Is there a single technology that can take us from being capable of reaching space to actually building an infrastructure system-wide? Or at least getting to a tipping point that makes the latter possible, one that Nick Nielsen, in today’s essay, refers to as a ‘space breakout’? We can think of game-changing devices like the printing press with Gutenberg’s movable type, or James Watt’s steam engine, as altering — even creating — the shape and texture of their times. The issue for space enthusiasts is how our times might be similarly altered. Nick here follows up an earlier investigation of spacefaring mythologies with this look at indispensable technologies, forcing the question of whether there are such, or whether technologies necessarily come in clusters that enforce each other’s effects. The more topical question: What is holding back a spacefaring future that after the Apollo landings had seemed all but certain? Nielsen, a frequent author in these pages, is a prolific writer whose work can be tracked in Grand Strategy: The View from Oregon, and Grand Strategy Annex.

by J. N. Nielsen

1. Another Hypothesis on a Sufficient Condition for Spacefaring Civilization

2. The Nineteenth Century and the Steam Engine

3. The Twentieth Century and the Internal Combustion Engine

4. The Twenty-First Century and the Energy Problem

5. The World That Might Have Been: Accessible Fission Technology

6. Nuclear Rocketry as a Transformative Technology

7. Practical, Accessible, and Ubiquitous Technologies

8. The Potential of an Age of Fusion Technology

9. Indispensability and Fungibility

10. Four Hypotheses on Spacefaring Breakout

1. Another Hypothesis on a Sufficient Condition for Spacefaring Civilization

Civilization is the largest, the longest lived, and the most complex institution that human beings have built. As such, describing civilization and the mechanisms by which it originates, grows, develops, matures, declines, and becomes extinct is difficult. It is to be expected that there will be multiple explanations to account for any major transition in civilization. At our present state of understanding, the best we can hope to do is to rough out the possible classes of explanations and so lay the groundwork for future discussions that penetrate into greater depth of detail. It is in this spirit that I want to return to the argument I made in an earlier Centauri Dreams post about the origins of spacefaring civilization.

The central argument of Bound in Shallows was that, while being a space-capable civilization is a necessary condition of being a spacefaring civilization, an adequate mythology is the sufficient condition that facilitates the transition from space-capable to spacefaring civilization. According to this argument, the contemporary institutional drift of the space program and of our civilization is a result of no contemporary mythology being readily available (or, if available, such a mythology remains unexploited) to serve as the social framework within which a spacefaring breakout could be understood, motivated, rationalized, and justified.

In the present essay I will consider an alternative hypothesis on the origins of spacefaring civilization, again building on the fact that we are, today, a space-capable civilization that has not as of yet, however, experienced a spacefaring breakout. The alternative hypothesis is that a key technology is necessary to great transitions in the history of civilization, and that a key technology is like the keystone of an arch, which when present constitutes a stable structure that will endure, but, when absent, the structure collapses. Successful civilizations see a sequence of key technologies that are exploited at a moment of opportunity that allows civilization to internally revolutionize itself and so avoid stagnation. I will call this the technological indispensability hypothesis.

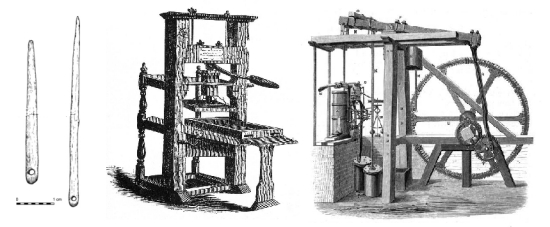

There are many key technologies that could be identified—the bone needle, agriculture, written language, the moveable type printing press—each of which represented a major turning point in human history when the technology in question was exploited to the fullness of its potential. We will take up this development relatively late in the history of civilization, beginning with the steam engine as the crucial technology of the industrial revolution, and therefore the technology responsible for the breakthrough to industrialized civilization.

[Indian & Primose Mills steam engine, built in 1884, in service until 1981]

2. The Nineteenth Century and the Steam Engine

The nineteenth century belonged to steam power, which both built upon previous technological innovations as well as laying the groundwork for the large-scale exploitation of later technologies. But it was steam power that enabled the industrial revolution, which was an inflection point in human agency, both in terms of human ability to reshape our environment and the human ability to harness energy for human use on ever-greater scales. Without the rapid adoption and large-scale exploitation of steam engine technologies for shipping, railways, resource extraction, and industrial production as the model for industrialized civilization, later technological developments (like the internal combustion engine or the electric motor) probably would not have been so effectively exploited.

Almost two hundred years of continuous development built on prior technologies from the earliest steam devices (not counting earlier steam turbines such as that of Hero of Alexandria, which was not a stepping stone to later developments building on this technology) to James Watt’s steam engine. A series of inventors, starting in the early seventeenth century—Giovanni Battista della Porta (1535-1615), Jerónimo de Ayanz y Beaumont (1553-1613), Edward Somerset, second Marquess of Worcester (1602-1667), Denis Papin (1647-1713), Thomas Savery (1650-1715), and Jean Desaguliers (1683-1744)—created steam-powered devices of increasing efficiency and utility. And, of course, while James Watt’s steam engine was the culmination of these developments, it was not an end point of design, but the point of origin of exponential technological improvements that followed.

The technology of the steam engine, then, could be construed as a key technology that enabled the industrial revolution. Previous labor-saving technologies—not only earlier forms of the steam engine as implied by the evolution of that technology, but also water mill and windmill technology known since classical antiquity—were limited by their inefficiency and by the sources of energy they harvested. The steam engine, once understood, was capable of increasing efficiency both through improved design and precision engineering, and it allowed human beings to tap into sources of energy sufficiently plentiful and dense that powered machine works could, in principle, be installed at almost any location and be operated continuously for as long as fuel could be supplied (which supply was facilitated by the energy density of the fuel, first coal for steam technologies, then oil for the internal combustion engine).

About fifty years after Watt’s later iterations of his steam engine design, Sadi Carnot published Réflexions sur la puissance motrice du feu et sur les machines propres à développer cette puissance (Reflections on the Motive Power of Fire and on Machines Fitted to Develop that Power, 1824), and in so doing systematically assimilated steam engine technology to the conceptual framework of science. It was this scientific understanding of what exactly the steam engine was doing that made it possible to improve the technology beyond the limits of tinkering (or what we might today call “hacking”). As we shall see, however, the full exploitation of a transformative technology seems to require both scientific development and practical tinkering.

In regard to my thesis in Bound in Shallows, mythologies present in the Victorian age that enabled the exploitation of steam technology could include the belief in human progress and belief in the distinctive institutions of Victorian society. To take the latter first, in The Victorian Achievement I argued that the ability for Victorian England to keep itself intact despite the wrenching changes wrought by the industrial revolution was key to the success of the industrial revolution: “[Victorian civilization] achieved nothing less than the orderly transition from agricultural civilization to industrialized civilization.”

At the same time that a civilization must internally revolutionize itself in order to avoid stagnation, it must also provide for continuity by way of some tradition that transcends the difference between past, present, and future. The ideology of Victorian society made this possible for England during the industrial revolution. A sufficiently large internal revolution that fails to maintain some continuity of tradition could result in the emergence of a new kind of civilization that must furnish itself with novel institutions or reveal itself as stillborn. If the population of a revolutionized civilization cannot be brought along with the radical changes in social institutions, however, the internal revolution, rather than staving off stagnation, simply becomes an elaborate and complex form of catastrophic failure in which a society approaches an inflection point and cannot complete the process, coming to grief rather than advancing to the next stage of development.

It has become a commonplace of historiography that nineteenth century Europe, and Victorian England in particular, believed in a “cult of progress”; the studies on this question are too numerous to cite. A revisionary history might seek to overturn this consensus, but let us suppose this is true. If belief in progress distinctively marked the nineteenth century engagement with the earliest industrial technologies, we can regard this as an antithetical state of mind to what Gilbert Murray called a “failure of nerve” [1], and as such a steeling of nerve may have been what was necessary for a previously agricultural economy to find itself rapidly transformed into an industrialized economy and to survive the transition intact.

At this point, we can equally well argue for the indispensability of technology or the indispensability of mythology in the advent of a transformation in civilization, but now we will pass over into further developments of the industrial revolution. After the age of the steam engine, the twentieth century belonged to the internal combustion engine burning fossil fuel. It was the internal combustion engine that drove technological and economic modernity first revealed by steam technology to new heights.

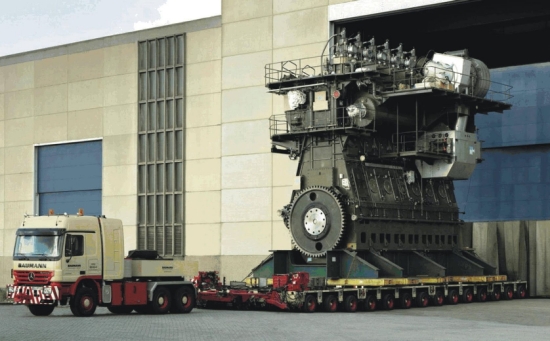

[The Wärtsilä-Sulzer RTA96-C internal combustion engine]

3. The Twentieth Century and the Internal Combustion Engine

The key technology of the twentieth century, and the successor technology to the steam engine, was the internal combustion engine. The first diesel engine was built in 1897, and the diesel engine rapidly found itself employed in a variety of industrial applications, especially in transportation: shipping, railroads, and trucking. Two-stroke and four-stroke gasoline engines converged on practical designs in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century and began to replace steam engines in those applications where diesel engines had not already replaced steam.

The internal combustion engine has a fuel source that can be stored in bulk (also true for steam engines), and it is scalable. The scalability of the internal combustion engine often goes unremarked, but it is the scalability that ensured the penetration of the internal combustion engine into all sectors of the economy. An internal combustion engine can be made so small and light that it can be carried around by one person (as in the case of a yard trimmer) and it can be made so large and powerful that it can used to power the largest ships ever built. [2] The internal combustion engine is sufficiently versatile that it can be dependably employed in automobiles, trucks, trains, ships, power generation facilities, and industrial applications.

While it would be misleading to claim that the internal combustion engine was revolutionary to the degree that the steam engine was revolutionary, it would nevertheless be accurate to say that the internal combustion engine allowed for the expansion and consolidation of the industrialized civilization made possible by the steam engine.

The internal combustion engine proliferated at a time when the belief in the institutions of societies undergoing industrialization weakened and arguably has never recovered, so that it would be difficult to argue that the ongoing industrial revolution was driven by a distinctive mythology, whereas the continued development and refinement of the crucial technologies of industrialization continued to advance even as the core mythologies of industrializing societies were questioned as never before. At this point, technology looks more indispensable to ongoing industrialization than does mythology.

The experience of the First World War was a turning point both in technology and social change. I have called the First World War the First Global Industrialized war; for the first time, the war effort was existentially dependent upon fossil fuel powered trains, trucks, motorcycles, aircraft, and tanks, which transformed the experience of combat, so that German soldiers thereafter spoke of the “frontline experience” (Fronterlebnis). Even while all traditional warfighting seemed to vanish as being irrelevant (heroic cavalry charges no longer carried the day or turned the tide), a new kind of industrialized war experience appeared, and we can find this experience not merely described but celebrated by Ernst Jünger in Storm of Steel, Copse 125, and other works.

The war led to the destruction of many political regimes in Europe that had endured for hundreds of years, and saw the appearance of radical new regimes like Soviet Russia, which emerged from the wreckage of Tsarist Russia, which could trace its origins back almost a millennium. Whether these ancient regimes were the victims of a mythology that catastrophically failed in the midst of industrialized warfare, or whether the failed regimes brought down traditional mythologies with them, is probably a chicken-and-egg question. But even as ancient regimes and their associated mythologies failed, technology triumphed, and with technology there arose new forms of human experience, the principal driver of which new experiences was continued technological innovation.

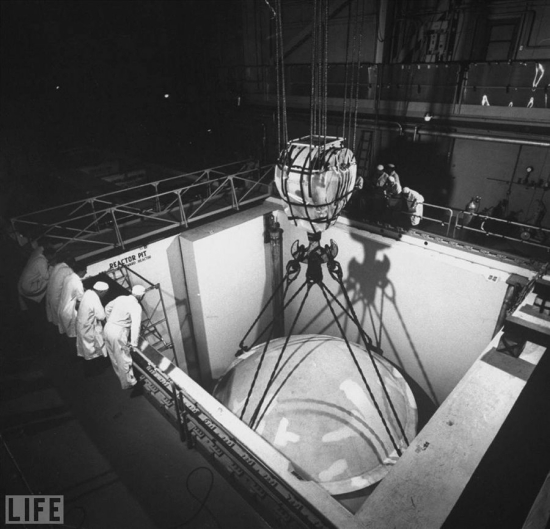

[Reactor dome being lowered into place at Shippingport Atomic Power Station in Pennsylvania]

4. The Twenty-First Century and the Energy Problem

Both steam engines and internal combustion engines exploited the energy of fossil fuels. What economists would call the negative externalities of the trade in fossil fuels that grew in the wake of the adoption of the internal combustion engine included the “resource curse,” which marred the political economy of many nation-states that possessed fossil fuels, and extensive pollution resulting from the extraction, refining, transportation, and consumption of fossil fuels. No one could have guessed, at the beginning of the twentieth century (much less at the beginning of the nineteenth century), the monstrosity that fossil fueled internal combustion engines would become, and, by the time our civilization was utterly dependent upon the internal combustion engine, it was too late to do anything except to attempt to mitigate the damage of the entire energy infrastructure than had been created to fuel our industries.

Having realized, after the fact, the dependency of industrialized civilization upon fossil fuels, we find ourselves and our society dependent upon industries that have high energy requirements, but lacking the technology to replace these industries at scale. We are trapped by our energy needs.

I am not going to attempt to summarize the large and complex issues of the advantages and disadvantages of energy alternatives, as countless volumes have already been devoted to this topic, but I will only observe that an abundant and non-polluting source of energy is necessary to the continued existence of technological civilization. We can have civilization without abundant and non-polluting sources of energy, but it will not be the energy-profligate civilization we know today. If energy is non-abundant, it must be rationed; and if energy is polluting, we will gradually but inevitably poison ourselves on our own wastes. Both alternatives are suboptimal and eventually dystopian; neither lead to future transformations of civilization that transcend the past by attaining greater complexity.

Just as there are those who argue for the continuing exploitation of fossil fuels without limit, and who appear to be prepared to accept the consequences of this unlimited use of fossil fuels, there are also those who argue for the abandonment of fossil fuels without any replacement, so that our fossil fuel dependent civilization must necessarily come to an end. Among those who argue for the abolition of energy-intensive industry, we can distinguish between those who advocate the complete abolition of technological civilization (Ted Kaczynski, John Zerzan, Derrick Jensen) and those who look toward a kind of “small is beautiful” localism of “eco-communalism” [3] that would preserve some quality of life features of industrialized civilization while severely curtailing consumerism and mass production.

Human beings would accept sacrifices on this scale, including sacrificing their energy demands, if they believed their sacrifice to be meaningful and that it contributed to some ultimate purpose (or what Paul Tillich called an “ultimate concern”). In other words, a sufficient mythological basis is necessary to justify great sacrifices. We have seen intimations of this level of ideological engagement and call to sacrifice with the most zealous environmental organizations, such as Extinction Rebellion — the “Red Brigade” protesters present themselves with a theatricality that is certain to attract some while repelling others; I personally find them deeply disturbing—which cultivates a quasi-religious intensity among its followers. It is unlikely that those who came to maturity within a technological civilization fully understand what the implied sacrifices would entail, but that is irrelevant to the foundation of the movement; if the movement were to be successful, the eventual regret of those caught up in it would not arrest the progress of a new ideology that sweeps aside all impediments to its triumph.

The proliferation of environmental groups since the late twentieth century (the inflection point is often given as being the publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring in 1962) demonstrates that this is a growing movement, but it is not clear that the most zealous groups can seize the narrative of the movement and become the focus of environmental activism. If, however, individuals were inspired by a quasi-religious zealotry to sacrifice energy-intensive living, we cannot rule out the possibility that the intensity of environmental belief could pave the way, so to speak, toward a transformative future for civilization that did not involve energy resources equal to or greater than those in use at present.

Energy resources equal to or greater than those in use today are crucial to any other scenario for the continuation of civilization. In the same way that eight billion or more human beings can only be kept alive by a food production industry scaled as at present, and to tamper with this arrangement would be to court malnutrition and mass starvation, so too eight billion human beings can only be kept alive by an energy industry scaled as at present, and to tamper with this arrangement would be to court disaster. This disaster could be borne if everyone possessed a burning faith in the righteousness of energy sacrifice, but in planning for the needs of mass society we may need to eventually recognize mass conversion experiences, but such cannot be the basis of policy; there is no way to impose this kind of belief.

One of the persisting visions of a solution for the energy problem of the twenty-first century is widely and cheaply available electricity that can be used to power electrical motors that would replace the fossil fueled engines that now power our industrialized economy. Throughout the nineteenth century dominance of the steam engine and the twentieth century dominance of the internal combustion engine, electric motors were under continual development and improvement. Electric motors came into wide use in industrial applications in the twentieth century, and into limited use for transportation, especially in streetcars when electrical power could be supplied by overhead lines. This can and has been done for longer distance electric railways as well, but the added infrastructure cost of not only laying track, but also constructing the electrical power distribution lines limited electrical train development. For ships and planes, electrical power has not been practicable to date. Only now, in the twenty-first century, are electrical technologies advancing to the point that electrical aircraft may become practical.

The problem is not electrical motors, but the electricity. Providing electricity at industrial scale is a challenge, and we meet that challenge today with fossil fuels, so that even if every form of transportation (automobiles, buses, trucks, shipping, trains, aircraft, etc.) were converted to electrical motors, the electricity grid supplying the electrical needs for these applications would still involve burning fossil fuels. A number of well-heeled businesses have recognized this and installed solar power panels on the roofs of their garages so that their well-heeled employees can plug in their electric cars while they work. This is an admirable effort, but it is not yet a solution for transportation at the scale demanded by our civilization.

If the electrical grid could either be developed in the direction of highly distributed generation with a large number of small electricity sources feeding the grid (which could well be renewables), or a continuation of the centralized generation model but without the fossil fuel dependency of coal, oil, and natural gas generating facilities, the use of electricity as the primary energy for industrial processes could be achieved with a minimum of compromises (primarily those compromises entailed by the difficulty of storing electricity, i.e., the battery problem). What would replace centralized generation if fossil fuel use were curtailed? There is the tantalizing promise of fusion, but before this technology can supply our energy needs, it would have to be shown to be practicable, accessible, and ubiquitous, which is an achievement above and beyond proof-of-concept for better-than-break-even fusion. At present, there seem to be few alternatives to nuclear fission.

The twenty-first century energy problem is the problem of the maintenance of the industrialized civilization that was built first upon steam engines and then upon the internal combustion engine; it is partially a problem of the direction our civilization will take, but it is not a problem of managing a transformative technology and the social changes driven by the introduction of a transformative technology. The initial introduction of powered machinery was such a transformative technology, but the ability to continue the use of powered machinery is no longer transformative, merely a continuation of more of the same.

It is as though we find ourselves, in the early twenty-first century, groping in the dark for a way forward. There is no clear path for the direction of civilization (which would include a clear path to energy resources commensurate with our energy-intensive civilization), and no consensus on defining a clear path forward. This absence of a clear path forward can be construed as a mythological deficit, or as the absence of a crucial technology. Here, I think, the balance of the argument favors a mythological deficit, because we possess nuclear technology, but no mythology surrounds the use of nuclear technology that would rationalize and justify its use at industrial scale—or, at least, no mythology sufficiently potent to overcome the objections to nuclear power.

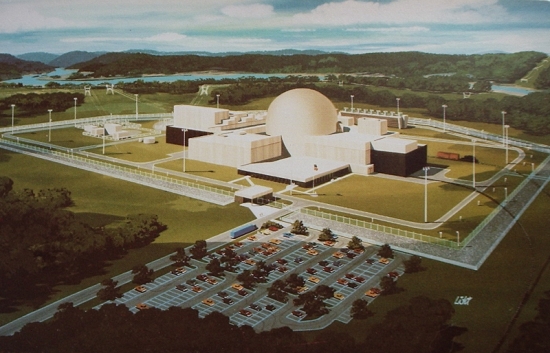

[The unbuilt Clinch River Breeder Reactor Project (CRBRP)]

5. The World That Might Have Been: Accessible Fission Technology

One of the potential answers to the twenty-first century energy problem is nuclear power, but nuclear power is one of many nuclear technologies, and nuclear technologies taken together, had they been exploited at scale, might have been a transformative technology, both for the maintenance of industrialized civilization without fossil fuels, as well as for the transformation of our planetary industrialized civilization into a spacefaring civilization. Submarines and aircraft carriers are now routinely powered by fission reactors, and it would be possible to engineer fission reactors for railways and aircraft. Ford once proposed the Nucleon automobile, but this level of fission miniaturization is probably impractical. But the nuclearization of our infrastructure has stagnated. Once ambitious plans to build hundreds of nuclear reactors across the US were scrapped, and instead we find new natural gas generating plants under construction.

Darcy Ribeiro wrote of a “thermonuclear revolution” as one of many technological revolutions constituting civilizational processes that are, “…transformations in man’s ability to exploit nature or to make war that are prodigious enough to produce qualitative alterations in the whole way of life of societies.” [4] But if we do recognize thermonuclear technologies as revolutionary, we cannot identify them as having fulfilled their revolutionary function because of the stagnation of nuclearization. The promise and potential of nuclear technology never really got started, despite plans to the contrary.

While there were plans for the nuclear industry to be a major sector of the US economy, and these plans were largely derailed by construction costs that spiraled due to regulation, the nuclear industry thus conceived and thus derailed was always to be held under the watchful eye of the government and its nuclear regulation agencies. After the construction of nuclear weapons, it was too late to put the nuclear genie back in the bottle, but if the genie couldn’t be put back in the bottle, it could be shackled and placed under surveillance. The real worry was proliferation. If fissile materials become easily available, other nation-states would possess nuclear weapons sooner rather than later, and the post-war political imperative was to bring into being a less dangerous world. A world in which nuclear weapons were commonplace would be a far more dangerous world than that which preceded the Second World War, so that despite the division of the world by the Cold War, the one policy upon which almost all could agree was the tight control of fissile materials, hence the de facto constraints placed upon nuclear science, nuclear technology, and nuclear engineering. [5]

The human factor in technological development is essential, as in mythology. The details of a mythology may speak to one person and not another. So, too, a particular technological challenge may speak to one person and not to another. For those who might have had a special bent for nuclear technologies, their moment never arrived. At least two generations, perhaps three generations, of scientists, technologists, and engineers who would have dedicated their careers to the emerging and rapidly changing technology of nuclear rocketry and the application of nuclear technology to space systems, had to find another use for their talents. These careers that didn’t happen, and lives that didn’t unfold, can never be measured, but we should be haunted by the lost opportunity they represent. And perhaps we are haunted; this silent, unremarked loss would account for institutional drift and national malaise (i.e., stagnation) as readily as the absence of a mythology.

Even benign nuclear technologies that do not directly involve fissionable materials have suffered due to their expense. When funding for the SSC was cancelled (after an initial two billion had been spent), an entire generation of American scientists have had to go to CERN in Geneva because that is where the instrument is that allows for research at the frontiers of fundamental physics. There is only this single facility in the world for research into fundamental particle physics at the energy levels possible at the LHC. The expense of nuclear science has been another strike against its potential accessibility. Funding for scientific research is viewed as a zero-sum game, in which a new particle accelerator is understood to mean that another device does not get funded. Sabine Hossenfelder’s tireless campaign of questioning the construction of ever-larger particle accelerators takes place against this background of zero-sum funding of scientific research. But if science were growing exponentially, as industry grew exponentially during the industrial revolution, there would be few (or, at least, fewer) conflicts over funding scientific research.

Not only are nuclear technologies politically dangerous and expensive, nuclear technologies are also physically dangerous; extreme care must be taken so that nuclear materials do not kill their handlers. The “demon core” sphere of plutonium, which was slated to be the core of another implosion nuclear weapon (tentatively scheduled to be dropped August 19, but the Japanese surrendered on August 15), was responsible for the deaths of Harry Daghlian (due to an incident on 21 August 1945) and Louis Slotin (due to an incident on 21 May 1946) as they tested the core’s criticality. Fermi had warned Slotin that he would be dead within a year if he failed to maintain safety protocols, but apparently there was a certain thrill involved in “tickling the dragon’s tail.” The bravado of young men taking risks with dangerous technology is part of the risk/reward dialectic. Daghlian and Slotin were nuclear tinkerers, and it cost them their lives.

Generally speaking, industrial technologies are dangerous. The enormous machines of the early industrial revolution sometimes failed catastrophically, and took lives when they did so. Sometimes steam boilers exploded; sometimes trains jumped their tracks. Nuclear technologies are subject to dangers of this kind, as well as the unique dangers of the nuclear materials themselves. Because of this extreme danger—partly for reasons of personal safety, and partly for reasons of proliferation, which can be understood as social safety—nuclear reactors have developed toward a model of sealed containers that can operate nearly autonomously for long periods of time. [6] This limits hands-on experience with the technology and the ability to tinker with a functioning technology in order to improve efficiency and to make new discoveries.

There is a kind of dialectic in the development of technology since the development of scientific methods, such that the most advanced science of the day allows for new technological innovations, but once the technological innovations are made available to industry, thousands, perhaps tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of individuals using the technology on a daily basis leads to a level of familiarity and practical know-how, which can then be employed to fine tune the use of the technology, and sometimes can be the basis of genuine technological innovations. Scientists design and build the prototypes of the technology, but engineers refine and improve the prototypes in industrial application, and this is a process more like tinkering than like science. So while the introduction of scientific method in the development of technology results in an inflection point in the development of technology (which is what the industrial revolution was), tinkering does not necessarily disappear and become irrelevant.

Because of the dangers of nuclear technologies, there is very little tinkering that goes on. Indeed, I suspect that the very idea of “nuclear tinkering” would send shudders down the spine of regulators and concerned citizens alike. And yet, it would be nuclear tinkering with a variety of different designs of nuclear rockets that would lead to a more effective and efficient use of nuclear technologies. As we noted with the steam engine, incremental improvements were made throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries until the efficiency of James Watt’s steam engine became possible, and most of this was the result of tinkering rather than strictly scientific research, as the science of steam engines was not made explicit until Carnot’s book fifty years after Watt’s steam engine. In the case of nuclear technology, the fundamental science was accomplished first, and only later was that science engineered into specific nuclear technologies, which may be one of the factors that has limited hands-on engagement with nuclear technologies.

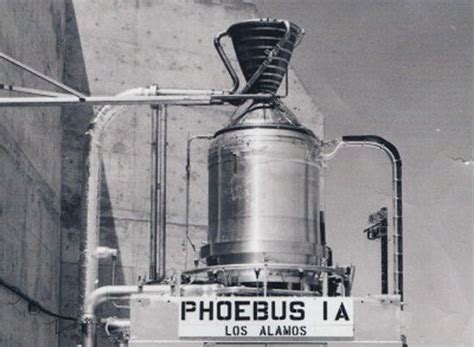

[Phoebus 1 A was part of the Rover Program to build a nuclear thermal rocket.]

6. Nuclear Rocketry as a Transformative Technology

Suppose that, for any spacefaring civilization, the key and indispensable technology is nuclear rocketry, or, we can say more generally, nuclear technology employed in spacecraft. Whether nuclear technology is employed in nuclear rockets, or in order to deliver megawatts of power in a relatively small package (e.g., to power an ion thruster), the use of nuclear fission could be a key means of harnessing of energies on a scale to enable space exploration with an accessible technology.

In what way is nuclear technology accessible? Human civilization has been making use of nuclear fission to generate electrical power (among other uses) for more than fifty years, all the while as research into nuclear fusion has continued. Nuclear fusion is proving to be a difficult technology to master. A century or two may separate the practical utility of fission power and fusion power. In historiographical terms, fission and fusion technologies may find themselves separated each into distinct longue durée periods — an Age of Fission and, later, an Age of Fusion. That means that nuclear fission technology is potentially available and accessible throughout a period of history during which nuclear fusion technology is not yet available or accessible.

How much could be achieved in one or two hundred years of unrestrained development of nuclear fission technology and its engineering applications? With an early spacefaring breakout, this could mean one or two hundred years of building a spacefaring civilization, all the while refining and improving nuclear fission technology in a way that is only possible when a large number of individuals are involved in an industry, with, say, two or more nuclear rocket manufacturers in competition, each trying to derive the best performance from their technology.

We know that the ideas were available in abundance for the exploitation of nuclear technology in space exploration. The early efflorescence of nuclear rocket designs has been exhaustively catalogued by Winchell Chung in his Atomic Rockets website, but this early enthusiasm for nuclear rocketry became a casualty of proliferation concerns. However, the imagination revealed early in the Atomic Age demonstrates that, had the opportunity been open, human creativity was equal to the challenge, and had this industry been allowed to grow, to develop, and to adapt, the present age would not have been one of stagnation.

In a steampunk kind of way, a spacefaring civilization of nuclear rocketry would in some structural ways resemble the early industrialized civilization of steam power. The nineteenth century industrial revolution was made possible by enormous machinery—steamships, steam locomotives, steam shovels (which made it possible to dig the Panama Canal), etc. A technological civilization that projected itself beyond Earth by nuclear rocketry would similarly be attended by enormous machinery. While fission reactors can be made somewhat compact, there are lower limits to practicality even for compact reactors, so that technologies enabled by the widespread exploitation of fission technology would be built at any scale that would be convenient and inexpensive. Nuclear powered spacecraft could open up the solar system to human beings, but these craft would likely be large and require a significant contingent of engineers and mechanics to keep them functioning safely and efficiently, much as steam locomotives and steamships required a large crew and numerous specializations to operate dependably.

[The bone needle, the moveable type printing press, and the steam engine]

7. Practical, Accessible, and Ubiquitous Technologies

We can summarize the technological indispensability hypothesis such that being a space-capable civilization is a necessary condition of being a spacefaring civilization, but a crucial spacefaring technology is the sufficient condition that facilitates the transition from space-capable to spacefaring civilization. What makes a spacefaring technology a sufficient condition for the transition from space-capable to spacefaring civilization is its practicality, its accessibility, and its ubiquity. A practical technology accomplishes its end with a minimum of complexity and difficulty; an accessible technology is affordable and adaptable; ubiquitous technologies are widely available with few barriers to acquisition. Stated otherwise, practical technologies don’t break down; accessible technologies can be repaired and modified; ubiquitous technologies are easy to buy, cheap, and plentiful.

Given the technological indispensability hypothesis, we can account for the drift of contemporary technological civilization by the absence of a key technology that would have allowed our civilization to take its next step forward, and we can further identify one technology—nuclear rocketry—as the absent key technology that, had it been exploited at the scale of steam engines in the nineteenth century or internal combustion engines in the twentieth century, would have resulted in a spacefaring breakout, and therefore a transformation of civilization.

None of this is inevitable, however. The mere existence of a technology is not, in itself, sufficient for a technology to transform a society. Some technologies, probably most technologies, are not intrinsically transformative. Of those technologies that are transformative, not all of these technologies have the potential to be practical, accessible, and ubiquitous. Of those technologies that are socially transformative and are practical, accessible, and ubiquitous, not all are sufficiently widely adopted to result in a transformational impact.

The list of technologies I cited earlier—among them, the bone needle, moveable type printing, and the steam engine—all were technologies that were transformative as well as being practical, accessible, and ubiquitous. The bone needle allowed for sewing form-fitting clothing during the last glacial maximum, therefore making it possible for human beings to expand across the entire surface of Earth. Movable type printing made books and pamphlets inexpensive and resulted in the exponential growth of knowledge; without inexpensive books and journals, the scientific revolution would not have made the impact that it did. Steam engines made the industrial revolution possible.

However, the existence of the technology alone is not sufficient; stated otherwise, it is not inevitable that a technology that is transformative will have the social impact that some of these technologies have had. The Chinese independently developed moveable type printing, and while this technology was in limited use, it did not revolutionize Chinese society. Chinese society stagnated in spite of possessing movable type printing technology. There are many possible explanations for this, first and foremost, the Chinese language itself may have required too many characters for movable type printing to be as effective a technology as it was for languages employing phonetic symbols with a smaller character set. In other words, the transformative technology of movable type printing may not have been practical and accessible using the Chinese character set; clearly it did not achieve ubiquity.

The example of the role of the Chinese language [7] in idea diffusion points to the possibility that a sequence of technologies (language is a technology of communication) may have to unfold in a particular order, with a civilization at each developmental juncture adopting a particular key technology (for linguistic technology, this might be a syllabary or a phonetic script), in order for later transformative events in civilization to occur. Formulated otherwise, transformative changes in civilization, like the industrial revolution, or a spacefaring breakout if that were to occur, may be metaphorically compared to inserting a key into the lock, such that each successive tumbler must be positioned in a particular way in order to finally unlock the mechanism.

In light of the above, we can reformulate the technological indispensability thesis such that a key spacefaring technology is the sufficient condition that facilitates the transition from space-capable to spacefaring civilization, but this crucial spacefaring technology must supervene upon the adoption of earlier technologies that facilitate and serve as the foundation for later spacefaring technology. We can call this the strong technological indispensability hypothesis, as it refers to technology alone as the transformative catalyst in civilizational change. The fact that the existence a technology alone does not inevitably result in its industrial exploitation once again points to the role of social factors—what I would call a sufficient mythological basis for the exploitation of a technology. In a weak formulation of the technological indispensability hypothesis, a sequence of technologies must be available, but it is a mythological trigger that leads to their exploitation. Here technology is still central to the historical process, but it must be supplemented by mythology. If we take this mythological supplement to be the sufficient condition for a spacefaring breakout, then we are back at the argument I made in Bound in Shallows.

We needn’t, of course, focus on any single causal factor, such as technology. It may be both the absence of a key technology and the absence of a key mythology. Just as the absence of a mythology may have been a factor that kept the technology from being exploited, the absence of the technology may have been a factor in limiting the mythological elaboration of its role in society. Much that I have written above about technology could be applied, mutatis mutandis, to mythology: a key mythology may need to develop organically out of previous mythologies, so that if a particular mythological tradition is absent, or develops in a different way, it cannot become the mythology that would superintend the expansion of a civilization beyond Earth. Moreover, these developments in technology and mythology may need to occur in parallel, so that it is like two keys inserted into two locks, each lining up each successive tumblers in a particular orientation—like launching a nuclear missile.

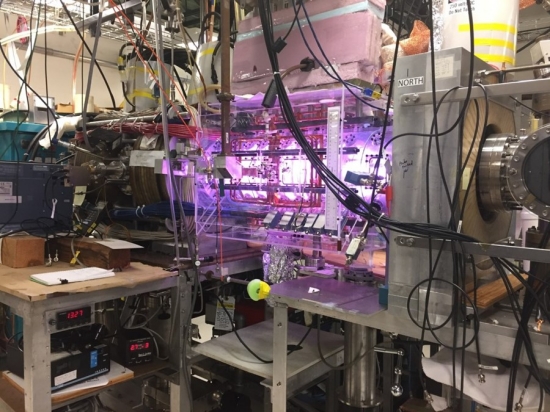

[Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory, PFRC-2]

8. The Potential for an Age of Fusion Technology

Can we skip a stage of technological development? Can we make the transition directly from our fossil-fueled economy to a fusion-based economy, without passing through the stage of the thermonuclear revolution? Or should we regard the development of fusion technologies to be an extension of, and perhaps even the fulfillment of, the thermonuclear revolution?

Part of the promise of fusion is that it does not require fissile materials and so does not fall under the interdict that cripples the development of fission technologies, but fusion technology is not without its dangers; the promise of fusion technology is balanced by its problems. One can gain an appreciation of the complexity and difficulty of fusion engineering from a pessimistic article by Daniel Jassby, “Fusion reactors: Not what they’re cracked up to be,” which, in addition to discussing the problems of making fusion work as an energy source, also notes that the neutron flux from deuterium-tritium fusion could be used to enrich uranium 238 into plutonium 239, so that fusion does not eliminate the nuclear proliferation problem (although, presumably, continued tight control of uranium could obtain similar non-proliferation outcomes as is today the case with fission). Of course, for every pessimist there is an optimist, and there are plenty of optimists for the future of fusion.

While fusion technology would not necessarily involve fissionable material, and therefore would facilitate the construction of nuclear weapons to a lesser degree than fission technologies, the capabilities that widespread exploitation of fusion technology would put into the hands of human beings would scarcely be any less frightening than nuclear weapons. In this sense, the problem of nuclear weapons proliferation is only a stand-in for a more general problem of proliferation that follows from any technological advance, as any technology that enhances human agency also enhances the ability of human beings to wage war and to commit atrocities. Biotechnology, for example, also places potentially catastrophic powers into the hands of human beings. Nuclear weapons finally pushed human agency over the threshold of human extinction and so prompted a response—international non-proliferation efforts—but this problem will re-appear whenever a technology reaches a given level of development. Will each successive technological development that pushes human agency over the threshold of human extinction provoke a similar response? And is this a mechanism that limits the technological development of civilizations generally, so that this can be extrapolated as a response to the Fermi paradox?

It may be possible that humanity skips the stage of development that would have been represented by the widespread exploitation of thermonuclear technology (here understood as fission technologies), but this skipping a stage comes with an opportunity cost: everything that might have been achieved in the meantime through thermonuclear technologies is delayed until fusion technologies can be made sufficiently practical, accessible, and ubiquitous. But because of the severe engineering challenges of fusion, the mastery of fusion technology will greatly enhance human agency, and as such it will eventually suggest the possibility of human extinction by means of the weaponization of fusion technologies, and so bring itself under a regime of tight control that would ensure that fusion technologies never achieve a transformative role in civilization because it never becomes practical, accessible, and ubiquitous.

[Mercury-vapor, fluorescent, and incandescent electrical lighting technologies]

9. Indispensability and Fungibility

The technological indispensability hypothesis implies its opposite number, which is the technological fungibility hypothesis: no technology, certainly no one, single technology, is the key to a transformative change in civilization. But what does it mean for a technology to be one technology? Are there not classes of related technologies? How do we distinguish technologies or classes of technologies?

One could argue that some particular technology is necessary to advance a civilization to a new stage of complexity, but that the nature of technology is such that, if one technology is not available (i.e., some putatively key technology is absent), some other technology will serve as well, or almost as well. If we cannot build nuclear rockets due to proliferation concerns, then we can build reusable chemical rockets and ion thrusters and solar sails. Under this interpretation, no single technology is key; what matters is how effectively some given technology is exploited.

Arguments such as this appear frequently in discussions of the ability of civilization to be rebuilt after a catastrophic failure. Some have argued that our near exhaustion of fossil fuels means that if our present industrialized civilization fails, there will be no second chance on Earth for a spacefaring breakout, because fossil fuels are a necessary condition for industrialization (and, by extension, a necessary condition for fossil fuel technologies like steam engines and internal combustion engines that are key technologies for industrialization). We have picked the low-hanging fruit of fossil fuels, so that any subsequent industrialization would have to do without them. [8]

In order to do justice to the technological fungibility hypothesis it would be necessary to formulate a thorough and rigorous distinction between technologies and engineering solutions to technological problems. This in turn would require an exhaustive taxonomy of technology. Is electric lighting a technology, while mercury-vapor lamps and fluorescent bulbs are two distinct engineering solutions to the same technological problem, or do we need to be much more specific and identify incandescent light bulbs as a single technology, with the different materials used to construct the filament being distinct engineering solutions to the technological problems posed by incandescent bulb design? If the latter, is electrical lighting then a class of technologies? Should we distinguish fungibility within a single technology (i.e., the diverse engineering expressions of one technology) or within a class of technologies? Without such a technological taxonomy, we are comparing apples to oranges, and we cannot distinguish between technological indispensability and technological fungibility.

These arguments about the fungibility of technology in industrialization also points to a parallel treatment for mythology: mythologies, too, may be fungible, and if a given mythology is not available in a culture, another could serve the same function as well.

[Wilhelm Windelband, 1848-1915]

10. Four Hypotheses on Spacefaring Breakout

We are now in a position to distinguish four hypotheses for an historiographical explanation for a spacefaring breakout, and, by extension, for other macrohistorical transformations of civilization (beyond a narrow focus on spacefaring mythology and spacefaring technology):

- The Mythological Indispensability Hypothesis: a key mythology is a sufficient condition for a transformation of civilization.

- The Mythological Fungibility Hypothesis: some mythology is a sufficient condition for a transformation of civilization, but there are many such peer mythologies.

- The Technological Indispensability Hypothesis: a key technology is a sufficient condition for a transformation of civilization.

- The Technological Fungibility Hypothesis: some technology is a sufficient condition for a transformation of civilization, but there are many such peer technologies.

Each of these hypotheses can be given a strong form and a weak form, yielding eight permutations: strong permutations of the hypotheses are formulated in terms of a single cause; weak permutations of the hypotheses are formulated in terms of multiple causes, though one cause may predominate.

I began this essay with the assertion that civilization is the largest, the longest lived, and the most complex institution that human beings have built. This makes maintaining any hypothesis about civilization difficult, but not, I think, impossible. We cannot grow civilizations in the laboratory, and we cannot experiment with civilizations in any meaningful way. However, we can learn to observe civilizations under controlled conditions, even if we cannot control what will be the dependent variable and what the independent variable.

History is the record of controlled observation of civilization (or an implicit attempt at such), but history leaves much to be desired in terms of scientific rigor. Explicitly coming to understand history as a controlled observation of civilization would require a transformation of how history is pursued as a discipline. The conceptual framework required for this transformation does not yet exist, so we cannot pursue history in this way at the present time, but we can contribute to the formulation of the conceptual framework that will make it possible to pursue history as the controlled observation of civilization in the future.

This process of transforming the conceptual framework of history must follow the time-tested path of the sciences: making our assumptions explicit, making the principles by which we reason explicit, employing only evidence collected under controlled conditions, and so on. Another crucial element, less widely recognized, is that of formulating a conceptual framework that employs concepts of the proper degree of scientific abstraction, something I have previously discussed in Scientific Knowledge and Scientific Abtraction. This latter is perhaps the greatest hurdle for history, which has been understood as a concretely idiographic form of knowledge, in contradistinction to the nomothetic forms of knowledge of the natural sciences. [9]

In a future essay I will argue that history is intrinsically a big picture discipline, so that it must employ big picture concepts, which would make of history the antithesis of the idiographic. Moreover, there is no extant epistemology of big picture concepts (which we can also call overview concepts) that recognizes their distinctiveness and theoretically distinguishes them from smaller scale concepts, and this means that a transformation of history is predicated upon the formulation of an adequate epistemology that can clearly delineate a body of historical knowledge. In order to assess the hypotheses formulated above, it will be necessary to supply these missing elements of historical thought.

Notes

[1] I discussed Gilbert Murray on the failure of nerve in an earlier Centauri Dreams post, Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?

[2] The largest internal combustion engine is the Wärtsilä-Sulzer RTA96-C; one of the remarkable things about this engine is how closely it resembles the construction of an internal combustion engine you would find in any conventional automobile.

[3] The Tellus Institute describes eco-communalism as follows: “… the green vision of bio-regionalism, localism, face-to-face democracy, small technology, and economic autarky. The emergence of a patchwork of self-sustaining communities from our increasingly interdependent world, although a strong current in some environmental and anarchist subcultures seems implausible, except in recovery from collapse.”

[4] Darcy Ribeiro, The Civilizational Process, Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1968, p. 13.

[5] I have previously examined this idea in Trading Existential Opportunity for Existential Risk Mitigation: a Thought Experiment, where I posed the choice between the exploitation of nuclear technologies or the containment of nuclear technologies as a thought experiment.

[6] The newest reactor under development for the next class of US nuclear submarines, the S1B reactor, will be designed to operate for 40 years without refueling.

[7] Civilizations can and have changed their languages in order to secure greater efficiency in communication, and therefore idea diffusion. Mainland China has adopted a simplified character set. Both Japanese Kanji characters and traditional Korean characters were based on traditional Chinese models; the Japanese developed two alternative writing systems, Katakana and Hiragana (both of which are premodern in origin); the Koreans developed Hangul, credited to Sejong the Great in 1443. Under Atatürk, the Turks abandoned the Arabic script and adopted a Latin character set. Almost every civilization has adopted Hindu-Arabic numerals for mathematics.

[8] I have addressed this in answer to a question on Quora: If our civilization collapsed to pre-Industrial; do we have sufficient resources to recover (repeat the Industrial Revolution) to high tech? Or do we need to get into space on this go?

[9] On the distinction between the idiographic and the nomothetic cf. Windelband, Wilhelm, “Rectorial Address, Strasbourg, 1894,” History and Theory, Vol. 19, No. 2 (Feb., 1980), pp. 169-185.

I suppose (https://i4is.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Principium27-print-1911280846-comp.pdf, pp. 4-6), the power of heat engines – steam or internal combustion – in one form or another is possible on any planet where there is a free oxidizer in the atmosphere (it is assumed that intelligent beings capable of creating a technical civilization must be animals that can actively move, and they need an oxidizer). At the same time, it does not necessarily require fossil fuel reserves, but can develop as a related branch of agriculture and forestry. Including in this case, space rockets can be created on a particular chemical fuel.

And practical nuclear power is the result of a lucky combination of circumstances (or unfortunate, from the point of view of the inhabitants of post-war Japan), thanks to which fissile materials in the earth’s crust are available for industrial production. But it is not irreplaceable for space flights, because alternative technologies are also possible.

I also believe (https://i4is.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Principium19.pdf, pages 27-35, https://i4is.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Principium23.pdf, pp. 38-42), that most of the practical problems of space civilization, including the most ambitious (up to level IV on the extended Kardashev scale – the creation of many artificial universes and migration between them) can be solved by devices with external energy sources based on light sails.

Thanks for the links to your articles in Principium.

I agree that there are most likely alternative pathways to industrialization and to spacefaring technologies, and probably many more such pathways that we can imagine, given that our own civilization is our only data point on technological development. In the above I called the possibility of alternative pathways to technological development the “technological fungibility hypothesis.”

The difference between technological indispensability and technological fungibility is essentially the difference between a narrowly defined technological breakthrough and a class of related technologies. In the approach you outlined, there are a class of technologies by which a society can industrialize, and a class of technologies by which a civilization can achieve a spacefaring breakout. I am completely on board with this.

Best wishes,

Nick

And a small remark. Soviet Russia did not appear out of nowhere after the World War I. In the initial approximation, this event can be considered a Progressive reformation in the Orthodox world – similar to the Protestant reformation in the Catholic world. This reformation was much later and therefore more radical, which not only eliminated state and religious institutions that were inadequate for the modernist technical civilization of the World War I, but also replaced the anthropomorphic Creator of the Abrahamic religions with impersonal “objective laws of development”. But on a large scale of time, this civilization has largely preserved continuity. No complex civilizational formation appears “suddenly”, it is the result of the evolution of previous forms.

You know your Russian history far better than I. However, isn’t the wider context that there was a push for democracy in Europe that culminated in the failed revolutions of 1848. Yet, despite failure, democracy did gain political power over the ensuing decades. In Russia, the ascendency of Alexander III and after his assassination, by Nicholas II, both reactionary autocrats overturning the earlier democratization, who wanted to keep the ideas of European democracy at bay, ultimately resulted in the 1917 October Revolution that was as transformative of Russian society as the French Revolution of 1792 to French society, but longer-lived, (unless you consider Stalin as equivalent to Napoleon).

If so, then Soviet Russia is partially built on the changes in European society that came before it.

I recall a wonderful calculation which shows that even with direct-exhaust nuclear salt rockets, millions of tons could be lifted above Earth’s atmosphere before it becomes 10% more radioactive than present. With more advanced rockets, the numbers are in billions of tons even accounting for reasonable accident rates of mature technology. There also is a quasi-steady state, when further rise of radioactivity is balanced by decay of short- and medium-lived products, and the corresponding Earth-to-LEO traffic is orders of magnitude higher than current. Of course there is localized damage from accidents, but… with right mythology, it could be amortized to great extent.

We can lift every human into space by nuclear rockets without doing much damage to environment!

My assumption is that these numbers could be improved with mass adoption of the technology, which would mean the problem solving skills of a large number of individuals brought to bear on the difficulties that nuclear technologies involve. There is a sense in which this problem solving activity gives those who solves problems a purpose, and a sense of accomplishment when they do solve the problem. These are not insignificant factors.

Best wishes,

Nick

If a human weighs a tenth of a ton, boosting millions of tons to space would translate to tens of millions of humans, less if the intent is to offer life support or housing to the emigrants after their disposition.

If the system is 100% reliable with no failures, hiccups, misfires, or other fissile burps. Then there is the issue of managing the fissile material with the attendant security needs and police state development. While the emitted radiation levels average over the Earth may be low, one can be sure that the launch site and surrounding area will be unapproachable by humans.

In the real world, piss poor engineering, cost-cutting measures, unexpected conditions (e.g. the tsunami at Fukushima), black-market sales of nuclear material, and potentially terrorist use or sabotage, will make this approach far too risky to even contemplate execution. If you want such nuclear rockets, they should be confined to space and the surfaces of sterile worlds and moons.

Alex:

One thing that I find frustrating in these discussions is the huge gap between the energy density of chemical rocket fuel and the energy density of nuclear fissile material. What are your thoughts on the possibility that we might someday slightly bridge this gap by creating a better chemical fuel that has a higher energy density than the fuels that are currently in use for rocketry? Have you heard of “metallic hydrogen”? Metallic hydrogen is thought to occur naturally in the cores of some Jovian planets. Apparently, in the last few years there has been a trickle of reports from at least one scientific group stating that the elusive metallic hydrogen was finally created using a high pressure diamond anvil apparatus. Some calculations suggest that metallic hydrogen could be the “ultimate chemical fuel” leading to possibly an order of magnitude improvement in the velocity to which we could propel our space vehicles. There is something especially poetic about the idea of using a fuel that may be found at the core of Jupiter to open up the solar system! :-)

Some caveats are that the use of metallic hydrogen for fuel would depend on whether or not the material, once created using a high pressure apparatus, would remain stable at STP. In any case, what are your thoughts on the possibly of a revolutionary new chemical fuel, as the ‘chemical space’ of yet-to-be synthesized compounds is huge. Also, with machine learning and quantum computers on the horizon, might it still be plausible that we could pull a revolutionary rocket fuel out of the vast, unexplored chemical landscape!?

References

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-00149-7

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1742-6596/215/1/012194

I am not a rocket expert. I do know that there are chemical propellants that are more energetic than current ones, but they are extremely toxic as they are fluorine based. The increased Isp is hardly worth even thinking about.

Regarding metallic hydrogen. It would indeed be a wonder propellant. However, there are reasons to doubt it can remain stable at STP. That it must be created in a diamond anvil suggests that if it was stable, the pressures could be released and there would be a tiny speck of the material. That would be a major science story. This paper suggests that a metastable state cannot exist at STP. On the Lifetime of Metastable Metallic Hydrogen.

Fusion drives and even anti-matter seem more probable to me.

The most intriguing possibility that I am aware of is induced gamma emission from nuclear isomers. In theory, nuclei can store tremendous amounts of energy, and might be triggered to release it. In practice, it doesn’t seem to have reproduced well. See https://muonray.blogspot.com/2016/08/the-hafnium-isomeric-gamma-ray-weapon.html for an interesting blog on it. Note, of course, that since we’re talking about a tremendously powerful and highly concealable explosive, it is possible we’re not seeing all the results.

More fancifully, I daydream that “metatope power systems” might one day safely cascade gamma rays from common long-lived isotopes through a series of intermediates, so as to “make change” from radioactivity into a harmless and useful stream of electrical free energy.

The bound for specific impulse of chemical rockets is dictated by the nature of chemical bond. It’s energy, in general, cannot be higher than ionization potentials of component atoms, and it is divided by their mass. So, as you absolutely cannot get a compound with bonding energy of 10 eV per atom, and a powerful oxidizer which is lighter than oxygen, you cannot get a fuel pair with Isp much higher than current record of 550 s. Hydrogen is the exception, because it does not have a ballast of inert electrons and their corresponding nucleons. Conversion of metastable form of hydrogen can yield a very high Isp without any redox reactions. But the metastability rules apply to it, too. The more is the fraction of chemical bond energy you want to use, the less remains for kinetic barriers for decomposition of initial reagents, and the less stable they are. The article uses metallic-to-molecular transition energy release close or equal to that for recombination of atomic hydrogen, but in reality, it should be much lower for any chance of metastability to exist. (as a former chemist) I have the intuition than even 1000 s for metallic-hydrogen based propulsion is way too high. And making even a stabilized alloy in the required quantities would be next to impossible. Remember, you have to squeeze it in the DAC grain by grain to millions of bars! The catalytic route is also severely limited because the energies involved are very high, and will tend to destroy or transform any added compound.

Maybe in the entire phase-space of chemistry do exist some feasible routes to industrial quantities of metallic hydrogen-based compounds. For RTSC, it is worth to try, but for rockets it would be like trying to make conventional railways supersonic and use them for routine transportation. It could be more daunting task than building direct-exhaust thermonuclear rocket, but much less effective. Practicality and accessibility issues outweigh even the exponent in Tsiolkovsky equation. So I believe that CH4/O2 is the ultimate fuel pair of chemical rockets.

AND, if you did manage to produce some sort of stabilized metallic hydrogen, the first time a cosmic ray penetrated the tank, your rocket would blow up.

I think the search for higher ISP fuels for launching from Earth is kind of pointless, because we’re approaching the traffic level at which non-rocketry solutions, launch loops, rotovators, mass drivers, start to be cost effective.

Better propellants would be useful in space, though.

Of course, I wrote this bearing in mind that local effects and risks would be very high for current society. And maybe for many of the high-tech alternatives. But this is for us; less war-like species would find it more acceptable. Especially if they have (like Trisolarans :-) some form of transferring their identities from one body to another.

I forgot another thing, but here it comes again. The space exploration map varies widely with planetary home system architecture. While for us nuclear rockets may not be indispensable technology, for others they are. If we lived on a super-earth with escape velocity of 20 km/s and under ten times-thicker atmosphere (which is common across the galaxy), we would have no other choice. With a hot jovian in place of Mercury, we would got a mighty natural slingshot next to us (and a jewel of rarely imagined beauty in twilight skies), causing no one to seriously consider space sails and high-Isp rockets for centuries. And placing higher barrier for spacefaring-to-interstellar transition. On the other hand, exo-Martian dwellers in an orange dwarf system would not even care for nuclear rockets. Why launch them if folks can build SSTO in their garage? We may be lucky in some sense – if we become spacefaring, for us it will be not too far from becoming interstellar.

I find it difficult to disagree with anything in this remarkable essay, but

I must nevertheless interject a note of caution. I will limit my criticism to two items in particular.

1) To start with, I have my own unease with the Victorian Progress Myth. It not only promotes and enforces the new technologies made available in the late 18th century, it conveniently ignores or justifies the social conditions that made them possible, not to mention the ones it created. Mass industrialization required vast numbers of impoverished workers driven off the land in order to toil in the satanic urban mills. No matter how dismal the living conditions of the English peasant might have been, he did not willingly flock to London and Birmingham and trade them in for industrial servitude. He had no choice. The farm worker, the inheritor of an ancient, rich and stable agrarian culture with its own traditions, institutions and even rights; now found himself struggling to survive in a nightmare world over which he had no experience, little control and scarce benefit.

There were other problems, too. The Mercantilism and laissez-faire Capitalism of this new environment required not only cheap labor, but vast markets and limitless raw materials, too. And this led to colonialism, imperialism and war. Sure, the Romans had all that too, and they didn’t have steam, but they had slaves. Same difference.

Eventually, England, and the rest of Europe, paid a price for this Industrial Revolution: the Great War, a huge slaughter which, in retrospect, was fought for absolutely no good reason other than colonial rivalry. The economic devastation of this conflict led directly to cultural decline, Fascism and Communism, and an untouched New World superpower with a whole continent’s resources (including fossil fuels) to bring to the table. America may have greatly benefited from the Industrial Revolution, but it never paid the full price of admission.

2) We are, indeed, “space enthusiasts”, or we wouldn’t be sharing Centauri Dreams. We are impatient to go interstellar, or even interplanetary, and we are desperate to come up with simple reasons why we haven’t, or villains we can blame for not having done so. And to be honest, some of our reasons are purely emotional. But as in our politics, there are always demagogues ready to exploit those emotions for their own purposes.

If you really need a reason why space technology hasn’t fully caught on yet, maybe its precisely the Victorian constellation of Resources, Markets, Labor and Capital that needs to be blamed. There are no resources there so valuable that the energy costs of retrieving them isn’t prohibitive. There is no one there we can recruit as labor, or who will buy our produce, Therefore there is no return on investment to make it attractive to our financial and industrial power centers.

Our past successes in space were driven by military rivalry, national prestige and clever science lobbies who were able to disguise their projects in those terms. Even the money making space missions (earth resources, communications, navigation) had to be subsidized and kick started by taxpayer dollars.

Right now, unless some breakthrough technology can arise which will lower our space exploration costs by several orders of magnitude, its unlikely we will be able to justify too many more adventures in space, even purely scientific ones. In an age of declining wealth and rising costs, there will be two voices increasingly arguing against it., one on the Left, and one on the Right.

“There are too many problems down here for us to be wasting resources out there.”

“What’s in it for me?”

Agree with the eloquent, critical response. Am hopeful of a leap forward technology such as a space elevator or a discovery which prompts a space exploration mythology.

If a apace elevator would work, it would work better on Mars than on Earth. With effectively the same day length on both worlds, the distance from the surface to aero synchronous orbit is much shorter than to geosynchronous orbit, and Mars surface gravity is only about .34 Earths surface gravity, so the required strength of the tether would be much less.

However, when folks talk of the required tether strength they usually only consider the strength for the tether to support itself, and the weight of the elevator car. Unfortunately, the physics requires the tether to provide the lateral force to accelerate the horizontal speed of the elevator car from the speed with which the surface of the Earth rotates ( about 1,000 MPH) to the speed with which a satellite in geosynchronous orbits, which is about 5 times as fast. Worse, the vector of the lateral force the tether would have to apply to the elevator car would result in much much much higher forces it the tether.

I suppose that if the lateral force was supplied by a reaction drive (chemical rocket, or at best once in vacuum perhaps an ion drive supplied with electrical power by conductors in the tether) then it might work, with the tether only supporting the vertical weight of the elevator car.

And think of the environmental impact statement and public hearings required to construct such a thing on Earth! Not to mention the liability insurance!

Perhaps someone will come along with an idea such as light-pumping metamaterials for space travel.

Someone has. That is physicist Jack Sarfatti. He theorizes that meta materials can be used to realize low energy Alcubierre Warp drive technology for hyper fast but still sub-light speeds at very low cost in energy and of course, no ejection of matter.

If I am not mistaken, he proposes trapping light, not pumping it.

He calls it a Frohlich pump but what’s important is he thinks the physics of a low energy warp drive can actually be realized at low energy in certain metamaterials. He says real world data from Military encounters with ‘Tic-Tac’s’ prove it.

Scholarship suggests this is not the case [1]. It was the unskilled poor poor who most benefitted from the industrial revolution through rising wages. Yes industrial slums and factories were appalling places to live and work to our modern eyes, but we tend to have a far too rosy view of country life of peasants. People moved to the cities because there was a benefit to be had in the lives of the workers.

I have little doubt that in a another century people will think our lives were terrible compared to theirs, yet somehow we largely seem to accept our conditions. Some people would even like to make those conditions harsher again.

1. “A Farewell to Alms: A Brief Economic History of the World” G. Clark (2007) (See especially ch 14: Social Consequences)

I’d be careful about citing “A Farewell to Alms” as a source. Even the title hints strongly it has an ideological axe to grind. Perhaps a bit too Ayn Randish for my squishy Liberal sensibilities…

To be fair, I didn’t read Clark, (its available online as a pdf) but I did read several scholarly reviews of it and the book appears, to say the least, controversial. I found his idea of prosperity, work ethic and middle class values propagating through a population genetically (yes, in a biological, Darwinian fashion!) particularly disturbing. Survival of the richest? It all sounds vaguely fascist to me. “Yes dear, those people are just different from us. They were born that way. Its in their blood.”

But then again, to be fair, perhaps I (and his critics) misunderstood his thesis. Its why I’ve always preferred the physical sciences to the social ones. Its too easy for an articulate speaker to be mistaken for a perceptive one.

At any rate, those who are interested can Google the man, his books and his critics. They can decide for themselves.

Fair point about his views. The book was recommended many years ago by the heterodox economist Prof. Bradford DeLong.

However, we have a contemporary version with the rapid industrialization of China. AFAIK, peasants in the country are not leading comfortable but poor lives, and the exodus from the land to the industrial cities is willing, even if work conditions can be so poor that companies like FoxConn have to prevent suicides, and other companies treat their workers like indentured slaves. We know wages in China are rapidly increasing and domestic consumption increasing, which is an analogous situation to the British industrial revolution.

The social sciences are not physics, all research and analysis in those fields is highly subjective. You can prety much find whatever facts you need to prove whatever you want. And no, I’m not being critical, its just the nature of the field. Still, the opinions of an informed and intelligent man are always of value, even if they can’t be formally proven or disproven, or even if they contradict themselves or can be shown to be biased. The interpretations of someone you disagree with totally can still be of great value.