Studying the rich history of interstellar concepts, I realized that I knew almost nothing about a figure who is always cited in the early days of beamed sail papers. Whereas Robert Forward is considered the source of so many sail concepts, the earliest follow-up to his 1962 paper on beamed sails for interstellar purposes is by one G. Marx. The paper is “Interstellar Vehicle Propelled by Terrestrial Laser Beam,” which ran in Nature on July 2, 1966. Who is this G. Marx?

My ever reliable sources quickly came through when I asked if any of them had known the man. None had, though all were familiar with the paper, but Al Jackson sent me a copy of it along with another by J. L. Redding (Bishop’s University, Canada), who published a correction to the Nature paper on February 11, 1967. It didn’t reduce my confusion that Redding’s short contribution bears the exact same title as Marx’s. My other contacts on Marx had no personal experience with him either but were curious to learn more.

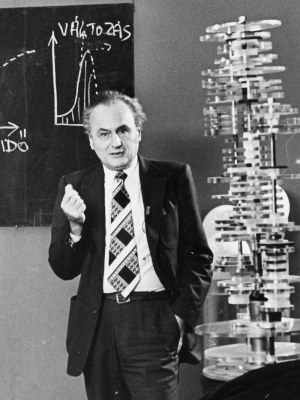

Image: Astrophysicist and science historian György Marx. Credit: FOTO:Fortepan — ID 56238:Adományozó/Donor: Rádió és Televízió Újság. – This file has been extracted from another file, CC BY-SA 3.0.

This is worth digging into because it illustrates some useful facts about beamed propulsion. But first: György Marx (1927-2002) was Hungarian, an astrophysicist and historian of science who is evidently best known for his work on leptons, that class of subatomic particles that are not affected by the strong force and can carry electrical charge or be neutral (the charged leptons are the electrons, muons, and taus). As a science historian, Marx was clearly possessed of a sense of humor, authoring a study of Hungarian scientists in 2000 called The Voice of the Martians.

That title is itself worth unpacking. The reference is to that great influx of supremely gifted scientists and thinkers – among them Peter K. Goldmark, Nicholas Kaldor, Arthur Koestler, Nicholas Kurti, John von Neumann, Egon Orowan, Michael Polanyi, Leo Szilárd, Edward Teller, and Eugene P. Wigner – who were born between 1890 and 1910 and greatly influenced the growth of technology through their work in the U.S. Their gifts struck some as all but other-worldly. The Voice of the Martians has just been re-published in a new edition by Pallas Athéné Books. There’s a helpful review in The Budapest Times, available on Mary Murphy’s fine Unpacking My Bottom Drawer blog.

My friend Tibor Pacher and I joked about the extraterrestrial origin of Hungarians when we met up at a conference in Italy. Tibor is himself Hungarian, and he pointed to the old joke about the influx of Hungarian scientists being of off-planet origin. A Princeton professor upon learning that John Kemeny was Hungarian is said to have exclaimed about the mathematical prodigy “Not another one!” Leo Szilárd, asked about aliens, once quipped “They walk among us, but we call them Hungarians.” The fact that the Hungarian language is non-Indo European makes the joke even better.

Teller, by the way, when told of Szilárd’s statement, took on a worried mien and said, “Von Kármán must have been talking.” And Marx would push the notion even further, noting that Hungarians must have an extraterrestrial origin because the names of so many of them, like Szilárd, von Neumann, and Theodore von Kármán, show up on no maps of Budapest, but there is a Von Kármán crater on Mars, and another on the Moon, along with craters named for von Neumann and Szilárd. Case closed.

And then there is nuclear physicist Friedrich “Fritz” Houtermans, himself born near Danzig but knowledgeable about the Hungarian element, who opined:

“The galaxy of scientific minds, that worked on the liberation of nuclear power, were really visitors from Mars. They found it difficult to speak English without an alien accent, which would give them away, and therefore they chose to pretend to be Hungarian, whose inability to speak any language but Hungarian without a foreign accent is well known. It would be hard to check the above statement, because Hungary is so far away.”

What a fascinating bunch. Marx saw this bulge in the demographic of prodigies and scientific wizards known in Hungarian as a marslakók, the term for ‘Martians,’ as a cultural phenomenon. He interviews and writes about them with insight and affection. Here he is in The Voice of the Martians in conversation with Teller as the latter reminisces about Leo Szilárd. Marx as historian was clearly able to extract great anecdotes from very deep thinkers:

“[…] fortunately, there was a Hungarian in America, Leo Szilárd, who was a versatile person. He was even capable of explaining the concept of a nuclear chain reaction to the Americans! Yet there was one thing that even Szilárd could not do: drive a car. In the summer of 1939, I was working at Columbia University in New York, just like Szilárd. One day, he came up to me and said, ‘Mr. Teller, I am asking you to drive out with me to Einstein.’ […] So, out we drove on August 2. The only problem remaining was that Szilárd again did not know where Einstein was staying for the holidays. We started asking around but nobody knew. We asked an eight year–old girl—she had a nice ponytail—where Einstein was living. She did not know either. Finally, Szilárd said, ‘You know he is that old man with long, flowing white hair.’ Then the girl gave us the direction, ‘He’s staying in the second house!’ We entered; Einstein was cordial, offered tea to Szilárd, and—being democratic—he invited in the chauffeur as well. Szilárd pulled a letter from his pocket addressed to President Roosevelt […]”

Leo Szilárd’s own sense of humor was a kind of magic dust that affected other scientists working on nuclear topics. He once announced his intention to write down everything he remembered about working on nuclear fission, “not for anyone to read, just for God.” To which Hans Bethe replied, “Don’t you think God knows the facts?” And Szilárd replied, “Maybe he does, but he does not know my version of the facts.”

All this is fine stuff, and one reason why I wander off down sideroads when I start asking questions about scientists. But it’s time to get back to interstellar concepts, because György Marx had ideas about reaching other stars that helped to focus the attention of other scientists on what Forward had been saying for some time, that interstellar flight was possible at the extreme end of engineering, and that it behooved scientists to be studying the best ways to accomplish it. But Marx’s specific choices for beamed propulsion would turn out to be ill-advised, as we’ll see next time.

As a European, I have always been surprised by the brilliant minds that exist in Central Europe, even today ; many have an amazing ease of learning. (I have a Ukrainian friend who speaks four languages perfectly including French better than me yet she had never left Ukraine before war !)

I also remember a Hungarian work colleague who was cleaning up a school…yet when I was chatting with her, she was able to calculate the height of the stairs in architecture or just having fun juggling the ASCII codes of computer keyboards :)

I think we don’t know all these great scientists as Marx because somehow the communist regime “invisibilized” them (Remember that S. Korolev could have been unknown because he was bound to secrecy under Stalin in the 50s and many people do not know K. Tsiolkovsky).

On the other hand, I recognize well this quirky humor – like the andecdote of the ants in the blog – it is not insignificant: it comes from the harshness of life in the communist world; Turning things into derision was a way to escape by thinking and thus survive (read the communist jokes, some are very funny :)

Finally the article also reminds me of Karel Capek who “invented” the word “robot” from Slavic languages. is it not this object that we send into space? ;)

Thanks Paul for this discovery; there are some other photos of Marx here:

https://real-i.mtak.hu/1263/

Fred

Thanks, Fred. Those photos will come in handy as I put together the next piece.

still some information about Marx here (we see very well his bionic eye and the bald forehead typical of Martians despite his humanoid disguise that does not fool anyone …and if he doesn’t know how to play chess, then it’s on, is one….they already did the trick… ah ah :D

https://pubs.aip.org/physicstoday/article/56/10/81/1040516/George-Marx

Thank you really much for this article! It is a pleasant surprise as a Hungarian. We had several great 20th century scientists, however sadly most of them had to leave the country because of politics.

The one I can think of present day is Katalin Karikó, for mRNA research. Any honorable contemporary mentions, anyone?

@Adam

Your testimony is therefore valuable and it would be nice if you told us about your country or translated the docs on G. Marx. :)

Paradoxically the severity of the communist regime has pushed people to work hard even with their brains and the quality of education seems to be superior to the musty to the western europe. Sometimes the communist Party, gave them big material means for research, (space conquest) alas at the expense of the people who wandered all day in the queues in front of the stores to find a piece of meat (Adam knows what I’m talking about – my grandmother was Polish ;) So the whole created a context of scientific research, once again invisibilized to the west by the Berlin Wall. Note that this is still more or less the case at present or, for example, in France, the current research of Central European countries is not well known.

The “brain drain” was often due to material living conditions in these countries but also to the fact that freedom of expression was very limited, which is incompatible with scientific research since it is above all an exchange of ideas, If today it is possible with the Internet, it was not the case at the time: it was necessary to be “in” – and follow the research guidelines of the Party – or “outside” and become a traitor: not funny. Beyond the persecutions, it is understandable that many scientists from Central Europe have exiled themselves. Normally, Research has no boundaries since it is a common good to humanity, but it is still where there is the wallet;)

For information, France has had brilliant brains; currently, there are still some but many are in the Anglo-Saxon countries or in Asia because the credits for research are zero and the school system is in ruins. (it was excellent in the 70s because De Gaulle WANTED researchers, engineers of skilled workers => Concorde; Citroen; Nuclear; Minitel etc The anecdote is little known, but France also grabbed German scientists after 1945, which allowed him to develop his first rocket called “Veronique” and access to atomic weapons. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/V%C3%A9ronique_(rocket)

This is a little off topic, but it is worth remembering that research is closely linked to political powers. Bill Gates the “little genius” who tinkered his computers in dad’s garage is a myth, he would never have been able to sell Windows if the US Treasury had not opened the markets to him…

Am I not a little right ? :)

Fred

Sure I can help with some translations, but I’m not a professional in that area. Which ones in particular?

Communist regime was just one of the problems in the 20th century. World wars, nazis, too. Many of the scientists mentioned in the article were Jewish-Hungarians, and therefore they had to flee. Many didn’t make it.

If there is something we can learn about this, I think it is that science only flourishes in freedom. Something we should remember for future colonies in the Solar System or beyond.

What made me smile was the joke about us who speak Finno-ugric languages to be immigrant aliens. A joke I made myself, though in a way people knew I was just being silly. I am a bit more serious with my hypothesis that various Finno-ugric languages used to be spoken all over Europa before the Caucasians arrived and brought the Indo-European language that is the national languages in most countries today.

That’s an interesting hypothesis, Andrei, and I suspect it’s true or close to it. But where would, say, Basque fit into it?

Thank you for your nice reply Paul.

While my hypothesis sound plausible for a handful of reasons, it’s unprovable as we do not have any written records.

And while a friend of mine expressed the idea just some weeks ago that Basque in some way would be distantly related while modified with contact with the Moor etc. I could not agree, and admit that Basque is a bit of a mystery.

I rather tend to think it might be a remnant of a different ancient language that never spread over any larger region and only was used in the most southwestern corner of Europe.

This while Finno-Ugric languages not only is the national language in several countries, but also the language for minority groups in several others.

I am not Hungarian. I am not a scientist either but only a hobbyist in this area. However, my other hobby is listening to progressive rock music and I am now in goosebumps, since an album I love and admire makes more sense after this article. The album is Marsbéli Krónikák (the Martian Chronicles, 1984) by the Hungarian group Solaris. The intro has very adorable Martian baby noises. The connection is now clear. It seems I have been listening to the voice of the martians for years!

Here is the full album of The Martian Chronicles for those who are interested:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QJTOpVgvwWM&t=13s

I was not aware there was a band named Solaris, but I like it.

Yet more evidence that music can bridge the gaps between the Two Cultures of C. P. Snow…

https://www.rbkc.gov.uk/pdf/Rede-lecture-2-cultures.pdf

@ilkay

Progressive music is a bit like music that allows you to travel through the universe, looking at the stars with a good headset (and get kicked out of math class the next day:) I liked this very futuristic cover of K Schulze.

https://www.amazon.es/Audentity-Klaus-Schulze-2015-08-03/dp/B01KAPQPEO

As for Tangerine Dream, “Rubycon” even served as a credits for a French TV show on space in the 80s whose title was great: “the future of the future”:)

Welcome to the club!

Hi Paul

A very interesting read as always. I find out something new with each of your postings and also from the comments too.

Thanks Edwin

@Fred,

The Russian emigrés that we got in Silicon Valley after the fall of the Berlin wall and the option to leave Russia were clearly very superior in some technical and mathematical regard. This may have been a selective issue, but clearly they were generally very highly educated and capable.

Hungary is no longer a communist state, but now a member of the EU but with an authoritarian government (“illiberal democracy”). If Hungarians are still producing highly skilled scientists and technologists, I am not aware of it. (Maybe they no longer want to emigrate to the USA?)

I have the Hungarian tv series “Pirx kalandjai” (Pirx the Pilot?) that is based on the Stanilaw Lem book of “Tales of Pirx the Pilot”. For a short period, I was able to get audio to text from each episode and then get it crudely translated. I then edited the subtitles myself to correct obvious errors. Sadly this service is no longer available. As language translation improves and I hope to have another shot at getting better audio to text and text translation of Hungarian to English. If there is a version of the series (5 episodes?) that has good English subtitles I would love to get it. The special effects are extremely crude, but AFAICS the humor of the stories does get through.

Democratically elected government I may add, they have not gone after political opponents yet..but then all they have to do is copy another so called ‘Democracy’.

Looking like a great filter event is coming, I hope not but I would not be surprised.

@Michael

Hungary’s democracy is more like Putin’s Russia. Orban’s Fidesz party has so changed the constitution and controlled the media that it has been impossible to unseat him and his Fidesz party.

How Viktor Orbán Wins.

Lol, changed the constitution and media control…mmmm….. was that not a gripe in the good old US of A from the other ‘political party’….. well at least locally. Never mind back to science.

I found this interview with G Marx where the scientist talks about the 21st and a little bit about SETI. What is interesting is that they did not separate themselves from the philosophical and religious side in their research and it is even visibly what made them advance. (I made a machine translation of the text in English – good reading)

Source : https://www.termvil.hu/archiv/tv2002/tv0205/marx.html

—————————————————————————————————————-

Travel in the XX. century to the XXI. century

Conversation with academician György Marx

„ No: there can be no question of any oeuvre – conversation ” – is categorically answered by György Marx when the reporter asks him to talk about his career and his life on the occasion of his 75th birthday. „ I don’t care about the past ” – is rejected by the physicist. „ Okay, then let’s talk about the future ” – answers the reporter. „ Only interested in the future – is reported by György Marx – and has always been so. ” The reporter tried to persuade the scientist physicist to talk about what had happened, what had come true and why everything that György Marx envisioned in his youth, and what could be realized in the 21st century. century. The reporter exemplifies Hegel: the essence of every phenomenon (i.e. the phenomenon of György Marx) is in his own history. „ If you have to, let’s talk about the future ” – will respond positively to the ceremony held at the Academy on the occasion of the release of the Japanese edition of the largest Hungarian scientific bestseller. This is how this birthday non-lifetime interview began … About the future of science – if you like.

Professor György Marx, 75, is registered as a particle astrophysicist by lexicons. Even in his youth, he wrote himself among the much-quoted scientists by inventing the depopulation. Author of university and high school textbooks, educational works and essays. After many domestic and foreign recognitions, he received the Bragg Prize of the English Physical Society last year for his renewed work, and the Nemes-Nagy Ágnes Prize of the National Cultural Fund for his essay writing activities. His biggest book success is the arrival of the Martians, which, in addition to Hungarian, also appeared in English and Japanese editions about the history-shaping Hungarian scientists who gained recognition for their homeland in the West.

– Which is true, true, we left behind an interesting century. But we left it behind. It was interesting because it seemed at first that physicists had nothing to research anymore. After all, Newton was still almost a dogma, after differential and integral calculus allowed us to calculate the future position of the bodies at any later time, knowing the current position and speed of the moving bodies. In other words, knowing the law of force, the course could be calculated for any later time – either a little later or a century later. In chemistry, the elements, the hard atoms, were unchanged. In the XIX. century showed the deterministic ending. The strict equations of movement of rigid bodies and light waves were known exactly. Then a big surprise happened: in the XIX. After the 20th century, a completely different era ensued: the XX. century.

– Who would have thought that relativity would be born. Which is the same as the new era, as Einstein published his first theory of relativity in 1905 and his second theory of relativity in 1916.

– No, I would rather assume that the XIX. Einstein’s theory of relativity was the last great creation of the 19th century: it also inserts space among the variables with a strictly determined destiny, thus crowning the XIX. century classical physics. A XX. The first qualitatively new result of the 20th century is quantum mechanics. Max Planck in his student age, in the XIX. he hesitated in the last years of the 19th century to choose physics as his studio, and his teacher tried to dissuade him, citing the fact that everything in physics had already been invented. But fortunately for Planck and all of us, some obscured corners of science remained. In December 1900, he, Max Planck, reported apologetically at the German Academy in Berlin: the radiation of glowing bodies can only be understood as, that they are very tiny but of a certain amount of energy quantum (energy doses, light balls?) radiate out. The arriving XX. The great physicists of the 19th century: Heisenberg, Dirac and Wigner were born just in the early 19th century and created a beautiful new world in the 1920s. It was a huge era, and its results quickly transformed scientific public thinking. So much so that these new insights were also integrated into education extremely quickly. A II. during World War II – when I went to school – at the Reformed High School on Lónyay Street, the wave nature of the electron and the probability interpretation of these waves were already textbook curricula. I answered that at graduation! When I got to college, my professor Károly Novobátzky, as a young teaching assistant, entrusted me to pay close attention to the new things, to refer to them, because what is new in physics is probably the truth. The only problem was that the XX. century, the ultimate truths alternated.

– Primarily in politics. Revolutions and regime changes followed one another.

– Again, I would focus on something else. For the minds that defined the last century were probably not politicians. They will not be registered in posterity. Not even Gyula Gömbös, not even Eisenhower or Molotov. They won’t even be included in future high school history textbooks. They are forgotten (perhaps forgotten in most places, only our textbooks remember them). But in the next century, János Neumann, who developed the electronically programmable computer, will also be remembered worldwide. Or, for example, Tódor Kármán, who invented the jet plane and launched active space exploration.

– You mention textbooks. I – with many, with others – Professor György Marx as a scholarly teacher, a passionate innovator of education in the 1960s, who in the columns of New Scripture “Aging Time” extremely effective essay. In this writing, he explained how the proliferation of scientific discoveries, the multiplication of information affects the obsolescence of dead knowledge, and how new research processes encourage continuous reforms of school curricula, books, and methods, instead of teaching data, why urgently need to move to creative education that develops thinking.

– Today, with a better knowledge of foreign educational institutions, I see that this innovative intention was no stranger to the traditions and spirituality of the best Hungarian secondary schools. In America, expensive schools, where wealthy parents pay huge sums of money, in return, society expects it to teach with understandable simplicity. The child will grasp it, understand the long-established concepts, and at home do not ask for something that Dad would not be able to answer. The school should promote social integration, in other words, adaptation. In Hungary, however, history was so dense that we had to prepare for the unforeseen future. This unrest has helped generations survive cataclysms. It was a very inspiringly tough world. For example, I was able to get through the torments of military service due to the fact that as a – student, I took on accounting tasks in a military plant, although I did not have accounting skills. Just because I dared flexibly and could think (thanks to my best teachers), I always successfully found the error in the liquidations that the accountants were looking for in vain. My boss also said: I would miss a career if I didn’t go as an accountant, I would have a nice career as an accountant! But I became a physicist. When the password was born in 1957 after the revolution: MUK! (starting again in March), “collected” in a “preventive” way as an instructor classified as “dangerous” at university, to whom students are too keen to listen. Don’t mix “trouble. I was placed in a two-meter cell in the collection prison with my eighth; they were closed with quite a few illustrious personalities: Tibor Liska, the economist, for example, and we all received extremely instructive training at seminars and discussion days in the cell. I held a prison course on nuclear physics, Liska talked about her ideas for economic reform.

– Many of these “universities” worked then. Former cellmates still remember the “closed” courses of Bibo, Göncz, and other knowledgeable “dangerous” intellectuals. In your books on Martians, you explain the well-known world successes of Hungarian science and Hungarian intellectuals in general by saying that ours was a “long-term” country where the frequent conflict situation had to be reckoned with. Politics and the financial world were centrally managed, so the future intelligentsia clung to more objective science and continuous strenuous learning. How do you see that society still has this desire for knowledge, the need to adapt to „ Accelerating Time ”?

– We took Jenő Wigner to a Hungarian school, where she was surprised to find out what exciting questions the children ask in class about science topics. This is the merit of the Hungarian school. The same was stated by Ede Teller when she visited Hungarian grammar school. Openness is the merit of the best Hungarian science teachers. For those who accept the principle that the XIX. instead of the scientific knowledge system completed by the 16th century (which is still a benchmark in official curricula), something should be taught that excites today’s teenagers.

– But there are teachers who believe that complex quantum physical relationships cannot be taught to high school students. And complexity results in failures.

– I am of the opinion and I prove in practice that children have been bored with static knowledge for centuries (s). I tend to move my students out of their composure with a question of what is the simplest basic scientific concept. They cut it to the geometric point. But since something of such an absolutely resting zero extent does not even exist in reality, I answer. Everything we base school geometry on is fiction (which, while offering purposeful relief). János Bolyai, who was born 200 years ago, also said this. There is no more inspiring way to teach than to keep our students mentally excited with shocking questions. If I were the minister, I would introduce a complex matriculation item that could simply be called „ science ”. The separation of disciplines is only a historical heritage, the real world does not know the boundaries separating subjects in a timetable. Researchers are investigating a natural phenomenon, and this is now being done in a complex way at the turn of the millennium, because reality is not a sterile biological, non-chemical, non-astronomic theme. Astronomy is hard to decide today, taught in geography class or physics class. The butterfly grading, spiral training of the last century is now out of date. Now let’s teach about radioactivity, laser, cloning. Let me tell you how to talk and teach about the human genome or the origin of life without the combined use of chemistry, physics, informatics. After all, the basic law of life, the double twist of DNA, was discovered together by a biologist and a physicist, they received the Nobel Prize together for it. And this complex approach must sooner or later be filtered out in the teaching of the natural sciences, or rather the natural sciences. The headings that separate physics and geometry in the timetable are alien and artificial, illogical categories. Where is the limit – I ask in the age of the advancement of biochemistry – between biology and chemistry? I would like to set a timely application topic for teachers: how can one of the most exciting problems of our time, climate change, and within that, the greenhouse effect, atmospheric pollution and the vulnerability of biodiversity, be taught? Let me tell you, who should teach? Biologist? Chemist? Physicist? Geography Teacher? Maybe different? For the first time, I myself chose a chemistry major at university. Then, at the age of three, I went to the astronomy department. Then, when the head of the department was expelled for political reasons (due to his past in American stars), I went to the theoretical physics department. Even today, I like to teach students with different professional pairings, I publish them in physical, astronomical and biological journals. In the 1990s, I strongly advocated setting up a department of biological physics at the university. Fortunately, successfully. I managed to be led by a physicist of exceptional ability and sufficiently complex thinking. As a result, he did not accept the offered American cathedral, but stayed at home and creates here: he accepts Hungarian university students as his co-worker, as they are much more creative than Americans.

– Our conversation started with the excitement of the future. And yet we are mostly exchanging ideas about current problems. Let me ask the stereotypical question, what does György Marx expect in the XXI. century, which has just begun?

– Indeed, the XXI. century excites. I had previously considered how much it determines my destiny that my parents did not value their seventies. Can I enter – e the XXI. century?

– See, given…

– Yes. And it brought surprises that also irritate researchers. New unresolved issues have emerged. For example, as we see more and more of the Universe, we now find that we do not know most of the materials that make up the Universe. „ Quintessence ” and „ dark matter ” – are associated with the Unknown with such aliases. (A century ago, „ ether ” was the unknown existing or non-existent professional alias.) These encourage new solutions, and that requires new thoughts. A good half century ago, I wrote my dissertation on cosmology, and cosmology now moves the imagination of a crowd of people. Then here is the informatics. For now, humanity is barely coping with storing data sets, and they don’t fit in the brain either. My student was Sándor Szalay, son of the professor of atomic physics in Debrecen. He received his doctorate from me. Well, while he was home, he urged the interconnection of university computer systems. But the authorities didn’t pay much attention to his ideas, so he took a job in America, now a professor in Baltimore and there he reached – I think my encouragement also contributed – to the interconnection of giant binoculars and large computer systems. Previously, a terrestrial photo of a picture arriving in the binoculars was taken, viewed by astronomers and computer scanners. Now the information arrives straight into the computer and you can find out from the brightness of the galaxies – after the computer registers – how far the observed celestial bodies are, the slip of the spectral lines can result in their speed. In this way, the Universe can be mapped in three-dimensional space and time. With the IT connection of the giant telescope and the computer, a hundred times as much data is collected each year as astronomers can process. The solution is a supercomputer memory to which this data mass can be transferred, and all countries – even a Hungarian university student – can access it on the Internet. If you have a good idea when you see the data, you can work it out on the latest astronomical data in the world and make your own great discovery. This is the world telescope program. This requires a new idea: in the sea of available data, what is it related to and why. It can be famous at the same time because young and young people can ask the best question.

– But there is also a lot of talk about biology at the beginning of the new century.

– Yes, the great scientific enterprise of the turn of the millennium is HUGO, the human genome program. Automatic machines read what is written in our DNA molecules. There is a solution left: what does this message say? What do the active stages of DNA (genes) say about our body, individuality, inclinations, possibilities? (If we know the content of our own genes, how do we react to the message? And how does society react to the possibility and threat that both the personnel department, the insurance company, the head of office and the police will want to know the turn to him, gene map of a person subordinate to him.) And what does the inactive phase of DNA now say about our human past, our becoming human? Here is how biology, chemistry, physics in our lives are connected to IT, so together they become social sciences. For genetic engineering (cloning?) the XXI. century society, as in the twentieth century. century taught us to live with nuclear energy: not to use it for killing, but to produce clean and cheap electricity, and by tram, we can take the metro when it runs out and oil and gasoline become prohibitively expensive. And this happens in the lives of our children.

– So as science progresses, the original thought becomes really important again.

– This is the secret of the freshness of human thought, and it is beautiful. Many, of course, are scared to think. (How much easier it is to stare at soap operas on TV or find out after 10 minutes who will be the winner in 100 minutes at the end of the action film.) Unraveling the role of consciousness (the subject) by scientific means can become a key issue in scientific thinking. Wigner, for example, was excited as a child about questions about why his dog can’t learn the simple one (and prove this knowledge with building blocks). Why doesn’t the horse understand him when he speaks Hungarian? Why aren’t dogs and horses interested in these human abilities? And perhaps the time is coming when these reactions and feelings of the animal and human worlds may become scientifically processable and systematizable – perhaps measurable –. One day, maybe we’ll understand our souls the same way we do gravity now, Wigner said. But he also had such nightmares that when one gets into great, general comfort because overproduction and advertising lead to the consumer society, he will get bored of thinking. Maybe that’s why a meaningful message doesn’t come from a distance? Maybe that’s why the dog doesn’t count, the horse doesn’t talk because he doesn’t care? On the contrary, I hope.

– Professor Marx’s ideas seem to not only cross the boundaries of individual sciences, but also cross the boundaries of imagination and science. Although, as we know, it has been very deeply preoccupied with civilizations beyond Earth.

– At one time I was also the president of the bioastronomy department of the Astronomical Union. We held a world conference on extraterrestrial intelligence in Balatonfüred. An increasingly extensive movement has been in place for years: SETI (Search of Extraterritorial Intelligence). I’ll tell you how the movement is going now. Radio astronomers will catch a lot of radio signals anyway to understand how stars work. But do these signs also contain an intelligent message from other civilizations? The problem, of course, is how to discover an intelligent message in a cosmic hiss? This is a hanger issue and therefore interesting. Two million people from all over the Earth are now involved in the SETI movement. They read the sea of radio waves caught by astronomical radio telescopes from the Internet and can hunt for intelligent signals. This also shows how many challenges we face in the XXI. century to move our thinking.

– if they receive a divine message? This is conceivable for many. After all, the richer space research, the more natural it is to seek a scientific solution to spiritual issues. The more scientists are asked about this.

– I became a physicist because I am interested in Creation. And that is what will be the fate of the Creation we call the Universe. Which many consider to be of divine origin. But since the Creator is most faithfully testified by the Creation!

– We wish you a long time and thank you for the conversation.

The interview was conducted by N. SÁNDOR LÁSZLÓ

Great catch! So glad to see this.

OT

Nice to see Starships nail biting success !

Just wondering if they could use a material in slots that is responsive to microwaves or induction heating to join the tiles onto the pins. When they wish to remove them they simplly heat them with the same energy source to allow their removal. This idea of bulk payloads into orbit will give us many more options for space infrastructures and move us more towards interstellar probes.

Einstein’s theory of general relativity completely supports Robert Forward’s visionary propulsion paper “Negative Matter Propulsion.” Aliens and ETI might use that technology.

Here is a link to that Forward paper and its abstract:

https://ayuba.fr/pdf/forward1990.pdf

Negative Matter Propulsion

Robert L. Forward*

Forward Unlimited, Malibu, California 90265-7783

Negative matter is a hypothetical form of matter whose active-gravitational, passive-gravitational, inertial,

and rest masses are opposite in sign to normal, positive matter. Negative matter is not antimatter, which as far

as is known has normal (positive) mass. If an object made of negative matter could be obtained and coupled by

elastic, gravitational, or electromagnetic forces to an object containing an equal amount of positive matter, the

interactions between the two objects would result in an unlimited amount of unidirectional acceleration of the

combination without the requirement for an energy source or reaction mass.

In this paper, it is shown in exhaustive detail that, despite their unbelievable propulsive capabilities, negative matter propulsion systems do not violate the Newtonian laws of conservation of linear momentum and energy. Thus, logical objections to the existence of negative matter must be found elsewhere than in Newtonian mechanics. Suggestions are made where evidence for the existence of negative matter might be found.

Negative Mass in Contemporary Physics, and its Application

to Propulsion

Geoffrey A. Landis

https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20190033453/downloads/20190033453.pdf

As first analyzed by Hermann Bondi in 1957, matter with negative mass is consistent with

the structure of Einstein’s general theory of Relativity. Although initially the concept was

considered just a theoretical curiosity, negative mass, or “exotic matter,” is now incorporated

into the body of mainstream physics in a number of forms. Negative mass has a number of

rather non-intuitive properties, which, as first noted by Bondi, and then later commented on

by Forward (1990), Landis (1991), and others, results in possible applications for propulsion

requiring little, or possibly no, expenditure of fuel. As pointed out by Morris and Thorne

(1988) and others, negative mass (or, more strictly, a violation of the null energy condition) is

also a requirement for any proposed faster than light travel. This paper presents the basic

theory of negative mass, the ways by which it can manifest in contemporary physical theory,

and the counterintuitive properties that result, including possible uses for interstellar

propulsion.

Although negative mass has moved from a theoretical curiosity to a concept

fundamental to the contemporary understanding of physics, it is still not clear whether bulk

negative mass can be manufactured, or if it is limited to only appearing at the cosmological

scale (e.g., “dark energy:) or in the quantum (e.g., Casimir vacuum) limit. If it can be

manufactured, the propulsion applications would be significant.

Those are good papers. I’ve read them. Here are two more I’ve read: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Negative_mass https://www.earthtech.org/publications/davis_STAIF_conference_1.pdf

NASA considering an interstellar probe to study the heliosphere, the region of space influenced by the sun

by Sarah A. Spitzer, The Conversation

https://phys.org/news/2024-06-nasa-interstellar-probe-heliosphere-region.html

The initial report here:

https://interstellarprobe.jhuapl.edu/Interstellar-Probe-MCR.pdf

To quote:

NASA is considering developing an interstellar probe. This probe would take measurements of the plasma and magnetic fields in the interstellar medium and image the heliosphere from the outside. To prepare, NASA asked for input from more than 1,000 scientists on a mission concept.

The initial report recommended the probe travel on a trajectory that is about 45 degrees away from the heliosphere’s nose direction. This trajectory would retrace part of Voyager’s path, while reaching some new regions of space. This way, scientists could study new regions and revisit some partly known regions of space.

This path would give the probe only a partly angled view of the heliosphere, and it wouldn’t be able to see the heliotail, the region scientists know the least about.

In the heliotail, scientists predict that the plasma that makes up the heliosphere mixes with the plasma that makes up the interstellar medium. This happens through a process called magnetic reconnection, which allows charged particles to stream from the local interstellar medium into the heliosphere. Just like the neutral particles entering through the nose, these particles affect the space environment within the heliosphere.

In this case, however, the particles have a charge and can interact with solar and planetary magnetic fields. While these interactions occur at the boundaries of the heliosphere, very far from Earth, they affect the makeup of the heliosphere’s interior.

In a new study published in Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences, my colleagues and I evaluated six potential launch directions ranging from the nose to the tail. We found that rather than exiting close to the nose direction, a trajectory intersecting the heliosphere’s flank toward the tail direction would give the best perspective on the heliosphere’s shape.

A trajectory along this direction would present scientists with a unique opportunity to study a completely new region of space within the heliosphere. When the probe exits the heliosphere into interstellar space, it would get a view of the heliosphere from the outside at an angle that would give scientists a more detailed idea of its shape—especially in the disputed tail region.

In the end, whichever direction an interstellar probe launches, the science it returns will be invaluable and quite literally astronomical.