Ongoing projects like JHU/APL’s Interstellar Probe pose the question of just how we define an ‘interstellar’ journey. Does reaching the local interstellar medium outside the heliosphere qualify? JPL thinks so, which is why when you check on the latest news from the Voyagers, you see references to the Voyager Interstellar Mission. Andreas Hein and team, however, think there is a lot more to be said about targets between here and the nearest star. With the assistance of colleagues Manasvi Lingam and Marshall Eubanks, Andreas lays out targets as exotic as ‘rogue planets’ and brown dwarfs and ponders the implications for mission design. The author is Executive Director and Director Technical Programs of the UK-based not-for-profit Initiative for Interstellar Studies (i4is), where he is coordinating and contributing to research on diverse topics such as missions to interstellar objects, laser sail probes, self-replicating spacecraft, and world ships. He is also an associate professor of space systems engineering at the University of Luxembourg’s Interdisciplinary Center for Security, Reliability, and Trust (SnT). Dr. Hein obtained his Bachelor’s and Master’s degree in aerospace engineering from the Technical University of Munich and conducted his PhD research on space systems engineering there and at MIT. He has published over 70 articles in peer-reviewed international journals and conferences. For his research, Andreas has received the Exemplary Systems Engineering Doctoral Dissertation Award and the Willy Messerschmitt Award.

by Andreas Hein

If you think about our galaxy as a vast ocean, then the stars are like islands in that ocean, with vast distances between them. We think of these islands as oases where the interesting stuff happens. Planets form, liquid water accumulates, and life might have emerged in these oases. Until now, interstellar travel has been primarily thought in terms of dealing with how we can cross the distances between these islands and visit them . This is epitomized by studies such as Project Daedalus and most recently Breakthrough Starshot, Project Daedalus aiming at reaching Barnard’s star and Breakthrough Starshot at Proxima Centauri. But what if this thinking about interstellar travel has missed a crucial target until now? In this article, we will show that there are amazing things hidden in the ocean itself – the space between the stars.

It is frequently believed that the space between the stars is empty, although this stance is incorrect in several ways, as we shall elucidate. The interstellar community is firmly grounded in this belief. It is predominantly focused on missions to other star systems and if we talk about precursors such as the Interstellar Probe, it is about the exploration of the interstellar medium (ISM), the incredibly thin gas long known to fill the spaces between the stars, and also features of the interaction between the ISM and our solar wind, such as the heliosheath, or with its interaction with microscopic physical objects or phenomena linked to our solar system. However, no larger objects between the stars are taken into account.

Image: Imaginary scenario of an advanced SunDiver-type solar sail flying past a gas-giant nomadic world which was discovered at a surprisingly close distance of 1000 astronomical units in 2030 by the LSST. The subsequently launched SunDiver probes spotted several potentially life-bearing moons orbiting it. (Nomadic world image: European Southern Observatory; SunDivers: Xplore Inc.; Composition: Andreas Hein).

Today, we know that the space between the stars is not empty but is populated by a plethora of objects. It is full of larger flotsam and smaller “driftwood” of various types and different sizes, ejected by the myriads of islands or possibly formed independently of them. Each of them might hold clues to what its island of origin looks like, its composition, formation, and structure. As driftwood, it might carry additional material. Organic molecules, biosignatures, etc. might provide us with insights into the prevalence of the building blocks of life, and life itself. Most excitingly, some important discoveries have been made within the last decade which show the possibilities that could be obtained by their exploration

In our recent paper (Lingam, M., Hein, A.M., Eubanks, M. “Chasing Nomadic Worlds: A New Class of Deep Space Missions”), we develop a heuristic for estimating how many of those objects exist between the stars and, in addition, we explore which of these objects we could reach. What unfolds is a fascinating landscape of objects – driftwood and flotsom – which reside inside the darkness between the stars and how we could shed light on them. We thereby introduce a new class of deep space missions.

Let’s start with the smallest compound objects between the stars (individual molecules would be the smallest objects). Instead of driftwood, it would be better to talk about sawdust. Meet interstellar dust. Interstellar dust is tiny, around one micrometer in diameter, and the Stardust probe has recently collected a few grains of it (Wetphal et al., 2014). It turns out that it is fairly challenging to distinguish between interstellar dust and interplanetary dust but we have now captured such dust grains in space for the first time and returned them to Earth.

The existence of interstellar dust is well-known, however, the existence of larger objects has only been hypothesized for a long time. The arrival of 1I/’Oumuamua in 2017 in our solar system changed that; 1I is the first known piece of driftwood cast up on the beaches of our solar system. We now know that these larger objects, some of them stranger than anything we have seen, are roaming interstellar space. There is still an ongoing debate on the nature of 1I/’Oumuamua (Bannister et al., 2019; Jewitt & Seligman, 2022). While ‘Oumuamua was likely a few hundred meters in size (about the size of a skyscraper), larger objects also exist. 2I/Borisov, the second known piece of interstellar driftwood, was larger, almost a kilometer in size. In contrast to ‘Oumuamua, it showed similarities to Oort Cloud objects (de León et al., 2019). The Project Lyra team we are part of has authored numerous papers on how we can reach such interstellar objects, even on their way out of the solar system, for example, in Hein et al. (2022).

Now comes the big driftwood – the interstellar flotsam. Think of the massive rafts of tree trunks and debris that float away from some rivers during floods. We know from gravitational lensing studies that there are gas planet-sized objects flying on their lonely trajectories through the void. Such planets, unbound to a host star, are called rogue planets, free-floating planets, nomads, unbound, or wandering planets. They have been discovered using a technique called gravitational microlensing. Planets have enough gravity to “bend” the light coming from stars in the background, focusing the light, brightening the background star, and enabling the detection even of unbound planets.

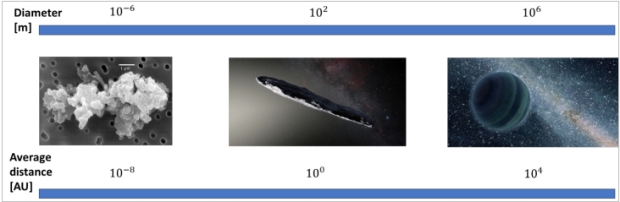

Until now, about two hundred of these planets (we will call them nomadic worlds in the following) have been discovered through microlensing. These detections favor the more massive bodies, and so far objects with a large mass (Jupiter-sized down to a few Earth masses) have been detected. Although our observational techniques do not yet allow us to discover smaller nomadic worlds (the smallest ones we have discovered are a few times heavier than the Earth), it is highly likely that smaller objects, say between the size of the Earth and Borisov, exist. Fig. 1 provides an overview of these different objects and how their radius is correlated with the average distance between them according to our order of magnitude estimates. Note that microlensing is good at detecting planets at large interstellar distances, even ones thousands of light years away, but it is very inefficient (millions of stars are observed repeatedly to find one microlensing event), and with current technology is not likely to detect the relative handful of objects closest to the Sun.

Fig. 1: Order of magnitude estimates for the radius and average distance of objects in interstellar space

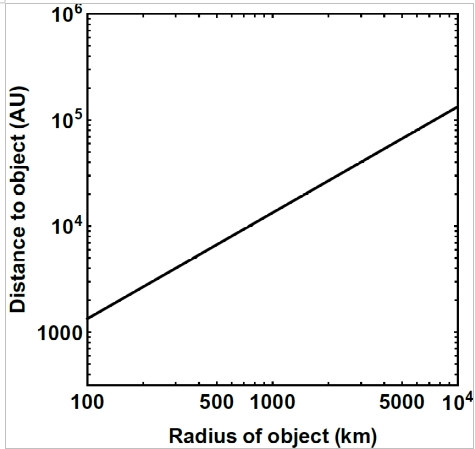

We have already explored how to reach interstellar objects (similar to 1I and 2I) via Project Lyra. What we wanted to find out in our most recent work is whether we can launch a spacecraft towards a nomadic world using existing or near-term technology and reach it within a few decades or less. In particular, we wanted to find out whether we could reach nomadic worlds that are potentially life-bearing. Some authors have posited that nomadic worlds larger than 100 km in radius may host subsurface oceans with liquid water (Abramov & Mojzsis, 2011), and larger nomadic planets certainly should be able to do this. Now, although small nomadic worlds have not yet been detected, we can estimate how far such a 100 km-size object is from the solar system on average. We do so by interpolating the average distance of various objects in interstellar space, ranging from exoplanets to interstellar objects and interstellar dust. The size of these objects spans about 13 orders of magnitude. The result of this interpolation is shown in Fig. 2. We can see that ~100 km-sized objects have an average distance of about 2000 times the distance between the Sun and the Earth (known to astronomers as the astronomical unit, or AU).

Fig. 2: Radius of nomadic world versus the estimated average distance to the object

This is a fairly large distance, over 400 times the distance to Jupiter and about five times farther away than the putative Planet 9 (~380 AU) (Brown & Batygin, 2021). It is important to keep in mind that this is a rough statistical estimate for the average distance, meaning that the ~100 km-sized objects might be discovered much closer or farther away than the estimate. However, in the absence of observational data, such an estimate provides us with a starting point for exploring the question of whether a mission to such an object is feasible.

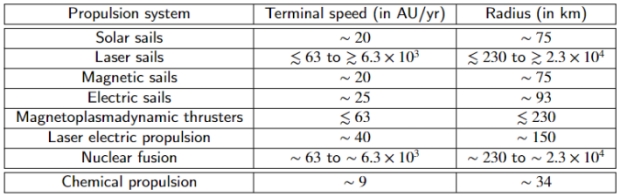

We use such estimates to investigate further whether a spacecraft with an existing or near-term propulsion system may be capable of reaching a nomadic world within a timeframe of 50 years. The result can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1: Average radius of nomadic world reachable with a given propulsion system in 50 years

It turns out that chemical propulsion combined with various gravity assist maneuvers is not able to reach such objects within 50 years. Solar sails and magnetic sails also fall short, although they come close (~75 km radius of nomadic object).

However, electric sails seem to be able to reach nomadic worlds close to the desired size and already have a reasonably high technology readiness level. Electric sails exploit the interaction between charged wires and the solar wind. The solar wind consists of various charged particles such as protons which are deflected by the electric field of the wires, leading to a transfer of momentum, thereby accelerating the sail. Proposed by Pekka Janhunen in 2004 (Janhunen, 2004), electric sails have also been considered for interplanetary travel and even into interstellar space (Quarta & Mengali, 2010; Janhunen et al., 2014). Up to 25 astronomical units (AU) per year seem to be achievable with realistic designs (Janhunen & Sandroos, 2007). Electric sail prototypes are currently being prepared for in-space testing (Iakubivskyi et al., 2020). Previous attempts to deploy an electric sail by the ESTCube-1 CubeSat mission in 2013 and Aalto-1 in 2022 were not successful (Slavinskis et al., 2015; Praks et al., 2021).

It turns out that more advanced propulsion systems are required, if we want to have a statistically good chance of reaching nomadic worlds significantly larger than 100 km radius. Laser electric propulsion and magnetoplasmadynamic (MPD) thrusters would get us to objects of 150 and 230 km respectively. Laser electric propulsion uses lasers to beam power to a spacecraft with an electric propulsion system, thereby removing a key bottleneck of providing power to an electric propulsion system in deep space (Brophy et al., 2018). MPD thrusters would be capable of providing high specific impulse and/or high thrust (the VASIMR engine is an example), although it remains to be seen how sufficient power can be generated in deep space or sufficient velocities be reached in the inner solar system by solar power.

Reaching even larger objects (i.e., getting to significantly further distances) requires propulsion systems which are potentially interstellar capable: nuclear fusion and laser sails, as the closest such objects might be at distances of as much as a light year off. These propulsion systems could even reach nomadic worlds of a similar size as Earth, nomadic worlds comparable to those we have already discovered. The average distance to such objects should still be a few times smaller than the distance to other star systems (~105 AU from the solar system, versus Proxima Centauri, for example, at about 270,000 AU). Hence, it is no surprise that the propulsion systems (fusion and laser sail) have a sufficient performance to reach large nomadic planets in less than 50 years, although the maturity of these propulsion system is at present fairly low.

Laser electric propulsion and MPD propulsion are also on the horizon, although there are significant development challenges ahead to reach sufficient performance at the system level, integrated with the power subsystem.

What does this mean? The first conclusion we draw is that while we develop more and more advanced propulsion systems, we become capable of reaching larger and larger (and potentially more interesting) objects in interstellar space. At present, electric sails appear to be the most promising propulsion system for nomadic planet exploration, possessing sufficient performance and a reasonably high maturity at the component level.

Second, instead of seeing interstellar space as a void with other star systems as the only relevant target, we now have a quasi-continuum of exploration-worthy objects at different distances beyond the boundary of the solar system. While star systems have been “first-class citizens” so far with no “second-class citizens” in sight, we might now be in a situation where a true class of “second-class citizens” has emerged. Finding these close nomads will be a technological and observational challenge for the next few decades.

Third, and this might be controversial, the boundary defining interstellar travel is destabilized. While traditionally interstellar travel has been treated primarily as travel from one star system to another, we might need to expand its scope to include travel to the “in-between” objects. This would include travel to aforementioned objects, but we might also discover planetary systems associated with free-floating brown dwarfs. It seems likely that nomadic worlds are orbited by moons, similar to planets in our solar system. Hence, is interstellar travel if and only if we travel between two stars, where stars are objects maintaining sustained nuclear fusion? How shall we call travel to nomadic worlds then? Shall we call this type of travel “transstellar” travel, i.e. travel beyond a star, or in-between-stellar travel?

Furthermore, nomadic worlds have likely formed in a star system of origin (although they may have formed at the end, rather than at the beginning, of the stellar main sequence). To what extent are we visiting that star system of origin by visiting the nomadic world? Inspecting a souvenir from a faraway place is not the same as being at that place. Nevertheless, the demarcation line is not as clear as it seems. Are we visiting another star system if and only if we visit one of its gravitationally bound objects? While these are seemingly semantic questions, they also harken back to the question of why we are attempting interstellar travel in the first place. Is traveling to another star an achievement by itself, is it the science value, or potential future settlement? Having a clearer understanding of the intrinsic value of interstellar travel may also qualify how far traveling to interstellar objects and nomadic worlds is different or similar.

We started this article with the analogy of driftwood between islands. While the interstellar community has been focusing mainly on star systems as primary targets for interstellar travel, we have argued that the existence of interstellar objects and nomadic worlds opens entirely new possibilities for missions between the stars, beyond an individual star system (in-between-stellar or transstellar travel). The driftwood may become by itself a worthy target of exploration. We also argued that we may have to revisit the very notion of interstellar travel, as its demarcation line has been rendered fuzzy.

References

Abramov, O., & Mojzsis, S. J. (2011). Abodes for life in carbonaceous asteroids?. Icarus, 213(1), 273-279.

Bannister, M. T., Bhandare, A., Dybczy?ski, P. A., Fitzsimmons, A., Guilbert-Lepoutre, A., Jedicke, R., … & Ye, Q. (2019). The natural history of ‘Oumuamua. Nature astronomy, 3(7), 594-602.

Brophy, J., Polk, J., Alkalai, L., Nesmith, B., Grandidier, J., & Lubin, P. (2018). A Breakthrough Propulsion Architecture for Interstellar Precursor Missions: Phase I Final Report (No. HQ-E-DAA-TN58806).

Brown, M. E., & Batygin, K. (2021). The Orbit of Planet Nine. The Astronomical Journal, 162(5), 219.

de León, J., Licandro, J., Serra-Ricart, M., Cabrera-Lavers, A., Font Serra, J., Scarpa, R., … & de la Fuente Marcos, R. (2019). Interstellar visitors: a physical characterization of comet C/2019 Q4 (Borisov) with OSIRIS at the 10.4 m GTC. Research Notes of the American Astronomical Society, 3(9), 131.

Hein, A. M., Eubanks, T. M., Lingam, M., Hibberd, A., Fries, D., Schneider, J., … & Dachwald, B. (2022). Interstellar now! Missions to explore nearby interstellar objects. Advances in Space Research, 69(1), 402-414.

Iakubivskyi, I., Janhunen, P., Praks, J., Allik, V., Bussov, K., Clayhills, B., … & Slavinskis, A. (2020). Coulomb drag propulsion experiments of ESTCube-2 and FORESAIL-1. Acta Astronautica, 177, 771-783.

Janhunen, P. (2004). Electric sail for spacecraft propulsion. Journal of Propulsion and Power, 20(4), 763-764.

Janhunen, P., Lebreton, J. P., Merikallio, S., Paton, M., Mengali, G., & Quarta, A. A. (2014). Fast E-sail Uranus entry probe mission. Planetary and Space Science, 104, 141-146.

Janhunen, P., & Sandroos, A. (2007, March). Simulation study of solar wind push on a charged wire: basis of solar wind electric sail propulsion. In Annales Geophysicae (Vol. 25, No. 3, pp. 755-767). Copernicus GmbH.

Jewitt, D., & Seligman, D. Z. (2022). The Interstellar Interlopers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.08182.

Lingam, M., & Loeb, A. (2019). Subsurface exolife. International Journal of Astrobiology, 18(2), 112-141.

Praks, J., Mughal, M. R., Vainio, R., Janhunen, P., Envall, J., Oleynik, P., … & Virtanen, A. (2021). Aalto-1, multi-payload CubeSat: Design, integration and launch. Acta Astronautica, 187, 370-383.

Quarta, A. A., & Mengali, G. (2010). Electric sail mission analysis for outer solar system exploration. Journal of guidance, control, and dynamics, 33(3), 740-755.

Slavinskis, A., Pajusalu, M., Kuuste, H., Ilbis, E., Eenmäe, T., Sünter, I., … & Noorma, M. (2015). ESTCube-1 in-orbit experience and lessons learned. IEEE aerospace and electronic systems magazine, 30(8), 12-22.

Westphal, A. J., Stroud, R. M., Bechtel, H. A., Brenker, F. E., Butterworth, A. L., Flynn, G. J., … & 30714 Stardust@ home dusters. (2014). Evidence for interstellar origin of seven dust particles collected by the Stardust spacecraft. Science, 345(6198), 786-791.

Getting to the solar gravity lens line would allow us to scan a section of the heavens and at least get a statistical representation of the number of objects and their sizes. We don’t just need to see a planet to get a huge amount of information of the universe with this remarkable technique.

The Solar Gravity Lens is highly direction radially out from the Sun. Scanning isn’t possible. At least it’s not possible around the Sun on a meaningful time frame. However that’s the Sun. Given an compact object an observatory on an elliptical orbit that dips in close enough, the orbit will precess in a reasonable time and ultimately scan the whole sky, with the occasional plane change.

It would be nice if we had object in orbit around the sun at around 550 AU which we could then enter into orbit around and cruise through space scanning. But even if we are going out in an arc there is still a region were objects can be seen which can be quite large.

If by serendipity we detect a nearby black hole closer to the sun than Proxima, then a BH gravity line telescope would be in a much closer orbit than the SGL distance of 550 AU. This BH would allow for a high-resolution telescope that would likely be able to scan the sky in a reasonable time frame. [Maybe that is where ETIs have parked their “lurkers”. ]

The SGL telescope uses the Einstein Ring of the sun to collimate the light to act as a primary mirror with a diameter greater than the sun’s diameter to gain the resolving power. However, placing mirrors in space separated by their orbit (e.g. 1 AU) could, in theory, provide a resolving power far greater than the gravity scope, with the time to deploy much faster and, more importantly, able to image far more targets. The data from each mirror would be sent to Earth and using timestamps and other techniques, the data from all the mirrors would be integrated to make an interferometer. [My guess is that computing power and techniques may well be available well before a probe with a telescope can even reach the start of the SGL.]

One would need a lot of mirrors to get the needed light collection, and they might well need coronographs too (a technique that will probably have be worked out in advance). With space manufacturing of the required many large mirrors to drive down costs, such a telescope system might obsolete an SGL telescope as the observation cost per target is amortized over many targets, rather than the single or few that an SGL telescope can offer. For stars, just 2 such telescopes may be required to provide a very high-resolution image from the reassembled interferometry data. A test might be done by placing the 2 mirrors nearby in L4 and L5 orbits. Their separation would be about 1/2 the diameter of the sun. Facing away from the sun, the 2 mirrors would scan targets in a 360 degree circle every 28 days, and could cover a band of the sky over a number of years.

I think it was Sara Seager who had suggested that we should look at target stars that would see Earth transiting the sun. This computational interferometer could look back at those target stars, and at least do some spectrometry of any HZ planets, even if the light gathering was too low to image a planet, even with a coronagraph.

If such a test was done and worked, then it could be extended with mirrors placed at L4 and L5 wrt to the sun-Earth, offering a separation over 180x that of the sun’s diameter. Very precise positioning would be needed to create the data needed for interferometry, but that is an engineering problem to solve.

If the astronomer commentators could explain why this is not theoretically possible (rather than technically) I would appreciate the response.

Even could send out a few of these timestamped mirrored craft along the SFL manifold with a comms and central processor unit, we get the enormous resolution first and then more magnification as we get further out. We get info much faster but it would required high precision maneuvering techniques I would think.

The objective is laudable but I question the means. The faster you go the faster you get there, except these are flybys with limited science value. That’s great for testing propulsion and instrumentation, however, for the best science return, we need high velocity and high deceleration. We don’t necessarily have to orbit the object, just slow down enough that a substantial amount of scientifically valuable data can be collected and returned.

Dear Ron, thanks for your comment regarding deceleration! Our focus in the paper was to see whether we can fly to these objects at all and we have not looked into maximizing the science return. This would be a nice topic for a future paper. The luminosity, distance during flyby, flyby duration, and instrument would determine the data we could acquire. From our previous paper (Hein, A. M., Eubanks, T. M., Lingam, M., Hibberd, A., Fries, D., Schneider, J., … & Dachwald, B. (2022). Interstellar now! Missions to explore nearby interstellar objects. Advances in Space Research, 69(1), 402-414.), where we looked at ‘Oumuamua’s detectability in deep space, I would not outright exclude that a flyby could not yield similar data as New Horizon during the Pluto flyby.

There may also be rogue black holes between Sol and Alpha Centauri…

https://www.space.com/rogue-black-hole-isolated-discovery

https://mashable.com/article/black-holes-rogue-discovery-space

Or how about a wandering WorldShip while we are at it…

https://centauri-dreams.org/2011/08/31/colonizing-the-galaxy-using-world-ships/

https://sciencefictionruminations.com/sci-fi-article-index/list-of-generation-ship-novels-and-short-stories/

http://www.astrosociology.org/Library/PDF/Caroti_SPESIF2009.pdf

Thank you, ljk for your comment! It is indeed interesting to speculate about other potential objects in interstellar space. My colleague Manasvi Lingam has published on the detectability of world ships:

Lingam, M., & Loeb, A. (2017). Fast radio bursts from extragalactic light sails. The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 837(2), L23.

It would be exciting to see what future observations might reveal.

I remember when this “rogue” BH estimate was published, and I did a quick mental calculation of the density. 100 million in our galaxy sounds like a lot but consider the volume of the Milky Way. Let’s use round numbers, which can always be refined if one cares.

10^5 x 10^5 x 10^4 = 10^14 ly^3

With 10^8 BH in that volume you need a cube 100 ly on a side to contain each BH, for an equal distribution.

It is highly unlikely that there’s a rogue BH in our neighborhood. If there was one, it is far more likely to be detected than a rogue planet, although there are more of the latter. BD’s, also very numerous, are easier to detect at a distance of several ly.

Tell that to Voyager 6, Ron. ;^)

https://memory-alpha.fandom.com/wiki/Voyager_6

How warm can a rogue planet get? Conceptually there could be a rogue Io out there, heated according to the orbital resonances of a larger body, or you could have two super-Earths in an elliptical orbit for a little while; also flares around a red dwarf can heat a planet enough for geological activity (see https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/2041-8213/aca287 – illustrating a magnetic means of heating) … but is there any plausible scenario that delivers enough heat for an Earthlike rogue planet or its moon to exist for a geologic span with liquid water at the surface under an only moderately thick atmosphere? Note radiation of infrared light (‘anti-solar cells’) might power a reasonably familiar ecosystem…

Thanks Mike for your comment! The idea of a rogue Io orbiting a larger rogue planet is intriguing. Regarding the presence of liquid water on rogue planets, this paper might provide some answers:

Lingam, M., & Loeb, A. (2019). Subsurface exolife. International Journal of Astrobiology, 18(2), 112-141.

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1711.09908.pdf

While surface water does not seem likely, subsurface liquid water might be possible.

Fascinating – thanks! They estimate that “the

primordial Earth might have retained a global subsurface ocean if it had become a free-floating planet”, based on a gamma factor of 4 for radiogenic heating. If hydrothermal vent abiogenesis turns out to be true, then life might have started on such a rogue planet exactly the same way as on our Earth? The study leaves part of my question in play in that “the effects of tidal heating are assumed to be negligible in our model, unlike Europa and Enceladus…”

Tangential to this post is the question of the nature of these objects. Are they “driftwood” from another star, or have they formed in situ in interstellar space? Are they part of an Oort cloud loosely bound to a star or expelled from another star (or both)?

If Oort cloud objects do they represent the same objects – just the larger ones – in the cloud?

It has been suggested that the Oort cloud can interact with the cloud in the next star system, exchanging objects. If you extrapolate the size/distance line, does it match the size/distance of Oort cloud objects?

Thanks Alex, Marshall can probably say more about this. There are indeed hypothesis on how these objects might have formed in-situ. Although, it is likely that most objects are ejecta. The cross-section of objects aggregating in interstellar space is very large compared to the one close to a star.

Terribly interesting to consider those objects beyond the Heliopause, especially to size, locate, and assess their constituents; but, to assess the interstellar matter/ debris/ leavings amongst the plasma on the leading edge of our heliosphere-as we glide through the galaxyISM- the ultimate in all exo-solar-archeological digs (or filtering exercises as the case may be). To trawl and dredge the various regions outboard of the termination shock, sampling all within the likely zones of stagnation for all means interstellar evidence.

I, for one, embrace the need to journey and view beyond our voyaging shell, but what better way to truly understand the actual substances beyond than to feature a mission that ‘drags’ over a great area, while ‘surfing’ the leading edge of the sheath.

Very interesting article. I miss some interesting destinations between stars, like objects in the Oort Cloud or the Detached Disc. Also, I don’t consider VASIMR a credible propulsion option for nomadic worlds. It would require an energy source not available now nor for some decades (a hugely efficient nuclear reactor or whatever). And, even if we had that source, it would be better to use it with current ion thrusters than VASIMR. They have much better Isp.

Thanks for your comments, Antonio! These are interesting points and including Oort Cloud and Detached Disc objects would indeed be interesting, although they would be somehow bound to the solar system.

Regarding VASIMR I agree and that is the reason why we conder it lower maturity than, e.g. the electric sail.

Regarding the question of mission goals. If the objects are Oort cloud objects, just ones in the larger size range, are they that interesting? Would they be that different from Kuiper Belt objects that are much closer, or Oort-origin comets that are pristine on their first visit?

IMO, the object type is perhaps more important. A planet-sized object is perhaps more interesting, especially of gas- or ice-giant size, as the furthest planet in our system is Neptune and reachable with even chemical rockets. A Brown Dwarf is the most interesting of all, as this is an object we have no close access to, and such a star/planet with moons would be a very intriguing target. However, unless we are very lucky, such objects may be as far away as the stars and therefore not reachable by any of the propulsion technologies other than laser sails and fusion rockets.

Regarding propulsion, I am skeptical of the laser electric propulsion idea. If the laser must provide energy in interstellar space, that is a very long distance to ensure sufficient energy reaches the craft, and that is before the “pointing issue” that was the subject of a few posts ago. Remember that the laser sail propulsion to be used by Breakthrough Starshot is a very high-energy beam that provides propulsion for a very short period near Earth, not one like Robert Forward’s beamed solar sails that provides energy all the way to the next star.

Reaching any target is going to be more satisfactory from a scientific perspective than remote observation, but I do wonder what really large telescopes can offer as the technology to extract information from em emissions continues to improve. Once built, they have the advantage that each target can be sampled and analyzed quickly with a delay of many decades. Tradeoffs as always.

Using eqn 3 in the paper, I calculate a low-mass brown dwarf of approximately 10x Jupiter’s mass would be 33 ly distant. Larger BDs would be that much further.

This seems counter-intuitive as Red Dwarfs are far more common than larger stars, and therefore one might assume that smaller stars and planets would be more common and therefore closer. If the authors are correct, it suggests that these nomadic planets between stars are far less common than planets and stars generally, which implies (to me) that BDs must be formed in star systems and rarely ejected, rather than forming in situ in space, or that they are too small to commonly aggregate and collapse nebula material.

The authors offer that their analysis is only a crude estimate and note this caveat:

In any case, if their analysis is in any way accurate for such bodies, it makes little sense to think of a nomadic/rogue Jupiter-sized body and above as being closer than the nearer stars and reachable by the proposed propulsion methods within 50 years. Only much smaller bodies might be reachable, and they might be very hard to detect with micro-lensing even as the technology to do so improves in the future.

This seems to me to suggest that the best method remains to wait for bodies to intrude into our system, and be detectable anywhere within the Kuiper belt and then send a probe to intercept, as has been proposed in other papers by Hein et al. To use an analogy, when trying to catch swimming marine animals, it is easier to use nets rather than by swimming after them.

Alex, we can see the brown dwarfs near us, as they are (relatively) bright in the IR. The closest is Luhman 16 AB, 6.5166 ± 0.0013 light-years from us and only 3.577 ly from Alpha Centauri AB. That, indeed, does not seem that close, but is comparable to the distance of the closest red dwarfs. There has been speculation of (and lots of arguments about) a “brown dwarf desert” based on stellar (bound) exoplanet data, but it’s not clear if that indicates a lack of brown dwarfs, or their loss by some mechanism. However, there do seem to be a reasonable number of nomadic Jupiters in the microlensing data, and thus some reason to hope that there might be some of these relatively close to the Sun.

M. E.,

Thanks for tracking that brown dwarf distribution. Had to wonder about that too.

But with regard to brown dwarfs and Jupiters at large, how would we be able to tell the difference in interstellar space? Our ability to distinguish them in star systems is based on doppler shifts and astrometry. In transit they would look more or less the same since their equilibrium diameters are about the same. How this is distinguished in micro-lensing, – well, I have difficulty with the details of microlensing every time I encounter it in discussion. As for deep space observation of lone BDs and Jupiters, their radiative signatures after an eon of flight would differ considerably since the Jupiter case would not have the same internal energy sources – unless we are missing something about another state of collapse. But I would suspect that the effective searches for the two would need to be or could be in different E-M bands.

This article sent me scurrying in search of quantified descriptions of the Oort Cloud and Kuiper Belt. Unfortunately, though both regions are described as substantial in mass ( e.g., the former a fraction of 50-100 masses of the Earth – but not as much as thought formerly) and dimensions ( radius from 10,000 AUs to about a parsec or 206,000 AUs), you might say the reports are forensic, like evidence at the scene of a crime: infalling comets attributed to distant past collisions, suggesting many more.

The New Horizons flyby of Arrokoth ( or Ultima Thule) gave a glimpse of a raw Kuiper Belt object, a reddish object full of cryo-ices and tholins. I would suspect that Oort Cloud objects would be very similar.

A catalog of Kuiper Belt objects exists, including some large ones, but I am unaware of any specific Oort Cloud specimens – unless they are very long period comets – ant then they are no longer “pristine” if they have passed close to the sun.

So, unless there are other candidates identified, to immediate objective, and assuming we have a spacecraft and propulsion, I would make a recommendation of heading for Sedna. It’s about 1000 kilometer wide object at low inclination and approaches within 85 AU of the sun, on a very elliptical path between 76 and 940 AU. Possibly another flyby can be arranged in route. This object is not a brown dwarf or a wandering planet, but it would be a well-defined precursor mission for more intriguing targets – should we ever identify them with our increasingly sensitive observatories. Signatures should be prominent in the infra-red or millimeter band.

Thanks for this comment, wdk! You may find this paper on mission opportunities to Sedna interesting: Zubko, V.A.; Sukhanov, A.A.; Fedyaev, K.S.; Koryanov, V.V.; Belyaev, A.A. (October 2021). “Analysis of mission opportunities to Sedna in 2029–2034”. Advances in Space Research. 68 (7)

The mere idea of stepping stones to Proxima Centauri is mind blowing! Imagine a map of all the numerous objects of various sizes inhabiting the 270,000 AU between Earth and Proxima. How many way points might there be and of what sizes and types? Some brown dwarf mini planetary systems, a few mini black holes, some solitary Earth-sized planets and myriads of mini planets?? I wonder what kind of telescope would be needed to detect these with some efficiency – we would certainly need to have a map of them before flying to Proxima – to get near them but not too close!

Dear Kamal, Thank you for your comment! It is indeed an interesting question of what means of detection would be needed for these objects. We did not address this question at this point in the paper.

Calculated distances to various bodies and their number within the distance to Proxima, based on equations 3 and 4 in the paper.

Name Radius D (AU) D(pc) D(ly) Npc (Proxima)

Sedna 1000 13400 .065 0.21 8100

Triton 1353 18130 .088 0.29 3270

Mercury 2440 32696 .159 0.52 558

Earth 6871 92071 .446 1.46 25

Neptune 24622 329935 1.6 5.22 .543

Jupiter 69911 936807 4.5 14.81 .024

BD Gliese 229B 76902 1030488 4.996 16.29 .018

Sun 695700 9322380 45.2 147 .41

The equations break down over larger bodies. Even Jupiter-sized bodies and cool brown dwarfs/rogue planets may be as far away as the nearer stars rather than within that volume of space.

A list of known and candidate cool brown dwarfs/rogue planets.. Most are fairly distant, although WISE 0855 is only about 7 ly away.

As the paper notes, detecting bodies of various radii is problematic even for our latest telescopes. As the authors note about detection:

This is important, as any spacecraft must have information on its target before launch. We, therefore, have a conundrum – how do we even detect these ISOs to launch fast probes to meet them?

Most of the paper then looks at various propulsion technologies to reach targets assuming we know where they are. What seems clear is that we have no near-term high TRL-level propulsion technologies to reach the more interesting ISOs assuming we detect them. We can reach the many smaller bodies that are expected to be very numerous, although these may be more of the same that we have reached with New Horizon’s flyby in the Kuiper Belt.

The question in my mind is whether these ISOs are worthy scientific targets to develop new technologies to detect and reach or justification for developing propulsion technologies that will not reach the nearest star in a 50-year period and therefore need these mission goals. Given the time frames, do we focus resources on better detection technologies to identify targets, on propulsion technologies, or both simultaneously? OTOH, if current and near-term technology drive the direction of discovery, are we better off focusing on other areas, such as biosignature detection? If we can detect exoplanets with strong biosignatures, would we best develop technologies such as an SGL telescope to image the exoplanets, possibly even to detect intelligent em emissions and artifacts? If so, we only need to develop propulsion technologies to place a telescope on the SGL (starting at 550 AU) and accumulate the data to image the target world, a development that allows for different propulsion technologies to achieve this goal depending on the acceptable mission time. It might even be worth testing Kipping’s Terrascope concept first, even though it would not generate the resolution of an SGL telescope, but would be far less expensive to develop and deploy quickly.

To me, the bigger picture remains that physical contact between the stars is extremely difficult and hence isolating (“God’s method of quarantining”). For humans, even with extended lifetimes, and perhaps some hibernation, the timelines are so long that generations may elapse before results can be achieved. Do we have the patience and institutions that allowed multi-generational medieval cathedral building? The technology to build cathedrals didn’t change that much, other than the addition of buttresses to create open volumes of interior space [Simplistic as there were others] and the economy did not change much during construction except in response to war, pestilence, and harvests. This is not true today as technologies rapidly change, as do social systems. The 40+ years of the 2 Voyager probes suggest that machines are the best means to maintain vigilance over long periods, although the technologies have vastly changed since their launch. Any 50-year mission to some ISO is going to face the same issues – the hardware and software will vastly improve over the mission time. While we cannot do much about the hardware after launch, can we “future-proof” the craft to be able to handle newer computer languages and more capable software? As Vernor Vinge suggested in his Zones of Thought novels, would newer software be added as newer layers over old software so that older, lower-level software would not need to be rewritten? Interoperability between computer languages is increasingly common today, suggesting that older languages, interfacing with the metal can be controlled by languages that do not, avoiding the need to understand the older language, just enough to understand how to control it and pass data to and from it.

The computer language is irrelevant. What a human programs in is ultimately translated to object code that runs directly on the target hardware. The system is multi-layered with more permanent “firmware” that manages the operating environment, but is rarely a general purpose OS (for good reasons). Uploading new object code and data to spacecraft typically goes through several steps:

-Reception: This includes error detection and correction (if appropriate), or request for retransmission.

-Storage: The new software must be stored, and that may be in short supply. This is inevitable since (obviously) it is comparable size to the existing software. The storage of the received software must also be validated since memory is fragile in a space environment. Updates must be done in phases when all the new software will not fit.

-Watcher: You want at least redundancy or a separate watcher system in case something goes wrong, which it often does. Only when the system with the new software has been booted and validated will it be loaded onto the redundant systems. Even then things can go wrong. They have to play nice with each other when at different versions.

-Disagreements: Timing and actions by different systems can cause conflicts, either as expected or due to previously undetected faults, cosmic rays or other deterioration. No two systems are ever identical.

Well, there’s lots more of this. Older spacecraft could not be updated at all or had no fallback from errors in uploaded software. There are similar Earth-bound systems in critical systems, but spacecraft have their unique requirements.

NASA and their peers have been dealing with this for decades. Unfortunately, as we’ve seen, old code and documentation archives may be inadvertently destroyed years after the team is disbanded on mission completion. The extra years interval expected with interstellar missions will only make the problem worse. Updates may become too risky.

@Ron S.

“The computer language is irrelevant. ” Isn’t this irrelevance really the product of people making a language cause they want to make a name for themselves and not cause a new language is really an advancement ?

charlie, you’re being overly cynical. Certainly that happens but it is far from the norm. Languages like that soon die out.

Languages are like the tools in a toolkit. You pick the one most suitable for the job at hand. You can use needle nose pliers to loosen a hex-head bolt but it’s better to use a socket wrench.

Languages are an advancement when they improve usage of new processors and peripherals, or to simplify programming, make it easy to avoid making mistake, optimizing resource usage, or whatever else you can think of.

But many times in mission critical applications you might use a relatively ancient language because it is well tested, stable and highly predictable for the target hardware.

I defer to your superior knowledge of space related systems, but I don’t think what you have said invalidates what I said, and in addition, is possibly even not fully correct.

IIRC, Voyager’s software was written in Fortran and a later version of Fortran was used. IDK what effect that had on the hardware, but clearly it was successful.

Not all software must be compiled to object code or lower. If the software instructions are interpreted, only the interpreter must be present and unchanging, so the lower-level code is not changed. Yes, that means it is slower, but it does offer more flexibility. We already have many computer languages that are interpreted or run in virtual machines and do not need to compile the new code. In addition, languages that can interoperate with lower-level languages like C can avoid rewriting low-level routines. If one can build an interpreter that is constructed on top of an interpreter, then there is no reason why this might not be stacked like so many layers, none of which touch or change the instructions to run on the hardware. Yes, it is ridiculously inefficient, but computing capabilities continue to increase making this less of a problem.

Another way to avoid changing the code is to use code that works like an artificial neural network. The network functions on the connection weights which can be stored separately. Thus a library of stored weights changes the way the network functions. Storage of the different weight matrices is the limiting factor.

Ideally, spacecraft software will partially operate like human wetware. We can learn different spoken and written languages, logic, maths, and a host of things that are effectively like DSLs. We can learn new functions by interfacing via our existing sensory system and can deploy specific tools where they perform faster and better than our more flexible brains. If probe systems were like our wetware, they could upgrade their wetware by just adding new instructions that are sent to them.

This is of course not what we do with our probes and rovers today, where performance is vital and mimics the approach that rocket scientists and engineers built launchers, an approach that is being overturned with an economics approach and reusability.

None of what I say above is any more fanciful than the comment regarding George Church’s bio-fantasy of biological systems designing communication systems on exoplanets, and arguably within the realm of reality even today.

Alex, I am very familiar with interpretters and I even developed one decades ago. In my post-graduate work we touched on the then holy grail of a universal virtual machine that would be compatible with any high level language and processor architecture. It turned out to be so difficult as to be a waste of effort.

Complexity like interpretters and much of what we have running on our desktops is not only overkill for current spacecraft needs, that complexity encompasses a huge reliability risk. Embedded systems typically strip out everything superfluous to the strict application requirements for this reason. There are many Linux versions structured for this very purpose, to make it convenient to pick and choose components for ordinary (Earth-bound) embedded software, examples of which are probably to be found throughout your home, vehicle, phone, etc.

BTW, C is not really a “low level” language. It is structured in a way that there is usually a reasonably direct mapping from language structure and elements to most processor architectures. That makes it easier to compile with a predictable result. It isn’t necessarily more efficient to run than some interpretted languages, but the risk is greater in mission critical systems because the interpretter multiplies the failure potential. Not what you want in a spacecraft.

Ron, I am not sure whether we are talking past each other. My sense is you are explaining how and why we build spacecraft systems now, primarily for relatively short lives, and I am trying to suggest that long-lived craft should be designed differently (however difficult) to allow for technological development over the mission time and beyond.

Consider the Voyager spacecraft, designed originally to fly by Jupiter and Saturn (although the Grand Tour mission was largely carried out), their mission would have ended after 4 years in 1981. But Voyager 2 went on to Uranus and Neptune, which occurred in 1989, 12 years after launch. Yet here we are 45 years after launch and the Voyagers are still sending some data back from the edge of interstellar space, their systems carefully using the remaining energy of their RTGs. [Would beamed energy have allowed extending their lives?]

Had we known how long Voyager could last, would there have been any different design decisions made?

Now we are talking about 50-year missions, and no doubt in practice, as with all spacecraft that are designed to “guarantee” a defined minimum mission life, they will exceed their planned mission time. Over 50 years, how will technology back on Earth change?

If there was a way to add hardware after the fact, like the astronauts bringing laptop computers onto the Space Shuttle that were far more capable than the Shuttle’s computers, we would no doubt do that. But the only upgrades we can offer is new software (but maybe not?).

On Earth, as software systems, languages, and OSs proliferate faster than hardware is replaced, we upgrade our systems accordingly. OSs now automatically update, as do cloud-based applications. We add new languages to develop with, all targeted to the hardware and using storage space. Yes, there are issues with bugs, and testing is far less comprehensive than on avionics systems, but nevertheless, such upgrades do work for the vast majority of cases where the hardware can cope with the changes. Older hardware that reaches the limit of its capability is not updated [my older iPad has stopped updating its iOS and frozen cloud-based apps fail as the content no longer can be handled.].

When Voyager was designed, there were a handful of general computer languages. Fortran was the one chosen. This was about the same time as I was an undergraduate and Fortran was the language they were trying to teach the non-computer engineering undergrads. [Failed with me :( ]. Fortran is still used, although newer languages are now used for scientific computing, and ADA was/is being pushed for required-reliable systems like avionics. Nevertheless, warships with their far more extensive computer systems use “unreliable” OSs like MS Windows. (Did the ?USS Vincennes have to reboot its computers frequently as we did back then?) *nix OS flavors are used for more reliable systems. Financial institutions used propriety Unixes for backend systems, and web servers mostly rely on Linux as the OS core of the stack. (In the 1990s, where I worked, a Unix system was running for a year without needing to reboot, while MS Windows NT required rebooting sometimes more frequently than daily.) Programmable calculators in the 1970s using assembly rather like the Apollo computers, was a robust way of computing, although the size of the stored Apollo guidance software as printed out on paper was clearly a major task to perform. The Forth language was a direct upgrade from that approach and still has adherents today. But general-purpose programming does not rely on such low-level approaches as it is too inefficient for human labor. Languages have evolved to be ever higher level. Arguably AI-assisted coding with MS’ CoPilot is indicative of the next level of programming with an AI assistant rather than directly with the language, rather like GPT-X and ChatGPT and its ilk composing text with prompts.

As the annual surveys of computer languages show, the popularity and use of languages come in waves, with the surveys of most loved and hated languages an indication of future language use. Can we even guess what language and how it is used will be in 50 years? Impossible. What about hardware? What I do think might be possible with hardware is programmable hardware like FPGAs might just allow hardware to be reprogrammed to emulate newer hardware yet to be developed.

Some developments I think we can count on. Firstly that hardware will continue to improve, if not by Moore’s Law, then other approaches. It will be easy to load more storage space and computing power into any new spacecraft. As with New Horizons, the low bandwidth of transmission may require huge storage space for data. Adding excess storage might be the best way to allow adding new software to a spacecraft, just as hard disk space allows this on consumer computers. AI-assisted QA on a replica spacecraft might be the better way to test reliability before uploading to the spacecraft. (Would an AI have relieved the tedium of Ken Mattingly’s testing of procedures to limit the power demand of the crippled Apollo 13 systems and found a solution more quickly?) More storage and computation will increase reliability through redundancy. 50 years from now AI systems will be far more capable than they are today, and perhaps able to be more versatile in how they are trained so that an AI deployed on a spacecraft can upgrade its training without needing server farms and massive data sets. I would expect such AIs to run on neuromorphic hardware that may use a different substrate than a semiconductor crystal. If it does prove unreliable to add new, more expressive, computer languages to the spacecraft, then the new language will be compiled (by an AI?) into a language that can be used by the spacecraft. [Today I can prompt ChatGPT with English instructions to write a piece of code in a specified language of my choice. Future versions may be robust and accurate enough to do that for any computer language source code pair just as language translators do for spoken and written languages.]

In summary, I would expect that spacecraft on very long missions will be designed on the assumption that technology will change and that these changes will be beneficial to the operation of the craft as its mission proceeds.

[As a consumer, I would love to be able to have that flexibility in my own systems. From being able to swap out an x86 chip for an ARM chip and a software emulator layer (virtual machine?) to run all the compiled x86 software. Or a chip that can configure itself on demand to look like any chip design. Andrej Karpathy claims CoPilot writes 80% of the code he creates. I would love to be able to ask an AI assistant to convert source code language A to source code language B rather than having to install a new language compiler or VM on my computer. Perhaps this is part of the solution for future-proofing distant spacecraft.

Again, this is perhaps going far off into the weeds, so I’ll be brief.

Predictions about the future are difficult! It’s fun to speculate if we keep in mind that it’s just that: speculation. Certainly there will be improvements of many kinds – hardware, software, algorithms – but the fundamentals remain.

Perhaps the greatest challenge with a remote system, spacecraft on Earth, is reliability. Remote diagnostics and repair are possible within strict constraints. Having increased self-diagnosis and repair options, and especially fault tolerance built into the design, are good. All such systems involve added complexity and therefore more failure modes. There is no panacea. We will lose sophisticated spacecraft and we need to design exploration programs with that in mind.

@Ron S.

“charlie, you’re being overly cynical. ” True … absolutely. Partly due to my bad experience in college with intro. Fortran – soured me on comp. science. By the way, your an excellent tech writer on comp. science.

Same problem. Right off the bat, I didn’t understand how x = X + 1 made any sense. But the killer was the lack of feedback. Hand in a sheet of code and a few days later one got a thick, unexplainable stack trace due to some error.

It soured me on any coding until I was able to get rapid feedback. First with a punched paper tape programmable calculator, and then a year later with a programmable calculator. That last got me going until I bought my first computer, a ZX80 around 1979/1980. Never looked back.

@Alex

I’m still soured on any coding – the error messages are inexplicable to me. Error messages don’t seem to need to be that way ….

If you use a spreadsheet, then you are using a tool that allows you to code in an easy way, stringing together cells as an algorithm.

As for error messages, newer languages are far more helpful. Stacktraces indicate where the first occurrence of an error happens, and an IDE will often indicate the line where there are errors and even where exactly the error exists.

Looking at hex dumps of crashes was never something I could do, and I mostly use languages that don’t crash in the same way, for example stepping on memory locations.

Personally, I find automating things that would be tedious at best to do by hand and impossible at worst, very satisfying. Creative tool building, not just tool-using, is something that pushes my dopamine release.

Be careful not to generalize based on one person’s (your) personal experience.

This discussion is wandering far off topic so I’ll be brief. My experience is that a great deal of introductory (or minor subject) programming education is focussed on using a language and not on fundamentals. For example, algorithms, data management, data representation, hardware/software architecture, etc., that are the foundations of the field. Too many novices know something about using one language (or two) and have a limited understanding.

As a post-grad in the field, assisting the professors in their courses, I dealt with engineering and science students caught in this grind. It was both amusing and sad. I had to wonder whether it was more worth the trouble. I suppose it was but it also left a long trail of terribly misinformed and confused students.

“It was both amusing and sad. I had to wonder whether it was more worth the trouble. ”

believe you me, it wasn’t amusing it was sad

Dear Alex,

Thanks a lot for your always insightful comments. Indeed, the priority setting in the context of an interstellar exploration roadmap becomes more interesting now due to new alternatives.

Ultimately, this is probably going to be decided in a Decadal Survey-like process where various stakeholders will have a say, notably the science communities backing the alternatives unless private actors such as Breakthrough Initiatives would find private or public-private funding opportunities.

Detectability is a major issue for nomadic worlds and this will be addressed in future publications.

About cathedrals, see my Centauri Dreams post from 2020: https://centauri-dreams.org/2020/07/17/the-cathedral-and-the-starship-learning-from-the-middle-ages-for-future-long-duration-projects/

As you say, the Voyagers give us a glimpse at how sustaining a mission over a 50 year period might look like. Regarding software, what you describe with a reference to Vinge sounds a bit like how legacy systems are operated today by using wrappers and adapters to encapsulate them and to basically treat them as black boxes (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Legacy_system). I am not an expert in this but it depends on the interoperability on the syntactic and semantic level between the languages, which might be tricky (see Semantic Gap: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Semantic_gap).

Interesting article pointing out that “space”, though spacious, ain’t quite empty (depending of course, on one’s point of view). Even JWST got a hole in one mirror panel and earlier on had a profusion of micrometeorite impacts until it moved out of a problematic zone.

Sadly, the interval between the stepping-stones is substantially wider than our steps at the present normal off-earth pace. And mining remote bodies to construct copies of spacecraft may have to do without the offshoring of the technology to some Asia-equivalent.

Of course, the “Asia-equivalent” may be the culture that is running the exploration in this manner. We should always be aware that nations (and empires) both rise and fall (Britain being the most recent example) and the lead is passed or taken over by another. The best we can hope for is that western Enlightenment continues in some form or other, even if the social and political environment changes.

If interstellar travel becomes a reality in a few centuries, it is highly unlikely to be managed by the USA (if that polity still exists) or any culture that is recognizable as “American”, or even “Anglo”. The nation or culture may not even be one that exists today, although I would guess that it emerges from nations or cultures that are recognizable today.

Listen up, space cadets!

Contemplating your own trip out into nearby void? Here is some useful seat-of-the-pants navigation hints and mission planning data.

For stellar objects, star catalogs usually provide parallaxes (seconds of arc), proper motions (seconds of arc/yr) , position angles (degrees clockwise from N) and radial velocities (km/sec). Remember, positive RV’s indicate an object in recession.

A good catalog for objects within 5.0 pc is The Royal Astronomical Society of Canada Observer’s Handbook “Table of Nearest Stars”. This list is updated every year to reflect new discoveries. The 2023 Edition of the RASC Handbook lists 53 systems, including 66 stars, 9 brown dwarfs and 13 extrasolar planets. There appear to be a few high-velocity objects, like Barnard’s and Kapteyn’s Stars, but most of the entries appear to be drifting along in the LSR, with radial velocities (relative to the Sun) of the same order of magnitude as Solar Escape Velocity at Earth’s orbit.

Proper motion/parallax gives the velocity of the object across the line of sight in AU/yr. Convert this to km/sec, and with the PA and RV you have a good approximation to the motion of the object relative to our Sun; essential 3-D velocity information for making rendezvous.

Good luck on your mission!

It’s nice to have tables like this (their 2017 table is online at https://calgary.rasc.ca/nearbystars.htm ). But it’s frustrating for any space cadet to navigate by the long, seemingly meaningless sets of numbers we’re given. For example, you look up the list of nearest exoplanets in Wikipedia, and find Lacaille 9352. But it’s not on the RASC list … only by searching for the right ascension and declination can you find HD217987. Now learning one license plate number per star is hard enough, but two, three, four? Now we see why so many aspiring cadets end up in the red uniforms.

I just had this modest idea: let’s just name all the stars. In a way that can be traced back to the star without having to have a special table for every one. Then I was thinking it might be less controversial to name about 16 million constellations instead. We convert the right ascension and declination each to an integer between 1 and 4096 by a little basic math. Then we look up each from a list of common words ( https://github.com/Stegacite/stegacite lists 4096 mostly-English words that each start with a different first four characters).

Well, with a little spreadsheet rampage, I can now call the aforementioned system “Watch Fascinating”, or perhaps “Watch Fascists” if you’re in a more paranoid mood. (I alphabetized the word list, so the “W” recalls the 23h right ascension, and the “F” suggests a moderately negative declination. With 16 million constellations, there will still be some stars in the same one, so you’ll need to append a number of parsecs to the end of the name to specify a faraway system). Ross 128 is found in Lazy Limb. Gliese 1061/LHS 1565 can be described as Celestial Drip. My odds of yelling the right destination at the navcom while under heavy Kligon fire just went up a bit.

Welcome to the wonderful, wacky world of astronomical nomenclature!

As you have now no doubt discovered, Lacaille 9352 is listed in the 2023 RASC table as CD -36 15693. ‘CD’ is the Cordoba Durchmusterung catalog (no relation to my surname, its where the Argentine observatory where it was compiled is located) and the number is derived from the star’s position, (but from another Ep0ch!).

The HD 217987 designation refers to the Henry Draper catalog (once again, no relation to my Christian name).

This star is bright enough that it probably can be found in many other general catalogs under numerous aliases (such as the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory catalog where it appears as SAO 214301. It also probably appears in many specialized catalogs, especially if it is a binary, variable, has planets, an unusual spectrum, extreme proper motion, or some other characteristic of special interest to some investigator.

Many catalogs have cross-references to other catalogs, and you can always rely on the fact most listings are ordered by Right Ascension. Unfortunately these lists can be put out of order as precession scrambles the coordinate system, but that’s another story.

My Sky Catalog 2000.0 lists this star under 3 aliases, but it only goes to magnitude 8.0. If it had been a bit fainter, it would have been left out altogether.

And if you think stellar designations are confusing, wait till you start trying to track down information on faint, anonymous galaxies.

Any questions. cadet?

BTW, tracking down errors, contradictions, misidentifications and inconsistencies in catalog data has become a science in itself, with its own literature, leaders, and journals. It is pretty much dominated by amateurs, and these folks are doing valid, important scientific work. And it is so recognized by professional astronomers, who rely on this metadata maintenance, but have better things to do with their time.

Curses! I’d just came up with the notion of splitting each of the 4096 words into combinations of 16 constellation symbols plus a range modifier, and now you have to remind me that precession is making all of my Stargate addresses go out of date. :)

This wild interstellar picogram probe idea could carry engineered microbes to other stars

By Charles Q. Choi published about 5 hours ago

The microbes could build equipment once they landed on a planet, according to the wild concept.

Microbes carried by laser-propelled sails could serve as interstellar probes that can build communications stations to phone home from Alpha Centauri, suggests a scientist known for wanting to resurrect extinct woolly mammoths and use DNA to detect dark matter.

This concept from George Church, a geneticist at Harvard University, builds upon efforts to greatly speed up spaceflight. Current spacecraft usually take years to make trips within the solar system; for example, NASA’s New Horizons probe took nearly 10 years to reach Pluto.

In theory, spacecraft using conventional rockets would require thousands of years to complete an interstellar voyage. For instance, Alpha Centauri, the nearest star system to Earth, is located about 4.37 light-years away — more than 25.6 trillion miles (41.2 trillion kilometers), or more than 276,000 times the distance from Earth to the sun.

NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft, which launched in 1977 and reached interstellar space in 2012, would take about 75,000 years to reach Alpha Centauri even if the probe were headed in the right direction, which it’s not.

Full article here:

https://www.space.com/interstellar-probes-microbes-other-stars

To quote:

In addition, even if Starshot successfully launches “space-chips” at Alpha Centauri, without another laser at that destination, there is no way for them to slow down. This likely limits Starshot missions to flybys instead of landings.

Any Starshot probe attempt to land would likely prove catastrophic. Although the spacecraft are designed to be extraordinarily lightweight — each just 0.035 ounces (1 gram) or so — when traveling at 20% the speed of light, they would each pack as much energy as one-eight the atom bomb dropped on Hiroshima in World War II, Church noted.

Instead, Church suggested using probes a billion times lighter. If they did make impact, it would only pack as much energy as half a food calorie, he noted.

“A probe that lands is tremendously more valuable than one that flies by at great distance and for a very brief time,” Church told Space.com.

The paper online here:

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/ast.2022.0008

Dear ljk, Very interesting pointer to the article! Church has been working on interstellar travel for a while. This reminds me of Robert Zubrin’s idea to attach tiny sails to bacteria (~micro meter scale):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tzyrOk9Ymf8

Creating a bacterium that can turn into an interstellar laser requires some imagination, and remarkable skill in genetic engineering. It’s the stuff of science fiction, and if you can do that, you can do many dramatic things on Earth, beneficial or baneful. But if we spin the telescope around 180 degrees, this becomes an interesting science fiction scenario. If alien bacteria land and begin flashing a message in unison, perhaps requisitioning large amounts of local resources (stray children?) to do it, how do we respond? We might as well ask how we’d respond if their Starshot weapon starts raining down multiple nuclear-scale explosions… Things like this make it seem almost reassuring if Berserkers, standing mutely at attention, stand guard by the heliopause against signs of infection. Until Voyager 2 sets them off, that is. :)

I consider Church’s ideas fanciful – more fantasy than SciFi. Biology does not work like our technology and despite the use of biomimicry, I do not see any expectation that it will ever do so. Life has to do more than passively form a shape and function. When nanotechnology (c.f. Drexler’s nanobots) was being hyped in the 1980s it failed to materialize because nanobot-size life didn’t work like scaled-down mechanical systems. I have no doubt that we can eventually design new life forms, and alter the genetic system to handle new bases and amino acids, create new enzymes and pathways that might mimic components of our technology, but I don’t see how it can create biological versions of optical or radio telescopes, lasers, and other technology. Maybe I am not imaginative enough. LOFAR is a fairly low-tech radio telescope array. Could a field of future plants/macro fungi emulate it? If so how? This isn’t to say that some things cannot be done. I think the tangled rhizomes of grasses or fungal hyphae, could be made to emulate a neural network operating at a very slow speed. Could their leaves then become reflective enough and phased to send images across interstellar space? Create radio waves?

Hi Andreas

Fascinating work. Slowing down at the target is highly desirable. I hope by the time we’re targeting nomadic objects in between the stars, we’d also know if the Plasma Magnet performs as hoped, so we could consider braking against the LISM.

Hi Adam,

Good to hear from you! Yes, I agree, magnetic or electric sails could be used to slow down against the interstellar medium, which would just be a dual-use of the primary propulsion system if those are used. Electric sails seem to have a superior performance at lower speeds (< 5%c):

Perakis, N., & Hein, A. M. (2016). Combining magnetic and electric sails for interstellar deceleration. Acta Astronautica, 128, 13-20.

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Andreas-M-Hein/publication/295860468_Combining_Magnetic_and_Electric_Sails_for_Interstellar_Deceleration/links/56cef8e508ae85c82343150d/Combining-Magnetic-and-Electric-Sails-for-Interstellar-Deceleration.pdf

There’s no reason to think the relationship continues beyond Jupiter mass. Planetary mass objects (PMOs) and brown dwarfs are formed by the star formation mechanism. Smaller planets and objects are formed in the planet-forming disc, and some of them get ejected. Ejected objects tend to be the smaller bodies, leaving the massive planets still in orbit. Anyhow there are two types of bodies with no reason to think they form a continuous distribution with each other.

If such a thing exists, these rogue planets ought to have “dark matter hairs”. ( https://arxiv.org/abs/1507.07009 ). New Horizons observed (I think it was 2 sigma) an increase in background luminosity, which might be due to (axion?) dark matter, though this seems still under debate? ( https://arxiv.org/abs/2205.01079 ). Based on these ideas I went to Arxiv, and found a proposal to spot dark matter streams: https://arxiv.org/abs/2212.10905 Would a breakthrough there help us find nearby planets, rogue or otherwise?

Thanks Mike! Very interesting papers.