One of the many legacies of the Voyager spacecraft is the Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe (IMAP). Scheduled for a 2024 launch, IMAP has as part of its charter the investigation of the solar wind’s interactions with the heliosphere, drawing on data from an area into which only the Voyagers have thus far ventured. Let me hasten to add that IMAP will stay much closer to home, orbiting the Sun-Earth L1 Lagrange point, but like the Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX), it will help us learn more about a region physically reachable only by long-duration craft.

The fact that we’re still talking about Voyager as an ongoing mission is the story here. Launched in 1977, the doughty probes have kept surprising us ever since. In terms of their longevity, I noted in 2017 that when Voyager 1’s thrusters had begun to lose their potency (they’re needed to keep the spacecraft’s antenna pointed at Earth to return data), controllers were able to fire a set of backup thrusters that hadn’t been used for a whopping 37 years.

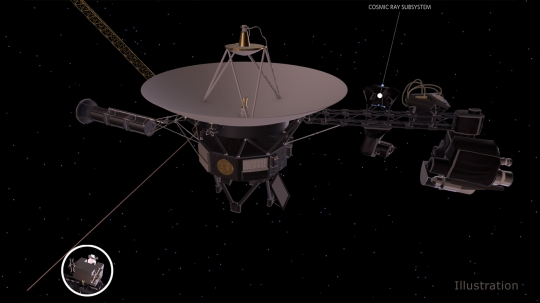

Even the Voyager Interstellar Mission, an extension to the primary, is long in the tooth, having begun when the two spacecraft had been in flight no more than twelve years. These days Voyager is all about power management, for we’re still getting good data. Voyager 1’s cosmic ray instrument is still at work, along with a plasma instrument, its magnetometer, and its low-energy charged particle instrument. Voyager 2 likewise studies cosmic rays, operates two plasma instruments, a magnetometer, and its own low-energy charged particle instrument.

Voyager instruments are proving to be as tenacious as bulldogs. Consider: Voyager 2’s cosmic ray subsystem (CRS) continues to run although engineers have turned off the heater that keeps it warm to save power, as part of a new power management plan for both spacecraft. The CRS now functions at -59 degrees Celsius, a good 15 degrees colder than it was originally tested for back in the days before launch. Voyager 1’s ultraviolet spectrometer continued to function for years after losing its heater as part of an earlier power strategy implemented in 2012.

Voyager project manager Suzanne Dodd (Jet Propulsion Laboratory) notes how important it is to make choices about power and instruments, given that the heat available from the three radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) aboard each craft decreases with time, for each spacecraft produces 4 fewer watts of electrical power each year. We’re down to 60 percent of the heat energy the RTGs could produce at launch, so hard decisions have to be made about which systems to keep operational. Says Dodd:

“It’s incredible that Voyagers’ instruments have proved so hardy. We’re proud they’ve withstood the test of time. The long lifetimes of the spacecraft mean we’re dealing with scenarios we never thought we’d encounter. We will continue to explore every option we have in order to keep the Voyagers doing the best science possible.”

Image: This artist’s concept depicts one of NASA’s Voyager spacecraft, including the location of the cosmic ray subsystem (CRS) instrument. Both Voyagers launched with operating CRS instruments. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

The cosmic ray subsystem had its heater turned off despite its role in detecting Voyager 2’s passage through and exit from the heliosphere, the ‘bubble’ produced by the outflow of solar wind particles from the Sun. One aspect of this difficult choice is that the CRS can only look in specific fixed directions, making its heater in this environment expendable. Voyager 2 is driving the new power plan because it has one more instrument collecting data than Voyager 1.

If there is one place where power remains essential to the last, it’s the fuel lines that power the Voyager thrusters. In addition, Voyager 2’s current thrusters are degrading, just as Voyager 1’s did, forcing a switch to trajectory correction maneuver (TCM) thrusters last used during the encounter with Neptune in 1989. That switch should take place later this month. Let’s give a nod to Aerojet Rocketdyne, whose MR-103 thrusters have performed beyond all expectation, as has the mission itself, originally slated to last but five years.

One day, probably in the coming decade though perhaps late in it, the amount of electrical power needed to keep both spacecraft operational will no longer be available. Here’s hoping we get at least eight more years out of the Voyagers so that they’re still with us on their 50th anniversary. My own hunch is that the gifted people managing the Voyager Interstellar Mission may just find enough tricks to get them through to 2030 before the flow of data ceases.

As I’m still delighted to say, this mission isn’t over. Go Voyager.

I don’t have much to add, except to second your “Go Voyager”. What an incredible trip, and what robust systems…

This is important for breakthrough starshot because it shows not only can we but we have built a ship that can last and last.

Go Voyagers, indeed!

Let’s look into similar reliability of manufacturers for future long-term and/or open-ended programs. And that of long-duration (open-ended?) power supply.

I would like to know whether the longevity is due to some engineering approaches, or if we can expect all our current instruments to survive as long.

One thing I do recall is that older chips with their much larger feature widths are much more resistant to radiation than modern chips. However, we can now harden chips against radiation and self-healing chips are another approach to resist the damage due to radiation.

As stated in the excellent 2017 documentary The Farthest: Voyager in Space, the design of the two Voyager probes were frozen five years before their launches, in 1972. So this makes their endurance even more remarkable.

https://centauri-dreams.org/2018/10/12/the-farthest-voyager-in-space/

To quote:

As a nice counterpoint, this demonstration was immediately followed by a clip with Voyager Project Manager John Casani, who asked: “What’s wrong with ‘70s technology? I mean, you look at me, I’m [19]30s technology!” Casani added that he makes no apologies for the “limitations that we were working with at the time. We milked the technology for what we could get from it.”

Seeing how the Voyagers have lasted well beyond their initial planned encounters with Jupiter and Saturn from 1979 to 1981, with every intention of recording and returning scientific data on the interstellar medium for perhaps two decades more, no apologies are necessary, indeed.

This is likely a stupid question, but would it be conceivable to heat the Voyager probes by shining lasers or other EM radiation at them? It would be at least very difficult and/or expensive to do such remarkable targeting, and I assume much of the data collected by the craft might be compromised by unpredictable alterations of temperature and trajectory from the light pressure. Still, as they approach end of life, the chance to test a favorite sci-fi trope seems enticing, and the potential for accelerating or targeting their interstellar trajectory would be good for morale.