If we’re going to get to the stars, the path along the way has to go through an effort like Breakthrough Starshot. This is not to say that Breakthrough will achieve an interstellar mission, though its aspirational goal of reaching a nearby star like Proxima Centauri with a flight time of 20 years is one that takes the breath away. But aspirations are just that, and the point is, we need them no matter how far-fetched they seem to drive our ambition, sharpen our perspective and widen our analysis. Whether we achieve them in their initial formulation cannot be known until we try.

So let’s talk for a minute about what Starshot is and isn’t. It is not an attempt to use existing technologies to begin building a starship today. Yes, metal is being bent, but in laboratory experiments and simulated environments. No, rather than a construction project, Starshot is about clarifying where we are now, and projecting where we can expect to be within a reasonable time frame. In its early stages, it is about identifying the science issues that would enable us to use laser beaming to light up a sail and push it toward another star with prospects of a solid data return. Starshot’s Harry Atwater (Caltech) told the Interstellar Research Group in Montreal that it is about development and definition. Develop the physics, define and grow the design concepts, and nurture a scientific community. These are the necessary and current preliminaries.

Image: The cover image of a Starshot paper illustrating Harry Atwater’s “Materials Challenges for the Starshot Lightsail,” Nature Materials 17 (2018), 861-867.

We’re talking about what could be a decades-long effort here, one that has already achieved a singular advance in interstellar studies. I don’t have the current count on how many papers have been spawned by this effort, but we can contrast the ongoing work of Starshot’s technical teams with where interstellar studies was just 25 years ago, when few scientific conferences dealt with interstellar ideas and exoplanets were still a field in their infancy. In terms of bringing focus to the issue, Starshot is sui generis.

It is also an organic effort. Starshot will assess its development as it goes, and the more feasible its answers, the more it will grow. I think that learning more about sail possibilities will spawn renewed effort in other areas, and I see the recent growth of fusion rocketry concepts as a demonstration that our field is attaining critical mass not only in the research labs and academy but in commercial space ventures as well.

So let’s add to Atwater’s statement that Starshot is also a cultural phenomenon. Although its technical meetings are anything but media fodder, their quiet work keeps the idea of an interstellar crossing in the public mind as a kind of background musical riff. Yes, we’re thinking about this. We’ve got ideas and lab experiments that point to new directions. We’re learning things about lightsails and beaming we didn’t know before. And yes, it’s a big universe, with approximately one planet per star on average, and we’ve got one outstanding example of a habitable zone planet right next door.

So might Starshot’s proponents say to themselves, although I have no idea how many of those participating in the effort back out sometimes to see that broader picture (I suspect quite a few, based on those I know, but I can’t speak for everyone). But because Starshot has not sought the kind of publicity that our media-crazed age demands, I want to send you to Atwater’s video presentation at Montreal to get caught up on where things stand. I doubt we’re ever going to fly the mission Starshot originally conceived because of cost and sheer scale, but I’m only an outsider looking in. I do think that when the first interstellar mission flies, it will draw heavily on Starshot’s work. And this will be true no matter what final choices emerge as to propulsion.

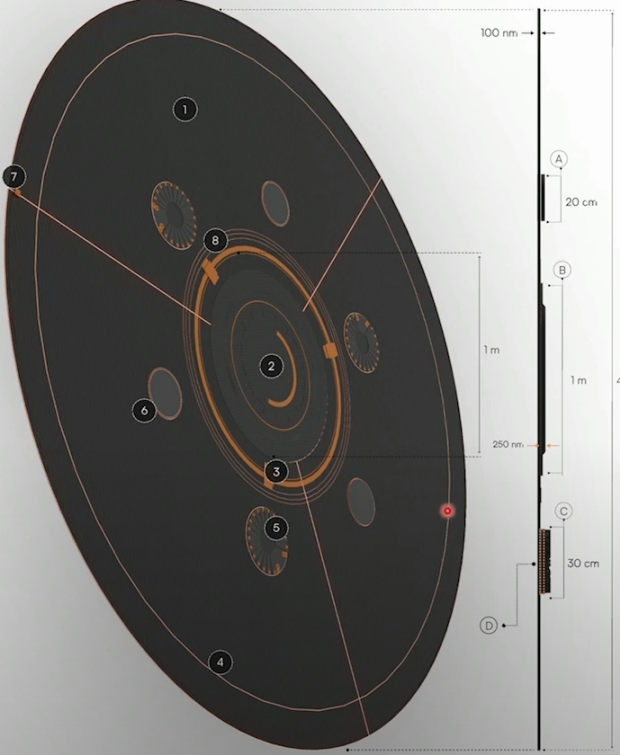

This is a highly technical talk compressed into an all too short 40 minutes, but let’s just go deep on one aspect of it, the discussion of the lightsail that would be accelerated to 20 percent of lightspeed for the interstellar crossing. Atwater’s charts are worth seeing, especially the background on what the sail team’s meetings have produced in terms of their work on sail materials and, especially, sail shape and stability. The sail is a structure approximately 4 meters in diameter, with a communications aperture 1 meter in size, as seen in the center of the image (2 on the figure). Surrounding it on the circular surface are image sensors (6) and thin-film radioisotope power cells (5).

Maneuvering LEDs (4) provide attitude control, and thin-film magnetometers (7) are in the central disk, with power and data buses (8) also illustrated. A key component: A laser reflector layer positioned between the instruments that are located on the lightsail and the lightsail itself, which is formed as a silicon nitride metagrating. As Atwater covers early in his presentation, the metagrating is crucial for attitude control and beam-riding, keeping the sail from slipping off the beam even though it is flat. The layering is crucial in protecting the sailcraft instrumentation during the acceleration stage, when it is fully illuminated by the laser from the ground.

How to design lensless transmitters and imaging apertures? Atwater said that lensless color camera and steerable phased array communication apertures are being prototyped in the laboratory now using phased arrays with electrooptic materials. Working one-dimensional devices have emerged in this early work for beam steering and electronic focusing of beams. The laser reflector layer offers the requisite high reflectivity at the laser wavelength being considered, using a hybrid design with silicon nitride and molybdenum disulfide to minimize absorption that would heat the sail.

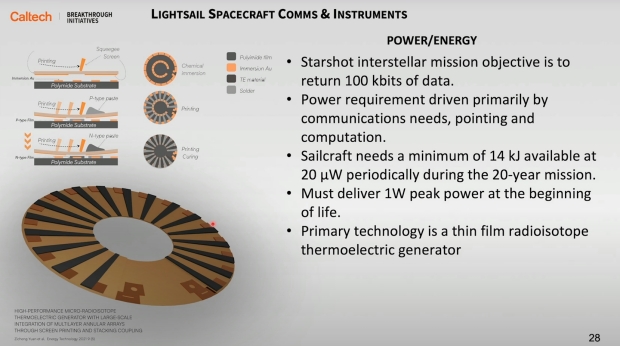

I won’t walk us through all of the Starshot design concepts at this kind of detail, but rather send you to Atwater’s presentation, which shows the beam-riding lightsail structure and its current laboratory iterations. The discussion of power sources is particularly interesting given the thin-film lightweight structures involved, and as shown in the image below, it involves radioisotope thermoelectric generators actually integrated into the sail surface. Thin film batteries and fuel cells were considered by Breakthrough’s power working group but rejected in favor of this RTG design.

So much is going on here in terms of the selection of sail materials and the analysis of its shape, but I’ll also send you to Atwater’s presentation with a recommendation to linger over his discussion of the photon engine, that vast installation needed to produce the beam that would make the interstellar mission happen. The concept in its entirety is breathtaking. The photon engine is currently envisioned as an array of 1,767,146 panels consisting of 706,858,400 individual tiles (Atwater dryly described this as “a large number of tiles”), producing the 200 gW output and covering 3 kilometers on the ground. The communications problem for data return is managed by scalable large-area ground receiver arrays, another area where Breakthrough is examining cost trends that within the decades contemplated for the project will drive component expenses sharply down. The project depends upon these economic outcomes.

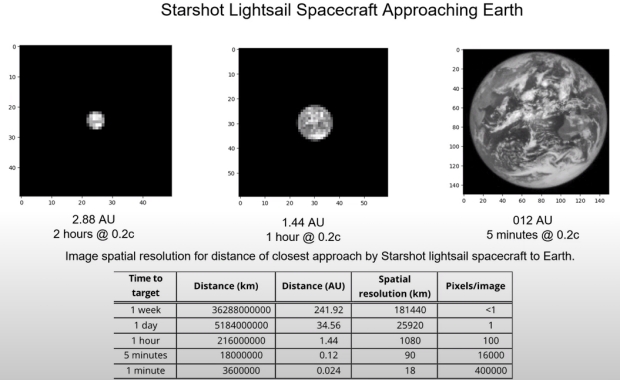

Image: What we would see if we had a Starshot-class sailcraft approaching the Earth, from the image at two hours away to within five minutes of its approach. Credit for this and the two earlier images: Harry Atwater/Breakthrough Starshot.

Using a laser-beamed sail technology to reach the nearest stars may be the fastest way to get images like those above. The prospect of studying a planet like Proxima b at this level of detail is enticing, but how far can we count on economic projections to bring costs down to the even remotely foreseeable range? We also have to factor in the possibility of getting still better images from a mission to the solar gravitational lens (much closer) of the kind currently being developed at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Economic feasibility is inescapably part of the Starshot project, and is clearly one of the fundamental issues it was designed to address. I return to my initial point. Identifying the principles involved and defining the best concepts to drive design both now and in the future is the work of a growing scientific community, which the Starshot effort continues to energize. That in itself is no small achievement.

It is, in fact, a key building block in the scientific edifice that will define the best options for achieving the interstellar dream. And while this is not the place to go into the complexities of scientific funding, suffice it to say that putting out the cash to enable these continuing studies is a catalytic gift to a field that has always struggled for traction both financial and philosophical. The Starshot initiative has a foundational role in defining the best technologies for interstellar flight that will lead one day to its realization.

In terms of progress, what stands out for me compared to the early ideas:

1. Sail beam-riding stability has changed from shaped reflective surfaces to a flat sail with material properties. This is a far more sophisticated approach and only requires the sail to be rotated to maintain stiffness and retain its shape. Metamaterials seem to be an exciting future in a number of domains.

2. Lasers and not microwaves to provide the power. The longer acceleration time over a longer distance would favor the lower dispersion of phased laser light.

3. IIRC, the original sail was to be 1 m in area with a total of sail and instrumentation mass of 1 g. The current design is larger and with more mass. Yet with thin film optics, we get lightweight cameras. [I wonder if thin-film lenses might even allow for a telescope design to improve imaging from further out from the target?]

4. The Use of LED light sources for steering. Early solar sail designs assumed steerable panels. Then JAXA’s IKAROS used LCD elements to change reflectivity to steer the sail. Starshot uses this latter idea but instead generates light to steer the sail. [I assume that these will be used to change the sail orientation during the cruise and then again as the sail nears its target].

5. The communication issue that seemed hard to solve initially now is “solved” using brute force with large numbers of inexpensive terrestrial telescopes.

@Michael. Note that they intend to have thin-film radioisotopes to provide power, with a peak of 1W at the target.

I am pleased that the end slide showed how different missions could be done as the cost of laser arrays declined, especially with the solar system and nearby interstellar space missions being achievable. Such an approach could launch many such sails to do some basic exploration and data collection, “pathfinding” more conventional missions with more instrumentation. Any interstellar intruder like ‘Oumuamua and Borisov could be targeted and imaged relatively easily at low cost. No more speculation on whether they are natural or designed artifacts.

In the Q&A, there was a question on astrobiology. One answer was that this technology might stimulate more work on miniaturizing instruments. While a little glib, it would be a significant benefit to find ways to extremely miniaturize instruments, which if they become extremely cheap, for wide use on Earth for monitoring stations. For example, doing in situ DNA/RNA/chemical analysis rather than local sample collection and subsequent lab analysis. This would be a path to mesh networks of “smart dust”.

Marry Starshot technology with the concept of using multiple star systems to decelerate, as well as Sirius as a booster, and we could have a number of probes traveling to the nearer stars and sending back data, or possibly even returning to the solar system. All happening within a few centuries from today, if we wish it.

I love your final paragraph, Alex, and have been planning to say more about Heller’s notions on boosting at Sirius. In any case, these are long time frames that currently seem inescapable, challenging our short-term cultural preoccupations. And they’re emphatically worth doing if we summon the will.

Swarming Proxima Centauri: Optical Communication Over Interstellar Distances.

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2309.07061

Good catch. I hadn’t seen this one yet, but do intend to cover it. Reminds me just a bit of JPL’s self-assembly concepts for the SGL mission, but applied in an entirely different way.

A very interesting approach – increasing the transmission power using a swarm. Assuming it will work, whether this approach or the Heller approach would be used, may depend on economics. The electrical cost of launching the swarm, plus the 1 km^2 ground receives vs. the single launch cost and the huge array of receivers from the author’s post.

What may tip the balance is whether the swarm can offer more than a large transmitter, perhaps doing more imaging or data collection during the cruise and at the target system.

It seems to me that this swarm concept can be tested within the solar system, both for launch using various means, the swarming of the units, communication, and data collection.

What a great way to do some basic data collection of the ice giants, improving on the flybys’ imaging back in 1986, 1989.

Fascinating paper! The central aspect of the swarm concept (phase-synchronized transmissions from all those probes) is still blurry, but there’s much more. They propose microlensing observations of Proxima b from low Earth orbit, discuss powerful betavoltaic cells using cheaper isotopes, notably Sr-90, and suggest illuminating the planet with the launch laser to do spectroscopy.

Yet I never lose the sense that Breakthrough Starshot is predominantly a military mission. Even if the most obvious applications of their launching lasers (nuclear defense) may be benign, the authors jest that each probe could be a “helluva flashbulb”, striking Proxima b with the force of “an old-fashioned ‘atomic’ bomb” (they do nobly suggest we should avoid targeting the planet if we’re able to discover intelligent life there before the flyby). The authors seem quite clever enough to work out something with a remote space mirror (like Forward’s) to project similar or weightier probes back at precise targets on Earth. The betavoltaic cells they propose to develop in ten years have diverse applications on Earth, but will they be nuclear-powered consumer gadgets, or ever-flying and ever-swimming spy drones that wait to punish ordinary people for leaving their permitted daily paths? And these distributed imaging and transmission capabilities seem well suited for embedding video surveillance throughout the landscape in ways that ensure there will be no hidden corner for Winston to hide from the telescreen. There is much appealing in this project, much hope, and for every part hope, a hundred parts fear.

Hi Paul

Marshall Eubanks, and the I4IS team, have a new paper discussing using swarms of sails, allowing greater data return. This isn’t a new concept – John Sisson’s “Dreams of Space” blog discusses the curious kids book “Beyond Mars” (1960) which features a discussion of a swarm of solar sails to probe Jupiter – different sails have different instruments and because they intercommunicate, they act as one much larger probe.

Yes, I just saw your tweet on that paper this morning and noted it for followup then. Had never heard of the Beyond Mars book. Curious indeed!