I’m startled by the findings in a new paper from Dominique Segura-Cox (Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics), who argues that based on the evidence of one infant system, we may have planet formation all wrong, at least in terms of when it occurs. The natural assumption is that the star appears first, the planets then accruing mass from within the circumstellar disk. But Segura-Cox and team have found a system in which planet and star seem to be forming all but simultaneously. IRS 63 is a protostar about 470 light years out that is less than half a million years old. Swathed in gas and dust, the star is still gathering mass, but evidence from the disk suggests that the planets have already begun to form.

One reason for the surprise factor here is that we’ve looked at many young stellar systems and their disks, most of them at least one million years old, and the assumption has been that the stars were well along in their own formation process before the planets began to build. Ian Stephens (Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian), a co-author on this paper, is quite clear on the matter: “Traditionally it was thought that a star does most of its formation before the planets form, but our observations showed that they form simultaneously.”

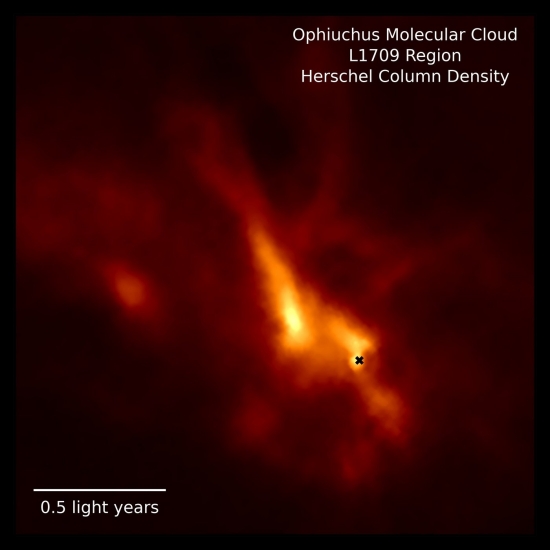

Image: The dense L1709 region of the Ophiuchus Molecular Cloud, mapped by the Herschel Space Telescope, which surrounds and feeds material to the much smaller IRS 63 proto-star and planet-forming disk (location marked by the black cross). Credit: MPE/D. Segura-Cox; Herschel data from ESA/Herschel/SPIRE/PACS/D. Arzoumanian.

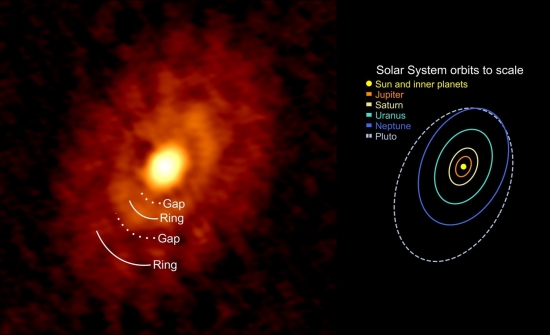

Planets and host star as siblings? It takes a bit of getting used to, but the Segura-Cox team is finding gaps and rings, the rings accumulating dust suitable for planet formation, within the IRS 63 disk. The paper summarizes earlier disk observations at other stars, where the gaps and rings found in the disks have generally appeared in so-called Class II disks with ages of one million years or more — ALMA (Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array) has turned up more than 35 of these — with gaps showing little or no dust emission, a fact usually explained by a planet-mass object shaping the dust into rings.

Fitting IRS 63 into this picture, we get this:

These results indicate that planet formation must be both efficient and well underway by the class II phase. Recent dust mass measurements of class II disks also indicate that observed dust depletion could be explained if substantial mass is locked into planetesimals on timescales less than 0.1-1 Myr, placing early planet formation into the younger class I phase and possibly even earlier. In comparison to the rings and gaps found in the older disks of class II objects, the annular substructures in the younger disk of IRS 63 have dust emission even in the G1 and G2 gaps and are wider and have lower contrast. In IRS 63, it is unclear whether or not sizeable planetary-mass bodies are creating these gaps.

Stephens estimates that planets start to form as early as the first 150,000 years of a system’s formation, at the earliest stages of star growth. If each of the gaps at IRS 63 is opened by a single planet, the authors estimate the first gap (G1) would require a planet of 0.47 Jupiter mass, while the second gap (G2) demands 0.31 Jupiter mass, both numbers being upper limits.

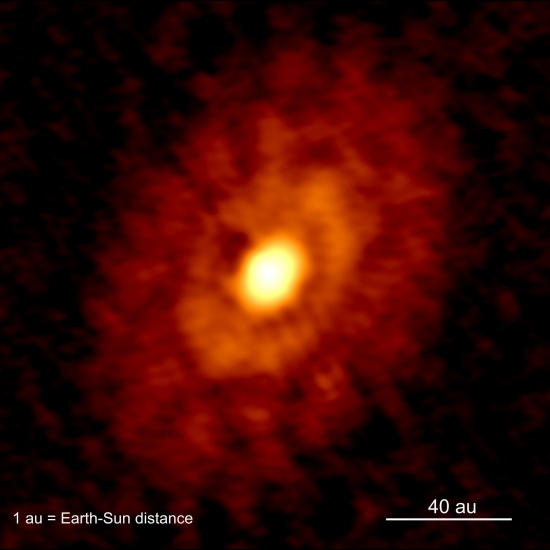

Image: The ALMA image of the young planet-forming dust rings surrounding the IRS 63 proto-star, which is less than 500,000 years old. Credit: MPE/D. Segura-Cox.

The paper notes that Jupiter is an interesting world in this kind of scenario. The disk at IRS 63 is similar in size to our own Solar System, and the mass of the proto-star not far off that of the Sun. Such early formation implies a distant new planet migrating into its present position:

For a planetary embryo made of solids to trigger runaway accretion of gaseous material—required in the core-accretion model of gas-giant planet formation—the critical mass of 10MEarth must be met by the solid core. This condition is readily met in the young IRS 63 disk, even for a somewhat low efficiency (<10%) of core formation out of the available dust grains. The large dust mass in the outer dust disk—combined with the 27 and 51 au radii of the rings of IRS 63—is consistent with evidence that Jupiter’s core could have formed beyond 30 au in our own Solar System and later migrated inward. Giant-planet cores may often form in the exterior regions of large disks starting from the early phases of star formation.

Image: The rings and gaps in the IRS 63 dust disk compared to a sketch of orbits in our own Solar System at the same scale and orientation of the IRS 63 disk. The locations of the rings are similar to the locations of objects in our Solar System, with the inner ring about the size of the Neptune orbit and the outer ring a little larger than the Pluto orbit. Credit: MPE/D. Segura-Cox.

At IRS 63, the researchers find that about 0.5 Jupiter masses of dust are available at distances beyond 20 AU, along with unspecified amounts of gas. Planet formation at large distances from the star might involve solid material totalling at least 0.03 Jupiter masses, forming the kind of planetary core that can accrete gas and swell into a gas giant planet.

The paper is Segura-Cox, et al., “Four annular structures in a protostellar disk less than 500,000 years old,” Nature Vol. 586 (7 October 2020), pp. 228-231 (abstract).

I like the idea that gas giants and rocky planets form at the same time of the star. An unstable gas cloud could collapse and make a 10 earth mas gas giant? The idea of the how and why the gas giant has to migrate is not explained. I am not saying they don’t migrate, but then would all of our gas giants would have to migrate? I thought that the protoplanetary disk is formed because the centrifugal force keeps the dust from moving to far inwards towards the Star so it is easier for the round, protoplanetary dust cloud to collapse vertically, but not horizontally. Kippenhahn 1983. As a result, a protoplanetary disk forms. This theory is called the Nebular hypothesis which was developed by Imanuel Kant. Also there idea that the planets grab all or most of the angular moment from the star. Ibid., 100 Billion Suns.

Another very interesting paper just out with regard to planetary systems formation and modelling:

https://www.mpg.de/15433934/earth-like-planets-often-come-with-a-bodyguard

The original paper: Schlecker et al.: “The New Generation Planetary Population Synthesis (NGPPS). III. Warm super-Earths and cold Jupiters: A weak occurrence correlation, but with a strong architecture-composition link”

https://www.aanda.org/component/article?access=doi&doi=10.1051/0004-6361/202038554

Not entirely new, I think, but a confirmation of previous research:

– High metallicity resulting in large mass protoplanetary disk leads to formation of giant planets in wide orbits.

– This in turn leads to terrestrial type planets in the inner system.

– And a lot more fascinating stuff…

Definitely worthy of a post!

Good grief, Ronald, you’re anticipating me. I just finished the piece on this paper that will run tomorrow morning when I saw your comment!

I could have known, I should have known and I knew it!

Looking forward to it, and with proper admiration for you: the paper is sizable and reasonably tough, that is to say, there is a lot of information in it.

Success!

But why does the outer ring appear to be split into equally spaced concentrations? Not easy to count as some bits are really hazy, but there appear to be about 20 of these. 20 proto-planets in the outer ring? Or is this an artifact of the observing system?

At a completely different scale, but perhaps of interest, when I heat the oil in my (stainless steel) frying pan to fry an egg, as it reaches frying temperature, the oil at the rim of the pan shows up regularly spaced (about 5 mm apart) light and dark spokes. It sounds ridiculous, but could there be some common factor involved in both cases?

It seems only within the last day or so I was looking at a Hertzsprung Russell diagram which denoted the tracks of varied mass proto-stars headed for the main sequence – and it indicated that the more massive a star the more quickly it arrived at a state of hydrogen ignition. Stars considerably more massive than the sun could make this dash in HZ space in tens or hundreds of thousands of years and red dwarfs could take tens or a hundred million years. Now if I could just find the diagram, I could be a little more quantitative. But in the case under consideration, I did not see an estimate of the proto-star mass. If the proto-star mass is substantially below solar, then the picture drawn might not contradict the picture focused on solar mass cases; just distinguish itself from it.

A little more quantitative on that proto-star trek to the main sequence.

Solar Time in

Mass Years

15 60,000

9 150,000

3 3,000,000

1 50,000,000

0.5 150,000,000

From circumstellar disk discussions that did not address stellar mass directly, I had been led to believe that planet formation occurred within a time-frame of ten million years or less. But judging from the range of main sequence stars that possess them and the rate at which proto-stars migrate to MS status… Is it just a question of which comes first: stellar ignition or proto-planet?