The continuing release of papers related to or referring to the Breakthrough Starshot sail concept is good news for the entire field. Interstellar studies as an academic discipline has never had this long or sustained a period of activity, and the growing number of speakers at space-related conferences attests to the current vitality of starflight among professionals and the general public alike.

Not all interstellar propulsion concepts involve laser-beaming, of course, and we’ll soon look at what some would consider an ever more exotic concept. But today I’m focusing on a paper from Ho-Ting Tung and Artur Davoyan, both in the Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Department at UCLA. You could say that these two researchers are filling in some much needed space between the full-bore interstellar effort of Breakthrough Starshot, the Solar System-oriented laser work of Andrew Higgins’ team at McGill, and much smaller, near-term experiments we could run not so far from now.

Of the many potential show-stoppers faced by a mission to another star at our stage of development is the need to develop the colossal laser array envisioned by Starshot. The Higgins array is at a smaller scale, as befits a concept with nearby targets like Mars. What Tung and Davoyan envision are tiny payloads (here they parallel Breakthrough), some no more than a gram in mass, but the authors push the sail with a 100 kW array about a meter in size. Compare this with Breakthrough’s need for a gigantic square-kilometer array of 10 kW lasers with a combined output of up to 100 GW.

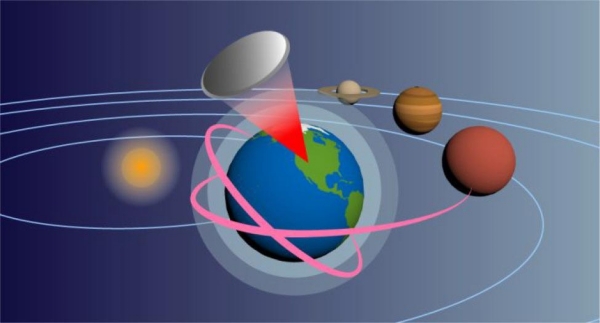

Image: In this illustration, a low-power laser (red cone) on Earth could be used to shift the orbit (red lines) of a small probe (grey circle), or propel it at rapid speeds to Neptune and beyond. Credit: Ho-Ting Tung et al.

The UCLA work takes us to a consideration of operations with spacecraft in Earth orbit as well as payloads sent on interplanetary trajectories. Thus we are in the realm of the kind of missions that today would demand chemical or electric propulsion, and we are looking at a system that might be used, for example, for orbital adjustment of Earth satellites after launch, or in the case of chip-class payloads, interplanetary missions with surprising velocities, up to 5 times that of New Horizons. As noted, the needed laser aperture is, by the standards of the missions we’ve discussed earlier, small:

…a sail with w = 1 m would require a laser with an aperture D ? 26 m (compare with the 30 m diameter primary mirror of the Thirty Meter Telescope under construction). However, we stress that most practical scenarios are limited to low and medium Earth orbits that require a much shorter operation range (z ? 1000km), and therefore a significantly smaller laser array.

Indeed, an array a meter in size could be efficient, maneuvering small satellites in Earth orbit, or being used to bring small chip-craft up to Solar System escape velocity. Thus we have the potential to create laser propulsion experiments and missions with array powers of ? 100 kW and array sizes that do not require kilometers of desert for their construction. Payloads can range from 1 to 100 grams depending on the mission, though the focus here is wafer-scale, on the order of 10 centimeters.

As to sail materials, the authors calculate that for maximum reflectivity coupled with rapid cooling, silicon nitride and boron nitride are the materials of choice:

Broadband spectral emissivity of silicon nitride…results in a better heat rejection (i.e., lower temperature) as compared [to] narrow band BN thermal emitters. However, boron nitride being lighter than silicon nitride allows design of very light-weight light-sails, which eventually translates onto higher velocity gain, ?v.

The paper offers possible ways to create these structures, including using metamaterials formed into nanostructured architectures with nanometer-scale ‘sandwich’ panels between material layers, or using ‘micro pillars’ within the photonic structure.

The broader picture is that we’re mapping out how to experiment with lasers and materials that may begin moving up the ladder of mission complexity. There are innumerable issues to be overcome, but the early theoretical work is crucial to making what may become an interplanetary infrastructure a reality. These examinations should also feed into the ambitious work on projects that aim at interstellar missions.

The paper is Ho-Ting Tung et al, Low-Power Laser Sailing for Fast-Transit Space Flight, Nano Letter,” Nano Letters 22, 3 (31 January 2022), 1108–1114 (abstract).

Now that the idea of small, very fast, probes (chipsats) is becoming more mainstream, we should have scientists and engineers determining how to use them efficiently to do science. Their small size implies that the optics will be limited, for example using smartphone-size cameras. Other instruments will have to be miniaturized to be useful. What instruments are possible? Orbital observations can be simulated by having a stream of chipsats doing flybys. How will that work and what is needed to ensure the data can be pieced together and returned to Earth? Do the chipsats have to communicate and coordinate between themselves, a feature that is being done with drone swarms. Will they need new error-correcting protocols and smart coordination software to allow for individual chipsat failures? Can chipsats or larger versions be used to decelerate the following chipsat, rather like the Bob Forward approach for decelerating a huge interstellar laser sail ship? With deceleration, the range of mission types increases.

Someone must be thinking about these opportunities and issues, but so far we seem to be in a situation analogous to the invention of heavier than air flight, and rocket propulsion. New toys but with their potential hardly considered. Visionaries like Clarke saw the potential of spaceflight and could engagingly explain the benefits – starting with enabling his geosynchronous comsats and what that would imply. Is there anyone doing the same with beamed sails and chipsats to show why we should develop them and what the benefits would be when used effectively, possibly in out-of-the-box ways?

Even this is too ambitious a beginning. There is a lot to learn, and it can be done with existing technology.

Send an experimental packet to the ISS that contains several “satellites” and a small laser. The laser need only be a few watts, affixed to the exterior of the station and powered by the onboard electrical system. The satellites can be aerogel (or similar) spheres with embedded miniature batter, accelerometer , gyroscope and a milliwatt transmitter to broadcast telemetry from these few instruments.

Cast the satellites out the airlock, with a gentle push in a suitable direction. Calibrate for motion and attitude effects due to atmospheric drag and solar radiation, then illuminate them with the laser for the duration of the experiment. The laser aperture may need to be initially broadened to fully illuminate the sphere since the distances will not be large.

The expected effects are easy to calculate so they are not important. What is important is whether the laser can track the satellites, the ability to send and receive telemetry, and alter the laser direction and focus in response, measure the acceleration and torque due to even and uneven illumination, and doing so while the distance continues to increase.

Simple and not very expensive, but still challenging and the experiment would provide valuable data and experience for more ambitious next steps.

We have of course experimented with larger light sails, however solar illumination is planar and extremely broad. Artificial illumination is very different and far more difficult to engineer and exploit, and we can make a start, small though it may be.

A most excellent proposal, Ron S!

Outside of the box thinking, wonderful.

Intensify the laser, see how much the craft can take.

Now, phys.org had recent articles on light interacting with magnetic fields. The was a Sci Am article a decade or two back talking about lasers inducing a much more powerful lightning stroke. Might a chipsail ride a blue jet or sprite starwisp style? The laser is just there to get the power flowing…like siphoning off gasoline with a hose.

‘Artificial illumination is very different and far more difficult to engineer and exploit, and we can make a start, small though it may be.’

There is a lot of money invested in this area and therefore a lot of information available or trade secrets.