Saturn’s moon Iapetus has given us something never before available: A history of its rotation and the effects of that rotation on its development. No other moon in the Solar System is quite like this one, for Iapetus maintains the shape it had when it was only a few hundred million years old. Cassini showed us that shape in a 2005 flyby, revealing a bulge at the moon’s midsection, and a chain of mountains along its equator.

How did the bulge form? The notion, presented in a recent paper published online in Icarus, is that Iapetus’ walnut shape points to a much faster spin rate than we see today and a far warmer interior. The size of the bulge implies a rotation as fast as five hours per revolution, stretching the moon into its current oblate shape. By the time the rotation slowed, the outer shell had frozen and the excess material began to pile up in the mountain chain visible today at the equator.

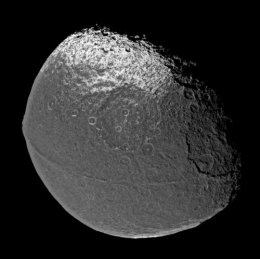

Image: The most unique, and perhaps most remarkable feature discovered on Iapetus in Cassini images is a topographic ridge that coincides almost exactly with the geographic equator. The ridge is conspicuous in the picture as an approximately 20-kilometer wide (12 miles) band that extends from the western (left) side of the disc almost to the day/night boundary on the right. On the left horizon, the peak of the ridge reaches at least 13 kilometers (8 miles) above the surrounding terrain. Along the roughly 1,300 kilometer (800 mile) length over which it can be traced in this picture, it remains almost exactly parallel to the equator within a couple of degrees. Credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute.

“Iapetus’ development literally stopped in its tracks,” says Julie Castillo (JPL). “In order for tidal forces to slow Iapetus to its current spin rate, its interior had to be much warmer, close to the melting point for water ice.” Castillo’s JPL team point to short-lived radioactive isotopes aluminum-26 and iron-60 as the probable cause, and date the moon at 4.564 billion years by studying the aluminum-26 decay rate. The same two isotopes have been found in meteorites formed in the inner Solar System.

Cassini heads for Iapetus again in early September, with a pass 1000 kilometers over the surface. Will new data confirm or challenge this interesting model? Alternative explanations are hard to come by, for the once rapidly rotating Iapetus had to have been warm enough for tidal forces to slow its spin rate to the present period of eighty days. At the same time, its heat source had to be extinguished swiftly for the frozen relic we see today to emerge. September may tell whether the moon that spun fast and froze young has still more secrets to reveal.

Hi Paul

There’s always my alternative explanation – it’s the remains of an equatorial mag-lev ramp used by ETIs some billennia ago. The big “craters” visible on Iapetus are actually quarrying scars.

Tongue-in-cheek but that ridge is so bizarre the new study’s scenario has to be closer to the mark – it’s too weird NOT to have an equally weird explanation. Flash-frozen moons!

Probing the origin of the dark material on Iapetus

Authors: F. Tosi, D. Turrini, A. Coradini, the VIMS Team

(Submitted on 20 Feb 2009)

Abstract: Among the icy satellites of Saturn, Iapetus shows a striking dichotomy between its leading and trailing hemispheres, the former being significantly darker than the latter. Thanks to the VIMS imaging spectrometer onboard Cassini, it is now possible to investigate the spectral features of the satellites in Saturn system within a wider spectral range and with an enhanced accuracy than with the previously available data.

Statistical techniques such as the clustering methods are powerful tools for exploring the spectral data of planetary and satellite surfaces since they allow to identify spectral units between the data of a single celestial body in correlation with the surface geology and to emphasize correlations among the spectra of different bodies.

In this work, we present an application of the \textit{G-mode} method to the VIMS visible and infrared spectra of Phoebe, Iapetus and Hyperion, in order to search for compositional correlations. We also present the results of a dynamical study on the efficiency of Iapetus in capturing putative dust grains travelling inward in Saturn system with the aim of evaluating the viability of Poynting-Robertson drag as the physical mechanism transferring the dark material to the satellite.

The results of spectoscopic classification are used jointly with the ones of the dynamical study to describe a plausible physical scenario for the origin of Iapetus’ dichotomy.

Comments: 15 pages, 7 figures

Subjects: Earth and Planetary Astrophysics (astro-ph.EP)

Cite as: arXiv:0902.3591v1 [astro-ph.EP]

Submission history

From: Diego Turrini [view email]

[v1] Fri, 20 Feb 2009 14:48:12 GMT (1744kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0902.3591

http://antwrp.gsfc.nasa.gov/apod/ap090809.html

Saturn’s Iapetus: Painted Moon

Credit: Cassini Imaging Team, SSI, JPL, ESA, NASA

Explanation: What has happened to Saturn’s moon Iapetus? Vast sections of this strange world are dark as coal, while others are as bright as ice. The composition of the dark material is unknown, but infrared spectra indicate that it possibly contains some dark form of carbon.

Iapetus also has an unusual equatorial ridge that makes it appear like a walnut. To help better understand this seemingly painted moon, NASA directed the robotic Cassini spacecraft orbiting Saturn to swoop within 2,000 kilometers in 2007.

Pictured above, from about 75,000 kilometers out, Cassini’s trajectory allowed unprecedented imaging of the hemisphere of Iapetus that is always trailing. A huge impact crater seen in the south spans a tremendous 450 kilometers and appears superposed on an older crater of similar size.

The dark material is seen increasingly coating the easternmost part of Iapetus, darkening craters and highlands alike. Close inspection indicates that the dark coating typically faces the moon’s equator and is less than a meter thick.

A leading hypothesis is that the dark material is mostly dirt leftover when relatively warm but dirty ice sublimates. An initial coating of dark material may have been effectively painted on by the accretion of meteor-liberated debris from other moons. This and other images from Cassini’s Iapetus flyby are being studied for even greater clues.

Deciphering the Origin of the Regular Satellites of Gaseous Giants – Iapetus: the Rosetta Ice-Moon

Authors: Ignacio Mosqueira, Paul R. Estrada, Sebastien Charnoz

(Submitted on 14 Aug 2009 (v1), last revised 15 Aug 2009 (this version, v2))

Abstract: Here we show that Iapetus can serve to discriminate between satellite formation models. Its accretion history can be understood in terms of a two-component gaseous subnebula, with a relatively dense inner region, and an extended tail out to the location of the irregular satellites, as in the SEMM model of Mosqueira and Estrada (2003a,b).

Following giant planet formation, planetesimals in the feeding zone of Jupiter and Saturn become dynamically excited, and undergo a collisional cascade. Ablation and capture of planetesimal fragments crossing the gaseous circumplanetary disks delivers enough collisional rubble to account for the mass budgets of the regular satellites of Jupiter and Saturn. This process can result in rock/ice fractionation provided the make up of the population of disk crossers is non-homogeneous, thus offering a natural explanation for the marked compositional differences between outer solar nebula objects and those that accreted in the subnebulae of the giant planets.

Consequently, our model leads to an enhancement of the ice content of Iapetus, and to a lesser degree those of Ganymede, Titan and Callisto, and accounts for the (non-stochastic) compositions of these large, low-porosity outer regular satellites of Jupiter and Saturn. (abridged)

Comments: 31 pages, 7 figures, 2 tables, submitted to Icarus

Subjects: Earth and Planetary Astrophysics (astro-ph.EP)

Cite as: arXiv:0908.2112v2 [astro-ph.EP]

Submission history

From: Paul Estrada [view email]

[v1] Fri, 14 Aug 2009 18:33:59 GMT (117kb)

[v2] Sat, 15 Aug 2009 20:48:06 GMT (117kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0908.2112

Dec. 10, 2009

Saturnian satellite Iapetus is coated with foreign dust

By Anne Ju

Iapetus is often called Saturn’s most bizarre moon, due to its starkly contrasting hemispheres — one black as coal, the other white as snow.

Images taken by the Cassini-Huygens spacecraft, orbiting Saturn since 2004, offer the most compelling evidence to date of why and how the moon got its yin-yang appearance, as well as clues to how other such satellites might have formed in the early universe. Analyzed by a research team that includes Cornell scientists, the images are detailed in the Dec. 10 online edition of the journal Science.

“This is not the most fundamental problem in the world,” said research team member Joseph A. Burns, Cornell’s Irving Porter Church Professor of Engineering and professor of astronomy. “But it’s an enigma that’s been puzzling astronomers for centuries.”

Full article here:

http://www.news.cornell.edu/stories/Dec09/CassiniIapetus.html