Buzz would definitely express himself more than Neil, but those two were the quietest we ever had in the cockpit during Lunar Module simulations.

“One time they were in at 8 am and did not say a word to us or each other by 11 am. I remember someone suggested we go up to the cockpit and check to see if they had passed out!

“I know an odd story about Neil,” Al continued. “One day he was in the simulator, came out, and smoked a cigarette, looked at us and said, ‘That was my one cigarette for the year.’ He smiled and went back to the cockpit.”

In a reply to Al, I gave him my opinion that this comment was similar to Neil’s well-known quote about every living human on our planet having a finite number of heartbeats in their lives, and Neil didn’t want to waste any of them on basic exercise when he loved to fly so much. This writer considers these two comments as Neil’s personal nods to human mortality.

Another story came in another e-mail from Al Jackson in early 2019: “I was talking recently to the main Primary Guidance and Navigation System instructor on the Lunar Module Simulator, Bob Force (Force and I spent a lot of time together); he noted that the day after the LLTV [Lunar Landing Training Vehicle] crash [May 6, 1968], Armstrong came to the simulator.

“We asked how he was, and he said, ‘Oh just some stiffness’—That was all.”

Armstrong had cheated death by about 2 seconds because his parachute opened just before he landed.

“I talked to another instructor who I met early that day, and he said something like ‘have a hard time yesterday?’ Neil, who had bitten his tongue during ejection gave that guy a very hard look.”

Image: Astronaut Neil Armstrong flying LLRV-1 at Ellington AFB shortly before the crash (left) and ejecting from the vehicle just seconds before it crashed (right). Credit: NASA.

Buzz Aldrin’s Exit from Eagle to Join Neil on the Moon’s Surface

As I was researching information about Apollo 11’s EVA and walk on the moon, one of my major sources was to read portions of the official transcript of their EVA activities. Here something unusual emerged. Aldrin’s real exit from the Eagle needed his crewmate’s specific directions on orientation of his body as he went through the hatch—just like Aldrin assisted Neil exiting the Eagle from inside its cockpit.

ARMSTRONG: “Okay. Your PLSS [Portable Life Support System] is—looks like it’s clearing. The shoes are about to come over the sill. Okay, now drop your PLSS down. There you go . . . About an inch clearance on top of your PLSS. . . .

Okay, you’re right at the edge of the porch. . . . Looks good.

ALDRIN: Now I want to back up and partially close the hatch, making sure not to lock it on my way out. [My italics for emphasis!]

ARMSTRONG: “A particularly good thought.”

Neil was probably thinking about the time of their EVA simulation “dress rehearsal,” when the mock LM’s hatch turned out to be locked when Neil unsuccessfully tried to re-enter their mock Lunar Module during rehearsal. He had to file a report. The lesson was learned.

So the answer is that they were both very aware of the possible problem on the “real EVA” for Apollo 11, and the lockout experience in training was avoided.

[PG: Al also adds this note in a morning email about the ‘locked hatch’ situation.]

“That was probably the egress – ingress simulator, which was a full sized mock-up of the LM (though there was more than 1 of those). It was a pretty faithful mock-up. I remember the very first day I worked at the Manned Space Center in Houston, the day I mustered in, which was the first Monday of the last week in January 1966… after work I climbed up in that simulator looked out the windows and thought of Wernher von Braun and Robert Heinlein, the men who , with their writings, had gotten me there! I felt like a space cadet!”

Image: “When it was my turn to back out, I remember the check list said to reach back and carefully close the hatch, being careful not to lock it,” said Buzz Aldrin, Apollo 11’s lunar module pilot. He climbed down the ladder, looked around and described the sparse lunar landscape as “magnificent desolation.” Credit: NASA/Neil Armstrong.

On Apollos 11 and 12

And this is Al Jackson’s article from 2012, one I reproduce here for its insights into the Apollo program.

I spent almost 4 years in the presence of Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin. I came to the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC) in 1966, where I was placed as a crew training instructor. I had degrees in math and physics at that time. Seems engineers were pressed into real engineering work or had been siphoned off into the DOD. Spaceflight attracted a lot of physicists who could be put to work on all kinds of stuff.

I met Buzz first, I think as early as 1966. At MSC in those days I used to be in Bldg. 4 (my office) or Bldg. 5 (the simulation facility) in the evenings. Sometimes we worked a lot of second shift and I was unmarried at the time with a lot of time on my hands. Anyway Buzz would come to Bldg. 5 to practice in a ‘part task’ trainer doing manual rendezvous, something he had pioneered. So I kind of got to know Buzz, but I can’t remember much but small talk and later talk about the Abort Guidance System which was my subsystem.

When the Lunar Module Simulator (LMS) got into operation I started seeing Neil, but never talked to him much. Of all the Apollo crews Neil and Buzz were the most quiet. I do remember Neil from the trips to MIT and TRW, to go to briefings on the Primary Guidance and Navigation and the Abort Guidance System.

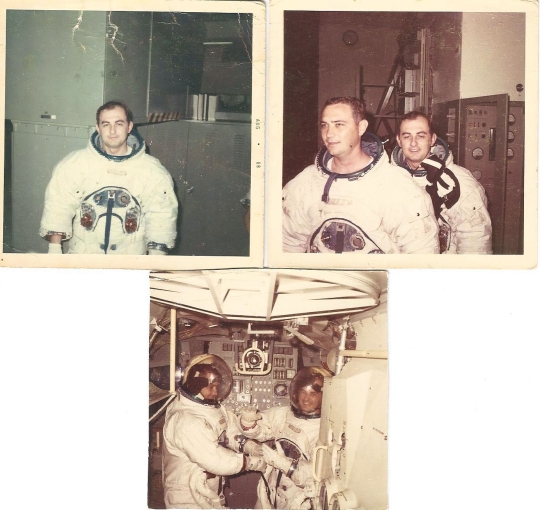

Image: Al Jackson (top left) and a NASA colleague testing the environmental system of the Lunar Module in 1968. Credit: Al Jackson.

I had seen Buzz do a little ‘chalk talking’ about technical stuff, but on the TRW trip Neil got up and gave a short seminar about rendezvous in orbit, some math stuff and all. He really knew his stuff. I remember being kind of surprised because I knew about Buzz’s doctorate in astronautics, but did not know Neil knew that much engineering physics.

The Apollo 11 crew were the backup crew for Apollo 8, except for Fred Haise — that crew too could have been first on the moon. I puzzle these days whether Deke Slayton and higher ups arranged that it would be Neil and Buzz or not. All the astronauts I worked with were very unusual and able men… but Neil and Buzz had more than the Right Stuff, they were kind of magicians of confidence. It would be years before the astronaut corps had anyone quite like them.

You know working Apollo, nearly 24 – 7 for five years, in those days we had our heads down in the trenches, so it is strange to think back, a lot of odd things and lore escaped my attention. I was never a diary keeper, but wish I had been. I do remember how seat-of-the-pants everything was. Everything became much more formalized in the Shuttle Era and I was glad I did not stay in crew training for all but 5 years of my tenure at JSC.

It was the Apollo 12 crew who were the most fun. Pete Conrad was the most free spirited man I ever met. He bubbled with enthusiasm and humor, a thinking man’s Evel Knievel. He was an ace pilot who kept us in stitches all the time. Conrad and Bean spent a lot of time in the LMS (I think Neil and Buzz spent the most) and we instructors really got tired of wearing our headsets , so when crews were in the LMS we would turn on the speakers we had on the console since the crew spent most of their time talking between themselves. When Conrad was in the cockpit we had to turn the speakers off, since we would unexpectedly have visitors come by.

The reason why: Conrad, an old Navy man, could string together some of the most creative blue language you would ever want to hear. The main guidance computer aboard both the Command Module and Lunar Module was called the Primary Guidance, Navigation and Control System (PGNCS), but the crews called it the PINGS. Conrad never called it that. I can’t repeat what he called it, but he never, in the simulator called it that. The instructors remembered the trouble Stafford and Cernan caused on Apollo 10 with their language, and we thought lord! Conrad is gonna make even Walter Cronkite explode in an oily cloud! Yet on Apollo 12 he never slipped once, that’s how bright a man he was.

A month or two before Apollo 11 Conrad and Bean were in the cockpit of the LMS and John Young was taking a turn at being the pilot in the CMS (Command Module Simulator). We were running an integrated sim. Young had learned that the CM would be named Columbia and the LM Eagle. Conrad being his usual individualistic self said that must have pleased Headquarters. (Of course Mission Control needed those names when the two vehicles were apart for comm reasons).

So Conrad could not resist. He told Bean and Young right then and there that they were going to name the CM and LM two names that I also can’t repeat. Bean and Young had a ball the rest of the sim giving those call signs, but that only lasted one day. Conrad, as you might suspect, never used the language in an insulting way or even to curse something — he was a very friendly and funny man. But it’s so second nature in the military to use language like that, and those Navy men, well, they never said “pardon my French!” Later the three Navy men (Conrad, Bean and Gordon) gave their spacecraft proper Navy names! Remember them?

[PG: I had to rack my brains on that one, but finally dredged up the command module’s name — Yankee Clipper. The LEM was Intrepid.]

Science Fiction and Apollo

[PG: Finally, this snip from another email Al sent me this morning, of interest to those of us who follow science fiction and its influence.]

“I have given interviews, by phone, to a few authors of recent Apollo 11 authors, I don’t know if it was Neil McAleer who asked me this question: ‘Did you meet any science fiction fans when you started at MSC in 1966.’ Somehow someone knew I had been in and still was (no longer in a strong way) in science fiction fandom. I said no. I did not meet any true blue fans in NASA till years later.

“About half the guys I worked with were avid SF readers, no surprise, but none had been in SF fandom.

“I did have one experience that Alan Andres, one of the authors of the new book Chasing The Moon, checked. In April of 1968 2001: A Space Odyssey had (I think) its 3rd USA premiere in Houston. I desperately wanted to see it opening night but was not able to wangle a ticket.

“I did see it the next night. The next week around the coffee pot in building 5 Buzz was there talking to the Apollo 11 backup crew Lovell, Anders, and Haise. They were asking him about the ending, I distinctly heard Aldrin telling them to read Clarke’s Childhood End. I was not surprised that Buzz was an SF reader. (Alan Andres told me that Buzz said he was tired from training that day and that he slept through most of the movie… still I think Buzz caught enough to know a good answer. I swear I heard this conversation in April of 1968. I am sure Buzz does not remember it).”

Image: A time like no other: Collins, Aldrin, Armstrong amidst an exultant crowd in August of 1969.

Great stuff, thanks. I read Aldrin’s “Encounter with Tiber”. He was coauthor with another writer. I loved it.

And I agree that reading Clarke is the best way to ‘grok’ the ending of 2001

A note: In those days there was two sets of training simulators a Command Module Simulator (CMS) and a Lunar Module Simulator (LMS) in Houston, there was also a CMS and LMS at the Cape. We Houston guys not only did training but also validation of the software before it was shipped to the Cape. We Apollo Simulator crews in Houston have always been miffed because whenever there was coverage the crews usually mentioned the Cape guys… to this day…. tho must say there is not a lot of mention of the CMS and LMS in Apollo 11 documentaries.

The moon landing is arguably the greatest achievement in the history of mankind. And as time stretches into the future, ever further away from that day in July 1969, the marvel of Apollo amazes more and more. That one step and giant leap coming as it did from a surprisingly primitive era marks the beginning of our expansion into the universe.

It’s with great gratitude and emotion that I celebrate the vision and dedication of an entire nation to achieve the goal of putting men on the moon and returning them safely to the Earth. Not just for America, nor for the good Earth of 1969, but for all future generations to remember and be inspired by.

I’m reminded of J.G. Ballard’s comment that the only human being whose name would be remembered in 50,000 years was Neil Armstrong. Be that as it may, I find the 50th anniversary deeply emotional as well, especially since it recalls all the feelings of landing day itself and seems to magnify them.

Having been a Space Cadet 1st Class in my youth and having recently visited the Kennedy Space Center, my appreciation of the Apollo program is to the moon. However, I would simply characterize Apollo as the greatest engineering achievement of the 20th century. Calling it the greatest event in human history is laughable hyperbole. The first artificial satellite or first human in space, although less technically challenging, has greater symbolism when it comes to humanity’s outreach to space. Others will disagree.

Apollo manifested the intent to continue a lineage. All biological species go “extinct”, although through genetic drift, lineages may continue.Homo erectus per se is extinct, but through genetic drift the lineage continues in us. With the astrophysical forecasts of the remote fate of our planet and our sun, termination of all biological lineages would be expected. The giant leap for mankind is the potential to overcome the greatest of constraints thus far. Maybe it is one of the Great Filters still ahead of us in Fermi’s Paradox.

Back in the heady days of the 1960s, it did seem as if a scientific or commercial base on the Moon and beyond was almost inevitable. It now seems likely that 50 years after the last man left the Moon there will still be no return. If the 1960s’ launchers are the biplanes of the 20th century, it seems as technology has largely stalled, and we are just making more, possibly cheaper ones, but that the jet age equivalent never arrived, and with it the stillbirth of commercial space travel. My grandparents lived to see the birth of flight and flew in a Boeing 747 before they died. Until very recently, human spaceflight seems stalled in an era much like those early pioneers of flight like Amy Johnson, but with a lot more help and backup.

In the meantime, our technological capabilities in computing and miniaturization continue apace, which has led to the astoundingly successful planetary probe program. While Clarke envisaged a heroic attempt to reach Saturn with a crewed ship, he never suggested that we might reach Pluto, yet New Horizons did just that, returning more science and knowledge than the crewed Discovery could. Without this progress, I would be very disillusioned about exploring space.

On a recent Facebook post where someone posted a question about “why was it so hard to return to the Moon”, some wag commented that the people with expertise who made it happen back in the 1960s are now in nursing homes. (A modern version of J G Ballard’s post-Apollo visions of decline and decay?) Meanwhile, after Edmund Hilary’s successful ascent of Everest in 1953, there are lines of climbers trying to ascend Everest every year. After Piccard’s descended in a bathyscape to the Mariana Trench in 1960, there is a thriving tourist and commercial business in manned deep submersibles, some capable of reaching that depth. There are Antarctic bases doing all sorts of useful work. But on the Moon, there is nothing but [mostly dead] machines and the remnants of Apollo experiments.

At the end of the movie Apollo 13, Tom Hanks as Jim Lovell plaintively asks “I look up at the Moon and wonder, when will we be going back, and who will that be?”. I wonder that too.

“On a recent Facebook post where someone posted a question about “why was it so hard to return to the Moon”, some wag commented that the people with expertise who made it happen back in the 1960s are now in nursing homes. ”

You know Alex , I have seen this comment elsewhere, some guy on You

Tube had a whole video about it. I worked until 2010 before retiring and until 2013 as a consultant and young men and women (lots more women now) some now getting into their 40s now, are probably more competent than we were then! Most these days have Aerospace Engineering degrees which almost did not exist back in the 1960s. Just look at what JPL does these days with ‘younger’ engineers, and Space X has an outstanding lot. Around the world there is more talent for space flight than ever but there sure is a shortage of political will. Space X and Blue Origin , some others, may be the place to work these days.

I once read something about how current test pilots could never do some of the things that were once done. (It may have been Milt Thompson, IDK). Today there is a lot more safety involved in test flying. In the UK, after WII, there is that famous crash of a Vampire flying low over crowds. Maybe suffering bombing raids made people less concerned about risks then. You may know whether the same applies to Nasa. Have procedures been made much more safety-conscious than back in the 1960s? My only sense of it was a point made by a recent ISS astronaut (Chris Hadfield?) that every time anything does not go according to plan, the procedure protocol is updated and extended. This seems the very opposite of “flying by the seat of one’s pants”. Being involved in simulator training, what do you think has changed and how might it slow down (if at all) renewed Moon flights?

From Mercury through Apollo there sure was a sense of ‘probabilities’ … tho I have to say there were more ‘eyes’ in those days. As less structured as operations were there sure where a lot of ‘fine tooth combs’ going over everything. But it sure was not like Chuck Yeager’s X-1 flight. If one listens to the audio on those Apollo 11 landing videos … man… the amount of attention to detail that went into training and operations was industrial strength. The best example was the preparation of the Saturn V’s, Marshall checked over those, especially Apollo 8, centimeter by centimeter.

That said there sure was a change with the loss of the Challenger… and a nitrogen tetroxide accident at JSC in 1994…

NASA safety culture is still a bit over kill…… which can also be a dangerous thing … false confidence by thinking one can get 99% by class room lessons.

I note that we did more seat-of-the-pants simulator training with the Apollo Simulators , during Shuttle things were very structured , one reason I left Shuttle sim training , early, to design flight planning software for about 12 years.

Right now things go so slow due to limited resources I don’t have a feel for new large scale operations like a Moon Base would go.

During the 50th anniversary excitement of the Apollo lunar landing, it is easy to forget just how much of a failure it was in terms of creating momentum for further manned space exploration. Politicians created and supported it as part of Cold War competition and when that particular competition ended, the politicians had no further interest in grand scale space exploration nor did the American public. Did the end of serious space exploration cost them a single lost seat in the House of Representatives, Senate or Presidency? I sincerely doubt it.

Of course, there will be no end to self-congratulations over what was truly a magnificent engineering project, but it meant very little in the grand scheme of things. Others may disagree.

Oh, and saying Neil Armstrong will be the only name remembered 50,000 years from now is ridiculous but it plays well in the press which is all Ballard likely wanted.

I doubt that. Ballard was never a man who played the press for advantage. He didn’t need to, and wasn’t remotely interested in trying.

My mistake. I was thinking of Robert Ballard. But, the claim that Neil Armstrong will be the only name remembers from this era 50,000 years from now is, at best, just wishful thinking.

The Apollo project may be remembered for a few more centuries as the greatest engineering project of its era but that is about it. Whoever masters fusion energy, for example, would have a vastly greater impact on humanity’s future development and would be remembered accordingly. If the tomakak becomes the future or tri-alpha or whatever should lead humanity to the next level of development, that will be remembered in some dim way 50,000 years from now.

Which name[s] do you remember from 10,000 years ago? 5,000? In Britain, William the Conqueror and King Harold are the 2 names people can readily remember just 1000 years ago in England. About 500 years ago how many names can you recall? Which people are commemorated with statues?

Whether Armstrong’s name is remembered or not, the first Moon landing will be remembered, just as the Wright’s first heavier than air powered flight is. I suspect that just as Wilbur and Orville Wright are remembered, so will Armstrong, as both events are so seminal.

The moon landing is regarded as the seminal event in the western world mostly because it was done in the western world. Gagarin is likely more well remembered in Russia for example as the true space pioneer. So, the person most likely to be remembered will be a direct function of the dominant civilization. It is cliche but applicable here – the winners right the history.

Chinese undoubtedly remember an entirely different set of historical characters. To them, the name of William the Conqueror is a nobody. If Chinese/Asian cultures dominate the world for the next few centuries, the world will remember a different history. From my limited experience, civilizations rarely memorialize/celebrate those from another civilization.

Of course we tend to recall people of our own culture. That is why I prefaced with “In England…”. Having said that, the West does not write out other culture’s histories. Egyptian pharaohs building pyramids, emperors unifying China, etc. are remembered. Gagarin may be remembered as the first man to go into orbit, but it may not be considered such a seminal event as the Moon landing. We remember Columbus, but few of his forebears who started to navigate the oceans. The Vikings, and possibly even the Chinese, had reached the American continent first (after the human migration), which may reinforce the cultural aspect of who is celebrated. (We certainly do not know who was the first to migrate onto the American continent during an ice age 10s of thousands of years ago.) One advantage Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins have is that there is a small “monument” on the Moon. Unless it is vandalized or looted in the coming millennia, it should last for a very long time to celebrate the achievement.

I respect your comments and analysis however the West does indeed write out history that is uncomfortable to the dominant society and eventually that history in every form may be lost. I have personal testimony to that reality regarding certain genocidal activities written out of Western history as the perpetrators are still very much in power and good standing. I suppose that in a century or two, that particular genocide will have been fully erased from all forms of history. No, I will not go into details. Based on general principals, I suspect that there are other such historical events that will forever be lost as the human ability for denial seems near-infinite.

Back to Armstrong, I regard the Apollo moon landing as a magnificent engineering achievement and should be recognized as such. However, it was driven by one-off Cold War ambitions and led to no further explorations. One would expect more from a seminal event.

We can agree to disagree:)

I don’t know what you are referring to, but I hope you are not equating “The West” with the USA. In my own experience, Britain which was the global hegemon, had white washed its imperial history, but nevertheless, historians are digging up that history and revealing all the warts. The upcoming power, China, is clearly unable to bury its history including the massacre at Tiananmen Square, despite very strong efforts by the state. The attempts by some US states to rewrite US history textbooks for schools is equally doomed. The liberal enlightenment pretty much ensures that someone will research the past and expose uncomfortable facts and events. As we see with China, authoritarian states can try to censor history, but it will not be successful. IMO, the increasing amount of data and ease of copying digital information will make censoring history almost impossible. States, organizations, and individuals may temporarily control the narrative, but it seems inevitable that denying the truth will fail over the longer term.

Would the landing on the moon be equally venerated if Soviet cosmonauts stepped out of the lander? I think not. The main focus in the US would likely have been on who betrayed the US space effort and similar finger pointing. No claims of a 50,000 years memory would be made, that I am sure.

Alas, we are poles apart in interpretation of history and power.

A bright spot, however, is the internet which was wrested partial control of history from the institutions. Lets hope that the people who lived the history can now write it.

To be clear, I enjoy your posts and usually agree with your comments.

Here are two good videos about the Apollo 11 landing:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xc1SzgGhMKc

When I was working in the Apollo program I had access to the flight directors loop.

On TV they did not broadcast the flight directors loop which I was listening to that day in July.

https://www.firstmenonthemoon.com/

-Air-to-Ground Loop (Left Audio Channel)

-Flight Director’s Loop (Right Audio Channel)

Also note the bottom left-hand rectangular blocks. They light up to identify which Houston Mission Operations Control Room 2 (MOCR2) console location is talking on the loop. Schedule 25-30 minutes to listen to the entire landing sequence.

Note:

When Aldrin says at 102:45:43 GET – “ Okay. ENGINE STOP and ACA out of Detent”

they are sitting on the Moon.

So the first words from the Moon are Aldrin’s.

I asked Buzz about this once and he said “Nobody cares about details like that.”

Fantastic

Apparently Buzz never saw the Apollo Lunar Surface Journal:

https://www.hq.nasa.gov/alsj/a11/a11.html

Hi Al,

I remember going to the Esso station in Alamogordo, New Mexico (I was born on Holloman AFB) with my dad and getting these cardboard cut-out models of the LM and CM that you could put together. All you had to do was buy a tank of gas. Thanks for jogging that memory out of the cobwebs of my skull full of mush.

My younger son was an infant when the First Landing occurred. I was glued to the TV . . . Don’t really remember the last one. I guess it had no more entertainment value. So, we’ve been there, done that. I am unsure of any reason to do it again. Like, how many people have climbed Mt. Everest twice?

Quite a few in fact. They are the guides, mostly Sherpa, who make their living doing so.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Mount_Everest_summiters_by_number_of_times_to_the_summit

The economic analogy is apt with respect to the moon. If we ever develop economic interests on the moon there will be numerous individuals with multiple trips under their belt.

The cost of a mission exceeds the value of anything that could be obtained. Economics cannot justify the trip. Mining? Heavy equipment lifting would bankrupt any nation. Sherpa guides are the equivalent to the profit-supported earthbound infrastructure who feed at the public trough.

Historically, anything that was brought from a long distance was very costly. Typically they had to be unique items, silk, spices, etc. The Moon may or may not have rare minerals that are worth returning to Earth.

In the early days, facilities for super-wealthy tourists might best be serviced with long stay staff, manning hotels and lunar entertainment facilities. Once there, entrepreneurs will no doubt start side businesses to serve the tourists. Those tourist destinations then become colonies in their own right. Once a colony is established and growing, there may eventually be a period when only a little trade is needed for items that cannot be grown or created locally.

Settlers/colonists rarely have anything worth trading, especially while subsistence farming or in early industrialization. However, eventually trade is worth doing. Ricardian comparative trade advantage might work depending on transport costs for the items involved. Probably very high value per unit mass would be needed.

Economic issues have come to dominate the industrial and post-industrial era. That is probably a box that blinds us to the many other reasons to go back to the Moon, and to stay. We shouldn’t dismiss them simply because no commercial logic works.

The moon is far from fully explored, especially directly by humans (maybe a week and a square km or 2).

Suppose you were close enough to Everest to regard it as a (supposedly) fully-known neighbour, but travelling far away to climb a new mountain.

If you and your crew hadn’t climbed more than the back porch for 45 years, wouldn’t it be sensible to practise on “Everest” (and maybe K2) first?

Why did the LM door have a lock at all? Were they afraid someone would try to steal it while the crew were out on EVA?

I had wondered about that lock myself. Maybe Al can tell us what it was all about.

That reminds me of a favourite cartoon by the wonderful Don Martin (even if it apllies to later missions really):

I’m afraid the image didn’t come through, Michael. Can you forward a link? Thanks.

Sorry Paul, it may not have worked due to being a Pinterest image. Try this:

https://www.madmagazine.com/blog/2014/07/18/don-martin-one-thursday-afternoon-on-the-moon

Comes through fine. Thanks!

Presumably they wouldn’t want it flapping about and needed a way of securing it while LM was unmanned and couldn’t be locked from inside (i.e, during launch and before crew transfer)? But it seems weird if its mechanism could potentially lock people out. They should’ve asked Kubrick about that! :-)

There was one Apollo LM crew recorded while talking who were actually whispering, then asked themselves why they were whispering on the Moon!

Several questions and comments here. To say that I was disturbed by the fact that Neil Armstrong left the simulator one day to strike up a cigarette, even if it was his only one for the year, seem very disturbing to me. I realized that people smoked more than then now, but I thought that Armstrong was so disciplined that he recognized the dangers of smoking and wouldn’t smoke at all.

Could Al Jackson explained to us a bit more of the details in regards to the simulators that the astronauts used? How (for example) very realistic was the simulation of the spacecraft that was projected? How about the realism of the planets? The placement and visualization of the stars?

Online you see a tremendous number of so-called simulations of spaceflight, which presumably uses Apollo type spacecraft, but they all seem very, very crude in their presentation. Does Dr. Jackson have any comment about these online Internet simulations and how they contrast to the simulation he worked with?

Would Dr. Jackson be able to tell us if the software that was used in the simulations is available for playing around with, either through purchase or made available in a gratis type of situation? It seems like it might be fun if one had a very powerful computer to be able to attempt one’s hand at what the astronauts went through and see how a person stacks up.

With regards to the LM module door, what would have the two astronauts have done if the door had been inadvertently locked as the last astronaut descended the ladder? Would they have been out of luck or could they have in some fashion gotten back in; I’ve always wondered the answer to that question.

Finally, as a both question and comment there is a presentation today about how NASA is accelerating its efforts to get to the moon again and Mars in the 2030s. From my standpoint they seem to be in quite a rush and I don’t really understand why they think they must hurry, hurry, hurry. It seems like those individuals who will be making the voyage to Mars have a lot of technological hurdles which won’t be solved by going real, real fast. You can see what I’m talking about in the link below:

https://finance.yahoo.com/news/nasa-funds-private-space-race-as-astronauts-aboard-iss-prepare-for-mars-201814316.html

Finally, I just want to add how personally sad I am that Neil Armstrong is not here with us to see the fiftieth anniversary, it seems that we are supremely missing something without him being present.

Charlie,

I can you Neil was an angel about smoking. Astronaut Ed Mitchell was a chain smoker , we hated going to his office, the few times we did. I don’t remember Mitchell smoking in the simulator. I am not sure but I don’t think Buzz was a smoker. In those days a lot of people smoked it was a just an ordinary facet of life then. Anyone of certain age these days knows what I mean.

O the equipment for the late 60s was very good at the visuals. There was a deal we called the Star Ball which when seen out the windows and through the navigation ‘telescope’ was very accurate depiction of the astronomical sky.

The LMS was a VERY expensive piece of equipment , one can see how much there was in the first photo above. It was very good at displays out the cockpit window even tho all was analog at the point of delivery.

As for the software , Google it , some people have recreated the on board computers and some of it is on line I think. If you mean the whole global set of software from that time like what ran the visuals and equations of motion, I have no idea. There may be printouts.

Paul, I am not sure what a lock on the egress hatch means , the LMS did not have such a thing just a back door to get into the cockpit. Someone will have to look up that from a LM manual, which I am sure is on line somewhere.

I still see and know the younger engineers at JSC (some not that young now!) and from what they tell me unless there is a bigger commencement of resources there is not going to be a Lunar Base , or Mars expedition or transportation node in the next 10 years. My sense of things is that Space X cannot do that either. If there were a serious international effort , a pooling of resources, I could see it, but there is no political will for that either.

My overriding feeling at this point in time is appreciation for what I witnessed as a teen watching men walk on the moon and deep sadness that we have not progressed whatsoever in manned exploration in 45 years or so since. I never would have believed it back then. Mars is such an obvious target and will remain so until we go there. Humans have a huge role to play in determining whether life still exists on Mars, probably in microbial form underground but there is so much else we can discover by going there including how to live away from the Earth and how independent of Earth we can become.

The Apollo Lunar Module Documentation is at:

https://www.hq.nasa.gov/alsj/alsj-LMdocs.html

for those interested.

Travels with the Apollo 11 crew.

I mentioned above that the GN&C instructors , sometimes, traveled with the crews to briefings at MIT (really MIT Instrumentation Laboratory ) in Boston in those days, and TRW at Redondo Beach.

I remember that at MIT we were served lunch from a cart of store bought packaged sandwiches and tepid milk , the crew had to eat the same. New England frugality?

Those MIT guys were the most impressive technical people I ever met in the program. I remember the Grand Master of Astrodynamics Richard Battin was in the audience, but he did not lecture. ( https://www.nap.edu/read/23394/chapter/7#33 ).

I can remember that night we and the crew and some MIT guys went to Durgin-Park but we sat in a different part of the room (from the crew) and MIT did not pick up our tab.

During the visit we also saw MIT’s version of the primary guidance and navigation computer. They had a pretty good cockpit mock up… but the rest of the room was a bird’s nest of wires and electronics…wish I had taken a picture… tools laying about…it looked like a mess… that’s when I realized those guys knew what they were doing because that thing worked!

Out at TRW we had this huge fancy dan conference room. That is where Neil gave that rendezvous chalk talk that I described. Buzz sat there quite pleased, I am thinking Buzz had given that talk so many times that he was tired of it! The reason we were there was because TRW had the Abort Guidance System which was the backup system of the primary , it could only do abort ascents and rendezvous.

I remember TRW took us to their cafeteria , can’t remember what I had, but the food was excellent. That evening TRW took us the a large Ramada Inn in or near Redondo Beach. I do remember excellent prime rib and the only time I have ever had Baked Alaskan. There was so much alcohol you could have gotten a whale hammered! We did not sit with the crews that was for TRW brass. TRW did pick up the tab on that one.

Those trips to LA were not as interesting as the ones years before when I worked on the Lunar Landing Training Vehicle. One of our guys had a Playboy Key! So on the way back from Edwards Air-force Base we would have lunch at the LA Playboy club… which had the damnest gourmet buffet I have ever seen! … and no there were no bunnies about for lunch! Tho there were attractive women in that dining room. (LA was a horrible place to go in the late 1960s, moment you stepped out of the plane your eyes stung from the awful LA air.)

Thanks indeed for sharing your memories Mr Jackson.

Excellent article on the 1970 film Marooned, which goes into detail about why the Apollo spacecraft named Ironman One had to have such an extreme technical failure to become stuck in Earth orbit because the engineers of the real vessel made such a scenario almost impossible to happen!

http://www.thespacereview.com/article/3723/1