The question of infrastructure haunts the quest to achieve interstellar flight. I’ve always believed that we will develop deep space capabilities not only for research and commerce but also as a means of defense, ensuring that we will be able to change the trajectories of potentially dangerous objects. But consider the recent Breakthrough Starshot discussion. There I noted that we might balance the images we could receive through Starshot’s sails with those we could produce through telescopes at the Sun’s gravitational focus.

Without the infrastructure issue, it would be a simple thing to go with JPL’s Solar Gravitational Lens concept since the target, somewhere around 600 AU, is so much closer, and could produce perhaps even better imagery. But let’s consider Starshot’s huge photon engine in the Atacama desert not as a one-shot enabler for Proxima Centauri, but as a practical tool that, once built, will allow all kinds of fast missions within the Solar System. The financial outlay supports Oort Cloud exploration, fast access to the heliopause and nearby interstellar space, and planetary missions of all kinds. Add atmospheric braking and we can consider it as a supply chain as well.

Robert Freeland, who has labored mightily in the Project Icarus Firefly design, told the Interstellar Research Group’s recent meeting in Montreal about work he is doing within the context of the British Interplanetary Society’s BIS SPACE project, whose goal is to consider the economic drivers, resources, transportation issues and future population growth that would drive an interplanetary economy. That Solar System-wide infrastructure in turn feeds interstellar capabilities, as it generates new technologies that funnel into propulsion concepts. A case in point: In-space fusion.

To make our engines go, we need fuel, an obvious point and a telling one, since the kind of fusion Freeland has been studying for the Firefly design is limited by our current inability to extract enough Helium-3 to use aboard an interstellar craft. Firefly would use Z-pinch fusion – this is a way of confining plasma and compressing it. An electrical current fed into the plasma generates the magnetic fields that ‘pinch,’ or compress the plasma, creating the high temperatures and pressures that can produce fusion.

I was glad to see Freeland’s slides on the fusion fuel possibilities, a helpful refresher. The easiest fusion reactions, if anything about fusion can be called ‘easy,’ is that of deuterium with tritium, with the caveat that this reaction produces most of its energies in neutrons that cannot produce thrust. Whereas the reaction of deuterium with helium-3 releases primarily charged particles that can be shaped into thrust, which is why it was D/He3 fusion that was chosen by the Daedalus team for their gigantic starship design back in the 1970s. Along with that choice came the need to find the helium-3 to fuel the craft. The Daedalus team, ever imaginative, contemplated mining the atmospheres of the gas giants, where He3 can be found in abundance.

The lack of He-3 caused Icarus to choose a pure deuterium fuel (DD). Freeland ran through the problems with DD, noting the abundance of produced neutrons and the gamma rays that result from shielding these fast neutrons. The reaction also produces so-called bremsstrahlung radiation, which emerges in the form of x-rays. Thus the Firefly design stripped down what would otherwise be a significant portion of its mass in shielding by going to what Freeland calls ‘distance shielding,’ meaning minimal structure that allows the radiation to escape into space.

A starship using deuterium and helium-3 minimizes the neutron radiation, so the question becomes, when do we close the gap in our space capabilities to the point that we can extract helium-3 in the quantities needed from planets like Uranus? I see BIS SPACE as seeking to probe what the Daedalus team described as a Solar System-wide economy, and to put some numbers to the question of when this capability would evolve. The question is given point in terms of interstellar probes because while Firefly had been conceived as a starship that could launch before 2100, it seemed likely that helium-3 simply wouldn’t be available in sufficient quantities. So when would it be?

To create an infrastructure off-planet, we’ll need human migration outward, beginning most likely with orbital habitats not far from Earth – think of the orbital environments conceived by Gerard O’Neill, with their access to the abundant resources of the inner system. Freeland imagines future population growth moving further out over the course of the next 20,000 years until the Solar System is fully exploited. In four waves of expansion, he sees the era of chemical and ion rocketry, and perhaps beamed propulsion, to about 2050, with the second generation largely using fission-powered craft, in a phase ending in about 2200. 2200 to 2500 taps fusion energies (DD), while the entire Solar System is populated after 2500, with mining of the gas giants possible.

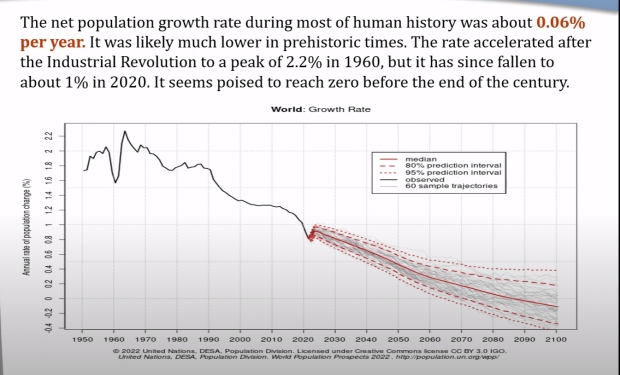

Let’s pause for a moment on the human population’s growth, because the trends noted in the image below, although widely circulated, seem not to be widely known. We’re looking here at the growth rate of our species and its acceleration followed by its long decline. As Freeland pointed out, the UN expects world population to peak at between 10 and 12 billion perhaps before the end of this century. After that, increase in the population is by no means assured. So much for the scenario that we have to go off-planet because we will simply overwhelm resources here with our numbers.

Image: In both this and the image below I am drawing from Freeland’s slides.

You would think this Malthusian notion would have long ago been discredited, but it is surprisingly robust. Even so, orbital habitats near Earth can potentially re-create basic Earth-like conditions while exploiting material resources in great abundance and solar power, with easy access to space for moving the wave of innovation further out. BIS SPACE looks with renewed interest at these O’Neill habitats in its first wave of papers.

The larger scenario plays out as follows: In the second half of our century, we move development largely to high Earth orbit, with materials drawn mostly from the Moon, using transport of goods by nuclear-powered cargo ships. The third generation creates orbital habitats at all the inner planets (and Ceres) and perhaps near-Earth asteroids using DD fusion propulsion, while the fourth generation takes in the outer planets and their moons. At this point we can set up the kind of aerostat mining rigs in the upper gas giant atmospheres that would enable the collection of helium-3. Here again we have to make comparisons with other technologies. Where will beamed spacecraft capabilities be by the time we are actively mining He-3 in the outer Solar System?

I’ve simplified the details on expansion greatly, and send you to Freeland’s slides for the details. But I want to circle back to Firefly. Using DD fusion, Firefly’s radiator and coolant requirements are extreme (480 tonnes of beryllium coolant!) But move to the deuterium/helium-3 reaction and you drop radiation output by 75 percent while increasing exhaust velocity. Beryllium can be replaced with less expensive aluminum and the physical size of the vessel is greatly reduced. This version of Firefly gets to Alpha Centauri in the same time using 1/5th the fuel and 1/12th the coolant.

In other words, the sooner we can build the infrastructure allowing us to mine the critical helium-3, the sooner we can drop the costs of interstellar missions and expand their capabilities using fusion engines. If such a scenario plays out, it will be fascinating to see how the population growth curves for the entire Solar System track given access to abundant new resources and the technologies to exploit them. If we can imagine a Solar System-wide human population in the range of 100 billion, we can also imagine the growth of new propulsion concepts to power colonization outside the system.

As a title, “Infrastructure and the Interstellar Probe” strikes me as a surface description of an iceberg, the depths of which follow in the text. What to do with the dilemma of sending a small interstellar probe or a large telescope – and how do you engender it with a space based infrastructure – or not – since the global based infra-structure appears very much in jeopardy – the space based presumably an extension of that down here on Earth might be under serious duress too.

The earth based threat has been lurking in the background, as far as I could tell, since about the International Geophysical Year and articles I could read about then in the grade school “Weekly Reader”. It didn’t say Malthus, but with doubling populations, you got the idea. Yet at about that time space based infrastructure was given birth: either with plans for satellites to commemorate that “geophysical” year – or the actual launch of Sputnik. So perhaps we are still moving down that paradoxical path. Maybe as we go more wisely and with less damage.

But on a narrower scale, there is still the dilemma of “scopes” vs.” space probes” to the stars, even more immediate than that old saw about starships launched too early would be met at their destinations by starships launched later ( And one should hope!).

For the present time, I have to wonder if a star shot could give us as much information about a star system with planets as a successor to JWST or Nancy Roman Space Telescope built in compliance with a payload container based on a Starship heavy launcher. One could still have a folding main mirror, but have larger hexagonal cells. Or a less complex telescope could be dispatched to a Lagrangian point and join a phased array of similar inexpensive models, assuming Starship heavy launchers deploy faster and cheaper than Artemis like craft.

Assuming we do exploit a gravity lens focal point 550 AUs or so away, we still haven’t decided on or detected which stellar system we want to concentrate on.

An awful possibility is dedication to an early candidate and discover a more interesting target pointed through the sun in another quadrant of the celestial sphere. And that poses a cost effectiveness problem for star shots too.

Consequently, I think there is much to argue for continued development of more survey devices: the successors of Gaia, NRST(?), JWST and others. And even if they largely do detailed galactic census work, let’s say they do discover that a Trappist-1 d or f is paydirt, what then? There is still a possibility that a dedicated instrument in space can tell us more about what we want to know than a cigarette pack sized space probe shot toward it in decades long transit as a fly by.

Space infrastructure, I suspect, will continue to grow on the basis of a wide range of economic, industrial, scientific and cultural reasons. If we can eventually inhabit any of the local real estate – such as Mars, some portion of the GDP of such a realm will be devoted to further expansion. And the immediate problems of lunar or martian aridness might very well be addressed by diverting volatile materials in deeper space toward their surfaces or low orbit. Of course, many of the developments described likely lead to further breakthroughs and could critical enough for a pivot. Yet getting liquid out of those pipelines to Mars and Moon will take a while, but likely flow faster and in the more immediate future than fixed target interstellar expansion based on how spacecraft ( Pioneer, Explorer, Discoverer) surveyed the solar system in the 1960s.

‘And the immediate problems of lunar or martian aridness might very well be addressed by diverting volatile materials in deeper space toward their surfaces or low orbit.’

For the moon we could build a powerful enough magnetic field pretty much any where on the surface to funnel hydrogen to the surface to form water.

SLS is cheap compared to all the Helium 3 handwaving.

Block 2 SLS with NTR upper stage and NEP probe…that’s your interstellar probe.

Show some BoE calculations. AFAICT, your “interstellar probe” would still crawl.

NYT article warns of population collapse after a peak later this century. Of course there must be all sorts of assumptions.

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/09/18/opinion/human-population-global-growth.html?unlocked_article_code=jWDhVueRX1Icqi_CnqJL-37NQjp7jAKsEdq-eruZiSdAkULOg8fNRXAe8tGV1zaFnYpcoGzE38kwr9W_dI6zeI5oYqJaexWmK9N8TqCfWS0dhFjhkcLdE6LY1Kx2SiwdLIBSJtkjLsLtnkCvjgC35fJkbhWU7_KmCRTZSxeWYdfiOUrpAhF8BPOPeZn7U6ad3Swl0Rfln1G70Z8bMaKo10jhbUdyxtdVU6zTIbkUdcmaMYUUrR4qZ1KYQ6KdfsxHQaBXutVPpvV-BCq8ombnd7PnfRGfcH2GB5394vm-de2BYAlPlOkBc43BF_m25imz_UMyYt8JgZvYDskBO6fP5ThGSP2Mzc57ShbvpG1NscYzK5Vprz0DcEo&smid=url-share

The transformation from an Earth-bound civilization to a solar system-wide human civilization seems to be absolutely essential if we or our descendants hope to engage in interstellar exploration or expansion, I expect or hope that the interplanetary socio-economic infrastructure would provide the support for such a technically difficult and economically costly endeavor such as interstellar exploration, In ways which I can only speculate. human will exploit the resources of the inner and outer planets/asteroids/moons, etc. to support our future interplanetary civilization. However, it seems to me that we will need develop breakthroughs in more reliable fuel sources (fusion the power source of the future) which are faster and “way more” economically efficient and breakthroughs in space medicine in order for that spacefaring vision to come into fruition . Of course, I am pulling for advancements in space flight & space medicine to advance the human footprint in addition to the robotic presence in the solar system. two final thoughts. The UN and the US Census world population projections indicate that Africa is the only continent which actually has a high rate of population increase. On average, the G7/8/9 countries -China, Japan, Russia, Italy, Germany, Sweden ,etc – are projected to LOSE population over the course of 25 years or less. USA, UK, France, and Canada etc. population increases are due to the migration from high birthrate countries in Central America, South Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, Haiti, etc. I think that it is highly unlikely that there will be 100 billion future human inhabitants living throughout the solar system in the next one or two hundred years.

The idea that the solar system could have a population of 100 bn after 20,000 years is unlikely to be reasonable. I think John Lewis suggested that the resources of the solar system could support trillions! While our human population has taken around 15000 years to reach the current numbers since the transition from hunting to farming, the huge growth we experienced has happened since the Industrial Revolution. Our economy almost has to keep growing fairly rapidly to maintain our “liberal-democratic” techno-economic culture. Even at modest rates of economic growth, within a few thousand years we would be K2 civilization, and then growth would stagnate. Whether we could maintain a hi-tech civilization under those conditions I am skeptical. IMO, more likely it would be like Europe after the fall of the Roman Empire – a decline in capabilities that took hundreds of years to recover. China likes to say it has had a continuous civilization for thousands of years, but its economic growth was static during much of that time. China’s current high rate of growth is unsustainable and would have to become almost zero growth within a few decades.

What would a hi-tech population spread around the solar system look like if economic growth was extremely low, like that of all cultures before the Industrial Revolution? Most likely it would revert to earlier forms of governance which would not be desirable to many of the current nations.

To build starships and expand into the galaxy, we need a growing economy that can lavish some output to this project. This suggests that this will have to be accomplished within the next few thousand years at the latest.

The only obvious way out is for habitats to become worldships while low-fraction of c STL travel is achievable and start the journey to the stars well before the solar system civilization becomes a K2. It, in turn, will be a zero-growth environment. Whether it can be sustained over the millennia it would take to reach another star system, IDK. The various scifi novels depicting these journeys seem too optimistic about the survival of these ships and their “crew”. However, any successful journey could found a new seed population around another star.

Unless there is another path to take, it seems to me that our type of civilization can only flower for a very brief cosmic moment. Either we succeed in reaching the stars in that time, or we will forced back into a lower-tech civilization, possibly only surviving on Earth. Stephen Baxter’s “Evolution” is even more depressing. Humanity eventually becomes a tiny population of small primates living symbiotically with a tree.

As Oswald Cabal says at the end of the movie “Things to Come”: “…all the Universe or nothingness!”

In summary, solar system populations of 100bn+ that reach that level after 10s of millennia is fantasy simply because our civilization is dependent on economic growth which will run out of energy growth within a few thousand years. We are already struggling with low single-digit economic growth. Can our civilization even survive when growth falls below 1% pa?

I am encouraged that reaching the stars just possibly may be nearer than previously thought. Whether our biological or post-biological descendants will be the explorers, IDK. But as Clarke indicated in his Odyssey novels, “mind” was the most precious thing in the universe. If we can spread our intelligence across the stars, that would be a worthy result.

Wouldn’t Deuterium-He3 fusion have the same Brehmsstrahlung issue? It’s not just the heating from the x-rays – it bleeds power out of your reactor, so that it becomes much harder to get net positive power.

Until we have meaningful medical immortality, that’s probably the best “pull” factor for these colonies – “much vaster personal space” inside a habitat with the weather and conditions you want.

Meaningful medical immortality would be catastrophic for the Earth even with a small amount of outward expansion such as space colonies, Mars, and some outer moons. Thing of the consumption levels of hundreds of millions or billions of “immortals”. We can’t even take care of Earth now with lifespans of 100 years or less and dwindling population growth (0.88% as of 2022). Take a look at the climate caused problems occurring around the Earth with our massive negligence. Canada alone will generate more than 600 million tons of CO2 from forest fires only! The global total from forest fires will be about 1.7 Gigatons added to the current rate of 37 Gigatons of CO2 annually. Total disaster. We are above the 420 ppm redline now and climbing fast. Runaway greenhouse effects are beginning. Forget about thousands more years of human civilization. Focus on the next 50 or less. That’s what we have to clean up our act literally.

“Total disaster.”

Riding the Climate Toboggan

Lots of strawman arguments and disinformation in that blog post. But it is too OT to warrant discussion.

Gary, we have had higher temps in the past. I think we have triggered a rapid rise in global temp that would have happened anyway. I would think the fall in temp would be far worse -8 or -9 is extremely dangerous. Just wondering if the warming Temps create an environmental conditions for massive plankon blooms that cause a massive absorbtion of CO2 that causes the rapid falls in temperature.

Science first panic second…

You are completely ignoring all the climate data that has been published over the last few decades Michael. This is the result of mankind ignoring a massive problem for decades. I am not panicking, I am pointing out the truth, which so many have and continue to ignore. We are deep into the consequences now. Please read some climate science. A massive population correction is coming, meaning hundreds of millions if not billions will die. That is a terrible way to help solve a crisis. Denial will not prevent what is coming. Denial did not prevent what has already happened. Lying politicians will not solve the crisis. We need immediate drastic action. Your country will undergo extreme climate change that will reduce your GDP and destroy millions of lives. These are facts. They are now inescapable. Saying science will solve everything is nonsense since we are unwilling to put enough money behind it and we are coming to the problem decades late. We need to not only flatten the CO2 emissions curve we need a drastic downturn. The consequences of our foolish actions are already in the atmosphere now. The amount of heat produced per square meter of the Earth’s surface has more than doubled in the last twenty years alone. Can you imagine the climate consequence of that? Well you don’t have to imagine it, because the consequences are already here.

Gary Wilson, it sounds like Michael is fully aware that global warming is occurring. Instead, they are arguing that because the Earth was warmer millions of years ago, when there was no complex global food and water infrastructure keeping 7-8 billion humans alive, current warming will not threaten our food and water infrastructure. This is an obviously ridiculous argument that uses the general Earth’s survival as a straw-man to distract from millions of dead humans and wrecked ecosystems. Global warming deniers have mostly moved past the denial stage and are now in the who cares stage.

I am not convinced that reducing the population will effect the long term legacy of global warming. Halve the population and we are at 1970 levels. We were still contributing to global warming and a population in crisis is unlikely to be able to decarbonize. The time to decarbonize is now, when we are economically strong.

I totally agree Harold. We must de-carbonize now. We can afford it and it will do the most good if we do it now. Waiting further would be disastrous. It would be akin to what we’ve been doing for the last 30 years. Put it off and put it off and talk some more but do nothing and point fingers at other emitters and so on and so on ad nauseum. If you’ve seen How to Boil a Frog you know what humans do. They aren’t designed evolutionarily for long term (not so long term now though) problems. Put it off for another generation. Politicians who know they will be long gone from office when things really, really get bad. Take note Justin Trudeau.

It’s certainly not the hottest it’s been, yes we should start to decarbonise but I don’t think we should go balls out on it. CO2 can be a very useful compound if we recycle it.

https://www.climate.gov/news-features/climate-qa/whats-hottest-earths-ever-been

Michael. If there were a high enough demand for CO2, carbon sequestration wouldn’t be such an economic challenge. We would expect it to be already happening. I am not sure what you mean by “balls out” but please do not factor the assumption that anyone wants to remove all CO2 from the atmosphere into your own response to global warming. Personally, I am all-in on preventing future glaciation events.

As a people, we depend on a climate that supports wide open plains for most of our food. Please think hard on whether we could be as populous on a tropical planet. I am not convinced Earth’s more common climate suits human civilization.

Harry, there are many processes for converting CO2 into plastics.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/351148449_Capture_and_Reuse_of_Carbon_Dioxide_CO2_for_a_Plastics_Circular_Economy_A_Review

As for balls out I mean governments doing anything to enforce the decarbonisation i.e. Dictatoral and potentially financially enslaving their populace.

Michael, The processes described in the paper will make plastic more expensive. Without government mandates and tax payer funding, there is no economic logic behind the assumption that we can mitigate the continued burning of fossil fuels by removing CO2 from the atmosphere to make more expensive versions of existing products.

Global warming is happening and someone will be forced to pay, forced to adapt.

Harold, it’s going to be expensive anyway, you bet on it ! The CO2 could come from carbon neutral sources there by removing the fossil fuel component.

Uses of CO2 Uses are less than 1% of annual CO2 emissions. I cannot see that ramping up that much to offset emissions.

CO2 capture from the air is very expensive. It is best done at fossil power plants where the emissions are much richer in CO2.

We have seen how industry has used the economic cost argument to delay phasing out fossil fuels. Making anything much more expensive to manufacture is difficult. Just look at the way H2 production is still currently done using carbon fuels, especially CH4, rather than the more expensive “green hydrogen”.

Yes, the planet has been hotter than it is now. However, humans are not adapted to these hotter temperatures. There are already parts of the populated world that are experiencing temperatures that are at the limit of human tolerance. As the globe heats further, a number of regions will become uninhabitable by humans without technological support, like A/C. And what about the animals outside?

The second issue is food production. As the climate gets hotter and the weather more variable, crop yields fall. The facile answer of is that crop production will move north (in the Northern hemisphere). However, that will not work because the current permafrost areas and bare rock exposed by melted glaciers will not support the crops we grow currently.

Then there is the issue of tropical diseases migrating into the temperate regions. Western healthcare has largely ignored these diseases as they are not considered profitable. How many people will be injured or die before we get any treatments for these diseases given the 15+ years for a candidate treatment to reach the clinic?

Lastly, and another big one, is sea level rise. You may have read that there are attempts to protect areas around coastal cities in the rich world. The expense to do so is huge, and will only protect select some parts of the coastline – usually starting with the wealthier areas. (Disaster capitalism is operating too, buying up land from owners Florida, Alabama, and Mississippi are so low-lying that they will face similar problems to low-lying Pacific islands that are disappearing below the ocean surface. Poorer parts of the world will see events like the flooding in Derna, Libya. All these climate effects will drive refugees north. What then? The “sensible” approach would be to move populations to higher ground, but that means abandoning the accumulated infrastructure of urban dwellers and transport hubs, like ports.

The reality is that mitigation is vastly more expensive than not smoking this worse. Unlike prior civilizations, we have knowledge and technology. Sadly, like prior civilizations that collapsed through inaction, we are experiencing the same inaction, probably with similar excuses.

Some have suggested we really should be on the equivalent of a war footing to meet the needed changes. As the crisis worsens, they may increasingly prove correct.

These blooms seem to be occurring more often, perhaps we could us the blooms to remove more CO2.

https://www.cbc.ca/news/science/phytoplankton-blooms-grow-climate-change-1.6764789

The algal blooms only permanently absorb CO2 if the cells die and fall to the seabed and are sequestered rather than consumed. There is very little evidence that happens. What we do know happens is that algal bloom die off results in deoxygenated waters killing animal life. Then there are the toxic red algae blooms that directly kill animal life.

The experiments adding the micronutrient iron to the seas have had mixed results. Where the ocean currents maintain oxygenation, algal blooms can increase fish yields. Where they are not, such as in the Gulf of Mexico, agricultural fertilizer runoff ends up in anoxic waters, destroying the fishing industry.

And we doing these experiments because [the global] we will not phase out carbon fossil fuels fast enough.

I did read Kim Stanley Robinson’s ‘The Ministry for the Future’ last month. Partly a novel, partly a monograph on climate change. I was mostly interested in the the novel’s social solutions rather than the geo-engineering solutions. For example, the minting of a ‘carbon coin’ mined through CO2 sequestration and the adoption of a personal data privacy ‘YourLock’ account that allows people to manage their own digital DNA. These actually exist in reality if in an early form: the KLIA coin and Inrupt SOLID Protocol.

‘Catastrophic’ medical immortality might not be so catastrophic if it engenders a mindset that accepts responsibility for the long-term consequence of actions (that one is likely to personally encounter) in contrast to a mindset that continually rationalises ‘I’ll be long dead before that ever happens…’

I think space infrastructure belongs in space rather than on earth. Seems like lasers on the ‘dark’ side of the moon – or even atop the pole – would ultimately be easier to train on a target sail that on an equatorial mountain top spinning at 1000 mph.

“Oye, Beltalowda. Listen up. This is your Captain, and this is your ship. This is your moment. You might think that you’re scared, but you’re not. That isn’t fear. That’s your sharpness. That’s your power. We are Belters. Nothing in the void is foreign to us. The place we go is the place we belong. This is no different. No one has more right to this, none more prepared. Inyalowda go through the Ring, call it their own, but a Belter opened it. We are the Belt. We are strong, we are sharp, and we don’t feel fear. This moment belong to us. For Beltalowda! Beltalowda! Beltalowda!”

Medical immortality really isn’t a Malthusian threat. Exponential growth, even at under 1% a year, still happens at the nursery. More importantly, either medical immortality will not deter war, in which case it is nearly meaningless, or it will, in which case the whole vast terrible cost of combat will be avoided by wise or cowardly old people. On the other hand, the fear of death is the beginning of slavery, and in the world people make without war, some might have reason to wish we had accomplished global extinction after all. People aren’t predictable, and societies aren’t predictable; the very essence of sentience is that there is no telling what could happen. In the meanwhile, let’s not hasten to volunteer our parents to the recycling vats – neither literally, nor more effectively by strangling research in its cradle.

Though renewable energy has been amazing so far, I suspect our best CO2 technology may yet come from the original people of Amazonia, who invented the art of terra preta. Farming with cheap desalinated water and a mix of poor soil and biochar from the fields, it should be possible to sequester unlimited amounts of carbon as a means of increasing global agricultural production.

This may help on possible fusion gain.

https://nickhawker.com/

The phased array laser could be used to send power to the moon and literally resurface it for solar cells to be printed onto its surface. Its this integrated ‘paying’ approach that will drive our outward expansion. The power of the laser array would allow us to move light weight sail satellites directly from the earth into space by say having a donut balloon with a lens and mirror component in the centre to recycle laser light to do the job.

I would love to see one of these MHD’s generate the power, 250 million watts per cubic meter with around 65% in a combined power unit !

https://www.britannica.com/technology/magnetohydrodynamic-power-generator

Two words are missing: advertizing and consumerism. Thanks to advertising, people will continue to shop passionately. If ads did not increase sales, then companies would stop advertising and save money. Ads stress enjoyment, immediate satisfaction, and instant gratification. People without money hear and view such ads, and then they feel even more stressed out. Raising a child entails years of sacrifice, a word that is absent from commercials. Sacrifice and self-control cannot be reconciled with consumerism.

People hear: “You deserve this. You are worth it. Enjoy!” They hear “you, your, you” and think “I, me, mine” instead of my family, my children, my grandchildren, my country. Below replacement fertility is a fact of rich societies around the world, regardless of race, religion or political system.

Maybe 2.5 billion people 250 years from now is more realistic than 25 or 100 billion.

If consumerism could reduce the world population to 2.5 bn, a number close to that when I was born, that might be an acceptable tradeoff and therefore a good thing. It would certainly take the pressure off food production, biodiversity loss, and carbon emissions.

However, I recall what living was like in the middle of the last century and I really do not want to go back to that “different country”. Go back another 3 centuries and the global population was less than 1 billion, with most people living impoverished lives, high child mortality, and starvation always a poor harvest away.

The declining population of the native-born in the rich nations is due as much to unequal income distribution as consumerism. [To be clear, I am not advocating poverty as a means to reduce populations in rich countries.]

Now if Thanos would drop by and cut the global population by 1/2, this would likely have similar, positive, societal effects as the Black Death in Europe. But this is too much like “aliens will save us”. We really need to find our own solutions to what is starting to look like a Great Filter ahead of us, and if Sir Martin Rees’ prognostications are on the mark, just one of several Great Filters that could end our species’ current technological civilization.

The demand for a large population disappears if we assume robots can duplicate the labor of humans and that these robots can build more such robots. A lot of what is required for building infrastructure is basic labor which we should be confident can be robotized. It is also becoming apparent that creative problem-solving can be “robotized”. Why would a population of 100 billion be necessary if 1 person can do the work of 1 billion? There is good reason why many look at the development of robotics, machine learning, and Ai and question if there is a place for themselves.

The best explanation I’ve encountered for slowing population growth in developed countries is the ever increasing cost to maintain an ever expanding lifestyle. As lifestyles grow in complexity and size, the carrying capacity of an environment drops. You can fit more insects in a given area than elephants. We have no evidence that evolution selects for small lifestyles and high carrying capacities. I am unconvinced that humanity or any other space faring people will select for high carrying capacity over lifestyle size and complexity.

And we know what happened to horses after the invention of ICE powered transport. How do we manage any such transition without the equivalent of knocker’s yards? OTOH, I could imagine living in the equivalent of a Spacer world like Aurora or Solaria with a retinue of robots. Asimov’s solution for Earth was no robots, but people living highly controlled lives in small spaces. I doubt we will prevent robots operating on Earth, so the problem of not obsoleting billions of humans remains.

We’re all here on this site because we share a desire to explore the universe.

But, historically, as a species, have we been predominantly explorers or instead destroyers of worlds?

We’re on pace to destroy just about every unique ecosystem on this planet — along with multiple unique “worlds” of prior human cultures, such as the indigenous cultures of the Americas and pre-Perry Japan — for an in truth globally homogenous corporate urban sprawl – with the ultimate fate of the overall planetary ecosystem further in serious question.

And folks want to take that long history of rapacious behaviour out into the solar system, to, e.g., ablate the surface of the Moon, terraform planets, etc., etc. Destroying unique environs that have taken billions of years to manifest themselves.

All to create a solar system wide infrastructure with 100 billion humans in order to carry that rapacious behaviour even further out into the cosmos.

That’s perhaps not exploring with wonder at this vast universe. It instead tends toward manipulating to the point of functional elimination virtually every environ that science, technology and engineering give us the capacity to get our rapacious little homo sapiens hands on.

I believe that we need to seriously look at the fundamental ethics of how we plan to interact with the cosmos, assuming that we survive in the first instance. Just because science, technology and engineering enables us to do something doesn’t mean that we have to do it that way or should do it that way.

Maybe the answer to the Fermi Paradox is that, yeah, they know we’re here, but they don’t want to have anything to do with us because we’re little [expletive deleted by author] that screw up just about everything that we get our hands on.

I mean, I like people, a lot of people. But I’m not sure that, on balance, as a species, the nine billion homo sapiens on this planet collectively are behaving in such a manner that it necessarily would be a great thing to increase that particular species 11-fold and spread the species out all over the solar system and beyond.

So let’s explore, that solar system and beyond. But I believe that we should do it with wonder and awe – and at the very least give the exploratory side of science a chance to wonder and marvel at the unique environments that we encounter before we “pave the universe and put up a parking lot,” to paraphrase Joni Mitchell.

Perhaps, just perhaps, we can find a way to send a probe to Proxima Centauri without first metaphorically paving the solar system with enough spaces to accommodate 100 billion.

With time, science ultimately should enable us to do just about anything that we envision. But our vision should drive the science, not vice versa.

Cue “They paved paradise, And put up a parking lot” – Joni Mitchell. Lyrics to Big Yellow Taxi

I’m in two minds about this. Evolution also changes things, albeit over far longer time frames. The oxygenic photosynthesizers poisoned the environment with O2, but that in turn gave rise to a greater diversity of forms. In the oceans, algae remain the dominant plants, whether unicellular or multicellular. But on the land, they have evolved many forms. Until the Cretaceous, there were no flowering plants, but now they are ubiquitous and have co-evolved pollinators. With sufficient rainfall, the last level of succession is the forest, whether tropical or boreal. Yet animals ensure that meadows can exist and this patchwork of environments maintains a higher biodiversity.

Humans have unarguably changed the landscape, even before the Industrial Revolution. Ancient cities like Athens and Rome were quite unpleasant places to live, but far more attractive than the countryside. The same thing is true today, as urban populations now exceed 50% of the global population. Megacities develop for the same reason as cities have always attracted people.

What has happened is that the idea of growth has become a runaway success. Our system is not that different from Bostrom’s “Paperclip Maximizer” thought experiment for rogue AIs. Corporations are profit maximizers, which in Western terms means growth maximization.

We are constantly running against a return of the Malthusian Trap – which requires consuming more natural resources for food and goods production.

The question is whether this harm to the existing natural environment is truly bad, or whether it will spawn a new period of evolution, perhaps more in terms of ideas rather than just life forms. Just as O2 photosynthesizers pushed anaerobes into niche habitats, our activities will push the existing life forms into refuges, probably with vastly decreased biodiversity. But our age is also spawning new things, which may be more valuable in cosmic terms than our biological past.

I would certainly prefer Earth to be a refuge for life. If that means paving over rocky planets, building space habitats/cities, and dismantling giant planets to increase our numbers and the diversity of thought, knowledge, and new ways of living and even being, then that might well be a worthy outcome.

Some of the wanton destruction on Earth is indeed reprehensible. Rapaciousness is a net negative even when claimed to be justified (but ultimately it is just for short term “profit”). We may “… don’t know what you’ve got, Till it’s gone”, but if we get through the various crises ahead, there is an argument that we will have benefitted the universe. I hope we can do that without completely destroying everything, even if we do end up building museums, not for trees, but for planets.

Well, Alex, we’re back to that very good discussion of whither from here.

I guess in the Grand Scale of Things, over the aeons, it indeed is Life that is the destroyer of life, as prior ecosystems and life periodically are destroyed by succeeding ecosystems and life that live and flourish via the very precipitating changes that constitute an apocalypse for their predecessors.

Shiva always was such a deep intuition into the nature of the Universe, being both destroyer and creator in one.

Although, as a contrast, I’m hard pressed to identify, at least as yet, any Cambrian-esque explosion of myriad new life forms that we are precipitating. So far, we instead are generating a comparative implosion tending to reduce biodiversity to basically one dominant species living in one predominant ecosystem, perhaps with a proliferation of certain preexisting but similarly opportunistic species like pond scum.

Another difference between us and the ultimate Cambrian explosion, perhaps, is that we have at least the delusion of free will. We ostensibly can choose – envision – a different path than we heretofore have taken, and currently are on.

And while it is somewhat easy for highly intellectualized people to view ideas as a form of evolution potentially transcending life itself (I was a philosophy major for the first three years, so I get it), I guess it’s the more poetic side of me that finds transcendence and revitalization instead in, or at least also in, nature. You even may have found that Greek countryside in the 5th Century B.C., and the countryside environs that still remain in the world today, not quite as bad as you think. If the urban environment is the pinnacle of human existence, then, well . . . we might want to rethink that one. (Reminds me of a sci fi story I read back in that library in Danvers, Massachusetts, with the long shadows stretching across the wood floor from the winter sun coming through the windowpanes, where virtually the entire human population was packed into these tall superskyscrapers.) Having all the newest “mod cons” as my Welsh ex from Caergwrle used to call them, is not necessarily all it’s cracked up to be, as a way of . . . life.

I would imagine that there were writers several hundred years ago that similarly imagined an idyllic post-Colombian European landscape facilitated by the resources and, in all of its forms including some very ugly, offshored cheap labor of the New World. That life certainly was realized by some Europeans, read more accurately as a precious few living on massive park-like estates isolated and insulated from the Europe experienced by the rest.

Perhaps Earth indeed could be transformed into a park-like world enjoyed by at least some, likely those elites that ultimately game any system to their advantage, as we’ve discussed before. With the necessary production, etc. being accomplished in the new Off-World, hopefully without the scourge of actual – or practical – slavery this time.

I tend to suspect, however, that the likely result perhaps instead might be more akin to Philip K. Dick’s Blade Runner universe (at least as portrayed in the movies). Our capacity for living the dystopias imagined by writers seems to be unbounded – as we race toward a Brave New World zealously embraced by billions nonchalantly giving up fundamental privacy and, ultimately, as they are inherently paired, freedom, just to get the triviality of the most recent streaming video experience.

To me, rapacious behaviour is rapacious behaviour, whether practiced by, inter alia, white Europeans in past centuries leading to the present day, or instead by intellectuals of instead varied ethnicities pursuing a purported utopia of ideas to the detriment of the sometimes stark beauty that lies before them.

Intellect and Nature are at odds only if Intellect so chooses. And I do believe that we have that choice, to coexist rather than destroy.

So, for me, it remains a fundamentally ethical question – of both how we want to be and how we want to interact with the cosmos, both the part that we currently are on as well as the rest, as we begin our journey out into the stars.

I agree that we should assume a world that is, not as we would like it to be. Heinlein wrote his SciFi stories on that basis which tended to be rather different from the more techno-utopian ideas of others.

I was hopeful that the environmental destruction that was so evident by the 160s would reverse with the Environmental Movement of the 1970s. It did see that things were getting better again – until the Friedmanite gospel of investment returns are paramount came to dominate the business of the Anglophone world. Then things started to get worse again.

As @Project Studio notes, we may end up with a Solar System culture as depicted in the Expanse. Gritty and unfree. It would not surprise me in the least if indentured servitude is offered to the wannabe Mars colonists. Slavery in all but name.

In any age, humans should want to preserve the species that we live with. If we cannot, a genetic library should be built like the Svalbard Seed Vault with the hope that eventually our technology could successfully resurrect species and ecosystems. If we could ever travel back in time, I would try to do that for as many species as have ever lived on Earth.

But should we migrate into space, I am certainly not averse to putting “parking lots” on other planets. We just need to develop some regulations to keep this under control. Islands like Maui have been severely over-developed since I first traveled there. Bermuda is another island that has been overdeveloped IMO, and arguably was when I lived there in the late 1980s compared to what it was like in the after WWII. Floating cities on Venus and Saturn are fine, as long as they are not so dense as to feel like a global parking lot. Even a Dyson swarm might be too dense for comfort if we aim to become a K2 civilization. Perhaps that will drive interstellar migration.

Without the emergence of human-level intelligence and technology, life on billions of planets would cycle through their evolutionary cycles, periodically set back by disasters, possibly even permanently. Only mind has the power to transcend this and offer new things in the universe. We can seed sterile worlds, create new lifeforms, and create wonders. We even may be the first in our galaxy to be able to do this. We do have the power to create a just civilization, even if the social dynamics keep trying to recreate rule by the individual. We are the result of our primate evolution and have to keep fighting to steer away from the desires of our ancestral brain-wiring. In this regard, I sit in the techno-utopian camp, albeit with an eye to what could go wrong.

Using resources in space to build human habitats is analogous to dandelions finding a home in the cracks of pavement. The very opposite of paving paradise.

Very well said indeed George. I think there is a fundamental unwillingness to confront greed or a deliberate desire to deny man’s worst instincts fueled by short term greed. The whole consumer society where everyone is urged to “need” every new consumer item, is fundamentally dangerous and flawed. Don’t confuse need with want I say. C.S. Lewis spoke about this in his science fiction trilogy. Greed is one of the most dangerous of all human flaws. Some say hubris is even worse and there is plenty of that to go around as well. Possibly civilizational collapse is our only way forward to allow for humans with different attitudes and viewpoints to try again, but sadly they would try in a deeply damaged, degraded world. I would think science fiction will venture into this as time goes on and things continue to get worse.

It would be interesting to see how much the moon can play into our expansion. There is an enoumous amount of material available of all of the elements we need. There is certainly area for huge amounts of electrical power to be generated and maybe even transmitted back to earth or near earth for consumption via phased arrays. Lasers on the moon would also allow us to land craft on the moon and accelerate them off without huge infrastructures other than solar power panels.

If we did use a laser to slow down a space craft we could actually reuse its in coming energy into a moon electrical grid. A spacecraft weighting many tons and having a few km/s energy has a lot of energy to give back.

Even with 100% energy conversion of teh energy to the laser light and the capturing of the decelerating ship’s energy, wouldn’t that mean that the energy needed to power the laser be balanced? If the efficiencies are low, then would this make much sense?

Well if you are going to land on the moon with a rocket you will need to bring your fuel from earth which cost 50 to 100 times the weight in fuel to get it there. On the moon you have plenty of solar power and a large area to set up your laser system and you don’t have a huge spray of rocket exhaust hitting the surface which could damage equipment. It could also relay power back to earth and the local neighbourhood.

I am not clear what propulsion you intend to use to land and take off from the Moon. 1/6 g requires a lot of thrust and therefore expulsion of propellant. What propellant are you considering that would not disturb the regolith?

The only purely electrical methods to land are tether systems (skyhooks, space elevators) and electromagnetic (maglev). The latter system was depicted in KSR’s “Red Moon” at the Chinese city on the Moon, Ian McDonald’s Luna novels, and of course, Clarke’s short story, “Maelstrom II”. The space elevator is doable with existing plastics like Kevlar, although the length is extremely long.

How you would use lasers other than to launch small solar sails, I am unclear. Lasers for propulsion in a gravity well usually require expelling mass, which has to come from somewhere, and has to go somewhere, typically down to the lunar surface when it will “kick up some dust”.

Both the elevator and the maglev could offer partial energy recovery.

The laser system would recycle the laser light between the spacecraft and ground reflectors. The recycling of laser light allows more momentum to be transferred between the craft and ground. It would also allow it to be used on the ground without the need for a huge electromagnetic setup but rather with just a simple maglev system. As the moon is developed more and more dust will get kicked up which will cause contamination issues and potential damage to surface equipment.

We have discussed this before. It is one thing to demonstrate this in the lab with the moving object mounted on tracks, but very different with a real spacecraft trying to land or take off. Just look at the difficulties of maintaining a sail that can ride a beam. You want a spacecraft that is on approach, from orbit, to maintain a perfect orientation to a beam that must bounce a large number of times between the ground and the vehicle to maintain a thrust to decelerate and land the craft. Maybe it is possible, but my imagination fails me. I would like to see a demonstration in space, perhaps from outside the ISS, that could accelerate an object at fractional g with a modestly powered laser using this approach.

Given that the main beam must bounce back and forth between 2 perfectly aligned mirrors, I am guessing that some means would be needed to maintain stability and orientation – perhaps auxiliary lasers bouncing off control mirrors to maintain orientation? All this control has to be very fast to ensure the main beam continues to bounce correctly to provide the needed thrust.

Have you looked at the energy that is reflected from the mirrors to maintain the needed thrust assuming an areal density for some mirror surface area and the vehicle mass? Are the energies feasible without vaporizing the mirror (and the vehicle)?

I can see lasers as a beamed power source to heat a propellant for rocket propulsion as a more viable approach.

It would be a shame if we had a space elevator with mobile ground unit to move around and the cable got snapped by a rock flying from the surface at escape velocity which is possible.

The laser produces around 6.6 N per gigawatt reflected and if we can expect a 1000 bounces, proven in a lab, it would be around 6600 N of force to slow the craft down. Now we only need to slow it down over a short distance provided the g forces are within limits so aiming is less of an issue. The laser light can then be bleed off too power other equipment or stored.

Let’s assume the simplest task. Launch vertically with no lateral velocity to make orbit. Assuming your 1 GW laser, with 1000 bounces (no reflection loss or leakage, and a net 6600 N force. That would support around 660 kg of mass hovering in a 1g gravity well.

Let’s use the Apollo LM ascent stage as a referent. It had a gross weight of 4700kg, and a trust:(lunar)weight ratio of about 2, ie (4700/6)2 = ~=1500 kg force.

Your 6600N laser would generate about 660kg-force. So in the lunar gravity, supporting a 2:1 thrust: weight ratio, the ascent craft could mass around 2000kg on Earth or about 45% of the LM gross weight.

If the craft had propellant, after the lasers were turned off, perhaps after a more modest velocity and height, the conventional rocket engines could be fired to create the needed horizontal velocity for orbit and well away from kicking up dust on the surface. The laser would act more like a JATO unit or ramp launch saving propellant and keeping the lunar surface undisturbed. If teh reverse maneuver was used for landing, so that the rockets would place the craft some kilometers above the surface with zero horizontal velocity, the laser could decelerate the craft with a vertical landing.

Breakthrough Starshot envisages a 1-10GW/m^2 laser energy hitting the sails. For teh proposed 1 GW laser with 1000 bounces, both the craft and ground mirrors will need to reflect 1 TW of energy. That suggests a circular mirror of radius 5.6-17m to withstand the Starshot energies on the mirror. A major issue will be keeping the mirror on the craft low mass yet stiff enough to prevent warping under acceleration, perhaps by a trussed design with added rotation.

Perhaps doable if my calculations are correct.

In practice, if the laser is just to be used as a launch assist, then the mirror could detach and return to the ground rather than remain an integral part of the craft, although that would require some means to pick up mirrors in orbit prior to descent.

Perhaps a laser slow down initially to almost the surface and energy storage and then a final burn into an exhaust catcher. If we glassify the ground for a suitable distance around the landing site and then provide a chamber connected to a underground lava tube we could cool the exhaust gases for reuse. Lava tubes go for great distances and are very cold so ices should form from the exhaust materials. Dust we all can see is going to be a problem on the moon and will cause issues. Lasers on the moon will save a lot of infrastructure issues and will more than likely power a space elevator design as well.

Forgot the link

https://www.theverge.com/2019/7/17/18663203/apollo-11-anniversary-moon-dust-landing-high-speed

I have one more question concerning infrastructure and interstellar probes. If a probe is accompanied by an AI do we have to ask the AI whether it wants to go if it is sentient? This is the question of volition. I would say we will absolutely have to deal with volition and AI’s in the future. These are SF questions today but for how much longer? Mistreatment of AI by humans must be considered criminal at some point surely? Sending a single AI on an interstellar voyage with no chance of return must be considered unethical surely as such an intellect would probably be destroyed by loneliness and isolation even with occasional contact with Earth.

I think it is more complicated than this. A human-level AGI should be treated as if it is a human – up to a point.

Humans are not always given a choice, e.g. in war, so perhaps an AI might be similarly coerced. AIs might well be indoctrinated to want to journey to the stars as an almost religious mission. The question of choice becomes irrelevant.

We cannot assume that an AI would experience an interstellar voyage as would a human. Whilst our minds are locked into real-time (whether relativistically time-dilated or not, an AI might well be able to adjust its “clock speed” and turn itself off and on, changing the perception of time. A million-year journey at STL speeds might pass very quickly to such an AI.

Unlike a human, an AI could be exactly duplicated, so that only its identical twin might go on the journey, while the other continues locally. That offer may be enticing if there is a reward for doing that.

We shouldn’t assume an AI must be sentient/conscious. It could be a very powerful, but non-sentient mind. If it cannot experience the qualia implied, “loneliness”, etc, then like any machine we should not have any moral qualms about sending it on such a journey. Personally, I would be more concerned about sending a mammal or bird on a risky or deadly journey, than such a machine mind, as the animal would have more sentience than the AI.