The Kepler mission gave us, along with plenty of exoplanetary scenarios, a statistical look at a particular patch of sky, one containing parts of Lyra, Cygnus and Draco. Some of the stars within that field were close (Gliese 1245 is just 15 light years out), but the intention was never to home in on nearby systems. Most of the Kepler stars ranged from 600 to 3,000 light years away. Instead, Kepler would produce an overview of planets around different stellar types, including some in the habitable zone of their stars.

As with all such observations, we’re limited by the methods chosen, which in Kepler’s case involved transits of the host star. TESS, the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, likewise uses the transit method, though with particular reference to broad sky coverage and close, bright stars. We can deploy the widely anticipated James Webb Space Telescope, to be launched next year, to follow up interesting finds, but let’s also consider how useful the Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST) is going to be, for this instrument brings a new population of planets into the mix.

Not that WFIRST won’t be able to spot transits as well, but the real interest here is microlensing, a phenomenon a good deal less common than transits, but one holding the promise of finding planets far more distant than Kepler. Looking toward the passage of a star and planetary system in front of a background star, astronomers can catch the lensing effect produced by the warping of spacetime. That quick brightening can contain within it the signature of one or more planets.

As you would imagine, finding these occultations is tricky, for they don’t occur very often. David Bennett is head of the gravitational microlensing group at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. Kepler monitored more than 150,000 stars in its primary mission, but WFIRST will have a lot more to play with, says Bennett :

“Microlensing signals from small planets are rare and brief, but they’re stronger than the signals from other methods. Since it’s a one-in-a-million event, the key to WFIRST finding low-mass planets is to search hundreds of millions of stars.”

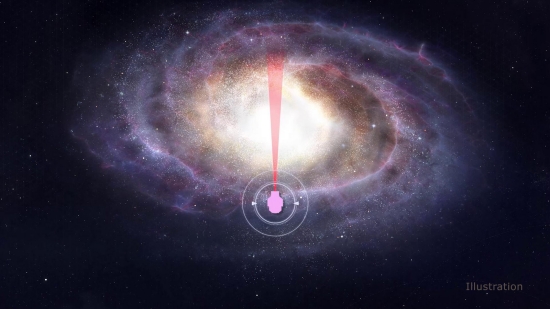

Image: WFIRST will make its microlensing observations in the direction of the center of the Milky Way galaxy. The higher density of stars will yield more exoplanet detections. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/CI Lab.

Slated for launch in the mid-2020s, WFIRST will round out what we’ve learned from previous missions and different exoplanet detection methods. Radial velocity is sensitive to planets close to the host star and, with ever greater spectroscopic precision, can tease out information about smaller worlds further out. Transits are excellent for finding small worlds in tight orbits. What microlensing brings to the table are planets of all sizes — and perhaps even large moons — orbiting at a wide range of distances from the host, as far out as Uranus and Neptune and potentially much farther.

Here the bias, if we want to call it that, is toward planets from the habitable zone outward, fully complementing our other methods, which function so much better in inner systems. We have no idea how common ice giants are, but WFIRST should help us build the census. We go from Kepler’s 115 square degree field of view of stars typically within 1,000 light years to a 3 square degree field that, because it’s toward galactic center, will track 200 million stars. Their average distance will be in the range of 10,000 light years, far beyond the reach of other methods.

Microlensing has produced its share of planets — 86 so far — but bear in mind that the observations that have turned them up have been in visible light, which means that looking toward the center of the galaxy, shrouded in dust, has not been feasible. That’s beginning to change with the United Kingdom Infrared Telescope (UKIRT), which from its vantage in Hawaii has begun mapping the region. Data from UKIRT will help determine the WFIRST microlensing observation strategy.

Savannah Jacklin (Vanderbilt University) has led studies using UKIRT data:

“Our current survey with UKIRT is laying the groundwork so that WFIRST can implement the first space-based dedicated microlensing survey. Previous exoplanet missions expanded our knowledge of planetary systems, and WFIRST will move us a giant step closer to truly understanding how planets – particularly those within the habitable zones of their host stars – form and evolve.”

But WFIRST microlensing goes beyond exoplanet discovery to take in everything from black holes to neutron stars, brown dwarfs and ‘rogue’ planets that have been ejected from their planetary systems. TESS is currently tracking 200,000 stars over the entire sky. The infrared studies of WFIRST will dramatically add to what Kepler and TESS have given us, using machine learning tools now being refined by UKIRT to comb through the data. An overview of planetary populations at all distances from the host star, and with a target field containing hundreds of millions of stars, is the much desired result.

Amid the excitement and ongoing battle over the ground breaking WFIRST exoplanet direct imaging coronagraph it’s gravitational microlensing survey of the Galactic bulge is oft forgotten. Yet vital . Unlike most exoplanet detection methods it can finally target large numbers of down to Earth mass planets orbiting in hab zones and out to several AUs. Beyond the ‘snow line’ of Sun like stars . Jupiter distance certainly. Extending exoplanet “discovery space “. So in conjunction with Kepler , TESS and Gaia’s Jupiter mass and distance astrometry – should finally give a more representative view of the exoplanet population . Not just hot Jupiters, Super Earths and mini Neptunes – around M dwarfs . Conservative estimates for about 2200 planets – optimistically twice that . With many more “free floating” planets .

United Kingdom Infrared Telescope (UKIRT)

Don’t forget to include that one on your list.

Done.

Thanks for this article. Micro-lensing is the detection method I have been the one that has been the most obscure to me. In some ways, I guess it actually is. But this certainly helped. Now given what was said thus far, I have to wonder how much information is obtained in a first event: a transit time and a suggestion of how fast based on a proximate star?

Should the event be for a rapidly orbiting planet, then I would guess there could be a chance of a repeated event – and consequently an orbital period that would shed some light ( or extinguish it?) on how wide an object the micro-lensing agent is. If this is an infra red band

observance, then is there any chance of getting some characteristic infra red information about the planet itself?

The concept of a galactic habitable zone analyzes various factors, such as metallicity (the presence of elements heavier than hydrogen and helium) and the rate of major catastrophes such as supernovae, and uses these to calculate which regions of a galaxy are more likely to form terrestrial planets, initially develop simple life, and provide a suitable environment for this life to evolve and advance.

Peter Jonnes,

Regarding galactic habitable zones and obtaining information, would not the stars themselves offer information on these issues? Is it that the microlensing events indicate a statistical indication of how many planets are located in stellar vicinities and thereby connecting stellar information with planetary detections? If I had my druthers, should I not prefer getting a transit because it would reveal more than a micro lensing?

Yes and no.

Microlensing events are short term one off events. Transit photometry however is heavily biased towards larger planets orbiting closer in to smaller stars. Like RV spectroscopy – though over its four year primary mission Kepler helped push this boundary out nearer to an AU – from the fractions of this distance described by the RV method . ( for somewhat smaller planets too, reaching down from Neptunes to sub Neptunes and the increasingly defunct ” Super Earths”)

Microlensing pushes this discovery space further out again – for all stellar classes, locating planets as small as Earth or smaller out to several AU. So the information on individual planets might be less, but taken together as a whole, microlensing surveys offers a more representative view of planetary populations. A conservative estimate for WFIRST is nearly four thousand. The same again on top of what is currently known. Crucially extending out beyond stellar “snow lines” – which appear to be an important demarcation line for planetary formation – pebble accretion versus circumstellar disk instability. A view which dovetails nicely with preexisting observation techniques and which will ( along with Gaia and it’s astrometry method – which favours a similar expanded discovery space out to about 5 AU – though currently only with sensitivity for gas giants and proximate Neptune mass planets) offer a far more accurate view of exoplanet distribution closer to the physical reality.

When the first exoplanets where discovered around sun like stars by Doppler spectroscopy they were all “hot Jupiters” . Since then thanks in no small way to Kepler, such planets have been found to be rare. At present Neptune and sub Neptune planets seem to be the most common . However, once the combined results of two decades or so’s worth of different Exoplanetary surveys are available – covering the full range of masses and orbital distances – I reckon that rocky, terrestrial mass planets will ultimately turn out to be the commonest.

Like Andy below i fear for WFIRST post COVID. Even if it does fly I think the likelihood of it having a coronagraph now will have diminished substantially , in which case it’s microlensing survey will become all the more salient.

I have to wonder if WFIRST is going to fly: it’s been on the chopping block several times now. Given the likely impact of COVID-19, I wouldn’t be surprised if it ends up getting terminated.

“TESS is currently tracking 200,000 stars over the entire sky, with typical distances of 100 light years.” Are you saying there are 200,000 stars within 100 light years of us?

No, and now that you mention it, I don’t like that sentence either. I’m going to go back and re-phrase in the original. Thanks for pointing this out.