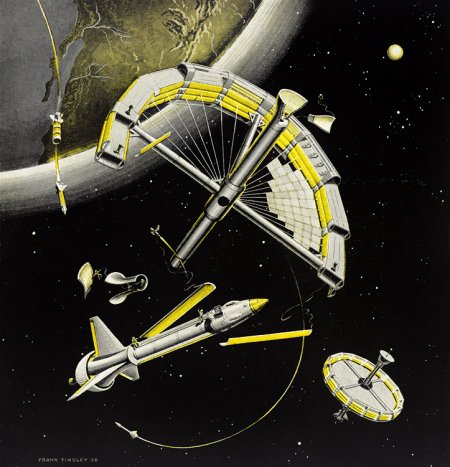

There was a time when images like that of the space station under construction below were standard issue for futurists. It seemed inevitable that after our first tentative orbital flights, we would quickly graduate to building an enormous platform above the Earth, using it as a base for a Moon landing as well as a research establishment in its own right, even a vacation getaway for the well-heeled. It would eventually be part of the supply chain that would create and support a colony on Mars.

The Pastelogram blog featured this futuristic vision by Frank Tinsley recently, done as one of a series of ads that ran in 1958 and 1959 for defense contractor American Bosch Arma. From the ad copy:

New vistas in astronomy will be opened up by such a space station, because of perfect conditions for photography and spectroscopy. It will also provide unique conditions for advanced research in physics, electronics, weather prediction, etc. Three such stations, properly placed, could blanket the entire world with nearly perfect TV transmission. Atomic rocket vehicles with prefabricated skin layers provide building materials for the station, then return to Earth. Similar craft will service an established station, docking by electromagnetic pull exerted from lower section of the station’s axis. Inertial navigation systems will play an increasing role in the exploration of outer space. Arma, now providing such systems for the Air Force Titan and Atlas ICBMs, will be in the vanguard of the race to outer space.

Today, with thoughts of Mir and the International Space Station in our heads, space seems infinitely more constrained. But don’t give up on a future of large space constructs just yet. Watching a Babylon 5 episode last night, I mused that its “two million, five hundred thousand tons of spinning metal, all alone in the night,” though beyond the imagination of current industrial technique, might one day be spawned by nanotechnological methods given suitable raw materials.

Indeed, just as we’ve been adjusting to the idea of nanotechnology as a way to reduce payload sizes for possible interstellar missions, we might go on to think how the same techniques could rejuvenate some older notions. Robert Forward’s lightsail concepts, relying on sails a hundred kilometers in diameter and a Fresnel lens between the orbit of Saturn and Uranus that would have to be as wide as Texas, may start to look a little less dubious. How fast can nano methods, using countless smart assemblers, actually build such a lens to specification?

I have no idea, but as it is the business of the future to surprise us, it seems unwise to rule out such scenarios. Build a Forward-style lens in the outer Solar System and a powerful laser could take a probe to a tenth of lightspeed for a Centauri flyby, or as Forward envisioned, push a manned mission to Epsilon Eridani with return capability. It all comes down to the building of large structures in space, an idea that could be making a nanotech comeback that would gladden the hearts of 1950’s dreamers.

This is the real promise of nanotechnology – not in home replicators that will provide for our most trivial material desires – but in making possible the wildest dreams of mega-engineering that will be, quite frankly, nearly impossible to realize by conventional construction methods.

Great phrase:

it is the business of the future to surprise us

Quite so, though few realize it. Wonderful!

I suspect that “nanotech” used for megaengineering will be quite macroscopic – self-replicating solar-satellite machines are almost a necessity for human interstellar travel considering the power requirements, and I can’t see an SRSSM being a “nanomachine”. But its material processing will almost certainly use nanotech and nano-structured materials will be needed by the square kilometre.

And that’s quite a quote – can I use it for my blog, Paul?

Absolutely, Adam!

I agree with Adam — although nanotech fabrication techniques will no doubt be part of it, the main work of building massive structures in space will probably fall to macroscopic self-replicating robots or “auxons.” Once we have a “work force” that’s automatic, self-sustaining, solar-powered, and able to build itself or anything else from raw materials, the possibilities for megastructure and starship construction, and probably for terraforming as well, become virtually limitless. (Although self-replicating robots carry risks as well, of course; there would still have to be human supervisors making sure they didn’t mutate and run out of control.)

On the note of risks re: self-replicating robots, does anyone know if anyone’s come up with any practical ideas for an “off switch” for nanobots, something that signals all units the equivalent of “Job’s done, stop working”?

^^If we’re talking about nanobots, the analogy for an “off switch” would be the apoptosis of living cells, the genetic “program” that makes them stop replicating and die out eventually. Not a guaranteed solution, though, since sometimes mutation short-circuits apoptosis and cancer results.

Some new old space ad art here:

Agenas in Orbit: 1960

Vast sums of money and vital scientific data ride on the reliability of Bell Aircraft’s rocket engine for Lockheed’s Agena satellite, second stage of the Air Force Discoverer series. The Agena engine, designed with space in mind long before space became a household word, has fulfilled its every mission and placed more tons of useful payload into orbit than any other power plant. This Bell engine now has re-start capability — the first in the nation . . .

From 1960, a quintessentially retro rocket orbiting the Earth in an analogue to the classic atomic-age image of electrons circling a nucleus. Très geek!

http://www.plan59.com/av/av472.htm

Lunar Nuke: 1959

Despite the sky-high transportation costs, Lunar manufacturing should prove economically viable. With unlimited solar power, controlled atmospheres and advanced automation, a considerable commerce could be realized in delicate instruments, rare minerals, reactor cores and other items that might be more efficiently processed or produced in the Moon’s perfect vacuum. To supply the Moon colonists, and to carry their production back to Earth, special rocketships will be developed. Nuclear energy is the most promising source of propellant power. The ship shown here utilizes nuclear fission for heat and hydrogen gas as a working fuel. From pressurized tanks, the gas is fed through a heat exchanger, expanded, and expelled for the motive thrust. When the craft leaves Earth, it carries only enough gas for a one-way trip. For, by extracting hydrogen and oxygen from lunar rocks, Moon settlers could refuel the rocketship for the return voyage. This will permit smaller fuel tanks on the craft and larger payloads. Inertial navigation systems will play an increasing role in the exploration of outer space. Arma, actively supporting the Air Force’s program in long range missiles, is in the vanguard of the race to outer space.

From 1959, another of Frank Tinsley’s monochrome illustrations for American Bosch Arma.

http://www.plan59.com/av/av473.htm

The World of Union Carbide: 1960

This is the world of Union Carbide, bringing you a steady stream of better products from the basic elements of nature. The Periodic Table shown in the illustration lists all the known elements of the world we live in — more than half of them used by Union Carbide . . .

The giant Union Carbide hand in 1960, one of hundreds of hand-themed UC illustrations that ran from 1950 to 1963.

http://www.plan59.com/av/av474.htm

‘Holy Grail’ Of Nanoscience: DNA

Technique Yields 3-D Crystalline

Organization Of Nanoparticles

Science Daily Feb. 6, 2008

*************************

Brookhaven National Laboratory

researchers have for the first time

used DNA to guide the creation of

three-dimensional, ordered,

crystalline structures of

nanoparticles, an achievement some

see as the “holy grail” of

nanoscience. The ability to engineer

such 3-D structures is essential to

producing functional materials that

take advantage of…

http://www.kurzweilai.net/email/newsRedirect.html?newsID=7951&m=25748