John Barrow has been on my mind these past few days, for reasons that will become apparent in a moment. In my eulogy for Barrow (1952-2020), I quoted from his book The Left Hand of Creation (Oxford, 1983). I want to revisit that passage for its clarity, something that always inspired me about this brilliant physicist. For it seemed he could render the complex not only accessible but encouragingly pliable, as if scientific exploration always unlocked doors of possibility we could use to our advantage. His was a bright vision. The notion that animated him was that there was something in the sheer process of research that held its own value. Thus:

Could there be any shortcuts to the answers to the cosmological questions? There are some who foolishly desire contact with advanced extraterrestrials in order that we might painlessly discover the secrets of the universe secondhand and prematurely extend our understanding. Such a civilization would surely resemble a child who receives as a gift a collection of completed crossword puzzles. The human search for the structure of the universe is more important than finding it because it motivates the creative power of the human imagination.

You can see that for Barrow, the question of values was not separated from scientific results, and in a sense transcended the data we actually gathered. He goes on:

About 50 years ago a group of eminent cosmologists were asked what single question they would ask of an infallible oracle who could answer them with only yes or no. When his opportunity came, Georges Lemaître made the wisest choice. He said, “I would ask the Oracle not to answer in order that a subsequent generation would not be deprived of the pleasure of searching for and finding the solution.”

Image: Cosmologist, mathematician and physicist John D. Barrow, whose books have been a personal inspiration for many years. Credit: Tom Powell.

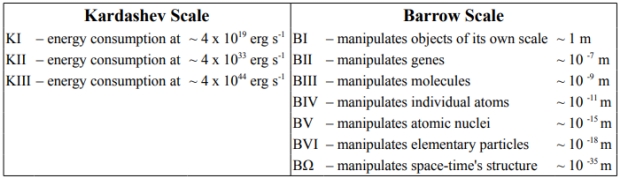

Leave it to Lemaître (and Barrow to quote him) as we reach beyond the immediately practical to unlock what it is about human experience that compels us to push into new terrain, whether it be physical exploration or flights of the imagination as we pursue a new hypothesis about nature. Barrow comes to mind because we’ve just been talking about the scales by which a civilization can be measured. Some of these are well established, as for example the Kardashev scale, with its familiar Types I, II and III keyed to the scale of a civilization’s energy use. In Clarke’s The Fountains of Paradise we find an alien scale based on the use of tools. It’s possible to imagine other scales, and Barrow’s own contribution takes us into the nano-realm.

As best I can determine, Barrow first floated the scale in his 1998 book Impossibility: The limits of science and the science of limits (Oxford University Press). Inverting Kardashev, Barrow was interested in a civilization’s ability to control smaller and smaller things, relying on the observed fact that as we have explored such micro-realms, our technologies have proliferated. Nanotechnology and biotechnology are drawn out of our ability to manipulate matter at small scales, and in fact the development of nanotech is one marker for a Barrow scale IV culture.

Barrow I: The ability to manipulate objects at the same scale as the person or being involved. In other words, simple activities involving basic tools.

Barrow II: The control of genetic information.

Barrow III: The ability to control molecules.

Barrow IV: The ability to control individual atoms.

Barrow V: The manipulation of atomic nuclei..

Barrow VI: Control of elementary particles.

Barrow Omega (Ω): The ability to control fundamental elements of spacetime.

Table: Energetic and inward civilization development. Kardashev’s (1964) types refer to energy consumption; Barrow’s (1998, 133) types refer to a civilization’s ability to manipulate smaller and smaller entities. Credit: Clément Vidal.

I’ve drawn the above table from a paper by French philosopher and SETI scientist Clément Vidal, who is one of the few who have explored this realm (citation below). Here we get both Kardashev and Barrow at once, a convenience, and central to Vidal’s argument that black holes are going to draw advanced civilizations to extract their energies and explore what he calls “the computational density of matter.” On this score, it’s interesting to note that Freeman Dyson proposed in 1979 that a civilization exploiting time dilation effects near black holes could survive effectively forever (a later revision had to take into account the accelerating expansion of the universe).

What all this means for SETI is intriguing – almost punchy – and I’ll send you to Vidal’s superb The Beginning and the End: The Meaning of Life in a Cosmological Perspective (Springer, 2014) for a deep dive into the concepts involved. But consider this for a starter: Dysonian SETI assumes civilizations far more advanced than our own, the reasoning being that their works should be apparent even at astronomical scales. Thus searching our astronomical data as far back as we can could conceivably flag an anomaly that merits investigation as a possible civilizational marker.

What Clément Vidal has been investigating is where such markers would turn up, and for this he deploys the scales of both Kardashev and Barrow. I think the easiest assumption is that we would find an alien civilization at its home world, but of course this needn’t be the case. Vidal speaks of ‘attractors’ as those sources of energy that an advanced civilization would increasingly exploit. Take a culture a billion years older than our own and ponder energy needs that might require it to exploit things like the energies of close binary neutron stars or black holes themselves. Such a civilization would be far flung, with operations well beyond its local group of stars.

Now ponder Barrow Type Ω. This ‘omega’ culture is free of the constraints of spacetime, having achieved the ability to manipulate both. It’s anyone’s guess whether such a civilization would be noted by achievements on a truly celestial scale, or whether its works would actually be embedded in the nature of space and time themselves, so that to us they appear the simple functioning of nature. In this mode of thinking, the more advanced a civilization becomes as it moves up the Barrow scale, the more it begins to effectively disappear. Barrow thus channels Richard Feynman and anticipates Lee Smolin’s notions about cosmological evolution, a kind of self-selection for universes.

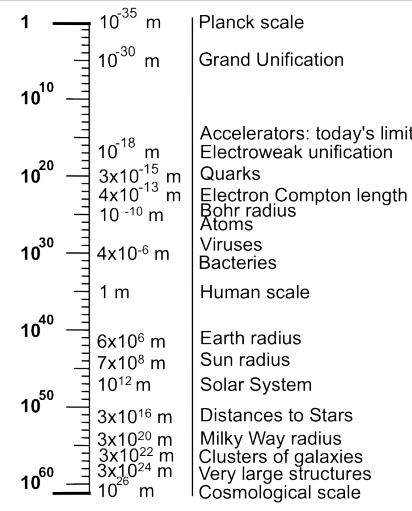

I’m going to swipe the chart below from Vidal’s 2010 paper on black hole attractors, showing the entertaining fact that as he puts it, “from the relative human point of view, there is more to explore in small scales than in large scales.”

Table: That humans are not in the center of the universe is also true in terms of scales. This implies that there is more to explore in small scales than in large scales. Richard Feynman (1960) popularized this insight when he said “there is plenty of room at the bottom”. Figure adapted from (Auffray and Nottale 2008, 86). Credit: Clément Vidal.

Futurist John Smart has dug into what he calls STEM Compression, with STEM in this case meaning Space/Time/Energy/Matter, and the compression being the idea that in terms of density and efficiency, we can as Vidal puts it “do more with less.” For going deeper into the Barrow scale, we see that as things get smaller, we are not hampered by the speed of light problem. In fact, our endgame barrier is at the Planck scale. A Kardashev II civilization extracting energy from a rotating black hole using technologies far up the Barrow scale may well be indistinguishable from an X-ray binary of the sort that has been cataloged in the astronomical literature.

Such speculations are on the far edge of SETI (and again, I refer you to Vidal’s book), but it’s also true that whether or not extraterrestrial civilizations exist, our own ability to chart futures for an expanding civilization may well come in handy if we can somehow punch through whatever ‘great filter’ may be out there and become a species that survives on the scale of deep time. There is no knowing whether this is even possible, and it may be that the galaxy is filled with the ruins of those who have gone before us.

It is also true, of course, that no one may have gone before us. Maybe N really does equal 1. But I return to Barrow: “The human search for the structure of the universe is more important than finding it because it motivates the creative power of the human imagination.” And the human imagination is currency of the realm in matters like these.

The Vidal paper is “Black Holes: Attractors for Intelligence?” presented at the Kavli Royal Society International Centre, “Towards a scientific and societal agenda on extra-terrestrial life”, 4-5 Oct 2010 (abstract). The Dyson paper is “Time Without End: Physics and Biology in an Open Universe,” Review of Modern Physics 51: 447-460 (abstract). My eulogy for Barrow is On John Barrow. John Smart contributed a fascinating essay on cosmic evolution in these pages in The Goodness of the Universe.

Paul,

This is the perfect response to my “small imagination” comment from your last post. Two things strike me; first it takes a big imagination to contemplate converting an asteroid or moon into a “ship”. Wow! That’s a non-trivial project to be sure. But also, that we don’t know what we don’t know, therefore the pursuit of a project like interstellar travel presents the opportunity to expand the range of human inquiry and/or like Feyerabend, expand the methodologies we bring to bear on interesting questions. If the project is “send something interstellar” then robotics is an interesting topic of inquiry. If the project is “send humans interstellar” then you will need to come up with more than robotics. So, are we allowed to imagine ways to avoid the insoluble problems of interstellar travel for living beings? Or like Rocky, the only way through is to go toe-to-toe and overcome reality?

Sure, we can imagine human interstellar travel and its solutions. Why not? My own belief is that it is going to take technologies we don’t even have on the board yet, if it ever happens. I’m far more sanguine about robotics and AI. At this point all of it is imagination-stretching, but that’s an exercise I always recommend.

We always assume an intelligent civilization will always exploit every new technological development to its ultimate. What if a truly wise species only tries to advance in those areas where the cost/benefit analysis is most favorable?

Perhaps the longest-lived species are those who are essentially conservative. The ones who consider the potential drawbacks of aggressive growth and spend a great deal of effort and study in examining possible problems and consequences of new technology. Perhaps they prize optimum compromise and careful planning more than they do unrestricted and undisciplined growth. This does not necessarily imply a race of Luddites and tree-huggers, just one of careful husbandry and low-impact. They will always have a Plan B.

Even in our predatory and competitive business culture we often give great lip service to the “careful investor”, and “orderly growth”, “disciplined development” and “avoiding destructive competition”—-even if we don’t always practice it. We intellectually understand the value of careful planning even if we are occasionally seduced by the often highly short-term profitable balls-to-the-wall approach.

And most likely, old and successful cultures will have learned this after multiple failures. Explosive growth may provide temporary advantages to isolated communities expanding into unoccupied wilderness, but crowded and highly populated environments may require much in the way of sharing, cooperation, and knowing when enough is enough.

We often speak of the default condition as “if you’re so smart why aren’t you rich?” Perhaps the appropriate one should be “if you’re so rich why aren’t you happy?”

Please forgive me if my comments here often seem to reveal a deep suspicion of the competitive, aggressive, constantly expanding culture determined to fill up every nook and cranny of unoccupied space for all time. Perhaps that is only a characteristic of young species struggling against stiff competition. It is not necessarily the mind-set of old, mature societies that have survived a long process of natural selection. Or then again, perhaps it is only the indicator of individuals who are obsessed with activities like imperial conquest, exploration, growth and other concepts associated with never-ending expansion. This site, and others like it may select for that mentality; for all we know, the universe may tend to prune them out.

@henry. In Kevin Kelly’s book What Technology Wants he includes a chapter on the process of evaluating new technologies by the Amish. In 1975 we restricted gene manipulation by the agreement at the Asilomar Conference on Recombinant DNA, a technology now gaining rapid expansion, especially with the use of CRISPR technology.

The problem I see with restrictions is that they require increasingly draconian laws and even surveillance to keep them restricted. The Amish can do that in their small community, but there is at least some release for those who leave. Humanity is currently a single-world species. We see actions to break technology “taboos” and agreements all the time, not because of business, but for other reasons, including “because we can”. Some of those restrictions seem over cautious like dumbing down toy chemistry sets. We also see overreactions by law enforcement, like the concern that a long-distance run marker might be anthrax.

While it might be possible for a “mature” civilization to restrict certain technologies, unless there is universal acceptance by the population, it will require very restrictive laws and their enforcement. This seems like a dystopia to me, and we seem to be reaching for it even as some agencies seem to be pushing other technologies with potentially harmful possibilities.

My view is that we might be better off finding ways to safely do the experiments off-world, whether by colonizing other planets or restricting some experiments to off-world sites. A delightful example of this in fiction is the manga by Hoshino, but written by James Hogan, The Two Faces of Tomorrow. The premise is that an advanced AI starts evading human control. In order to determine if new software can prevent it, they do the experiment in a space habitat (a Stanford Torus) to contain any serious problems. It is an idea that has been explored elsewhere, like doing genetic manipulation experiments in a space station module. Obviously, as technology becomes more potent and can be used by individuals, there is always the issue of those who will do prohibited things. [Take the 3D printing of plastic guns, which at one time it was suggested the printers be made to not print such objects.] It is a conundrum, but without universal individual acceptance of democratically agreed upon technology bans, I fear that a highly regulated civilization will result – not one I would care to be part of.

Alex, I’m not coming out in favor of US managing and restricting technologies (although we sometimes do just that and piously pretend we don’t). I just think other cultures may do that, and perhaps for very different reasons than we might. Who knows what their social and cultural systems are, or how they are politically organized, or if those terms are even meaningful in their situation. What we may see as freedom and innovation they may see as undisciplined lack of restraint, even carelessness. Even in the modern classroom, what one teacher sees as chaos and disruption, another may characterize as structure and order, yet a third may see freedom and innovation.

I was brought up bi-culturally and I may be overly sensitive to these contrasts. But even as a child, I quickly learned the superstitions of my tribe were not necessarily the laws of physics. And I very quickly learned that our views of the uncivilized and barbaric customs of the mainstream culture were not that different from the ways they in turn viewed us. In fact, this is what first drew me to science fiction, and then science. Alien societies, or those set in distant times, were often riddled with inconsistencies (when viewed by the baffled visitor or explorer}. I was exposed from early on to an alien culture, one that viewed mine as alien. Armed with this insight, I had access to tools neither my family at home, or the kids I ran around with at school had. And most important, I learned that sometimes subjectivity itself can be harnessed and exploited.

I recall reading one science fiction story where the aliens (they were actually human colonizers on another planet) had a society that practiced ritual murder, vendetta and dueling, yet they felt that organized warfare between communities was barbaric and disgusting. The Terran explorers who were visiting them felt just the opposite! And these were both human societies. Truly alien cultures may be a lot stranger than that.

So take the Amish example. They are a homogenous population with total control by their elders, effectively a group dictatorship. Will they outlast the developed world – idk.

Biospheres are full of species that are evolving, sometimes slowly in large populations, sometimes fast in small founder populations. But adaptation and technology do include change. When we used fire to stampede mammoths off cliffs – should our ancestors have considered that they were dooming that source of meat? Indeed, hunting without care will end food animal populations. However, once a species has culture, how do you end “survival of the fittest” that allows for new inventions and techniques?

@Henry. Our hierarchical plains ape societies have tried various means of control. Top-down control by diktat doesn’t necessarily help survival in the face of change, as the Mayans found out with drought. “Freewheeling” laissez-faire doesn’t help either, as we are seeing in real-time with changing our use of fossil fuels. Would it be easier with a global dictator (even a fanciful computer or AI), or even worse?

A hypothetical alien civilization might be long-lasting but stuck in a very primitive state, like the surviving hunter-gatherers on Earth. How long would the many cultures on Earth have survived in their state without the European expansion? The evidence we have suggests all cultures, even static ones, eventually fail.

I find it difficult to envisage how you get to an advanced technological civilization without active invention and experimentation. For example, the pre-European invasion of North America saw the early extinction of the mammoth, but an eventual polity of different tribes living in a Malthusian state with some stable practices to prevent the over-use of resources, such as the bison in the Great Plains. But as we know, those cultures were overwhelmed by the Europeans. South and Central America have a similar history.

Is there any combination of biology and social structure that can control technological development to only move in a non-destructive way? This must exclude wars (which hasten technology development), restrict individual choices, and make consistently good choices that can be maintained globally without making unforeseen errors (we do that all the time as we cannot know the consequences of our technologies). My imagination fails at this point. It seems to me that thinking any such civilization can exist is like believing in an omniscient deity who can see the future consequences of any action in a multiverse and pick the best action. But this is impossible, like playing an infinite board chess game where the rules can change with every move. This metaphor suggests that only a constrained board size with fixed rules is computable where the “end game” is the longest run of moving pieces before oblivion happens – like small tribes of stone-age people that might survive until some external event ends their population, rather than an internal one.

As Douglas Adams joked in THHGTTG, just before the Vogons destroyed Earth, a woman figured out how humans could live in peace without needing their cult savior to be nailed to a cross. The Vogon Constructor fleet was an external event, unforeseeable by Earth people, even if this wonderful way to live in peace had become a successful way of life. Would we have to live in a primitive, pre-technological state like the small population of the Eloi in Well’s “The Time Machine”, perhaps after the traveler has destroyed the Morlocks? Kim Stanley Robinson once stated that “pocket utopias” were never explained how they reached that state, which he tried to remedy in The Gold Coast, the last of his “Pacific Edge” trilogy. Interesting as that utopia was, it seemed horribly static and unsatisfying because any utopia resists change – it has reached the highest peak in the social fitness landscape, with nowhere to go but down. This seems to be the case in Hesse’s “The Glass Bead Game” where nothing much of consequence seems to happen (IIRC).

Let me return to the Amish, or indeed any group or population that prefers to resist change, or even return the culture to an earlier time. Should they eschew all the benefits of our science and technological civilization? Should they deny themselves the use of modern medicine – vaccines, antibiotics, painless surgery? Do they deny themselves COVID-19 vaccines and pay the price, perhaps considering it a natural (or deity-ordained) culling like so many in history?

I am certainly trapped by my species and culture. But as Cabal opines at the end of the movie version of Things to Come, “It is to be the universe or nothing!”. This seems to be the only path forward, making discoveries, trying to curb and control the most dangerous technologies, but moving forward with the risk of oblivion, but with the goal of an endless and unstoppable spread into the universe of our collective history and achievements. We should attempt this assuming that we are free to do so until that is proven false.

The question we might like to know is: “Do technological civilizations like ours survive for a long time, or do they fail?”

In some ways, this is not unlike asking how long we as individuals will live. Barring accidents, we may soon have approximate information in our genomes.

Do we want to know, or not? I’m reminded of Ray Bradbury’s short story: The Toynbee Convector in which our contemporary civilization passes through an environmental disaster by being told that the future is bright. So civilization aims to make that future.

If ETI tells us “yes, ” do we find ways to ensure long survival? If “no”, then what?

Regarding Barrow’s “manipulating space-time structure”. Aren’t we back to Stapleton and Clarke again? Clarke, in particular, describes such intelligence in The City and the Stars, and we do not doubt that Dave Bowman as a “star child” can do so by instantaneously traveling across the stars and then manipulating atoms to detonate orbiting nuclear weapons. In both cases, the civilizations are very old – whether terrestrial in TCATS, and alien in 2001:ASO. Sagan’s Contact suggests that ETI has created our universe and left clues in some irrational number sequences. And yet we are at Barrow’s BIV, maybe BV, and possibly starting BVI (at least photons) level. Can we expect to be B_omega in a century, perhaps with AI help?

Very interesting. I am puzzled by the BII level. What did Barrow mean by manipulating genes before manipulating molecules? Humans knew about molecules long before they discovered genes. Or did he mean manipulating bacteria, like brewing beer or fermentation? I am curious about his reasoning here.

I suppose he meant by manipulating genes you are manipulating large congregations of molecules say via protein synthesis.

It takes no hi-tech to do genetic manipulation. Farmers and stockmen have been doing it for thousands of years, sometimes without even realizing it.

possibly?

manipulating genes = directed breeding, selective seed planting, etc. (<10,000s ya)

manipulating molecules = chemistry with known pathways to create compounds (since c. industrial revolution?)

Humans already operate between Barrow VI and Omega. This is the work being done in Quantum Biology. Practical experiments are being conceived and carried out, perhaps only to detect quantum effects at this point, but can it be long before such biological mechanisms might be manipulated?

“A robin: inside her small dark eye, a quantum entanglement.” Helen Sullivan, The Guardian.

Link to Jim Al-Kalili – A BBC4 Video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bKa3ZNgBxVs

From this body of work (only showcased an old video here) it appears that matter itself undergoes evolution, i.e. the universe itself is alive in some sense. Is evolution itself a physical law? If so it would seem that “life” of necessity appears everywhere. Accepting this as an assumption informs SETI; we need to figure out what kind of events are involved in transitions to more complex forms and how to detect those transitions. If life in this sense arises everywhere, in the first instants of the universe, it apparently requires about 13 billion years of this process to produce life forms that do more than respond to their environments. Maybe we don’t see other intelligent life forms impinging on us because the universe has just recently produced the complexity that can begin to undertake “behavior”, exhibit a will, manipulate its environment. “N” may equal 1, but perhaps only for a while longer?

It is to be recognized that all individual human awareness starts with the modulation by matter of forms of energy further modulated by the 5+ senses into transmembrane voltages and currents conveyed to the brain, and thence through little understood processes manifest in the mind and its awareness.

In ancient traditions that place primacy in awareness the triad of experiencer, expriencing and experience is incomplete without all three: every experience must be considered with the other two for its validation. It is asserted that Reality is not within time and space; rather time & space are in reality: And Reality is bigger than the biggest and smaller than the smallest.

“ Take a culture a billion years older than our own and ponder energy needs that might require it to exploit things like the energies of close binary neutron stars or black holes themselves.” Wouldn’t it be interesting if the civilisations that last a billion years use less energy than ones that last a few thousand years.

Effeciency places a premium on smaller, lighter items with less power consumption, as in the aerospace industry.

Technologically advanced civilizations might minimize power consumption, and even the use of matter to such a degree that the associated disruptions of matter and energy may be mistaken by external observers to be natural rather than artifactual.

Paul wrote :

” the more advanced a civilization becomes as it moves up the Barrow scale, the more it begins to effectively disappear.”

…contact with this infinitely superior civilization would be impossible until we had the means to detect it or become aware of it. We can then imagine that our technical progress would be made by seeking out and then meeting other civilizations in the infinitely great, each of which would bring us knowledge step by step, until we reach the level of Ω civilization. Our ignorance and our quest would then be an advantage, since it would enable us to enrich ourselves. So it’s not so much the goal that’s important here, but rather the path we take.

We can also imagine that civilization Ω discreetly gives us clues to lead us to it, if we consider that we are part of the whole that it manipulates. In that case, it would have already discovered us; probably observed and perhaps even created us? If tomorrow we were certain that our species had been created by another, it would profoundly challenge our civilization and our age-old beliefs, since it would erase the idea of any materially inaccessible divinity. Socially speaking, this kind of contact could create chaos on Earth, and even lead to our own self-destruction. A subject already covered. In other words, we need to strike a balance between a gradual influx of knowledge that maintains the equilibrium of our societies on earth, and a lack of knowledge that inevitably leads to the collapse of civilizations.

I’ll close this parenthesis and return to our civilization Ω: if it has arrived at this ultimate stage that allows it to “disappear”, we can assume that it has not progressed randomly and is therefore evolving. If so, why would it bring us to it? What could such a “super-civilization” possibly gain? At best, we’d be nothing more than an “adjustment variable” that it could observe interacting in the space and time it manipulates… I don’t see what we could teach it in this asymmetrical context.

Now let’s imagine a symmetrical context. If we exclude the notions of conquest and domination [specific to our species & Hollywood ;) ?] what could we share with Ω civilizations since we’d be two all-powerful civilizations over matter and time?

In a way, the need for civilizational contact wouldn’t arise, since to establish a contact is to establish a link that will enable a transfer of information between two or more entities, INEQUAL in terms of knowledge, thus enabling an evolution and/or orientation of one or both parties. If there is a balance in terms of omniscience between the two civilizations, then we find ourselves in a stable, neutral and “unproductive” state …. reminds us of thermodynamics, doesn’t it?

Okay, my reasoning is a bit sad, so let’s give it a way out: we’ve thought all this out in ONE universe, comprising our two civilizations, ours and the Omega civilization. That could be a dead end. But since we’re talking about scale, the situation could change completely if we assume a “multiver”: the two super-civilizations with the same degree of space-time knowledge could then exchange to explore these “multivers”… where the space-time-matter frames would surely be different…

Then, the question becomes: what is Knowledge for?

Fred

I think one could argue that an invisible deity in the sky meets the criteria for an advanced [member of a] civilization. Even the many polytheistic religious gods meet most of the criteria – just read any works or watch tv or movie media to see that.

But regarding the idea that knowledge of our origins would cause social chaos? I don’t know about that. Religions have been doing that forever, yet no major chaos has happened. Darwin and Russell showed that a naturalistic origin occurred, yet the Western World didn’t fall apart. If it could be shown that we are either the result of panspermia, natural or directed, or direct genomic tampering, I don’t see why society could self-destruct.

If a deity manifested itself and stated that it had created humans and that a;; the world’s religions and materialistic theories of human creation were wrong, just what might happen? Some religions would collapse. Others would carry on as their stories may not account for a creation story. Science would no doubt look to understand how we might have been created as we share so much biology with terrestrial life in an understandable lineage – tinkering with existing genomes.

It just might be a good thing if the large religions were abandoned and a singular new one was created giving humanity a single coherent story of our creation.