What do you get if you shake ice in a container with centimeter-wide stainless steel balls at temperature of –200 ?C? The answer is a kind of ice with implications for the outer Solar System. I just ran across an article in Science (citation below) that describes the resulting powder, a form of ‘amorphous ice,’ meaning ice that lacks the familiar crystalline arrangement of regular ice. There is no regularity here, no ordered structure. The two previously discovered types of amorphous ice – varying by their density – are uncommon on Earth but an apparently standard constituent of comets.

The new medium-density amorphous ice may well be produced on outer system moons, created through the shearing process that the researchers, led by Alexander Rosu-Finsen at University College London, produced in their lab work. There is a good overview of this water ‘frozen in time’ in a recent issue of Nature. The article quotes Christoph Salzmann (UCL), a co-author on the Science paper:

The team used a ball mill, a tool normally used to grind or blend materials in mineral processing, to grind down crystallized ice. Using a container with metal balls inside, they shook a small amount of ice about 20 times per second. The metal balls produced a ‘shear force’ on the ice, says Salzmann, breaking it down into a white powder.

Firing X-rays at the powder and measuring them as they bounced off — a process known as X-ray diffraction — allowed the team to work out its structure. The ice had a molecular density similar to that of liquid water, with no apparent ordered structure to the molecules — meaning that crystallinity was “destroyed”, says Salzmann. “You’re looking at a very disordered material.”

Disruptions in icy surfaces caused by the process would have implications for the interface between ice and liquid water that is presumed to exist on moons like Europa and Enceladus. The surface might be given to disruptions that would expose ocean beneath.

What goes on in the icy moons of the outer system is always of interest, especially given the astrobiological possibilities, and it was probably the thought of an ice giant orbiter at Uranus that triggered my interest in the amorphous ice issue. Kathleen Mandt (Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory) just wrote the former up in Science as well, noting how little we’ve learned since the solitary Voyager flyby of the planet in 1986. In addition to planetary structure and atmosphere, we could do with a lot more information about its moons and their possible liquid water oceans.

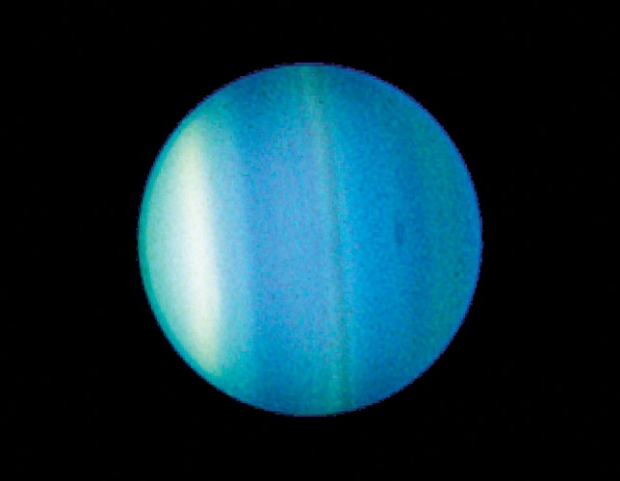

Image: This 2006 image taken by the Hubble Space Telescope shows bands and a new dark spot in Uranus’ atmosphere. Credit: NASA/Space Telescope Science Institute.

The planetary science decadal survey released in 2022, called Origins, Worlds, and Life, which reviewed over 500 white papers and 300 presentations over the course of its 176 meetings, flagged the need for such a mission in the coming decade, a planetary flagship mission as a next step forward after Europa Clipper. I don’t want to downplay the role of such a mission in deepening our understanding of ice giant formation and migration, not to mention the Uranian atmosphere, but the moon system here has proven an extreme challenge for observers. Its study becomes a major driver for the Uranus Orbiter and Probe (UOP) mission:

The system’s extreme obliquity…limits visibility of the moons to one hemisphere during southern and northern summers. Voyager 2 could only image the moons’ southern hemispheres, but what was seen was unexpected. The five largest moons, predicted to be cold dead worlds, all showed evidence of recent resurfacing, suggesting that geologic activity might be ongoing. One or more of these moons could have potentially habitable liquid water oceans under an ice shell, making them “ocean worlds.” Ariel, the most extensively resurfaced moon, is a strong ocean worlds candidate along with the two largest moons, Titania and Oberon… UOP will image and measure the composition of the full surfaces of the moons to search for ongoing geologic activity, and measure whether magnetic fields vary in their interiors owing to the presence of liquid water.

Miranda, Ariel, Umbriel, Titania and Oberon, the five largest moons of Uranus, could all contain subsurface oceans (and I don’t want to leave out of the UOP story the fact that it would carry a Uranus atmospheric probe designed to reach a depth of at least 1 bar in pressure, a fascinating investigation in itself). The decadal survey has recommended a launch by 2032 to take advantage of a Jupiter gravity assist that would allow arrival before the northern autumn equinox in 2050 for better study of the moon system. “The space science community has waited more than 30 years to explore the ice giants,” writes Mandt, “and missions to them will benefit many generations to come.”

The first of today’s papers is Rosu-Finsen et al., “Medium-density amorphous ice,” Science Vol. 379, No. 6631 (2 February 2023), pp. 474-478 (abstract). The Mandt article is “The first dedicated ice giants mission,” Science Vol. 379, No. 6633 (16 February 2023), pp. 640-642 (full text).

I’m not clear on teh relevance of the amorphous ice experiment.

1. A liquid ocean is not at -200C, so doesn’t the amorphous ice at the interface just undergo remelting and refreezing back into regular, terrestrial, structured ice?

2. If the density of this amorphous ice is about the same as water, what is the tendency to create an ice crust that floats on the liquid ocean?

I can see that this ice could appear in locations near the surface of the crust where shear forces might grind up the ice exposed to cold and vacuum, but I don’t see how it can exist at the ice-ocean interface.

The putative Uranus orbiter (and probe, if we are lucky) is the next

logical step in our collective survey of the solar system. If it can do a

Cassini and last a reasonable fraction of a Uranian season then all the

better. I expect the icy moons and rings to deliver lots of surprises too. Neptune/Triton will get their day as should another TNO like Eris, but this needs to happen first!

P

The tidal forces from Uranus keep the ice liquid oceans on it’s moons. I wonder what the JWST can do with it’s infra red spectrometer to study the chemical composition of Uranus’ moons. 2050 is a long time in the future.

Current orbital eccentricities are very low. 0.001-0.0015 with the exception of Umbiel(0.005). Umbriel’s orbit is nearly 100 hours. Slight orbital variations due to moon moon interaction will have undoubtedly created larger(and smaller) eccentricities in the past, but I wonder if remnant heat is large enough to have maintained any liquid ocean to present day.

Hi Paul

A Uranus Orbiter which uses gravity assists from the major moons just like “Galileo” did around Jupiter was reported in 2012 by David Portree here:

Galileo-style Uranus Tour (2003)

Based on this paper:

Feasibility of a Galileo-Style Tour of the Uranian Satellites

James Longuski has made it available on his Purdue U website.

Shocked comets maybe. I remember stories of chemical production via ball mills in phys.org in the past year-perhaps of more utility.

2050? Oy vey…

Scientists eye mission to Uranus: an alien world where the darkness of winter lasts 21 years

The US and Europe face the challenge of sending probes to the most unknown planet in the solar system by 2050

https://english.elpais.com/science-tech/2023-02-19/scientists-eye-mission-to-uranus-an-alien-world-where-the-darkness-of-winter-lasts-21-years.html