Given the budgetary situation, it’s nice to know we can still get to the outer Solar System without the cost of a flagship-class mission like Cassini, which weighed in at 3.26 billion — that included $1.4 billion for pre-launch development, $704 million for mission operations, $54 million for tracking and $422 million for the launch vehicle. Now Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (JHU/APL) is moving forward on a much cheaper mission concept to reach Titan, one of the three proposals selected as candidates for an upcoming NASA Discovery Program mission.

We’re now down to three proposals for this mission out of an original 28 submitted last summer, with each team receiving $3 million to develop a still more detailed concept study. The Titan mission is just what the doctor ordered to perk up your ailing sense of wonder, intended to deliver a capsule called Titan Mare Explorer (TiME) that would land in and explore one of the large seas that Cassini has helped us map. The concept is clearly workable, and it will be cost-capped at $425 million, although this doesn’t cover the funding for the launch vehicle.

Remember that the NEAR mission, the first to orbit and land on an asteroid, was a JHU/APL creation — this was the first of the Discovery-class missions — and so is MESSENGER, now in orbit around Mercury since March. I’ve mentioned many times in these pages my interest in the Innovative Interstellar Explorer concept that has been developed there over the years in the hands of Ralph McNutt, with original work done through Phase I and II grants from NASA’s Institute for Advanced Concepts. And I certainly don’t want to forget the ongoing flight of New Horizons, designed and built at JHU/APL and tallying mission costs in the range of $700 million.

But I don’t want to focus solely on money here, because the Titan Mare Explorer, if chosen for flight, is the sort of breathtaking mission we’ve been hoping to see delivered to Titan, a robotic boat that would be parachuted into Ligeia Mare, the second largest of Titan’s northern seas, for a 96-day mission, measuring the moon’s organic molecules and analyzing its chemistry, not to mention producing images of sea and sky on Titan that would surely be unforgetable. The plan is to launch between 2016 and 2018 to arrive before winter sets in at the moon’s north pole.

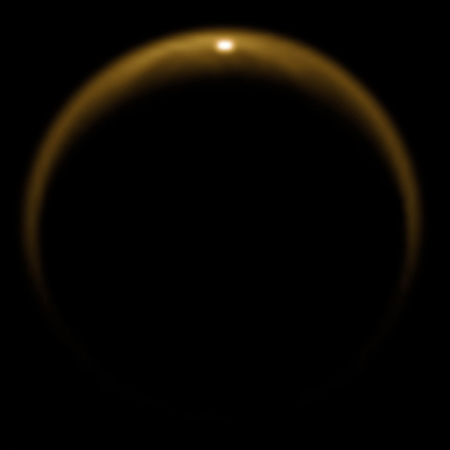

Image: Sunlight reflects off a Titan lake in this image captured by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft. The Titan Mare Explorer (TiME), a candidate for NASA’s next Discovery-class mission, would perform the first direct inspection of an ocean environment beyond Earth by landing in, and floating on, a large methane-ethane sea on the cloudy, complex moon of Saturn. Credit: NASA.

Here I want to quote TiME project lead scientist Ellen Stofan (Proxemy Research Gaithersburg, MD), who was recently interviewed by Ian O’Neill for Discovery News:

“Titan is often referred to as a pre-biotic world. It actually has all the sort of building block chemicals that were present on Earth when life evolved. The idea for Titan is that with those very, very cold temperatures and with water being frozen solid, could life actually develop, or is it just too cold so those chemical reactions just can’t get going?”

The two other Discovery Program possibilities are a mission to study the Martian interior (Geophysical Monitoring Station) and a cometary lander (Comet Hopper). We’ll have another review of all three studies in 2012, after which NASA will select the winner. In the meantime, it’s also interesting to see three proposals selected for technology development — this means selected teams will receive funding to bring their technologies to a higher readiness level. All three of these are interesting in their own right for long-term development:

- Whipple would use a technique called blind occultation to monitor tens of thousands of stars for signs of outer system objects, helping us inventory icy chunks at the system’s edge.

- NEOCam would study Near-Earth Objects through a new telescope designed for infrared measurements that help us understand small bodies crossing the Earth’s orbit.

- Primitive Material Explorer (PriME) would use a mass spectrometer to measure the chemical composition of a comet and explore the role of comets in delivering volatiles to Earth.

Wouldn’t it be a good idea to build the vessel entirely in space, to minimize the chances of microorganisms hitching a ride?

There was an attempt to justify the Enterprise being constructed on the ground in the latest Star Trek movie. I wonder how plausible you thought that was?

As worthy as the other two missions might be, the Titan Mare Explorer is clearly the most innovative, and has the greatest possibility for fundamental impact. Sure, the internal geology of Mars and the nature of comets is interesting, but this is a frickin’ boat on an extraterrestrial methane sea! It is really hard to get cooler than that, and the potential science value would be tremendous.

Didn’t Chris McKay speculate that there might even be biotic processes on Titan based on the chemical profile of the atmosphere near the ground?

A landing on Titan would certainly be a very interesting mission. Color images/video of the surface could indeed inspire imaginations and offer the first world with a surface that isn’t cratered regolith, with an ocean that might seem vibrant with waves.

Speaking of which, where are the space artists depicting the surfaces of the newly discovered extrasolar worlds? The last thread with talk of a Neptune sized world with an ocean and H2 atmosphere would seem to be an excellent subject.

While I would definitely like to see this mission become a reality, I’m not entirely convinced it will be selected due to the risks involved. For starters, it appears that Titan’s lakes are seasonal and I can certainly see the argument about whether we know how likely it is that the lake in question is going to be there when the probe arrives, and the feasibility of choosing an alternative landing site if it isn’t.

Alex: some artistic impressions of newly discovered extrasolar worlds:

http://www.hardyart.demon.co.uk/pages-gallery/p-extra1.html

This one is of a purely imaginary planet, but it does have a lake:

http://www.hawkwindmuseum.co.uk/images/Hardy%20Proxima3.jpg

And here (scroll down) are two surface images of Earth-like exoplanets:

http://www.hardyart.demon.co.uk/pages-gallery/p-extra2.html

Both with lakes, although I think the imaginary Proxima planet looked better.

Stephen

Oxford, UK

Andy, there’s no doubt that some of the lakes seen are seasonal, but the big northern mares are substantial – even if their shorelines expand and contract considerably with the seasons its unlikely that they disappear!

Land in the deep….water….errr hydrocarbon and take it from there. Oh for the thing to last long enough for some Titanian zephyr, tide or current to push it into sign of a shoreline!

P

I hope it has a James Cameron HD 3D camera.

I’m struggling to see the scientific value; Finding some form of life? I think is incredibly unlikely, reconnaissance for sending people there? No time soon, discovering useful resources? incredibly unlikely, getting useful insights into chemistry? Doubtful.

All that’s left is: “wow, imagine, some photos from a methane sea!”

The complex chemistry of these seas would surely offer a great return in terms of pure science, and the location, pictures and extraterrestrial weather reports, would offer a very high return in terms of public perception of science and its power to bring us to a positive destiny. Lets not do it because of the science, lets do it to bring the world a hope in its future that it has not felt since the days of Apollo.

stephen said on May 11, 2011 at 8:40:

“Wouldn’t it be a good idea to build the vessel entirely in space, to minimize the chances of microorganisms hitching a ride?

“There was an attempt to justify the Enterprise being constructed on the ground in the latest Star Trek movie. I wonder how plausible you thought that was?”

Yes, we could build the Titan Lake Boat in space, but it would add incredible expense, delay the mission by a decade or more, plus it would still be built at this point by humans who would need an entire new facility for this, thus more money, more resources, and the humans would contribute microbes just the same.

Not quite sure of the Star Trek – Enterprise connection here, except that in the last ST film they used Titan’s thick atmosphere to hide the starship from the bad guys.

As for constructing the Enterprise on Earth’s surface, that did not make practical sense; it was obviously done for the appearing cool factor. In addition, that nearby canyon which the young James T. Kirk plunged the antique car into was apparently made by the folks building the starship, digging up the local Iowa resources for material! I guess the EPA is defunct by the 23rd Century.

Andrew W – Here, from (a possibly older iteration of) the proposal, are the mission science objectives, in priority order;

Science Objective 1. Determine the chemistry of seas to constrain Titan’s methane cycle, look for patterns in the abundance of constituents in the liquids and analyze noble gases. Instruments: Mass Spectrometer (MS), Meteorology and Physical Properties Package (MP3).

•

Science Objective 2. Determine the depth of the Titan sea to determine sea volumes, and thus, organic inventory.

Instrument: Meteorology and Physical Properties Package (Sonar) (MP3).

•

Science Objective 3. Constrain lacustrine processes on Titan by characterizing physical properties of sea liquids and how they vary with depth. Instrument: Meteorology and Physical Properties Package (MP3).

•

Science Objective 4. Determine how the local meteorology over the seas ties to the global cycling of methane on seasonal and longer timescales. Instrument: Meteorology and Physical Properties Package (MP3).

•

Science Objective 5. Analyze the nature of the sea surface and if possible, shorelines, to constrain physical properties of sea liquids and better understand origin, evolution, and subsurface methane/ethane hydrology of Titan lakes and seas. Instrument: Descent and Surface Imagers (DI, SI).

(Disclaimer: I work for APL am hoping to be here when TiME sends home the first images of the methane sharks.)

There are good links from Wikipedia’s Titan page to papers discussing the organic chemistry on Titan and the methanologic cycle. A big question is how does the methane in the atmosphere get replenished, and parallel to that, what is consuming acetylene and molecular hydrogen. Experiments, similar to Urey-Miller but starting with materials appropriate to Titan, have produced nucleotide bases, amino acids, and other interesting chemistry.

So, there’s plenty that could be learned from a visit to Titan’s seas. Whether this mission answers all or some of those questions, whether it is even chosen to make the attempt, remains to be seen.

Chris, even above I feel that you undersell this mission. Although all of those priorities listed are very good, they are all associated directly with Titan.

How about the chemical package being more about studying the mix with an eye to its prebiotic implications. This natural laboratory might be our best clue yet as to how life on Earth started, and if answering the question “where do we come from” is not a priority what is?

Building the probe in space would provide jobs, and maybe it wouldn’t be any more expensive than some of the other things governments and billionaires are doing…(let’s not go there.)

It would delay the mission, but what’s your hurry? We’re all anxious to find out more, but it’ll still be there, I’m sure. And didn’t we want to expand the International Space Station anyway?

How much would the risk of microbes, insects and atmospheric pollutants be decreased if we build it in space?

Alan Dean Foster’s novelization of the Star Trek movie offered some rationales for building it on the ground…but that was for a manned vessel with artificial gravity, so maybe it’s not really relevant. Oh, well. Thanks.

Telse wrote “. . . Sure, the internal geology of Mars and the nature of comets is interesting, but this is a frickin’ boat on an extraterrestrial methane sea! It is really hard to get cooler than that, and the potential science value would be tremendous.”

I agree. The only thing cooler is if the boat, after splashdown, released a small, (yet live) shark with a frickin’ laser beam attached to it’s head while the whole operation was video recorded and beamed back!

Martin J Sallberg, the surface chemistry of Titan might be deficient in acetylene and hydrogen, yet to me that is not the exciting part. True, it seems nearly miraculous that such a specific catalyst could operate so efficiently at the surface temperature here, but the real problem is that this surface seems depleted in EVERY major potential food metabolite.

You also brought an issue that should preclude life in liquid methane – there can be no DNA. Of cause, you could use a different genetic material, but it is the very problem of having a charged ‘backbone’ that makes it possible to retain information with high replicative fidelity that also makes it impossible to be soluble in a nonpolar solvent.

Perhaps then your exotic eukaryote origin hypothesis should include the hypothesised existence of a eutectic mix of water and another chemical (perhaps ammonia) near Titans surface?

AVIATR: An Airplane Mission for Titan

by Lillian Ortiz on January 2, 2012

It has been said that the atmosphere on Titan is so dense that a person could strap a pair of wings on their back and soar through its skies.

It’s a pretty fascinating thought. And Titan – Saturn’s largest moon – is a pretty fascinating place. After all, it’s the only other body in our solar system (besides Earth, of course) that has that type of atmosphere and evidence of liquid on its surface.

“As far as its scientific interest, Titan is the most interesting target in the Solar System,” Dr. Jason W. Barnes of the University of Idaho told Universe Today.

That’s why Barnes and a team of 30 scientists and engineers created an unmanned mission concept to explore Titan called AVIATR (Aerial Vehicle for In-situ and Airborne Titan Reconnaissance). The plan, which primarily consists of a 120 kg plane soaring through the natural satellite’s atmosphere, was published online late last month.

The goal of the plane concept – which according to Barnes can serve as a standalone mission or as part of a larger Titan-focused exploration program – is to study the moon’s geography (its mountains, dunes, lakes and seas), as well as its atmosphere (the wind, haze, clouds and rain. Did you know that Titan is the only other place is our solar system where it rains?)

AVIATR is composed of three vehicles: one for space travel, one for entry and descent into Titan, and a plane to fly through the atmosphere. AVIATR, estimated to cost $715 million, would not prevent other missions from occurring on Titan, Barnes said. Instead, it would supplement the science being done by other projects.

“The science that AVIATR could do complements the science that can be accomplished from both orbiting and landed platforms,” the article stated.

Unfortunately, it seems like the plane concept won’t be happening anytime soon.

Full article, including a poster, here:

http://www.universetoday.com/92286/aviatr-an-airplane-mission-for-titan/

Here is the paper in HTML form:

http://www.springerlink.com/content/76117941970t5291/fulltext.html

Smooth Sailing on Titan

Lakes on Saturn’s moon Titan don’t do the wave very well.

by Camille Carlisle

Radar images from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft show glassy smooth surfaces, even on bodies like Ligeia Mare, a large sea roughly 400 kilometers (250 miles) wide. There are patterns on the shoreline of the southern hemisphere’s Ontario Lacus that might be from waves, but the features aren’t definitive.

Winds haven’t been too high on Titan since Cassini first arrived in Saturn’s system in 2004, so the lack of waves is odd but understandable.

The ESA’s Huygens probe sent back amazing surface images, including snapshots of delta-looking features, when it made its dent in the moon’s equatorial region in January 2005. But it’s hard to study a lake when you land in a sand dune. Scientists hope to send another mission, called the Titan Mare Explorer (TiME), to make its splat in Ligeia Mare in 2023 — if NASA chooses it from one of three potential Discovery missions up for selection this year.

An upcoming Icarus paper by TiME researchers Ralph Lorenz (Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory) and Alexander Hayes (University of California, Berkeley) confirms that the capsule shouldn’t face fearsome seas if it survives the funding and launch gauntlet. The duo calculated how various parameters — air density and liquid’s resistance to flow, among others — affect wave growth, given the moon’s weak surface winds. They found that waves on Ligeia Mare won’t normally exceed 0.2 meters (not even a foot high), and occasionally might reach just over a half meter in the course of a few months.

“You’d notice 0.2-meter waves if you were in a rowboat, but they wouldn’t get surfers excited,” Lorenz says.

Full article here:

http://www.skyandtelescope.com/news/home/Calm-Sailing-on-Titan-142675475.html