What intrigues me about Kepler-1649c, a newly discovered planet thrust suddenly into the news, isn’t the fact that it’s potentially in its star’s habitable zone, nor that it is close to being Earth-sized (1.06 times Earth’s radius). Instead, I’m interested in the way it was found. For this is a world turned up in exhaustive analysis of data from the original Kepler mission. Bear in mind that data from the original Kepler field ceased being gathered a full seven years ago.

I share Jeff Coughlin’s enthusiasm on the matter. Coughlin is an astronomer affiliated with the SETI Institute who is a co-author on the new paper, which appears in Astrophysical Journal Letters. One of the goals of the mission that began as Kepler and continued (on different star fields) as K2 was to find the fraction of stars in the galaxy that have planets in the habitable zone, using transit methods for initial detection and radial velocity follow-up on Earth. Of the new find, made with an international team of scientists, Coughlin says:

“It’s incredible to me that we just found [Kepler-1649c] now, seven years after data collection stopped on the original Kepler field. I can’t wait to see what else might be found in the rich dataset from Kepler over the next seven years, or even seventy.”

Yes, because we’re hardly through with a dataset that has taken in close to 200,000 stars. What the new planet reminds us is that the initial detection stage of Kepler’s work long ago ceded to analysis of how many of the acquired signals are due to systematic effects in the instrumentation, or variable stars, or perhaps binaries, for so many things can appear to be the signature of a planet when they are not. Making computer algorithms to automate this work has occurred only after intensive human study to learn the best ways to distinguish between signals.

But consider: The algorithm, called Robovetter, that was used to distinguish false positives was working on data in which only 12 percent of the transit signals turned out to be planets. We have false positives galore, out of which we now get the Kepler False Positive Working Group to serve as a double-check on the algorithm’s work. The KFPWG is a dedicated team indeed, taking years to review the thousands of signals from the original Kepler dataset. Kepler-1649c comes out of this review, a world that had been misclassified by the automated methods earlier on. Clearly, humans and machines learn from each other as they make such difficult calls.

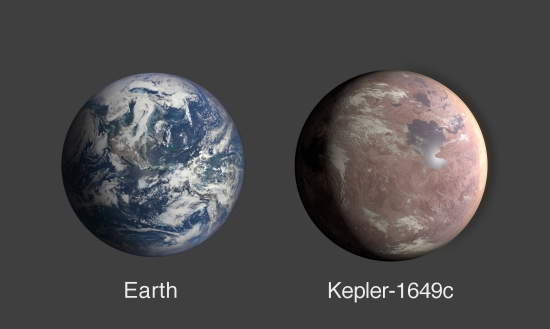

Image: A comparison of Earth and Kepler-1649c, an exoplanet only 1.06 times Earth’s radius. Credit: NASA/Ames Research Center/Daniel Rutter.

I yield to the experts when it comes to habitability, and trust our friend Andrew LePage will weigh in soon with his own analysis. What we do know is that this planet receives about 75 percent of the amount of light Earth receives from the Sun, though in this case the star in question is a red dwarf of spectral type M5V, the same as Proxima Centauri, fully 300 light years out. As always with red dwarfs, we bear in mind that stellar flares are not uncommon. The planet orbits its star every 19.5 days. We have no information about its atmosphere.

Even so, lead author Andrew Vanderburg (University of Texas at Austin) notes the potential for habitability:

“The more data we get, the more signs we see pointing to the notion that potentially habitable and Earth-sized exoplanets are common around these kinds of stars. With red dwarf stars almost everywhere around our galaxy, and these small, potentially habitable and rocky planets around them too, the chance one of them isn’t too different than our Earth looks a bit brighter.”

There is a planet on an orbit interior to Kepler-1649c, a super-Earth standing in relation to the former much as Venus does to the Earth. The two demonstrate an uncommon nine-to-four orbital resonance, one that hints at the possibility of a third planet between them. This would give us a pair of three-to-two resonances, a much more common scenario, though no trace of the putative world shows up in the data. If there, it is likely not a transiting planet.

I rather like the image that comes out of NASA Ames, where the Kepler effort is managed, but I like it as a kind of science fictional art, the sort of thing to be found on SF paperbacks. It’s evocative and suggestive, but of course we have no idea what this world really looks like.

Image: An illustration of what Kepler-1649c could look like from its surface. Credit: NASA/Ames Research Center/Daniel Rutter.

The paper is Vanderburg et al., “A Habitable-zone Earth-sized Planet Rescued from False Positive Status,” Astrophysical Journal Letters Vol. 893, No. 1 (1 April 2020). Abstract.

> I yield to the experts when it comes to habitability, and trust our friend Andrew LePage will weigh in soon with his own analysis.

I thought I felt my ears burning ;-) And yes, I’ll be working on a “Habitable Planet Reality Check” for this new find for publication in the next few days but Kepler 1649c looks *really* good at first blush.

Thanks Andrew I’ll be looking forward to reading that.

I worked on the analysis of the Kepler data as did many thousands of others. I was surprised by the apparent high frequency of occurrence of positives and am not surprised that many of them were shown to be false. The same goes for TESS, but the chance to work with the data is just a tremendous opportunity and honour. I look forward to more opportunities in the future.

Are there any interesting similarities between false positives that can be used to make an improved filter?

Amazing how needles missed in haystacks are later recovered. Could there be additional criteria / parameters that could be applied to the data sets which might lead to more recoveries?

What might be found if computers were trained to review and critique their own analyses, as IBM’s Watson did playing against itself with chess and go?

The problem here is that there is no feedback with “ground truth” to train the algorithms until telescopes can verify the hits. To some extent, it must be a judgment call. Some time back there was a CD post about changing the shape of the transit curve to better capture exoplanets that increased hits. I expect that this is teh sort of thing that is happening, the rejection of cases was reexamined with different criteria and this extracted new hits that were not rejected. Because of the need for expensive, slow, telescopic verification, feedback is very slow compared to the usual algorithmic training and no doubt astronomers are loathed to use the time to verify rejections are truly not false negatives.

Or a really well trained AI.

Indeed–look at how many outer planets’ moons were found in the Voyager data, years after the two spacecraft’s Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune encounters. (It’s the data-sifting equivalent of patiently going through tons of pitchblende to find pinches of radium.) Even most of the mid-1960s-vintage Lunar Orbiter 1 – 5 photographs of the Moon’s surface (which the informal “McMoon’s” group [based in an old McDonald’s hamburger joint at the NASA Ames Research Center; they also controlled and collected data from the ISEE-3 / ICE spacecraft for a few months] read off the old original tapes) are still awaiting analysis; being almost 55 years old, they allow comparison with recent images, to show changes. Also:

“Meshing” the data sets from different missions with the help of computers (to match–or nearly so–observation dates and times with the same given stars) could also confirm exoplanets, or refine their parameters, or weed out false positives, or even all three. Knowing the differing resolution capabilities of the various spacecrafts’ instruments, some positives wouldn’t “show” in the data from less-capable instruments. But that’s not a problem; it would be wonderful, as a list of such “gray box” targets could be compiled, and they could be checked again, using the most capable space-based and ground-based instruments.

I wonder if there will be any follow up of Kepler 1649C to confirm it with large ground based telescopes and the rest of that solar system planets?

100 parsecs away means it’s a far future destination for starships, unless we crack wormholes and warp drive. There will be many planets dangling beyond our abilities even as we creep out into the Galaxy.

Our reach, Adam (the stars and worlds we want to explore directly, by starprobe or starship) will always exceed our grasp (the worlds we *can* explore by those means). Improvements in telescopes–and their associated instruments–can get us some answers between starprobe and starship “technology generations” (having higher fractions of c velocities, or perhaps even effectively FTL [via Alcubierre’s warp drive] capability, as time and development work go on), and over time, our grasp will gradually increase. But only examining such planets from (at least) flybys, orbit, and (best of all) their surfaces can give us detailed information, such as the chirality (“handedness”) of any organic compounds–or life–there. A reasonably fast–say, 100-year flight time to target–probe (or a group of them), making astrometric and parallax observations of stars while en route to a nearer one (such as Proxima Centauri, Barnard’s Star, etc.) as a flyby target, would be a good first step in interstellar probe missions.

Hi Paul

“There is a planet on an orbit interior to Kepler-1649c, a super-Earth standing in relation to the former much as Venus does to the Earth.”

I was a little confused here was this second planet an inner one or an outer one?

Thanks Laintal

This planet orbits closer to the star than the newly discovered Kepler-1649c.

Thanks Paul

I have found the paper,

Day 23 of lockdown and I must be getting forgetful

Cheers

Going back to the Andrew Vanderburg quote:

I disagree with this because it runs up against the mediocrity. If this work is correct, “habitable zone” terrestrial planets are more common around low-mass red dwarfs, and low-mass red dwarfs are by far the most common type of star. These would then be the typical examples of habitable planets in the Galaxy. Despite this, we observe that we are on a planet around a rare, massive star that would have a lower probability of hosting a “habitable zone” terrestrial, which would be a rather atypical scenario.

Our situation becomes more typical if the habitability of planets around red dwarf stars is suppressed. My feeling is that the results on the frequency of “habitable zone” planets around low-mass stars strengthens the case that the vast majority of them are going to be dead worlds.

Gaaahh. “Mediocrity principle”.

But remember, the mediocrity principle–like Occam’s razor–is just a “rule of thumb,” not a law of nature. Both are often–even usually–right, but not always. The more complex of two supersymmetry theories in physics turned out, against Occam’s razor, to be the correct one, and:

Accidental close groupings of late F-type and/or K-type, and/or G-type stars (like Zeta 1 and 2 Reticuli, two Sun-like G-class stars; we can see other examples in the sky–we just happen to not be beneficiaries of such a fortuitous arrangement) go against the principle of mediocrity, yet they exist. Such close groupings give any inhabitants of such stars’ planets much easier interstellar travel and SETI targets, with at least even odds (50/50), if not better, that their close neighbor systems also harbor life of some kind (or at least have habitable planets).

Going against the mediocrity principle isn’t that big of a deal. A random sample can come from any available data set. It does predict that life is more likely to be found around Earth like planets but the selection process is vulnerable to things like selection bias or anthropomorphism. Anyone on a world orbiting any star type could make an argument based on the mediocrity principle.

That being said, from what we know of red dwarfs, they aren’t ideal stars for life. Planets in their habitable zone will be tidally locked and subjected to intense flair activity. What I think Andrew Vanderburg is saying is that the probability of there being living worlds around red dwarfs increases as the population of red dwarfs increases. I don’t think he is predicting that there are more living worlds around red dwarfs than sun like stars.

We pretty much know Earth is atypical in a lot of ways, which indicates to me that the mediocrity principle doesn’t really apply here. For instance, giant moon that we’re not tidally locked to, so we get tides.

Mediocre worlds with life are probably inhabited by algae and bacteria.

What’s going on here, I think, is mainly that our techniques for finding planets work best for low mass stars.

The Mediocracy Principle does not apply here . It cannot. The Kepler data set – in either of its two iterations – does not make a random cohort make . It , like all current exoplanet cohorts is subject to large systematic biases. Favouring larger planets, orbiting closer in to smaller stars.

So what applies to any analysis of such populations is Daniel Kahnman’s ‘Availability bias’. We go with what we see right in front of us. The most fundamental of all biases . The main reason why the history of astronomy and astrophysics is littered with apparently surprising and “unexpected“ findings – thanks to tenuous conclusions being drawn from limited data sets ( with the “atypical” Earth being the ultimate limited data set)

We are constantly reminded about the magnificent greater than 4000 population of exoplanets . As if that means we can draw all the conclusions we want . This figure is undoubtedly impressive – when compared to even just twenty years ago . It has even been indicative too. Up to a point. Proving such planets exist for one. That these planets are likely ubiquitous in the universe ( things which not everyone previously believed – or wanted to ) That previously unimaginable ( by humans anyway) planets such as Hot Jupiters existed too.

But in terms of representativeness the current sample is close to meaningless and also VERY small. There are no truly random samples . There won’t be before submicrosecond astrometry becomes available and is applied that we will begin to see a more accurate picture of planet frequency and type . Though even then, only in terms of mass and orbital dynamics for all but a small population of nearby targets that can be directly imaged. Gaia with its 20 micro arc second precision – especially after an extended ten year mission – will start this off and give a reasonably accurate census of Jupiter mass ( and bigger) planets out to Jupiter like orbits within about 500 parsecs. Microlensing from WFIRST will add to this too with a fairly random cohort of most planets within a few AU of all star types too. Then we will get a far better though far from complete picture of planet types and planetary architectures.

In terms of the availability bias consider this. The Earth has been seen as atypical by some authors for many reasons but to pick one at random – because of it’s Moon and said moon’s perceived unique properties . Unique compared to what ? The other moons in our own solar system . We have discovered NO moons outside of the solar system ( and not for the lack of trying ) . NONE and don’t appear close to doing so for some time. So how can the Moon possibly be described as somehow unique with a sample size of one ?

“The Habitable zone” is just theory. Not a hypothesis but a paradigm. Refined to describe a band around a star where temperatures allow liquid water to exist on the surface of a suitable

(terrestrial) planet. A planet orbiting a ‘sunlike star’ ( Liquid water as a requirement of life on Earth . So it is unavoidably subject to the anthropomorphic principle – however weak. )

Where it is applied to non Sun like M dwarfs the theory begins to break down. But as with most paradigms it is useful as we have to start somewhere ! As has also been pointed out here – it is not the “inhabited zone”. (more accurately – the inhabited by life as we know and recognise it zone) But it has become synonymous with that over time. To progress to the ( next ) level and become a bone fide hypothesis it needs to be successfully subject to challenges – falsifiability – as hypotheses must be to remain as such. Finding surface water on an Earth like planet in said zone of a Sun like star would support a hab zone hypothesis .

But this has not yet happened.

We don’t yet have any such evidence with which to test that hypothesis . Observationally anyway. Simulations , however sophisticated , can only be as good as the data fed into them . As well as being subject to the availability bias.

We already have a Mars in our system, why go 100 Parsecs to another one.

This system is likely twice the age of our own solar system. This

means that world has been subject to extensive flaring. We should be

able to measure diffraction levels in it’s atmosphere, with more advanced missions coming up. I will bet that it will show a minimal atmosphere. sure maybe 10x that of Mars, but that doesn’t get you anywhere, especially as it’s continually being lost to space.

You may ask, what about the dark side would not that have ice and maybe an Ocean under that. My answer: while it had a substancial atmosphere in it’s youth, it worked against habitability as it transferred heat pulses to darkside. Eventually even the dark side loses most of it’s water and much of any reservoirs of atmosphere. But as the atmospheric density decreases, so does the impact on the dark side and any ices there, a near equilibrium state ensues that retains an atmosphere of minimal consequence.

My opinion is that the only interesting worlds within M stars will be those with a Neptune sized(or larger) gas giants in the habitability zone with Large Moons orbiting the. Such moons would be protected by a magnetic field of the Neptune class planet. But such find would be rarer than a straight flush.

The idea that most of the dead M dwarf planet worlds might turn out to be true. I am wondering how much ozone the solar wind can strip so that life might not be able to permanently survive there or at least have a detectable spectral signature. Without ozone and oxygen, UV, EUV and X rays can’t be blocked. Some life could be there and we would not know it. Time will only tell.

Since Kepler 1649C was detected by Kepler with the transit method, so transmission spectroscopy could used on it by the JWST. I assume ground based telescopes should be able to do the same if there really is a planet there close to Earth’s size.

Like other people in lock down, just trying to stay in practice.

Habitability and habitable zones (HZs) are similar but distinct. For example,you can devise a measure such as a thermal belt around a star and designated that as the HZ with its inner and outer ring. But then you have a planet placed in that ring with corresponding internal and external parameters affecting the harshness or conduciveness to life that might prevail within its atmosphere, at its surface, ocean…caverns..

And we still might be differing as to whether we are talking about microbes or little green men. And the question might still rest on what epoch we are talking about.

Faced with all that, all we can do in response is search for more and more clues; model the stellar system in more and more detail or hypothesize a wider and wider range of planetary conditions.

When I think about this in terms of still turning over remaining rocks, the first thing that comes to mind, is what else can we extract from looking at Earth and the other terrestrial planets from deep space?

Voyager and Cassini did notable back glances, but the inferences often do not get past, “Gee, look at that small pale dot. Ain’t that something.” Perhaps there are some more chemical signals we should be looking at from a distance with our existing set of examples. It might influence our next generation of exoplanet telescopes.

The way that this planet was found – by double-checking the false positives predicted by their algorithm- is interesting indeed. We should now be seeing how many more Kepler planets we may have missed!

That said, as I’ve cautioned in the past, assessing an exoplanet’s habitability based on its current location within the habitable zone is almost meaningless, especially for those planets that orbit M-dwarf stars.

If this planet (Kepler-1649c) had formed in-situ as it orbits this mid-Mdwarf star (Teff ~3240 K; ~ M5), its pre-main-sequence habitable zone would have been located well past the location of 1649c for some tens of millions of years, triggering a runaway greenhouse for approximately that amount of time. This would have been sufficient to desiccate the surface of a planet with a much larger surface water inventory than the Earth. This does not even factor in atmospheric erosion during that early period of intense stellar radiation.

It is possible that the planet could have avoided the worst of this intense early period of hydrodynamic escape if it had formed in the outer stellar system and migrated inward at a later point in time, but this scenario becomes much less likely after the protoplanetary gas disk dissipates within the first few million years.

It is hard to conduct proper habitability analyses because they require knowledge of the initial conditions and subsequent planetary/stellar evolution, among other bits of information that are difficult to obtain. Nevertheless, we do know enough now to make semi-realistic analyses that will be improved with better upcoming atmospheric observations. My 2018 review paper (“A more comprehensive habitable zone for finding life on other planets”) discusses a more holistic approach to habitability assessment that can be tailored as we learn more about these planets.

Thanks Ramses,

Surely all this represents the ideal segue into a review of “Rare Earth” ? On the occasion of its twentieth anniversary. I can’t think of anyone better qualified !

Best wishes

Ashley

I second the thought. Ramses, I’ll send you a note via email.

Hi Paul and Ashley,

Thank you for considering me for this.. “Rare Earth” is one of my most favorite reads. I can’t believe it’s been 20 years since it first came out!

Isn’t the “Rare Earth” argument based on a lot more than habitability?

Rare Earth Hypothesis.

More importantly, it is about the existence of complex life (i.e. metazoa and plants) not about whether prokaryotic life is rare or not. The galaxy could be filled with planets bearing only single cell life that should be detectable by spectrographic observation.

Recent work suggests that multicellularity isn’t some lucky accident, but rather a natural development of communal living, e.g. bacterial biofilms. That the emergence of true complex life was coincident with the atmospheric level of O2, and that current aerobic metazoa requires a minimum O2 level in water or air to survive, seems to me supportive of the idea that complex life emerges when it becomes possible.

I do think Dr. Ramirez argument that the early stage of stellar evolution is important and may rule out some planets of M dwarfs that are currently in the HZ. But at worst this seems to reduce the likelihood of M dwarf planets being life-bearing, rather than other stellar types closer to our sun being able to bear life. Even M dwarf planets, once their star settles down could possibly reacquire an atmosphere from comet impacts.

I hope we don’t end up arguing on the semantics of what “rare” means.

Alex,

The rise of oxygen and its relation to complex life is a central topic in habitability studies (and is a potential biosignature gas as well). I discuss the rise of oxygen and the relationship between simple and complex life in my 2018 review paper. This is also an area that my own Ph.D. advisor (Jim Kasting) had focused on during his career. Moreover, with the surging interest in technosignatures, Ed Schwieterman and colleagues had recently taken the HZ concept and tailored it for the search for complex life. Without spilling the beans (too much), I’ll have a paper coming out soon that assesses this latter scenario some more. For complex life, it isn’t just the O2 partial pressure that’s important, but the concentrations of the other atmospheric gases as well.

I agree that complex life can arise once environmental conditions becomes suitable (e.g., habitability), but I also think we can make some headway on the relative frequency of simple vs complex life by exploring our own backyard. With upcoming missions to Mars, Titan, and other places, we can begin to test whether simple life is as common throughout the cosmos as Ward and Brownlee had argued.

I should look over your review paper again to get a better POV on your arguments and where you stand. Even if complex life is extremely rare, but single-cell life is much more common, if we can eventually get sample of such life, it will tell us a lot about the fundamentals of living biochemistry and molecular biology. Complex life will tell us a lot more about the evolution of phenotypes and ecosystems.

I look forward to reading your upcoming paper (please make sure Paul Gilster is made aware of it as soon as it is in preprint) as well as a possible CD article in due course.

Dr. Ramirez the concept of dynamic habitability is a fascinating subject and one area that is different in M dwarf systems is time and size scales.

The orbital speed and its size make for a much higher level of cometary impacts. These planets are speeding around their star at a pace of some 20 times faster then earth and in a very close orbit. The question is how long this refreshment of volatiles will last and that depends on the size and long lived dynamics of the cometary cloud. The effects of the greater bombardment will also cause a larger percentage of volatiles to be buried deeper in the planet’s mantle. What is your opinion on how this could affect these speeding worlds?

Searching for a cometary belt around Trappist-1 with ALMA.

https://arxiv.org/abs/1909.09158

Michael,

Simulations by folks like Sean Raymond and Jack Lissauer showed that cometary/asteroid impacts may be more intense on these speeding M-dwarf planets in these close-in orbits. This, according to them, would favor atmospheric erosion and a preferential loss of volatiles. However, my colleagues and I are revisiting this notion to see if we get these same results or different ones.

I glad to hear that your group is looking into this scenario. Something that could affect this is impacts on certain points of these tidally-locked worlds, just as our meteor showers peak at 2am. The larger earths to super earths with their high magnetic fields should give some protection from erosion and loss of volatiles. With something like the Carrington Event happening almost yearly (18 days) on these world there may be very large geoelectric fields induced in their lithospheres with interesting dynamic activity. The Younger Dryas (around 12,900 to 11,700 years BP) impacts are an examples of how these planets could keep the volatiles locked up in glacial deposits.

R. R.,

Reflecting on what you are saying about early phases of planetary existence ( vs. “life”) in a habitable zone: Would not the Earth as well experienced early cataclysmic conditions on its surface? After all, we assume a collision that resulted in the formation of the moon. But beside that the periods of bombardment, say three billion years ago, were not picnics either. It would seem that even though the Earth has spent most of its time in the HZ ring, until about the Cambrian era, it was not from our perspective a nice place to live.

wdk,

If Earth’s location (1 AU) had ever exhibited runaway greenhouse conditions, it happened very briefly near the very birth of the solar system, well before Earth became a mature planet. However, it took some ~50 – 60 Myr for Earth to fully accrete, with most of the supplied water likely coming towards the end of that period, when conditions were already relatively clement. Simply put, Earth never experienced the long and desiccating runaway greenhouse periods that may characterize many planets orbiting mid- to late M-stars.

After that point, there’s some evidence (from zircons) that Earth could have been quite habitable by 4.3 – 4.4 Ga. You are right that complex life did not arise until ~540 Myr ago (i.e., in the infamous Cambrian Explosion) but simple life had taken root by 3.8 Ga, if not earlier.

Wasn’t there some analysis that the Earth’s water was split between primordial water at formation, and water delivered by impacts?

Complex life appeared well before the Cambrian. The Cambrian is notable for the emergence (in the fossil record, e.g. the Burgess shales) of a number of basic body plans (phyla). So far the earliest metazoan found is about 610 my old, and the Ediacaran metazoans appearing in the period before the Cambrian, in the Proterozoic. Because of the nature of soft-bodied animals not fossilizing well, it wouldn’t surprise me if the earliest multicellular organisms didn’t appear even earlier. Dawkins (“The Ancestor’s Tale”) suggests that metazoa could have appeared at least as early as 1 bya based on the molecular clock, well into the Proterozoic.

Alex,

To clarify, some evidence suggests that some simpler metazoans arose before the Cambrian explosion (for instance: sponges, as I discuss in my review paper also), possibly predating the second rise of oxygen (~0.6 Gyr ago). However, most of the major body plans that produced the larger hardy organisms (what I had meant in my oversimplification above) appeared at the Cambrian explosion. From this and other considerations, one could conclude that oxygen may be a necessary, but insufficient, condition for complex life.

There was certainly some water accreted by Earth after it formed, but the argument is whether most of Earth’s water came in during or after accretion. Many believe that most of it was probably acquired during accretion. But there is still healthy debate here, with a recent idea (for instance) being that most of the water was delivered during the Moon-forming impact. Nevertheless, it makes sense that Earth was able to accrete the water it did during formation because it was not even in a runaway greenhouse state for most of that phase.

A lot of us grew up thinking that there were Nine Planets and it was doubtful we would live to see a new one discovered. Now there are Earth-sized, Earth-temperature planets falling through the cracks in algorithms! Everybody involved should give themselves a big pat on the back … then get back to poring over those files. :)

The orbital resonances described tie in with https://arxiv.org/pdf/1905.11419.pdf – simulations suggest the TRAPPIST-1 planets may induce persistent chaotic rotation in one another. As I understand it the rate they suggest is slow – in some ways perhaps “worse” than some resonances – but it is a different image from the usual Dayside and Nightside. What would the hydrology, the erosion patterns, even the plate tectonics and orogeny look like given random extremes of heat and cold? If the planet has an inner core with its own rotation like Earth, what would repeated shifts of rotation speed and axis do to the outer core and magnetic field?

I wonder if the results from astrometry missions, such as that of the Hipparcos satellite, might also be useful, as a check, to weed out false positives. Since astrometry missions’ purpose is to determine the precise positions of stars, multiple observations of a given star, over sufficiently long periods, could–within the limits of the instruments, and depending on the planets’ masses, and their orbit planes’ inclination(s) to the line of sight–detect the “wobble(s)” of the star (or its/their absence) at the proper time(s).

If astrometry missions like Hipparcos had the sensitivity to weed out false positives in the Kepler data we wouldn’t need transit surveys and could just rely on all planet astrometric data alone. Hipparcos reached a sensitivity level of milliarc seconds – unprecedented at the time and orders of magnitude better than could be achieved from the atmosphere swamped ground. However much the diligence of the observers such as poor old Peter Van de Kamp.

Ongoing Gaia should reach precision levels yet orders of magnitude better again. Perhaps below even 20 microarc seconds for brighter stars . Mind boggling, but still only enough to detect Jupiter mass and larger exoplanets orbiting between 3-5 AU ( according to how long Gaia can operate , circa 5-10 years) . Tens of thousands indeed. Perhaps even as small as Neptune mass for some close stars within ten parsecs or so. But still a long short of Earth mass and lower ( Mars sized) planets closer into their parent stars. That requires sensitivity approaching sub microarc second levels ( < 0.3) .

"Just" an order of magnitude improvement mind.

Currently the instrumentation required for this kind of performance is blighted by numerous systematic failures and technological immaturity . ( the recent ESA M class round 5 did not even short list the Theia astrometry telescope, which proposed sub microarc second astrometry of 50 nearby stars ) But I'm sure it will come soon and I'm confident we will see this over the next decade . Probably sticking with an "all planet" model survey of stars within fifty light years or so.

But not yet.

That said , if you go on the NASA ExoPag site , the latest meeting presentations include a small astrometric mission concept."Micro dot". A low budget ( <$50 million ) concept built around a commercial 0.35m off axis telescope and satellite bus , but capable of finding down to Earth sized planets within an AU of the ten nearest sunlike stars and within 2AU of the next twenty such stars .

I wasn’t suggesting that such new missions (and earth-based systems) not be developed, just that old missions’ data sets might be useful for purposes other than what their mission designers were seeking. (The Viking Orbiters’ weather observations–monitored on-site in real time by the Landers, which facilitated improvements in terrestrial weather forecasting [meteorologists tried their hand at forecasting Mars’ simpler weather]–is just one of myriad examples of data being used for purposes other than what the investigators had in mind.) Such “data re-purposing” is also very cheap, enabling it to serve as a “back-up” of sorts to missions that fail, or are cancelled (which no one [except some politicians] wants, but sometimes happens).

I would love to see an essay that applies what we have learned in the last 20 years to the Rare Earth hypothesis. We have learned so much in that time. I would especially like to see the role Earth’s moon plays in the Rare Earth function deconstructed.

On living planets orbiting red dwarfs. Perhaps watery super earths or mini Neptunes could evolve into living planets. These planets need to loose water to become more habitable. As the star ages, the planet would have to migrate inwards to maintain liquid surface water. There would only be a narrow range of star evolutions and planet water content combinations that would work. The crucial ingredient may be whether the planet migrates inwards.

Stay tuned, as such an essay may be in the works.

The Sun’s brightness grows by 7 percent every billion years, so the Sun was at least 20 percent dimmer 4.4 Ga ago which might reduce a greenhouse effect. However, Venus was in the life belt at that time which is why it is thought to have had an ocean which eventually evaporated and boiled off due to a runaway greenhouse effect when the Sun’s brightness increased for 2 billion years, and most of the water molecules were lost to space through solar wind stripping as shown by the 2:1 DH20 to H20 ratio compared to Earth. Venus has twice Earths deuterium water or heavy water.

The term runaway greenhouse effect is used for a planet not in the life belt, but inside it or too close to the star. I don’t see an Earth sized planet such as Keptler 1649C with a runaway greenhouse effect in pre-main sequence since the star would be dimmer at that time and the solar flaring and x rays would come after in early main sequence where any increased greenhouse effect would have to come into effect.

Also Keptler 1649 C is also potentially tidally locked which is a problem for a greenhouse effect since any water on the night side would be frozen reducing the amount of water in the atmosphere on the night side as Robert Flores has mentioned. The amount of water vapor in an atmosphere is dependent on pressure and temperature. Warm air holds more water vapor than cold air so the warmer temperature will always hold more water vapor. Hotter temperatures on average increase rainfall, and cloudiness. The cold night side would balance the temperature limiting the warmth of a greenhouse effect.

A tidally locked planet might have some tidal heating, and if it does that might increase the volcanism so a 1649C could still have an atmosphere and some greenhouse effect, but this is only a speculation, or only a potential, but still an unknown, but the spectra of Kepler 1649C should give us the gases and would help with an atmospheric model.

Nitrogen is essential for life, but N2 or molecular nitrogen has no dipole moment, so it has no rotational and vibrational transitions and therefore no spectral features in the visible and near infra red. If we can detect N20 or nitrous oxide with other biosignatures like methane, ozone and oxygen, then nitrogen must be there and life, the biosignatures of life. N2O does have a dipole moment. Nitrous oxide is part of the nitrogen cycle from bacteria or Nitrobacteria and Nitrosomonas Kiang, and other authors, 2018, Exoplanet Biosignatures. Kiang. Internet article.

I forgot about an red M dwarfs T Tauri phase which is premain sequence and more luminous which might cause a runaway greenhouse effect if the exoplanet is on the inner edge of the life belt today. Kepler 1649C gets 75 percent Earth’s sunlight, so the brightness of it’s star would have to go up 25 percent to equal Earths sunlight today which is not enough for a runaway greenhouse effect. Earth had a T Tauri phase, yet we still have an ocean. Even if there was a runaway greenhouse effect on Kepler 1649C to cause it to loose a lot of water, there still is the potential for tidal heating and volcansim to give it some more water from it’s interior. By now it would have lost a lot of water through solar wind stripping even if it did not have a runaway greenhouse effect. A spectral signature with water might be nice. A false positive of oxygen is always possible through the dissociation of hydrolysis of water molecules by EUV.

In the Hadean eon, Earth might have had a different beginning that Keptler 1649C, the giant impact hypothesis. The collision with Theia with Earth at a grazing angle blasted the entire mantle of Earth into outer space where it formed the Moon. Earth still was able to make an ocean and maybe some water has come from comets. The result of that collision might have caused Earth to loose some water. The collision might have gained some water from Earth’s interior because the entire surface and mantle was blasted off the Earth into outer space leaving a molten and exposed mantle which released some water and atmophiles. Volcanism might have given it some more water. Consequently, Earth might not be a completely accurate atmospheric model to understand Kepler 1649C if it does not have a Moon.

Just out, about waterworlds:

https://www.pnas.org/content/early/2020/04/15/1917448117