The accepted take on the formation of Saturn’s rings not so long ago was that they had emerged within the past 100 million years. The most likely driver: A comet that broke a larger moon into pieces, forming ring features seemingly consistent with what the Voyagers saw in the 1970s and the Hubble telescope has seen ever since. But leave it to Cassini to stir things up yet again with much more precise data suggesting that the rings did not form in a cataclysmic event but are continually recycled.

Thus Larry Esposito (Colarado University, Boulder), who is also principal investigator for Cassini’s Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrograph:

“The evidence is consistent with the picture that Saturn has had rings all through its history. We see extensive, rapid recycling of ring material, in which moons are continually shattered into ring particles, which then gather together and re-form moons.”

The findings received less media attention than Voyager 2’s crossing of the termination shock, discussed at the same American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco recently. But they’re interesting nonetheless. Because what Cassini is telling us is that Saturn’s ring system is probably a good deal larger than previously understood, which would explain why the rings aren’t darker. Incoming meteoric dust, it was once thought, should cause such a darkening, but the rings clearly appear bright when seen from Earth and, obviously, from Cassini.

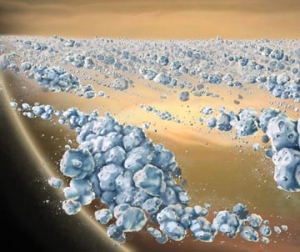

Image: An artist concept of a close-up view of Saturn’s ring particles. The blue particles are composed mostly of ice and clump together to form elongated, curved aggregates, continually forming and dispersing. The space between the clumps is mostly empty. The largest individual particles shown are a few yards across. Image courtesy NASA/JPL/University of Colorado.

“The more mass there is in the rings, the more raw material there is for recycling, which essentially spreads this cosmic pollution around,” says Esposito. “If this pollution is being shared by a much larger volume of ring material, it becomes diluted and helps explain why the rings appear brighter and more pristine than we would have expected.”

We’ll get details in Esposito’s upcoming paper in Icarus. Clumps of icy debris form and break apart with regularity, as observed by Esposito’s team using stellar occultation, examining the rings’ effect on starlight passing through them. A far more ancient structure than once thought, then, but the whole system is also in a continuous state of change as these processes churn on across their vast expanse. A video animation of Saturn’s F-ring undergoing these changes can be viewed here.

If the ring system is old and has survived for billions of years, it makes it more likely that some of the various exoplanets currently known have ring systems. Such ring systems could be detected in transit searches – the frequency of exoplanetary ring systems as a function of the age of their solar systems could give us a better handle on ring lifetimes.

Hi All

The dilution of darkening materials because of the greater ring volume also explains the near invisibility of the other solar planet ring systems – they’re all too thin. Saturn’s system might be unusually heavy, thus a “unique” feature after all. If we don’t see any via transit observations then Saturn will stand out from the crowd.

Saturn Forms by Core Accretion in 3.4 Myr

Authors: Sarah E. Dodson-Robinson (1), Peter Bodenheimer (2), Gregory Laughlin (2), Karen Willacy (3), Neal J. Turner (3), C. A. Beichman (1) ((1) NASA Exoplanet Science Institute, (2) UCO/Lick Observatory, (3) JPL)

(Submitted on 1 Oct 2008)

Abstract: We present two new in situ core accretion simulations of Saturn with planet formation timescales of 3.37 Myr (model S0) and 3.48 Myr (model S1), consistent with observed protostellar disk lifetimes.

In model S0, we assume rapid grain settling reduces opacity due to grains from full interstellar values (Podolak 2003). In model S1, we do not invoke grain settling, instead assigning full interstellar opacities to grains in the envelope.

Surprisingly, the two models produce nearly identical formation timescales and core/atmosphere mass ratios. We therefore observe a new manifestation of core accretion theory: at large heliocentric distances, the solid core growth rate (limited by Keplerian orbital velocity) controls the planet formation timescale. We argue that this paradigm should apply to Uranus and Neptune as well.

Comments: 4 pages, including 1 figure, submitted to ApJ Letters

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0810.0288v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Sarah Dodson-Robinson [view email]

[v1] Wed, 1 Oct 2008 20:59:18 GMT (26kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0810.0288

Did Saturn’s rings form during the Late Heavy Bombardment ?

Authors: Sebastien Charnoz, Alessandro Morbidelli, Luke H. Dones, Julien Salmon

(Submitted on 29 Sep 2008)

Abstract: The origin of Saturn\’ s massive ring system is still unknown. Two popular scenarios – the tidal splitting of passing comets and the collisional destruction of a satellite – rely on a high cometary flux in the past. In the present paper we attempt to quantify the cometary flux during the Late Heavy Bombardment (LHB) to assess the likelihood of both scenarios. Our analysis relies on the so-called Nice model of the origin of the LHB (Tsiganis et al., 2005; Morbidelli et al., 2005; Gomes et al., 2005) and on the size distribution of the primordial trans-Neptunian planetesimals constrained in Charnoz & Morbidelli (2007).

We find that the cometary flux on Saturn during the LHB was so high that both scenarios for the formation of Saturn rings are viable in principle. However, a more detailed study shows that the comet tidal disruption scenario implies that all four giant planets should have comparable ring systems whereas the destroyed satellite scenario would work only for Saturn, and perhaps Jupiter. This is because in Saturn\’s system, the synchronous orbit is interior to the Roche Limit, which is a necessary condition for maintaining a satellite in the Roche zone up to the time of the LHB. We also discuss the apparent elimination of silicates from the ring parent body implied by the purity of the ice in Saturn \’ s rings.

The LHB has also strong implications for the survival of the Saturnian satellites: all satellites smaller than Mimas would have been destroyed during the LHB, whereas Enceladus would have had from 40% to 70% chance of survival depending on the disruption model. In conclusion, these results suggest that the LHB is the sweet moment for the formation of a massive ring system around Saturn.

Comments: 39 pages, 9 figures, 3 tables. Accepted for publication (with minor modifications) in ICARUS

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0809.5073v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Sebastien Charnoz [view email]

[v1] Mon, 29 Sep 2008 21:07:24 GMT (307kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0809.5073

Synchronization mechanism of sharp edges in rings of Saturn

Authors: D. L. Shepelyansky, A. S. Pikovsky, J. Schmidt, F. Spahn

(Submitted on 23 Dec 2008)

Abstract: We propose a new mechanism which explains the existence of enormously sharp edges in the rings of Saturn. This mechanism is based on the synchronization phenomenon due to which the epicycle rotational phases of particles in the ring, under certain conditions, become synchronized with the phase of external satellite, e.g. with the phase of Mimas in the case of the outer B ring edge.

This synchronization eliminates collisions between particles and suppress the diffusion induced by collisions by orders of magnitude. The minimum of the diffusion is reached at the center of the synchronization regime corresponding to the ratio 2:1 between the orbital frequency at the edge of B ring and the orbital frequency of Mimas. The synchronization theory gives the sharpness of the edge in few tens of meters that is in agreement with available observations.

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph); Statistical Mechanics (cond-mat.stat-mech); Pattern Formation and Solitons (nlin.PS)

Cite as: arXiv:0812.4372v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Arkady Pikovsky [view email]

[v1] Tue, 23 Dec 2008 11:31:08 GMT (1684kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0812.4372