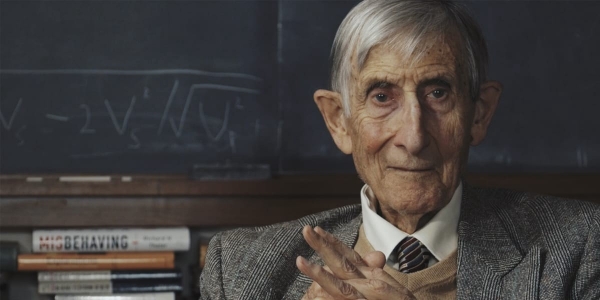

Anyone who ever had the pleasure of talking to Freeman Dyson knows that he was a gracious man deeply committed to helping others. My own all too few exchanges with him were on the phone or via email, but he always gave of his time no matter how busy his schedule. In the article below, Colin Warn offers an example, one I asked him for permission to publish so as to preserve these Dysonian nuggets for a wider audience. Colin is an Associate Propulsion Component Engineer at Maxar, with a Bachelor of Science in mechanical engineering from Washington State University. His research interests dip into in everything from electric spacecraft propulsion to small satellite development, machine learning and machine vision applications for microrobotics. Thus far in his young career, he has published two papers on the topics of nuclear gas core rockets and interstellar braking mechanisms in the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. He tells me that when he’s not working on interstellar research, he can be found teaching music production classes or practicing martial arts.

by Colin Warn

Three years ago, I decided to make a switch from being a part time dance music ghost producer to study something that would help advance humanity’s knowledge of the stars. Eventually, I decided that something would be mechanical engineering, a switch which was in no small part due to space podcasts that introduced me to cool technologies such as Nuclear Pulsed Propulsion (NPP): Rockets propelled by small mini-nuclear explosions. The man behind this technology? Freeman Dyson.

Dyson worked on Project Orion for four years, deeply involved in studies that produced the world’s first and only prototype spacecraft powered by NPP. Due to the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty, which he supported, humanity’s best bet for interstellar travel was filed away. Yet, something about the audacity of this project resonated with me decades later when I uncovered it, especially when I found out that Dyson was in charge of this project despite not being a PhD.

So, as a bright-eyed and optimistic freshman entering his first year of college, figuring that out of anyone in the world he would have the best insights on what technology would lead humanity to the stars, I decided to send him this email:

Hello Professor Dyson,

My name is Colin Warn, and I’m a freshman pursuing a degree in mechanical engineering/physics.

Had a few questions for you regarding how I should structure my career path. My ambitions are to work on interstellar propulsion technologies, and I figured you might know a thing or two about the skill set required.

If you have the time, here’s what I’d love to hear your opinion on:

1. What research/internships would you suggest I focus on as an undergraduate to learn the skills that will be needed for working on advanced propulsion technologies? Especially in my freshman and sophomore years?

2. For my initial undergrad years, would you suggest that I focus more on taking physics or engineering courses initially?

Thank you so much in advance for your time. Been reading the book your son wrote about Orion. Let’s just say the reactions I’ve been getting from my friends when I tell them what I’m reading about is already quite fun to observe.

Regards,

-Colin

I sent it to his Princeton email, as I’ve sent many emails in the past to fairly high-caliber people, without a hope of getting anything in return.

Two days later, I woke up to find this email in my inbox.

Dear Colin Warn,

I will try to answer your two questions and then go on to more general remarks.

1. So far as I know, the only techniques for interstellar propulsion that are likely to be cost-effective are laser-propelled sails and microwave-propelled sails. Yuri Milner has put some real money into his Starshot project using a high-powered laser beam. Bob Forward many years ago proposed the Starwisp spacecraft using a microwave beam. Either way, the power of the beam has to be tens of Megawatts for a miniature instrument payload of the order of a gram, or tens of Terawatts for a human payload of the order of a ton. My conclusion, the manned mission is not feasible for the next century, the instrument mission might be feasible.

For the instrument mission, the propulsion system is the easy part, and the miniaturization of the payload is the difficult part. Therefore, you should aim to join a group working on miniaturization of instruments, optical sensors, transmitters and receivers, navigation and information handling systems. These are all the technologies that were developed to make cell-phones and surveillance drones. An interstellar mission is basically a glorified surveillance drone. You should go where the action is in the development of micro-drones. I do not know where that is. Probably a commercial business attached to a technical university.

2. For undergraduate courses, I would prefer engineering to physics. Some general background in physics is necessary, but specialized physics courses are not. More important is computer science, applied mathematics, electrical engineering and optics, chemistry of optical and electronic materials, microchip engineering. I would add some courses in molecular biology and neurology, with the possibility in mind that these sciences may be the basis for big future advances in miniaturization. We still have a lot to learn by studying how Nature does miniaturization in living cells and brains.

This email contained more detailed insights to my questions than I could have ever hoped for. Then to top it all off, he still had one more piece of advice for me to a question I hadn’t even asked.

General remarks. In my own career I never made long-range plans. I would advise you not to stick to plans. Always be prepared to grab at unexpected opportunities as they arise.Be prepared to switch fields whenever you have the chance to work with somebody who is doing exciting stuff. My daughter Esther, who is a successful venture capitalist running her own business, puts at the bottom of every E-mail her motto, “Always make new mistakes”. That is a good rule if you want to have an interesting life.

With all good wishes for you and your career, yours sincerely,

Freeman Dyson.

Upon reading this email in 2018, I promised myself that one day I’d put myself in a position to thank him in person. Sadly I’ll never get the opportunity. I discovered watching an old YouTube video featuring him that he died in February of 2020.

So this article is my way of saying thank you to him. For creating literal star-shot projects to inspire a new generation. For being someone who always questioned the status quo. But most of all, for still being down to earth enough to email some amazingly insightful answers to a freshman’s cold-email. I hope one day I’m in a position where I can pass on the favor.

For an overview of his life and achievements:

Freeman Dyson

For almost every one of us, achieving even a tiny fraction of what he achieved would be judged a major success.

Dyson has often poked at the consensus with a contrarian viewpoint. Sometimes those contrarian ideas offered interesting avenues to pursue. My home library has a number of his books, each a delight to read, and often containing very interesting ideas that seem worth pursuing.

My sense is that Dyson remained intellectually sharp in his old age, and did not succumb to the mental decline often associated with age. Is there anyone in the younger generations who is his equal?

By the time I was old enough to think seriously about it, I did not think about it. Like a duckling follows a duck into water, I went into medicine. And came out – retired. Without any regrets. Not as quickly as some others I knew of – such as a hand surgeon who retired after 12 years of practice, but retired nevertheless.

Wonderful tribute. When I was in residence at the IAS in 1991 for about 9 months (working on Henry Norris Russell bio) he was one of the most supportive and friendly members, stimulating me to think in more creative ways.

Your reminiscences of Dyson at IAS would make a wonderful article here, David, if you’re ever so inclined. You have seen him in ways that none of us have. Thanks for your comment.

David’s biography of Henry Norris Russell can be found here:

https://www.amazon.com/Henry-Norris-Russell-David-DeVorkin/dp/0691049181/ref=sr_1_16?crid=ZFGK6U3URVSQ&keywords=david+devorkin&qid=1644452107&s=books&sprefix=david+devorkin%2Cstripbooks%2C48&sr=1-16

Freeman Dyson had a twenty three year correspondence with a Science and Technology class at small college in Oklahoma and was published as

“Dear Professor Dyson

Twenty Years of Correspondence Between Freeman Dyson and Undergraduate Students on Science, Technology, Society and Life”

by Dwight E. Neuenschwander

He answers questions the students have on a wide variety of topics as well as relevant excerpts from his books. Well worth a read.

Thanks, David. I had no idea this existed!

Enjoyed this engaging and hopeful recount of an email. Note the absence of equivocation in his communication. That is how credibility is read and spoken.

I met Mr. Dyson 3 times and spoke with him on the phone once, for a total of about 90 minutes of interaction.

He was the most polite, congenial, informative, and thoughtful person I have encountered. Not to mention brilliant beyond words.

Humanity needs more Freeman Dysons. I am afraid that we will not see his like again. At least, not soon.

I share your thought on that, James. How often can such a man come along?

That’s a very nice story. I was an IAS fellow for 3 years, in residence for 2+ preparing for HST GTO programs as NASA recovered from Challenger. I usually lunched in the excellent cafeteria except Tuesday lunch in the adjacent meeting room, and Freeman would always scan the room then more often than not come over to our table of stellar dynamicists and observational astronomers. “I like astronomers more than particle physicists” he once said. I recall conversations about how his most frustrating time was serving on the Space Science Board vs intrigue on JASON, steam powered rockets laser launched to orbit, novel modes of telescopic adaptive optics, and regret that Orion didn’t progress a bit farther because of the test ban. He always asked what we were working on in a supportive way. He and Martin Schwarzschild were the friendly, approachable, and informative greats there then.

Wonderful to hear this, Gerald. Thanks! I recall Dyson’s interest in laser-launch to orbit; he kept coming back to it in an interview I did with him for my Centauri Dreams book. Loved the quote about liking astronomers more than particle physicists…

I developed my love for astronomy after college (read Centauri Dreams). Didn’t quite manage to convert it into a career, yet. But am hoping my kids may find the field interesting enough to go in that direction and a guidance like this will definitely help. I tell people that everything we are doing is in this world is progress towards the ultimate goal of Interstellar travel and colonization.

Welcome to the interstellar community! Glad to have you on Centauri Dreams.

The problem with all the alternative propulsion systems like solar wind sails is time. Acceleration is so slow that while it may continue for a very long time, and eventually get the spacecraft up to some sort of a reasonable speed, time is not what humans have a lot of.

40psol (percent of the speed of light) would enable humans to transit to another star system and colonize it, within an acceptable portion of a human lifetime. To get up to this speed mustn’t take forever, or the type of colonist you want to be aboard would reject the trip out of hand. Life is meant to be lived, not imprisoned in a capsule with limited lifestyle choices floating through the void.